Maaretta Jaukkuri: With Curiosity as a Curatorial Guideline

An interview with Maaretta Jaukkuri by Power Ekroth and Marita Muukkonen

Images from Maaretta Jaukkuri’s personal photo archive

Internationally renowned curator, professor, and writer Maaretta Jaukkuri has worked for institutions, such as the Nordic Art Center and Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma as well as been an independent curator since the late 60s. In these positions she has always advocated for artists’ freedom and emphasizes a current concern for using or instrumentalizing art: “I think artists' freedom is the most important inheritance that we have, and if we lose it, everything changes. I am however a bit worried today about the fact that art is considered to “save the world” and stop climate change and the likes, because saving the world requires that we all as citizens change and in doing it change the society. The only thing we can do with art is to help those who want to save the world. I'm worried that art is being used in a way that endangers its freedom.”

Marita Muukkonen (MM): With Maaretta there is a long journey, so where to start?

Power Ekroth (PE): How come you became a curator, and what were your interests from the start?

Maaretta Jaukkuri (MJ): I started working with exhibitions once I got my Master’s degree from the University in Helsinki. My main interest has always been contemporary art. This was in the late 60s and, of course, it was a totally different time. There were so few jobs within the sector that I decided to major first in English philology but completed my Art History degree later.

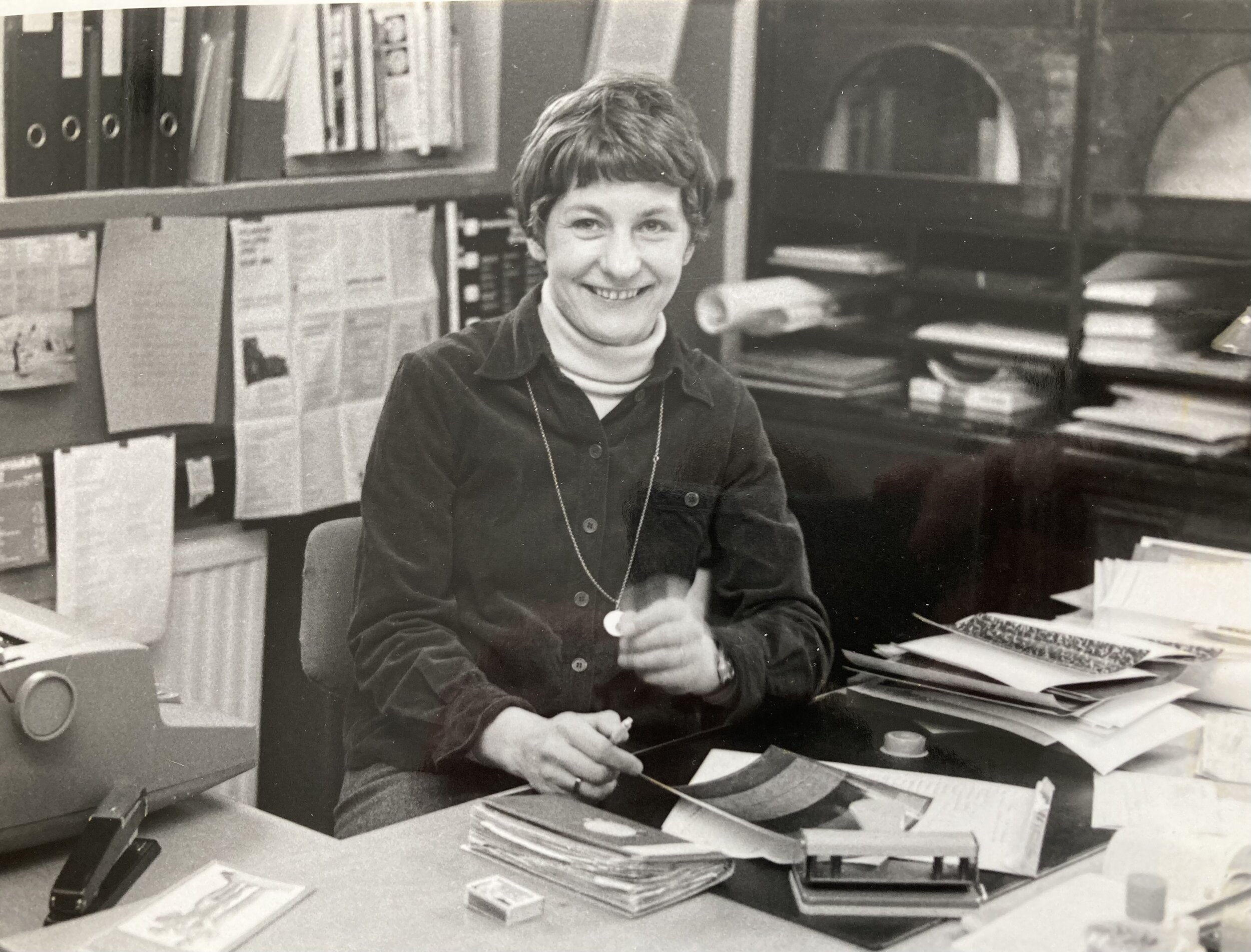

Maaretta Jaukkuri in the office of the Artists' Association in the 70s

My first job was as secretary at the Association of Finnish Sculptors, then as the exhibitions and information secretary at the Artists’ Association of Finland and the secretary of the Finnish section of the Nordiska Konstförbundet (Nordic Art Association). The concept of the curator as we now understand it was not known back then. The people in charge of the exhibitions had the title of commissionaires. I was an administrator. I stayed in this position over a decade, and in 1982 I started at the Nordic Arts Centre in Suomenlinna/Sveaborg. First, I was appointed as the exhibitions secretary there as well, but then the title was later changed to head of exhibitions. I was always in charge of exhibitions, the work was the same from the beginning. In the 80s, the concept of curator started to emerge, slowly gaining ground also in the Nordic countries.

Nina Roos, Kari Cavén, technicians, Maaretta Jaukkuri and Björn Ransve installing Ransve’s exhibition in the Jetty Barrack Gallery, Nordic Art Centre at Suomenlinna 1985.

MM: What was the importance of the Nordic Arts Centre for you and what did working there mean to you professionally?

MJ: It was of huge importance to me. The 80s was a very Nordic period; there were a lot of Nordic exhibitions happening as well as many forms of Nordic collaborations. Economies were booming and it was a very optimistic time and it seemed like many things were possible. The Centre, however, had a relatively small exhibitions budget. We really worked hard as a staff of only two people and a technician and made a year-round program in the Jetty Barracks Gallery as well as touring exhibitions in the Nordic countries. I learned a lot and I enjoyed it. We had quite free hands. The Nordic cooperation normally works very well. I don’t know if this is because of the cultural similarities, but, at least, the Nordic societies are quite similar in social and economic structures. It was a bit tedious to have the continuous discussion about the so-called ”Nordic-ness” that doesn’t really exist. I remember answering that “OK, if we can’t use the construction ”Nordic”, then maybe it is also a bit suspect to have these national institutions of “Finnish”/“Swedish” and so on. In a way they are all constructs which we today understand a bit better than at that time.

MJ: The congress of the IAA (International Association of Art) 1982 was arranged jointly with all the Nordic IAA sections. Simultaneously a congress of AICA (International Association of Art Crtics) took place in Helsinki as well. The participants of both the congresses visited the Nordic Arts Centre on Sveaborg. I am in the picture with Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, The person to the right is Jaakko Lintinen the then editor of Taide magazine. A couple of days after the congress I started working at the Nordic Arts Centre 1982.

MM: The Nordic cooperation was re-organized, NIFCA (Nordic Institute for Contemporary Art), was founded in 1997 after the Nordic Arts Centre was shut down in 1996. You were also a member of the board of NIFCA later on. NIFCA was closed down eventually in 2006. What do you think now in retrospect; do you think something was lost when NIFCA was closed down? During the time of NIFCA, it was functioning more internationally, is there something we lost in the region and internationally when it disappeared?

MJ: When I was working at the Nordic Arts Centre, we were not allowed to exhibit artists from other countries than the Nordic ones, but there were various ways we could expand that a little. One of the things was to invite Dieter Roth who has been living in Iceland to curate an exhibition with Icelandic artists. In this way, we could show his work. Slowly it started to open up a bit. We also showed the German artist Raffael Rheinsberg and the Japanese sculptor Toshikatsu Endo.

NIFCA did fantastic work, first with Anders Kreuger as director, and the international seminar 1998 “Stopping the Process?” for curators in the Lofoten Islands, in the organization of which I was involved. Then, when Søren Friis Møller took over as director, he expanded the idea of the role of residencies as well as the ideas on how to really bring Nordic artists and ideas into an international context. Søren also hired three part-time curators, one from the UK, one from France and one from Finland. This openness and ability to initiate discussions is what I think has been lost. It has, of course, been compensated by more international orientation in all the five countries, but the joint Nordic initiatives are missing. The Nordic arts magazine is also history. [first Siksi, later NU, The Nordic Art Review]. I was partly guilty of it being closed down in 2002 as I together with Søren was NIFCA’s representative on the board of the magazine. Søren was really critical, and there were a lot of tensions in the organization when it ended. Maybe it could have been saved in some way, and maybe it would have ended by itself after a couple of years anyway when NIFCA was closed down, but we now miss a magazine – a forum for information and discussion. I am naturally aware that Kunstkritikk is Scandinavian and also informs about Iceland and Finland. I also miss regular Nordic exhibitions.

We are all small countries, so we easily tend to develop certain kinds of national agendas and hierarchies concerning who are “the best artists.” With exhibitions with other views as well as the magazine for discussions, it was possible to even ever so slightly ”disturb” these kinds of hierarchies by bringing other people and other viewpoints into the spotlight. This was also often met with irritation.

PE: What was the major criticism of the magazine about?

MJ: At first, it was moved from Finland to Sweden on a little bit of unclear premises. I was not involved in NIFCA’s activities at the time, so I don’t know this situation well. Then it seemed that a few people made the magazine into their own personal project, and they wouldn’t allow the type of normal staff changes while also blocking other, new ideas. It became a sort of fixed, closed system, and too much identified with a few people. It was also criticized on the basis of various, even totally opposing ideas among artists at that time. But in retrospect I think it was a mistake to shut it down, we should have discussed things more calmly.

MM: With NIFCA, at least, I personally experienced that it also functioned as a platform for younger Nordic curators with residencies and possibilities to curate projects. Did you see it as a platform for curating? How did your own curatorship and your networks develop in the Nordic context?

MJ: Yes, the young curators had a forum both at the Nordic Arts Centre and even more so during the NIFCA period. While I worked there, we also started a biennial for younger artists and curators of the same generation. It was called Aurora to partner with the older and more established Nordic biennale Borealis. I think all those events functioned very well, when young artists and curators could meet and work together in a professional setting with an institution and a structure to support them. There may be a lot of things an institution can’t provide, but I have a feeling that it must feel comfortable to have a budget, technicians and staff who can help you so that you can concentrate on your work and role.

MJ: Hulda Hákon's mini relief (10,8x11,2 cm) mentioning all the artists participating in the Borealis 3 exhibition at Malmö Konsthall 1987, as well as the curators Björn Springfeldt and myself.

What the Arts Centre meant to me is that it made me into a curator. I got more and more interested in all the issues related to exhibitions, like themes, installations, organizations, as well as the different roles in the whole process. I was also fortunate to meet and work with many interesting people, some of them are still colleagues and friends. It was not such a huge change from what I had been doing earlier, so I knew somehow the protocols and routines of exhibition making. I’m very happy I had the kind of background in practical exhibition work that I had. It gave me a lot of confidence in believing you can make an exhibition and how to work with artists. I’m very glad I didn’t come straight from university, and instead had a background in organizing and administering, and had been involved in exhibition exchanges with other countries.

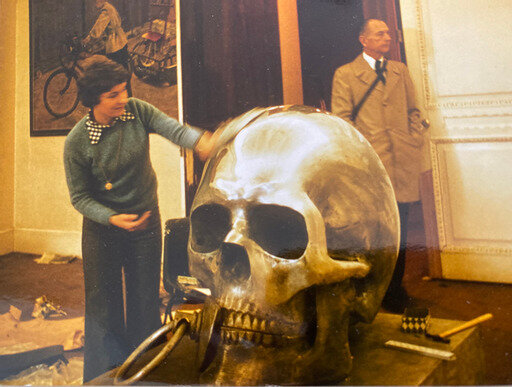

Workaday Finland exhibition at ICA in London in 1974. Jaukkuri is polishing the sculpture made by Arvi Siikamäki.

You asked me earlier about what changed when I became curator. What changed was that I could plan a program, transform ideas into exhibitions, and invite artists whose work was interesting both in general terms but also in a given context. As curator, my work became so much more demanding, challenging, and rewarding but there was also a different kind of responsibility both towards the artists, the public, and the institution. I had always liked to follow what is going on in art, but now it was a crucial part of my job.

PE: There was a certain time when the idea of what a curator was changed from being the type of ”objective” administrator and sort of came out of the walls and turned subjective and actually said something with an individual voice. I wanted to know more about your experience and your take on this?

MJ: I think that a voice develops slowly. A voice, if I understand it correctly, means that you have a personal way of working and making selections. I never thought of myself as having a voice in any specific way. Times change and according to one’s interests, one simply learns more. I have also experienced that if I get a bit uncertain, perhaps even a bit irritated while looking at something, I must become really observant because these moments have a potentiality to turn into long-time interests. But well, yes, my work can have an influence. I don’t know if anyone can recognize that I have curated an exhibition. In the course of years of working with contemporary art, one slowly starts to see the wider framework more clearly as well as the dynamics of the situation. Still, it is important to trust what you think is important to show it while also being aware of where something is shown and when.

MJ: Staffan Cullberg curated a touring Nordic exhibition titled Öga mot Öga in 1976/77. It was the first Nordic exhibition as far as I know with a curator in the present sense of the term. Staffan is here pictured while presenting the exhibition. It was arranged by Nordiska Konstförbundet (NKF).

PE: And what were your particular interests, you said to yourself that you were representing the Nordic, and that is a construction of course, but did you have any interest within it that was sort of your passion.

MJ: I am interested in many kinds of art, and I’m interested in quality. I am aware that the concept of quality is debated, and I also understand that the definitions of quality we have may be too narrow. The concept of quality has recently been taken up by Sápmi artists and I completely agree that they have the right to define their quality. On the other hand, art has traditions, and the traditions are being renewed. Still, something basic remains; the premises of Western art and how they are defined in different cultures.

I am aware that I can be challenged in what I say here, but this is something I need to trust when I work because otherwise it makes no sense. I am also an advocate of art’s freedom and think that this freedom is the most important inheritance that we have.

From the opening of an exhibition of art from the Soviet Union 1974 in the Helsinki Kunsthalle. Kari Jylhä, the chairman of the Artists’ Association is on the way to the lectern and Finland’s president Urho Kekkonen sits in the front row. The exhibition was shown at the same time as Ars74 with the theme of realistic art.

MM: After working at the Nordic Arts Centre, you first went 1990 to Moderna Museet and then after that to Kiasma, right?

MJ: I was six months 1990 in Stockholm as a substitute curator. The Museum of Contemporary Art was founded in Finland the same year and I got the job as chief curator that same year.

PE: Did you curate anything at Moderna Museet?

MJ: Björn Springfeldt was the director then, and I was standing in for one of the curators who had a leave of absence. Björn and I had co-curated Borealis in Malmö together some four-five years earlier. He invited me to come and work in Stockholm, but I was there only for a short time as the new job in Helsinki started. It was a contemporary art museum in my hometown. Moderna Museet at the time was a museum with quite established ways of working and focuses of interest. I did not do anything special there. I wrote a few texts and worked a little with the collection. Directors at the time usually wanted to decide the program themselves and I had used to being able to have “a voice” in the program planning. I do not mean the whole program, just to be able now and then to realize what interested me.

PE: Speaking of this type of structure, I am wondering if you have encountered other types of misogyny over your career?

MJ: Misogyny has been part of the normal social situation in the art world for a long time, but strangely I have not experienced it to any mentionable degree. Women are also in majority among people working in art museums, so misogyny is rare there. However, it is difficult to say if I did not get a job that I had applied for because I am a woman or was it for other reasons. I have not applied for so many jobs that I cannot say anything definitive about this. Women artists are also very strong in our country, so they are treated with respect, at least, in professional situations.

MM: Your years at KIASMA were very important, both in a local and in an international perspective, and you went there from Stockholm?

MJ: The new Museum of Contemporary Art was first located in the old Ateneum building. After working two years there, I took a year’s leave 1992 to work with Artscape Nordland in northern Norway, a project that I found extremely challenging and exciting. I can also say that this year taught me a lot about how to communicate about contemporary art with people who have no background in it. It was a time when” freedom of interpretation” was intensely advocated and discussed and I was inspired by it. People don’t need to be taught anything to be able to encounter art. However, I also understand that people feel safer with some background information. Interpretation in general is a fascinating area that still greatly interests me.

Thr press conference of a British exhibition in Helsinki Kunsthalle 1975 arranged by the Artists' Association.

PE: How did Artscape Nordland start and what is your involvement in that?

MJ: There was a meeting in an island municipality in the county of Nordland where AK Dolven was invited to talk about how to develop the art scene in this northern area. She was living both in the Lofoten Islands and in Berlin at the time. She thought that what she likes about Berlin is that there is a lively art scene, and many artists are living in the city. What she loves about Nordland is the landscape, the light, and the proximity to the ocean. Her idea was to combine these two by bringing international, interesting art to Nordland. It was also a time when “site-specific-ness” was in focus.

Press conference of Markus Raetz' sculpture Hode in Eggum in the Lofoten islands 1992.

She told me about the idea that I found fascinating. The fact that it all happened was that the county had a really brilliant chairman of the county council Sigbjörn Eriksen. He pushed the project forward together with the then chief of culture Aaslaug Vaa and other capable people working in the county administration. They invited me and three other curators (Per Hovdenakk, Angelika Stepken and Bojana Pejić) to choose the artists for the project. The project caused an intense political schism in Nordland and resulted in a lot of opinionated writing in the regional press, but in the end, thanks a lot to the then county chairman and chief of culture, it could be realized. But many local artists were against the idea about tax money being spent on “modern” international art. You know, that type of discussion that happens almost everywhere. The idea was to have a sculpture in each of the Nordland municipalities. The artists could choose the site in the municipality where his/her work would be situated.

I had only recently started to work at the Museum and thought that my involvement in Nordland would end after the work in the selection committee. But it proved difficult to find any Norwegian curator/critic/art historian who would be interested in working with the project and eventually they contacted me asking if I could come and work with the project. At first, I thought it was impossible, but realized that there may be a danger that Artscape wouldn’t even start if they could not find any professional to launch it. All the municipalities in Nordland had been contacted. Some municipalities declined, but today 36 sculptures are placed in 35 communes. It took a much longer time, from 1992 to 2015, to complete than was first thought, but I have been working on some aspects of it all the way along with my other jobs. Some of the artists I have also chosen beyond the initial selection for different reasons like that the artist first invited was not interested in it, had no time for it, or the fee was too low.

MJ: The official opening of Artscape Nordland program. Kain Tapper's (5th from the left) sculpture A New Discussion was the first to be inaugurated in the presence of King Harald and Queen Sonja 1992. Aaslaug Vaa, the chief of culture of Nordland county is standing next to the Queen.

MM: When you started as chief curator at the Museum in Helsinki, who did you work with at the time, who were the other curators?

MJ: During the first years, when the program was not yet fully developed, I was engaged both in exhibitions and collections. A few years later, Helka Ketonen was appointed, and her field was collections. Asko Mäkelä came after her and was working with new media. When Asko moved on, Perttu Rastas was appointed in his stead. Tuula Arkio was the director at the time.

PE: It is a huge responsibility; did you have any thoughts about widening the collection in any particular way at the time?

MJ: The Museum of Contemporary Art is a part of what is now called The Finnish National Gallery. The other museums are Ateneum and Sinebrychoff. Each of the museums covers a time period. The collections of art after the 60s were removed from the older Ateneum to the Contemporary Museum. Ateneum is now covering Finnish and international art from about 1700 to the 1960s. Ateneum was run by a private foundation, but The Museum of Contemporary Art was founded in connection with nationalizing Ateneum and Sinebrychoff. Today, The National Gallery is run as a public fund.

Museum work was new to me when I started, so it took me some time to understand the structure and what could be done. Tuula Arkio and I agreed that it was important to go back and see what was not represented in the collection. It was mainly photography and new media, but also the conceptual tradition was mostly neglected.

ARS exhibitions have a tradition in our country. The first international survey was arranged in 1960. We made Ars95 in the old building. The new museum building Kiasma opened in 1998 and the next Ars was made ARS01. When Ars 01 was arranged, globalism was a topical issue with its focus on the encounters of different cultures and what they lead to. The theme was “the third space” and defined as “unfolding perspectives.” It turned out to be really dramatic as while we were preparing for the opening during the autumn the catastrophe of 9/11 happened, and suddenly the exhibition turned highly political. It was interesting to see this. We had thought about this as an entirely cultural manifestation, but the reception seemed to be of great interest mostly to the political journalists rather than to art critics. The theme “the third space” was inspired by Homi Bhabha. Irit Rogoff gave a lecture in the seminar arranged in connection with it as well as participated in the discussion on Sveaborg which we made in collaboration with NIFCA.

MM: ARS95 was somehow a landmark exhibition as it came after a period of economic depression and in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union. Its thematic premise was the private and the public.

MJ: I don’t like very strict interpretations of what, for instance, concepts like what “the public” or “the private” mean purely theoretically. In a way all art contains elements of private and public, and we didn’t have any deep philosophical or conceptual discussion about what it would mean in the exhibition. It was intended more like a survey exhibition on art with some focus on art in the Baltic countries. Post-communism was not a theme in this connection even if it was addressed in some of the works. Generally, it could be said that the art world in the Nordic countries, had become more confident and were joining in the international discussion. Earlier the thinking in the Nordic countries had been that we were more onlookers of what was happening in the centers of art and either neglected it, or were highly influenced by it, but did not engage in it. Slowly, in the 80s and 90s, we started to trust ourselves to also be equal and also initiators, not just receivers. It is difficult to exactly know what struck the nerve with ARS95, but my former students have also spoken about this.

The Museum of Contemporary Art (since 1998 Kiasma) was officially opened in the Ateneum building 1991. The opening exhibition was Lothar Baumgarten's "Baltic window". Maaretta Jaukkuri and Lothar Baumgarten in the picture.

MM: When you came from Stockholm to start at the Museum, what were you thinking about its future direction? Then in 1998 Kiasma was opened. The first years at Kiasma were extremely interesting, also from an international perspective? How did you envision the overall program?

MJ: I had had a lot of different experiences in different situations and seen a lot of art, but then I think you just have to be curious and see what is going on. Museums are often careful in showing new art and think some time is needed to see how it “weathers”. We thought that we could test interesting things also in a museum of contemporary art. Is it interesting or not? Will it keep its meaning or value, or will it just fade away? Maybe curiosity is a characteristic that I have.

PE: You make it sound so easy, but I know it's not. There are so many barriers, you have to fight to get a budget, fight political battles, and ignorance. Do you feel like you have battled something more, or something less?

MJ: I don’t often take part in public discussions, as it is not my way of working. I think I have enough of a forum just by making these exhibitions. Budget is an eternal issue, of course, but then during the first years of Kiasma, we were economically quite privileged, as there was quite a lot of sponsorship. Finland had been going through a very difficult economic period, which still was felt in these early years. Despite this there was also state support. As an example, I could tell you about a minister of finance who decided that since we now have this brand-new building, we needed something to show there. The new museum was very much in focus in the country. I do not know whether he knew that the new museum actually inherited Ateneum’s post-60s collections. Anyway, it felt great to be able to buy new works at this stage.

A new institution was born, so there was a lot of internal organization, employing people and seeing how everyone got along, etc. I don’t think there were any battles of the kind that you are referring to, but there was a lot of hard work. And we had to carefully think what messages we are going to send, and what does this all mean? That was the most challenging part of it.

Tuula Arkio, Louise Bourgeois and Maaretta Jaukkuri in Bourgeois’ studio in New York in preparations for ARS95.

MM: I remember those early days of Kiasma, it was really the place, people coming in from an international scene, going to the openings and there was a lot of excitement, the whole feeling in Helsinki was great because of what was going on in Kiasma the first years when you were chief curator there. It obviously worked.

MJ: There was international interest, and it naturally was inspiring for us. Artist, journalists, and colleagues visited the museum. We had around 200.000 visitors a year, which is a lot for a museum of contemporary art. It was quite steady, the number was even higher during the opening year, but then it was more or less steady. Today the number of visitors even exceeds these. It's not considered to be a particularly weird or difficult thing to go and see an exhibition at KIASMA today, actually the contrary is true. Kiasma has also had a young audience throughout its existence.

MM: It is a positive thing that it has established itself, but, of course, there are always a lot of divided opinions when it comes to contemporary art. It is probably as you say, people are more familiar with contemporary art now. And there are more exhibitions and galleries for contemporary art and so on. The situation has changed so much since the early days of KIASMA, that there is now a wider audience.

MJ: The concept or definition of contemporary art is something new. The discussion is not any longer whether something is considered modern or postmodern, it's simply contemporary. Contemporary art, as we know, is defined by many different directions and interests. Contemporary art is also close to everyday life and it doesn’t try to reach any “mystic truths.”. I am however a bit worried today about the idea that art should save the world or stop climate change. We know that art cannot save the world, but it can save or at least help and give strength to all of us who live in this dangerous time. I’m worried about art being used. I don’t think it should be used in any kind of way, politically, or any other way.

The curators of the worldwide exhibition arranged in the program Copenhagen Cultural Capital 1996.

PE: Do you believe that art can be completely free from these structures?

MJ: Well, it cannot be completely free, but it must be on the way. Freedom is a totally philosophical, almost abstract concept. I’m not referring to that. If someone wants to discuss climate change through art, he/she is naturally free to do it.

MM: You were the first professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki of the so-called Praxis program. What were your ideas and thoughts about being the first professor of that program?

MJ: By this time, I had been a professor at the Trondheim Academy of Fine Art. The program there was for art and architecture students and called Art and the Common Space. The concept of common space enables a wide variety of approaches both to art in public spaces as well as to this time. In Trondheim the focus was on art and architecture and in Helsinki the focus was on art and curating. I’m not so interested in techniques of curating because I think as curator you have to be open to all kinds of information and situations and to be observant. It is usually the content of an exhibition that guides the way of composing it. All the Praxis students I had in this first MA course were artists. This guided the program quite a lot as the students already had experience from exhibitions.

This year I was advising a Praxis student who was doing her MA thesis about curatorial studio visits within the Art Academy. She offered the visitors a massage in exchange for the students showing and telling about their work. In this way she turned the visit into a performance. At first, I thought this was strange and perhaps not ok, but in the end, she finished her MA in quite an interesting way. For me, visiting studios is a very sensitive issue, so I was afraid she was making a spectacle out of it, but it worked out fine.

Maaretta Jaukkuri with Ilya Kabakov working with his exhibition in the Museum of Contemporary Art 1994.

PE: Yes, it is not necessarily known outside the art world how sensitive studio visits are, and sometimes internal hierarchies are disturbing. The curator is generally considered to be a person in a more powerful position than the artist. How do you see your own role in relation to this?

MJ: The power issue is very disturbing. We have had a period of “star curators”, which luckily is more or less over now. They contributed to strange ideas about curating and what curators do. The conflict between artists and curators increased. The curators were seen to “steal” attention from art and artists and use it for their own ends. That kind of discussion seems to have calmed down now. Sometimes we forget that a curator, whether working in an institution or independently, also “sells” his/her plans. Within an institutional context you also convince your colleagues about your ideas, and sometimes the concept may get a little bit diluted in this process. Nowadays, there are also educated producers, and they have a say in this. We have to also keep in mind that the technical staff at the museum also can influence the process and the budget defines a lot. It is a complex system, and it is not as simple as it sounds. Kiasma fortunately has had and has a really professional and technical staff interested in art.

Prof. Zygmunt Bauman with his wife Janina Bauman visiting Kari Cavén's sculpture in Beiarn at the time he took part in a seminar about Artscape Nordland. He also took part in the curators' seminar arranged by Nifca 1997.

MM: Going back a little, you had students from architecture as well?

MJ: The original idea with the course in Trondheim was art in public space. It was a new program. I thought “art in public space” sounds a bit boring as a title and it could be more interesting with “art and common space”. The common is here is more connected with presence and sharing. We studied all kinds of issues related to this concept quite freely. Maybe it was because I had just finished the first phase of Artscape Nordland, the sculptures in northern Norway and in communities with little tradition of contemporary art. It was more interesting to see what happens in the encounters between the sculptures and the communities around them. When the work was finished and unveiled in the presence of the artist, with speeches, music and the rest of it, something happened. The works seemed to be adopted by the people who live there, and they started to protect them. They became proud of their artists, and in some cases, contact is kept till today.It happened in almost every municipality that we worked in.

MM: The reason I ask this is because I visited the Art and Common Space program once, and it was interesting how the discussion about common space went into so many directions. It is such a rich concept, and it was inspiring to listen to the students there.

MJ: I was happy with the program because it inspired us all. I worked in Trondheim full time for three and a half years and continued some years on a part-time basis. We had visitors, made study trips and I kept on preparing new lectures. I was very happy about being able to read up on a wide range of topics, something you don’t have time to do when you work in a museum.

Maaretta Jaukkuri curated the Nordic Pavilion at the Venice Biennale of 1998 The artists participating are from the left Per-Inge Björlo, Rolf Hanson and Jukka Mäkelä.

MM: Also, you started very early with this concept of the common space in the art academy context, it wasn’t talked that much about it in those times. As you are actively curating and working, I was wondering what are the topics you are curious about at the moment? What are you researching at the moment, and what kind of artists are you working with?

MJ: I work on a very small scale today, and it is mostly with people I already know. I think my interests are very much the same, but the times have changed, which also means that perspectives change. I am very interested in the time in which we live, so not only common space but also common time, that is what I’m really interested in. This is what I am reading and thinking about. Art makes visible invisible things. Art happens in people and between people. This is my interest. It may sound a bit grandiose, and I say it only in this kind of situation in which art is talked about in an abstract manner.

PE: Can you mention any projects you are working on right now?

MJ: Well, I’m working on a smaller Nordic outdoor sculpture collection that is slowly being made in the Hanaholmen Cultural Center (Swedish/Finnish) in Espoo. There are already three Nordic sculptures. In the Hanaholmen project the concept is simply the seasons. This comes from the experience that we tend to forget that we also have winter with lots of snow that totally transforms the site. This is also a way to give the artists freedom to interpret the theme in the way they want. I am also invited to work in different juries and then I write.

MM: I am curious to know more about what is going on in the Maaretta Jaukkuri Foundation in the Lofoten Islands, I remember hearing the story about how it got started, could you tell us the beginning of it?

MJ: I was working in Oslo and met AK Dolven, whom I had known a long time and as I already told, Artscape Nordland was her idea. She had bought land to build a studio in a village where she already had a house in Lofoten. In connection with the purchase, she got a little piece of land that she had no use for. She asked me if I would like to have it. And I said, well, yes, ok, it would be nice to own a little piece of land. This is how I became the proud owner of a little place in Norway. Of course, I had no money to build there, just the idea of having it was enough. A few years passed when I suddenly got an e-mail from Antony Gormley telling me that he and his studio – he has a large studio in London with several people working there – had been contacting artists with whom I had worked over the course of my career. They were asked to donate works to an auction to be arranged to finance building a house in Lofoten. Now they had the works, and a charitable auction could be arranged. I had heard nothing about this before. I was stunned and did not really know what to think.

And then the auction happened. Even at Sotheby’s they thought it was such a nice story that they didn’t take any commission on the sales and the entire sum was given to build the house. I think the sum from the auction added up to around four million Norwegian kroner. I asked the Finnish architect Kimmo Aslak Liimatainen whether he would be interested in designing the house. I knew him as he had a couple of times been involved in Kiasma’s exhibition architecture with his colleagues. The four young architects who had won 1996 had won the Golden Lion in Venice right after graduating. We also got some more financial support from Innovation Norway so the building was made possible. To handle the economic situation, a foundation was established. I had always thought that if a house ever would be there, in the beautiful landscape and fascinating light, I would, of course, share it with friends and colleagues. I wrote a text about this with guidelines for the Foundation. The Saastamoinen Foundation and the Kone Foundation have now funded the residency or fellows program, as we prefer to call it, for a period of three years. This first period is now over. The Saastamoinen foundation will continue supporting the program for five more years.

The house of Maaretta Jaukkuri Foundation.

We also arranged a seminar in Kabelvåg in Norway with the theme “Stories told and re-told”, and we are planning another one on aspects of tacit knowledge. It was supposed to happen last autumn, but due to the pandemic situation it has so far been postponed. It will most likely take place next year in connection with the LIAF biennale. Tacit knowledge is interesting in all sharing of experience and knowledge. For instance, in Lofoten they have had fishermen sharing their experience of the ocean and fishing with academically educated biologists. And if one thinks about teaching art, tacit knowledge is also important. Storytelling and tacit knowledge are themes I am interested in as they are present both in life and in art.

The whole operation is small in scale and the house is not very big. MJF can host about five fellows a year. But people who have been there are generally quite happy. The basic idea is that people normally don’t have time to slow down and just ponder. You don’t have to produce anything or follow daily routines there; you can focus on whatever you feel like doing and the milieu surrounding it is truly dramatic and beautiful. And it even has a nice Finnish sauna. Sometimes I still can’t understand that the house really exists, and that the program is running.