The Birth of a Dying System

Alexander Stagnell

As Putin announced his “special military operation” in Ukraine on February 24, 2022, a forgotten figure in International Relations thought found himself thrust back into the limelight. John J Mearsheimer, one of the leading figures of twentieth-century realist thought, had spent the last thirty years in the shadow of an IR field dominated by the optimism of liberal internationalism. Mearshiemer, who had been issuing ominous warnings about Ukraine since the early 1990s, in many ways embodied a spirit that the world tried to leave behind after the fall of the Soviet Union. His 1993 claim that “pressing Ukraine to become a nonnuclear state is a mistake” could not have been further removed from the words of Bill Clinton, who summarized internationalist hopes for West-Russia relations after the 1997 Paris summit:

I know that some still see NATO through the prism of the Cold War, and that especially in NATO’s decision to open its doors to Central Europe’s new democracy, they see a Europe still divided, only differently divided. For this new NATO will work with Russia, not against it. And by reducing rivalry and fear, by strengthening peace and cooperation, by facing common threats to the security of all democracies, NATO will promote greater stability in all of Europe, including Russia.

Mearshiemer’s view of the world, that states find themselves in an anarchic system furthering a constant struggle for power rather than mutual prosperity for all, quickly found its way into the rhetoric of global leaders. Just a month after Russia’s invasion began, U.S. President Joe Biden, in a speech in Warsaw, said of Putin “this man cannot remain in power”. And after Sweden and Finland announced their joint intention to join NATO, similar rhetoric was heard from military and political leaders. Swedish Chief Commander Micael Bydén, at the annual Society and Defence conference, began his speech with images from a war-torn Ukraine, asking rhetorically “Do you think this could happen in Sweden?” He then went on to assert that “Russia’s war against Ukraine is a step, not the final goal, with the ambition to establish spheres of interest and to destroy the rule-based world-order”. The Finnish military went even further into realist rhetoric, completely abandoning the more pragmatic strategy of Finlandization that had defined the Nordic brother countries during the Cold War. In an interview with the Financial Times, the Finnish Chief of Army Logistics and Material claimed that “Russia respects power. Power consists both of the will and the capacity. The will is in place. The people’s will to defend the country is probably the highest in the world.”

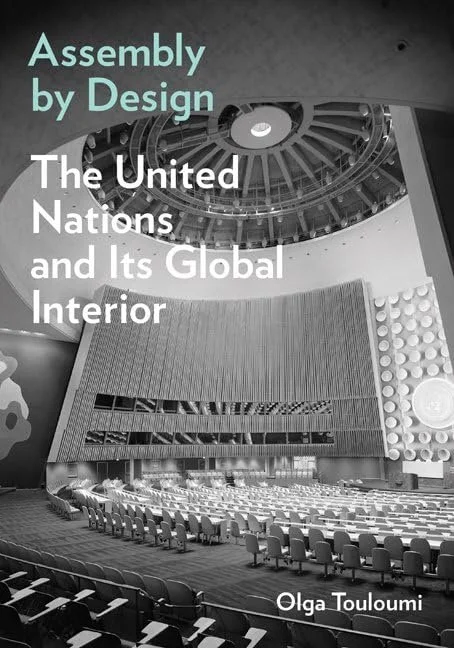

As we may be witnessing the long-prophesied end of the liberal internationalist order, we are prompted to reflect on its history as it stretches back to the proponents of perpetual peace during the French Revolution. In Olga Touloumi’s Assembly by Design: The United Nations and Its Global Interior (University of Minnesota Press: 2024) we get to follow how a key part of its success during the twentieth century, the creation of the United Nations, employed visual and architectural language to further this globalist vision.

Boris Yeltsin and Bill Clinton in 1996.

Touloumi’s work on the emergence of the United Nations’ architectural ideology fits within broader academic trends of examining what could be called the aesthetics of diplomacy and international relations. While much of this scholarship has focused on the Early Modern period, Touloumi brings the question of how different spaces of diplomacy shape our comprehension of international relations into the twentieth century. This story begins at the end of the Second World War with two key events that would come to stage a post-war world: the 1945 San Franscisco Conference, which attempted to secure peace for the future by creating the United Nations Charter, and the Nuremberg trials, designed to punish those responsible for war and to restore dignity to mankind. And behind the scenes, the U.S. Government, together with its military and emerging intelligence agencies, was planning how these highly public spectacles could be used to establish a new world order. But to achieve this, they needed the help of designers and architects. Touloumi demonstrates how both the conference and the trials became testing grounds for many of the problems and ideas later confronted in the creation of the UN’s globalist architecture. One major issue was how to transform the traditionally secretive realm of diplomacy into something that could be communicated to a global audience. This was not only accomplished visually, as press photographers were allowed to capture images of ongoing negotiations or Nazis on trial, but also performed acoustically, among other things through the introduction of technologies allowing for simultaneous interpretation. As an effect, the interiors of these institution became the new stage for global politics.

Nuremberg Trials: looking down on the defendants' dock. Ca. 1945-46.

The metaphorical and literal architects behind both the San Francisco Conference and the Nuremberg trials aimed to present an image of a fair, transparent, and therefore democratic global bureaucracy capable of both securing peace and administering justice. And it was the specific organization of space that allowed for this to happen. So, it was with an eye towards establishing a more permanent platform to perform this system on that planning began for the now famous UN General Assembly building in New York. In the book’s second chapter, Touloumi explores how communications acted as a framework shaping even the physical construction of the UN. Initially, she notes, the question was whether the UN complex should be envisioned as a world city, harking back to late 19th and early 20th century attempts to replace the dying colonial order with a new model for global governance, or as a UN headquarters, an image steeped in military tradition. The debate was quickly resolved, Touloumi writes, instead placing “communications and technological systems at the heart of the literal and metaphorical architecture of the UN.” [97]

Despite those involved in bringing forth a new international order had the explicit intention to create a communicative democracy, the book highlights how a fear of the masses and Hitler’s demagoguery shaped the project. Technological and architectural features were imagined as ways to combat the demagogic threat that loomed over any would-be global government, just as they were used to prevent another risk: the UN being turned into a stage on which actors performed for the sake of their own vanity. But when the General Assembly Hall was finally completed it featured designated areas for the public and the press, loudspeakers that made it seem as if the sound emanated directly from the speaker, and the UN emblem as a focal point of onlookers from around the world. These elements together completed what Touloumi calls a “simulacrum of media transparency, realism and global democracy.” [164] By creating an architectural and acoustic illusion of intimacy the UN projected an image of being in direct contact with a global public, while continuing to perpetuate existing power structures behind its façade.

United Nations General Assembly hall in the UN Headquarters, New York City, February 2024.

In the fourth and final chapter of the book, Touloumi examines how the visual language of the UN headquarters was exported all over the world through the concept of “itinerant platforms”. The UN sought to export a format for organizing global public life in the image of is headquarters, all the way down to the local village center. Guided by metaphors of networks and communication, political questions were explicitly forbidden, instead favoring the language of technocratic internationalism. Rather than offering financial support, the UN wanted to provide a communications infrastructure capable of connecting the most remote parts of the world with the knowledge of international experts, aiming to educate its global public. This “culture of assembly” coincided with the moment when significant parts of the world were going through the process of decolonialization, lending these struggles an air of objectivity and transparency while also tying the edges of the world back to the global power center in New York. These itinerant platforms, Touloumi concludes, “traveled and organized publics around the world, proliferating and disseminating the ways of the organization as the habitus of liberal internationalism on the ground.” [213]

Assembly by Design paints a detailed picture of how the UN staged, and later disseminated, the vision of liberal internationalism in the decades following the Second World War. The reader also gets an insight into competing visions of this ideology at a time when they were engaged in a battle for hegemony. It offers a look behind the curtains, showing the (mostly) men and women working on erecting the stage which we have been taken as given for the last half-century of international politics. In her epilogue, Touloumi is also critical of many aspects of this work to ideologically shape the international space, even though she acknowledges how architectural choices at times made it possible for other voices to emerge. Although liberal internationalism espoused values like democracy, development, human rights, and aid, Touloumi argues that the form that these values took made their realization impossible. Influenced by architectural modernism, the architects behind the UN furthered a technocratic vision that not only staged the world, it also tied these global institutions to U.S. corporate interests. Touloumi therefore ends this history by emphasizing how companies involved in this creation, such as IBM and Chase Manhattan Bank, soon adopted the same aesthetics in order to associate themselves with the UN’s values, in turn transforming them into members of the same world society. The same effects were also achieved by Hollywood, contributing to this creation by projecting “the UN interiors and their architectural grammar as part of the syntax of global governance” [224], while educational institutions organized model UNs to teach “students to be part of this new world society, celebrating the UN General Assembly as a democratic public sphere where member states bring the interests of their interiors.” [225] However, Touloumi points out that furnishing international politics as a stage reduces most of the world to a passive audience, and while its actors might be capable of speaking, they have no ability to listen or to act. This, as she claims, undermines any real hope of a global democratic polity. Yet, Touloumi leaves us with hope, suggesting that by learning from this history we might “move together toward more just and open structures of society.” [227]

L'Hydre aristocratique. Paris, 1789.

As noted, it is only in the epilogue that Touloumi touches on the wider implications of this history, and it would have been interesting to see a more thorough exploration of this side of how liberal internationalism tied our understanding of global governance to U.S. corporate interests. The book also highlights many of the internal contradictions of liberal democracy, not least how its praise of the popular will and the people’s sovereignty is overshadowed by its fear of the masses and its demagogues. But it leaves these questions hanging. As a reader, I am left wondering how a truly democratic order of global politics would address these and similar issues. In a time when the liberal internationalism under US hegemony is under siege on all fronts – from China backing Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, via Israel’s dismissal of any U.S. attempt to impede the slaughter in Gaza, to Saudi Arabia considering accepting yuan for oil payments – the only publicly available vision for the future seems to be authoritarian nationalism. But this is nothing more than a return to the other great diplomatic ideology of the twentieth century: realism. As international politics seem to have entered a time of monsters, we certainly need to understand what is dying, in order for something new to be born.

Alexander Stagnell is docent of rhetoric at Södertörn University. He has authored Diplomacy and Ideology: From the French Revolution to the Digital Age (Routledge, 2020) and co-edited Populism and the People in Contemporary Critical Thought: Politics, Philosophy, and Aesthetics (Bloomsbury, 2023).