A Curator’s Journey - Eha Komissarov

A curator’s journey from Soviet colonialism through the Cold War, cowboy neoliberalism, and shock doctrine, to a sterilized history making

An interview with Eha Kommisarov by Power Ekroth and Marita Muukkonen

When Eha Komissarov, senior curator at KUMU Art Museum, describes how she feels about entrance fees having become the most important funding base for the museum, she sticks both middle-fingers in the air.

The opinionated grand old lady has been in the center of the Estonian art scene since almost fifty years, and she has been an inspiration for several generations of artists and curators. She is also commonly known for having been actively pushing a young generation to take over, a great deal of them being female. It is however clear that few others have the same high energy level as Komissarov, no matter how young they are. Komissarov has somehow managed to remain passionate throughout many structural challenges.

The following interview was made in the spring of 2019 at KUMU Art Museum in Tallinn, Estonia.

Inside the KUMU Museum, Tallinn.

Power Ekroth: Let’s start at the beginning, what did you study, was it art history?

Eha Komissarov: I was enrolled in the faculty of History in the Estonian University of Tartu in the end of the 60s and early 70s. I studied History and in the Soviet times this meant that I got a deep knowledge of the communist party and all the details of the Second World War, so it was absolutely a politicized subject. At one point a teacher who had a background in art history suddenly decided to give special courses, and I attended those for around two years.

Of course, as this was in the times of the Soviet Union, we started with Egyptian art, and finished with the Impressionists. This is something that still happens in Russia: the art history courses finish with the Impressionists or Art Deco. If you want to study the Constructivists, for instance, you need to find some very special courses or schools that are hard find; officially you still finish with the French Impressionists.

PE: Did you enjoy studying Art History?

EK: Yes it was much better than the regular courses. And it was such a great personal success for me, really a miracle, that I, immediately after, got a job in an art museum in Estonia, in Tallinn, at the Kadriorg Palace, Estonian Art Museum.

Kadriorg Palace museum.

PE: What was your first position at the museum?

EK: I was a person who would help important museum workers, an assistant of assistants you could say. The museum was very small, and in Soviet times the organization was very different. There was never any curatorial position. The exhibitions always had a historical view onto something from the collections, and everyone had a background from the department of History.

The museum was very small in comparison with what KUMU is today. The collections had some paintings, some sculptures, graphic art and also some applied art. Some items were European, but the strongest department was the Estonian art works. The situation of the country was anyway colonialized, and the position of art history was very strong, idealized of course as well as patriotic. We were all part of this Estonian machine of culture and we took the role very seriously.

I myself was very interested in contemporary art, and it was this time when I started to work in the museum that the Estonian contemporary art was extremely active, because a young generation started to make absolutely new things, and pop art came to Estonia.

PE: How did you come into contact with the artists and the contemporary art scene?

EK: Oh, Estonia is such a small country, we all knew each other… When I studied art history in the late 60s and early 70s, Pop Art was a big topic, and I think that in Estonia we were better informed than in Soviet in general, because it was easy to watch Finnish TV and radio, and there was also a Swedish Radio pirate station that we could listen to, near the Estonian border transmitting from a boat. This is how Estonia was connected to western culture, also to the music scene, not through some illegal or secret channels, but through Western media. Of course, no one visited American or European exhibitions, but we had some ideas about what was happening, via media and different western propaganda machines; these were obviously highly subjective channels, but nevertheless.

In the 90s this was on the other hand a cause of tragedy when the artists started to travel. They became totally confused, as there were opportunities to experience the works in themselves, and not only through perfect reproductions in publications. In reality the works had imperfections that disappointed so many artists. We had images, sounds and stories, myths about these artists and some information, but we had absolutely no theoretical or critical input. It didn’t exist. All the western art magazines were confiscated by the state. These newspapers from America or wherever, or artists’ magazines that came into the country somehow, were all confiscated and handed in to the National Library. As an official you were allowed to see them, but you needed to have the official papers. My director sometimes refused to give them to me, and asked: “Do you really need to go in the archives again? Do you have a valid reason?”

PE: So you were able to see some of them at least?

EK: I didn’t have any knowledge of the type of Art in America/Flash Art level of the English language, so I couldn’t read or understand much of it, but I, like some artists, looked carefully at the images. The pictures were examined over and over again. We didn’t read the explanations or got any theoretical background to the imagery. Later we understood the different directions of Pop Art from the anti-bourgeois, leftist, halfway communist art that they themselves stood for. Had they known, I’m not sure if any new art would have been made. [laughing] But visually, Pop Art was striking, and something that belonged somehow in Estonia. In Moscow it would have been considered as dissident art, but in Estonia there were some privileges as a sort of window to the west.

You know there were many thousands, I think around 20.000 Estonians living in Sweden for instance, so all the Estonians had some perspective and understood that things were very bad here. That is also why we had some very positive ideas about western art. It was a strange time and a strange life, as it was quite difficult to orient oneself into this world.

PE: How did you navigate?

EK: I think I made some very big mistakes. Sometimes I really enjoyed some tremendously ugly, primitive Pop Art. And also I was also very interested in the New York avant-garde, what they made in the end of the 60s. I loved minimalism, and “less is more” is still an influence for me.

PE: What do you mean by “mistakes”?

EK: Listen, I didn’t have any clear understanding about our local artists. No critical understanding, not even a space for understanding. The whole society was oriented towards admiring, but without any criticality, and didn’t have any spatial understanding. For artists it was very bad, as the critics were always supportive. There was a mythology of big artist heroes. That turned them in to mega egos. The main rule was that Estonian artists were always good, interesting and important. It is still ruined by these notions, I believe.

PE: Were there any shows here with non-Estonians at this time?

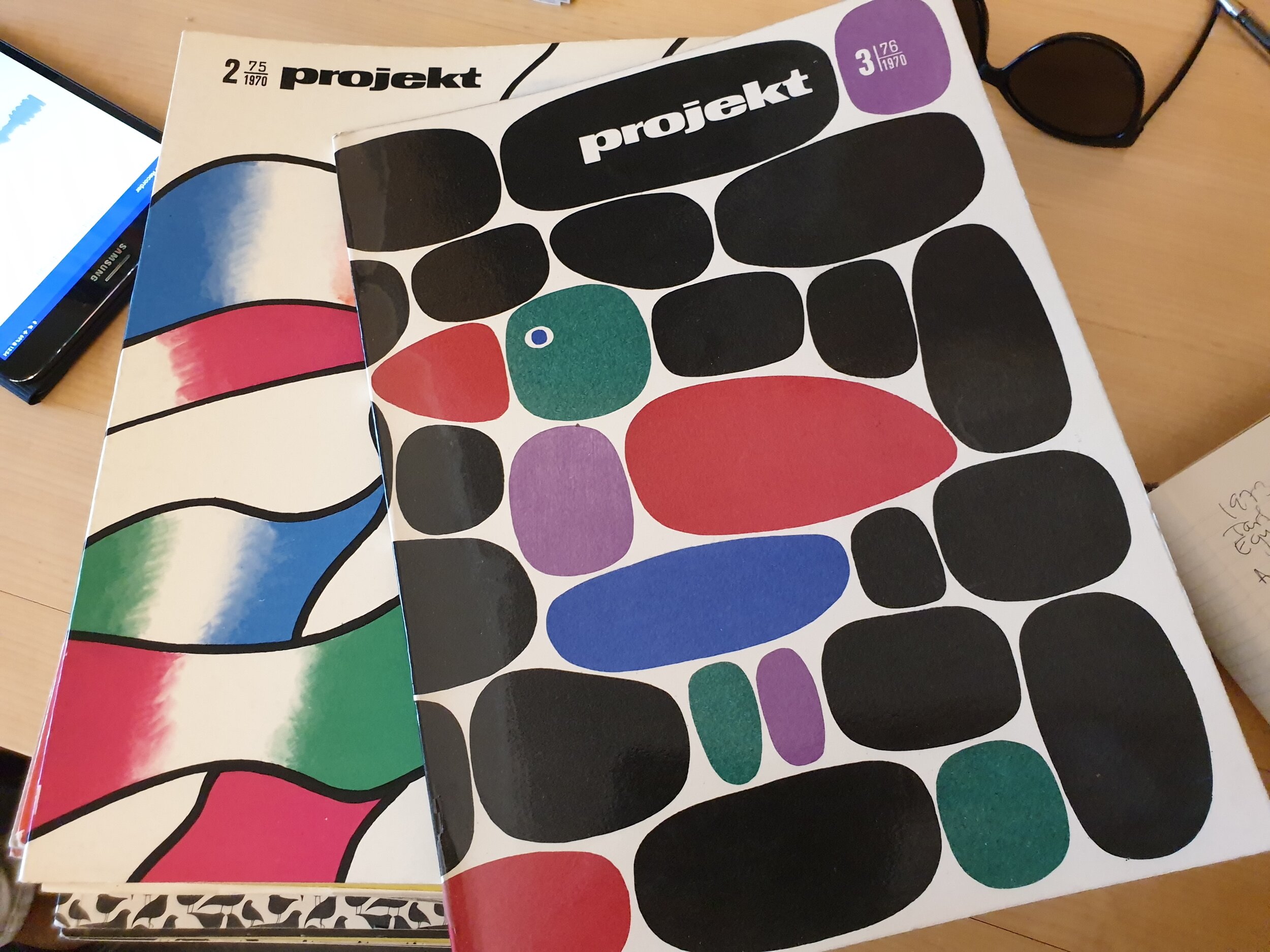

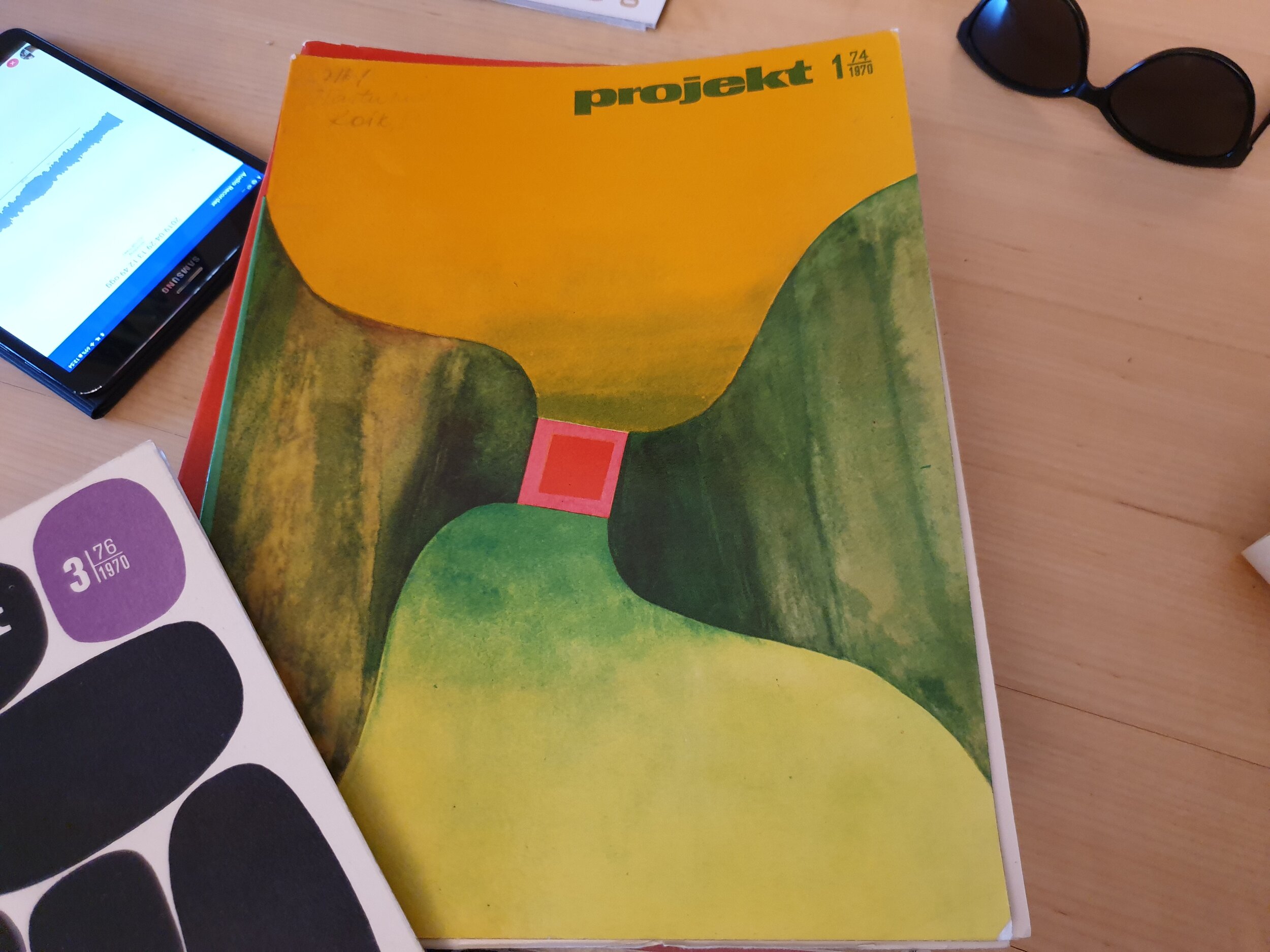

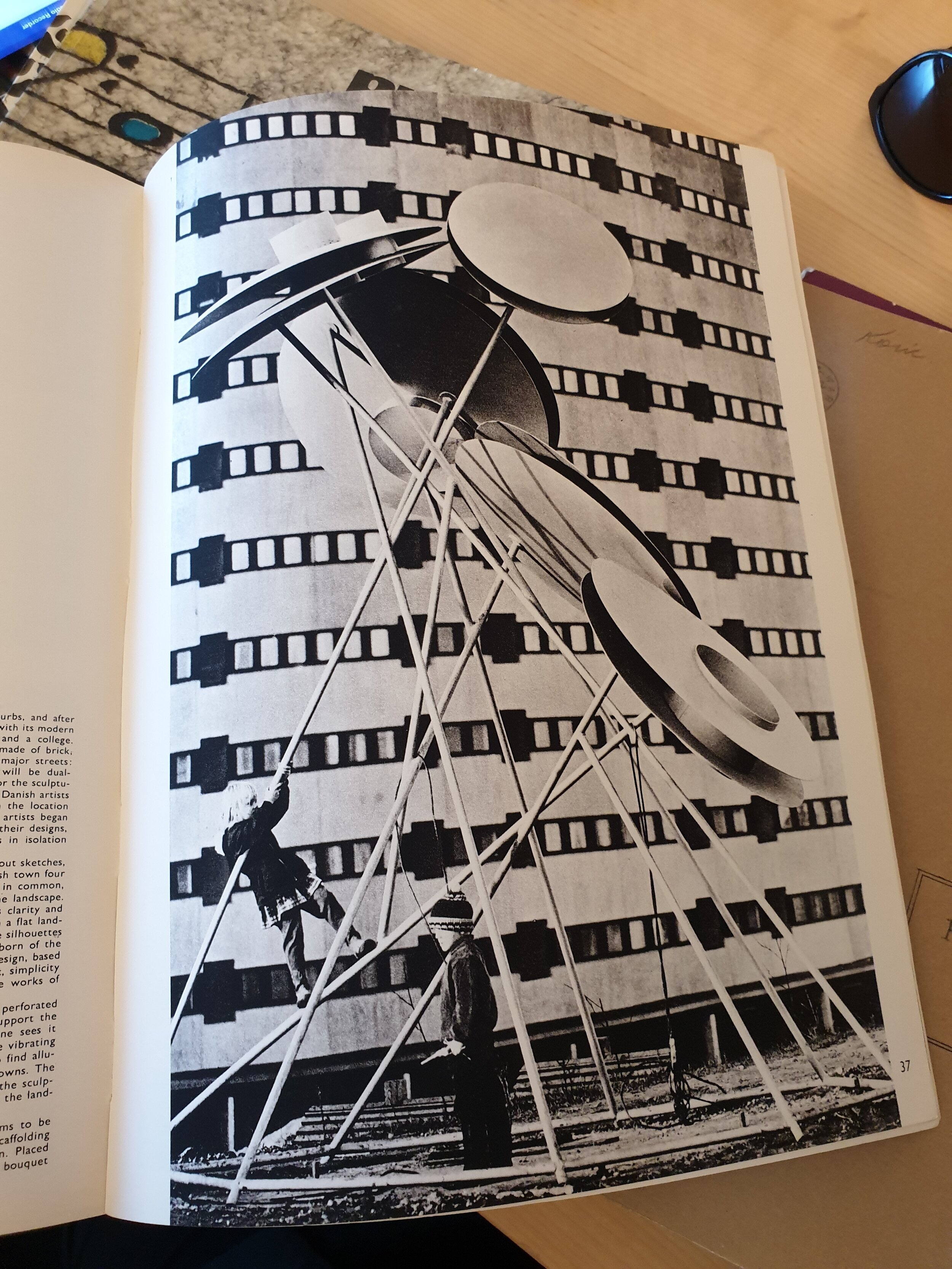

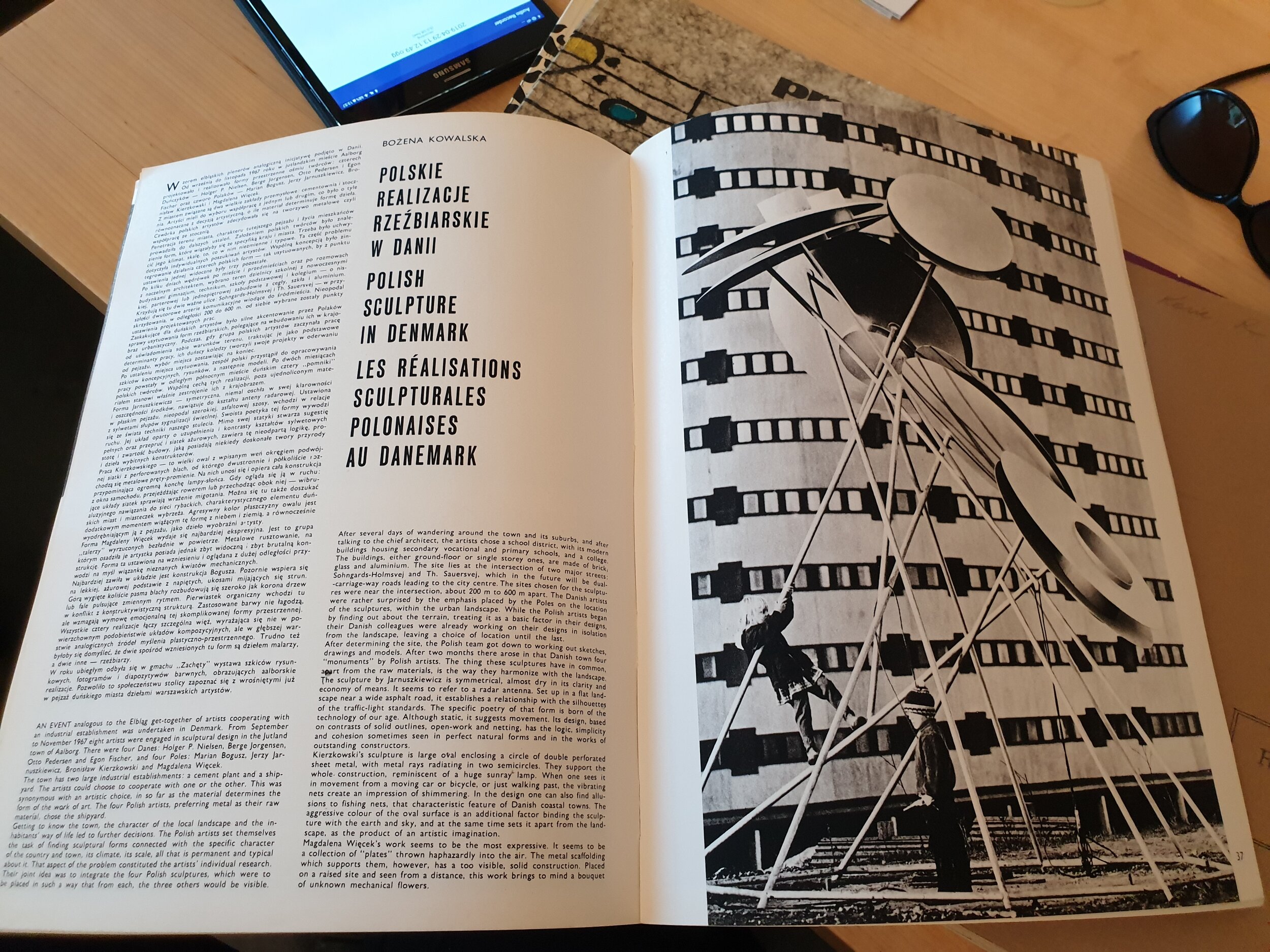

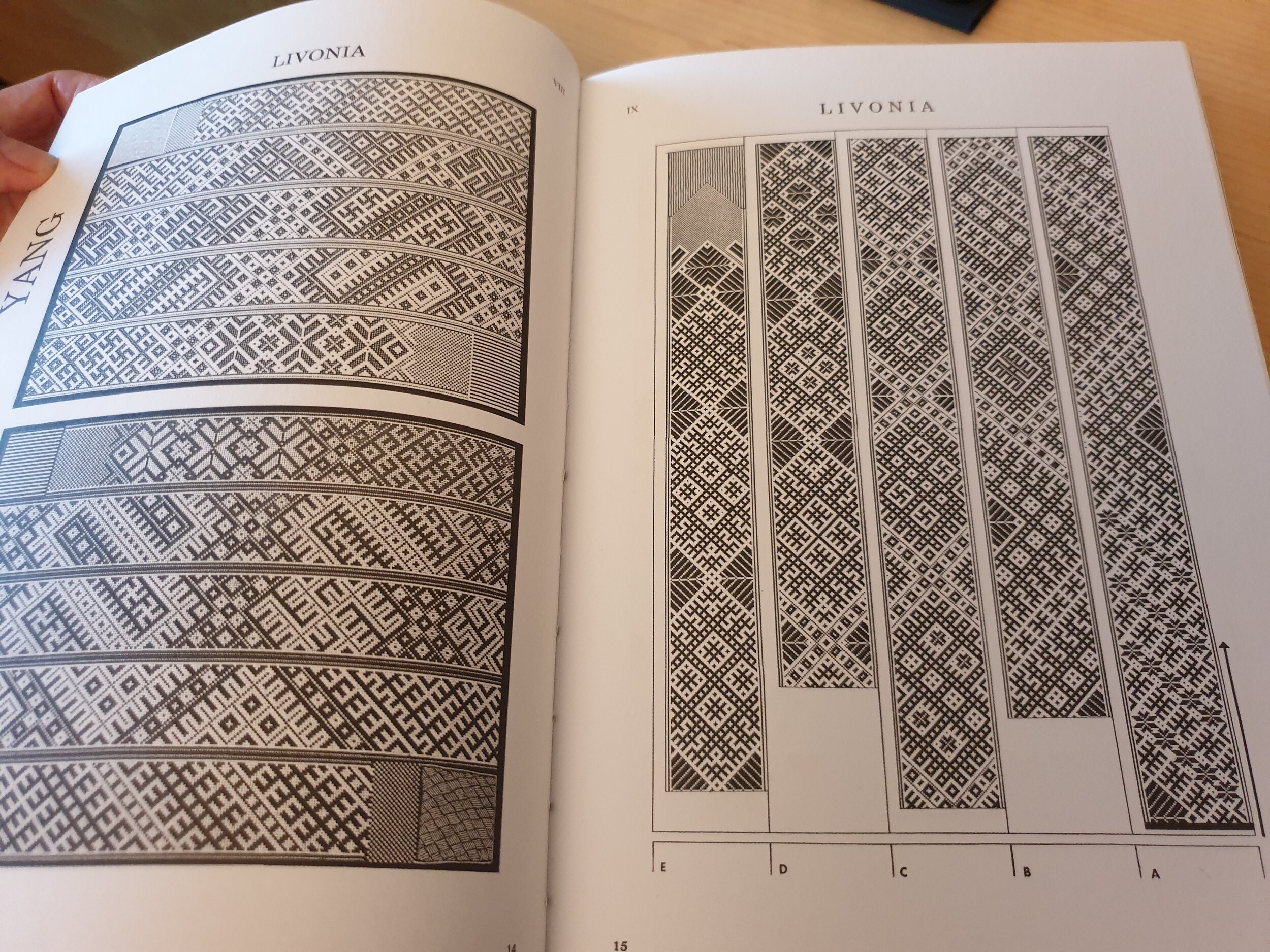

EK: No, we found all the information about artists from abroad through magazines. Especially one Polish magazine, named Projekt, was important. It was strongly oriented towards pop art and pop design, advertisements and so on. I think that all of our avant-garde artists got their information through this particular publication. As Poland belonged to the Eastern Block, some artists could visit Poland. In Krakow a big graphic biennial took place, and it was possible to visit sporadically.

PE: Were any Polish artists exhibiting in Estonia?

EK: No, no.

PE: Were any Estonian artists showing in Poland?

EK: A few times, but it wasn’t easy. Only Malle Leis, a pop artist, had a stipend and went to Poland. She also had some gallery exhibition in Prague. Other artists that wanted to show in the West sent their work to international fairs or exhibitions. For this reason a graphic biennial in Slovenia was really popular, they always showed Estonian artists who secretly sent their works through underground channels. The only capitalist country with which we had any contact with was Finland. Some Finnish artists came over here to drink and hang out with Estonian artists, it was a social phenomenon. Sometimes they tried to show artists from here.

PE: Did you go anywhere outside of Estonia yourself?

EK: I traveled for the first time during Perestroika, and it was to Finland. I was part of a joint exhibition where we showed contemporary artists from Estonia in Finland. I was responsible for the Estonian side, and Marketta Säppäla from the Pori Art Museum was responsible from the Finnish side. She later became the head of Frame. You see, for Estonia it took maybe two years before we understood what Perestroika meant and what we actually could do during it.

PE: Why was that?

EK: Well, Perestroika started very slowly. There were some very strange slogans coming from Gorbachev’s side, you never understood how to interpret it and what you really could do. You see, all the Soviet leaders were always talking about freedom, openness and internationalization, it was almost part of small-talk. When they said something like this, you needed to wait and see what happen: who was sent to camps and for what reasons? - for whom was the freedom actually meant?

Of course the talk about Perestroika was directed firstly towards the West, and the Finnish immediately picked up on it, and some of them came here to the artists’ society [Estonian Soviet Artists'Association] and wanted to make a joint exhibition with new (in the western view) progressive contemporary artists. Naturally, the artists’ society replied “No, no no! We will send you our choice of artists, some very good Estonian artists.” that naturally did not comply to what was considered progressive in the west. The Finnish side didn’t like that, and they had compiled their own list. Then there were some negotiations. But in the end the artist union here didn’t get to take part of the exhibition, and the Estonian official powers didn’t take any position in the debate. This cleared the way for the Finnish side to take on the artists they preferred. This was absolutely the very first big step for Perestroika in Estonian art.

If the Estonian republic had planned to make an exhibition in East Germany or wherever, you needed a certain license from Moscow. It was impossible to go anywhere without a license – this was how it worked during Soviet colonialism.

PE: How could you get such a license?

EK: You went to the Ministry of Culture, or to the artist’s union - not the local, but the party’s union of artists, or to the central party committee, the central department. You also needed a visa, which wasn’t easy either.

PE: But if you wanted to go to Moscow with a show..?

EK: That would have been really easy. I never had any dialogue with Moscow because in the eyes of the Soviet Union the Estonian Art Museum was a very small provincial museum with a small collection and it was not appealing to them. They liked the things we had from the middle ages however.

It was also essential to keep a low profile, because the next step would be that Moscow just took the artists away, to a camp or the likes. I personally didn’t know the school of Kabakov or the famous dissidents, only a very few Estonian artists had any contact with them.

PE: When did you start with the Estonian Art Museum?

EK: I started in 1973, while I was still studying. But let’s move to the library and I can show you some of the magazines and the catalogue I talked about.

PE: Yes, let’s go!

EK: Look, [pointing] here on the fifth floor of KUMU we display only contemporary art. This is my baby, I fought hard for it!

[stops and thinks]

Ah… Sometimes I have bad conscience – even if I think I did absolutely right, but… It’s difficult to explain to you.

During the 90s, it was like our history vanished, it literally ceased to exist. As a museum worker nowadays, you find that 30 years from art history has been cut out completely. It doesn’t exist. It’s simply a void. But remembering all these people, all this passion… so many lives, old names; these were exciting times, and suddenly they lost all relevance. For those who are still alive, it was a terrible experience to be someone of importance, and the next day you are not. But OK.

[Inside the library]

Here you find some old issues of Projekt.

PE: These are beautiful magazines, and it’s impressive that they come in Polish, English and French! It must have been widely spread.

EK: There were always some architecture, some criticism, information about some biennial, some art, some design. You can find it in Stockholm I am sure. Lots of images. And not only politically motivated artistic trends.

PE: Since you were working at the palace with its mainly historic exhibitions, how was it possible to make contemporary art exhibitions?

EK: In the Kadrirog palace I think we made five or six contemporary art exhibitions, because in Tallinn it was so difficult to make any exhibitions for contemporary artists, we simply didn’t have spaces for art then, professional spaces. Only the Art Hall/Kunsthalle and our museum. I think the initiative first came from the Artist Union, the bureaucrats wanted to be represented in a museum to become more important.

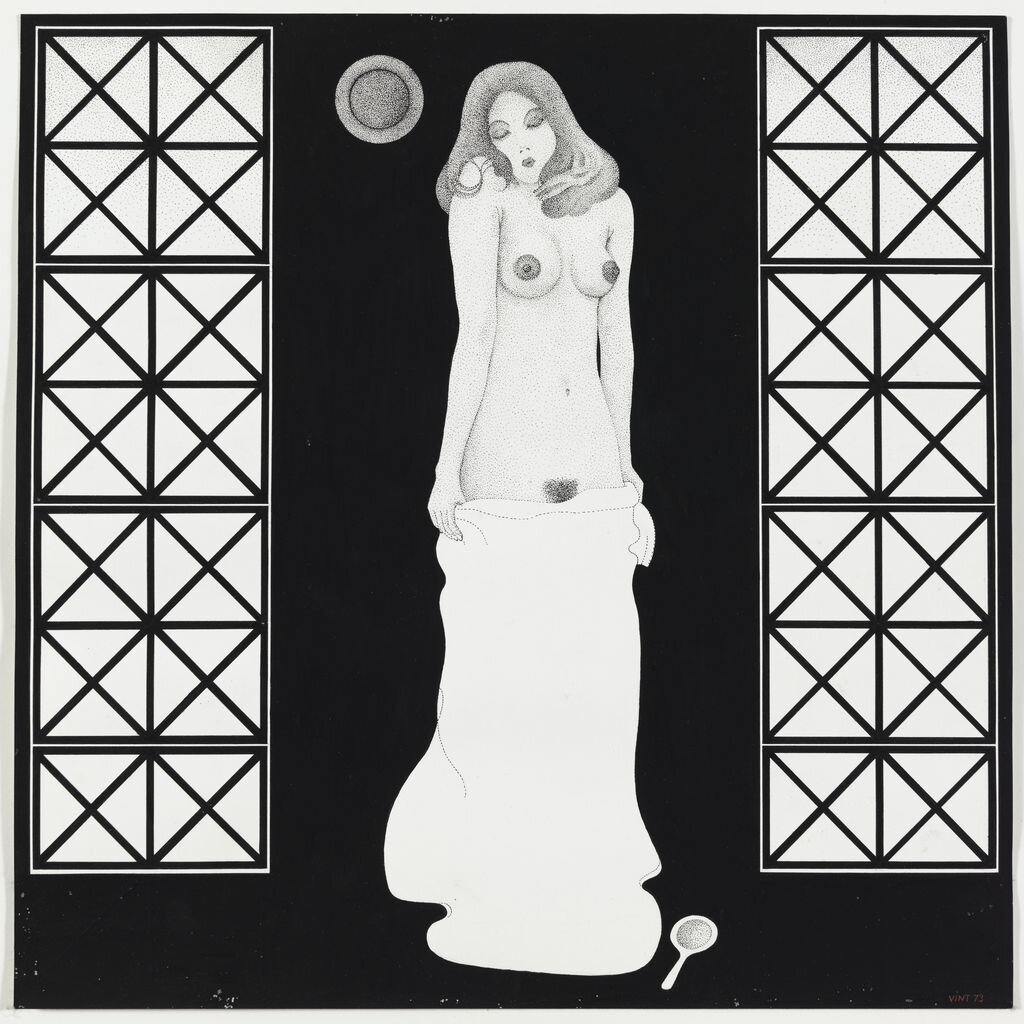

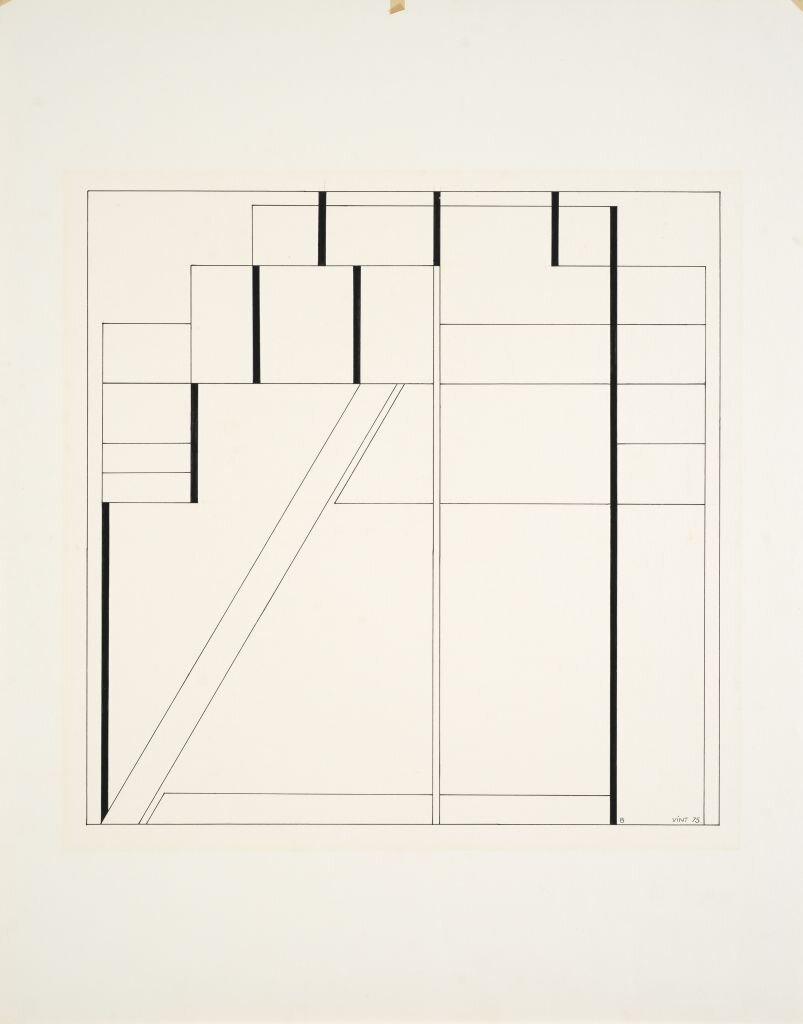

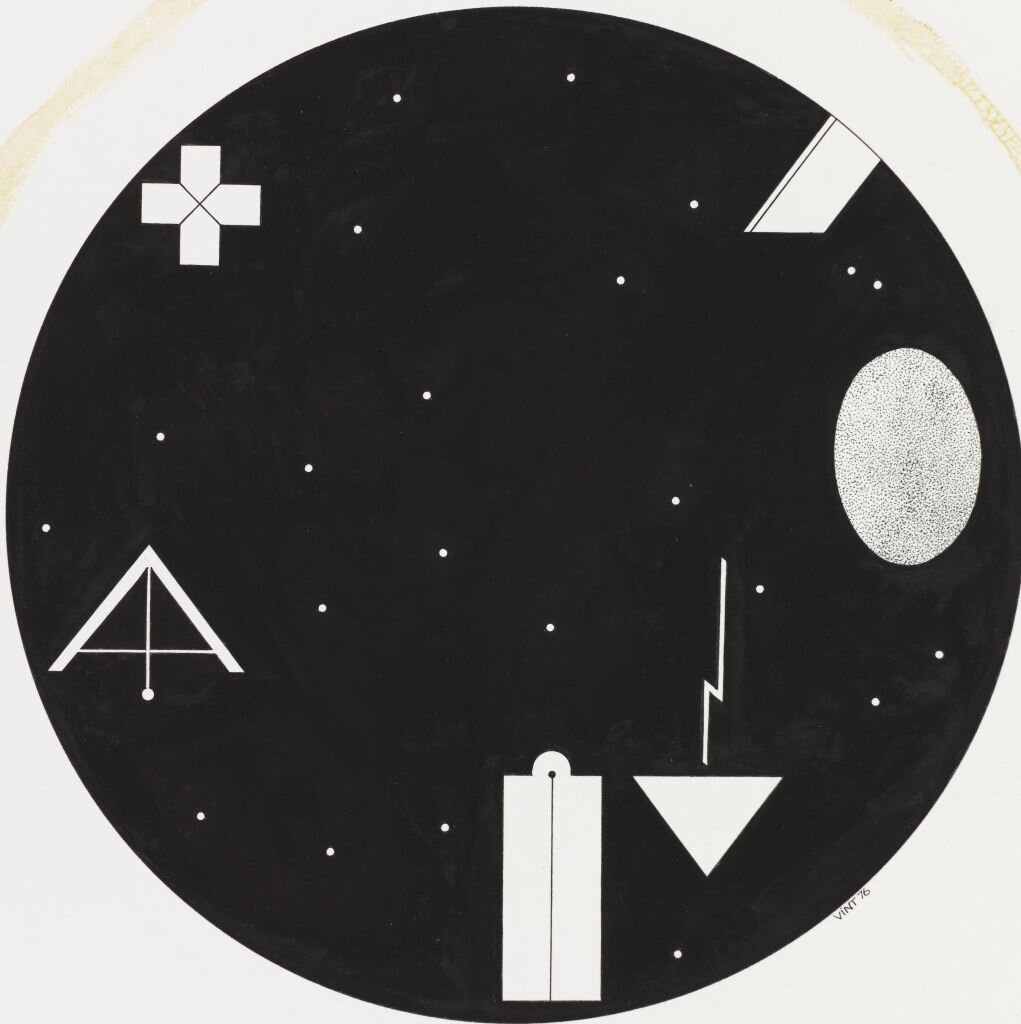

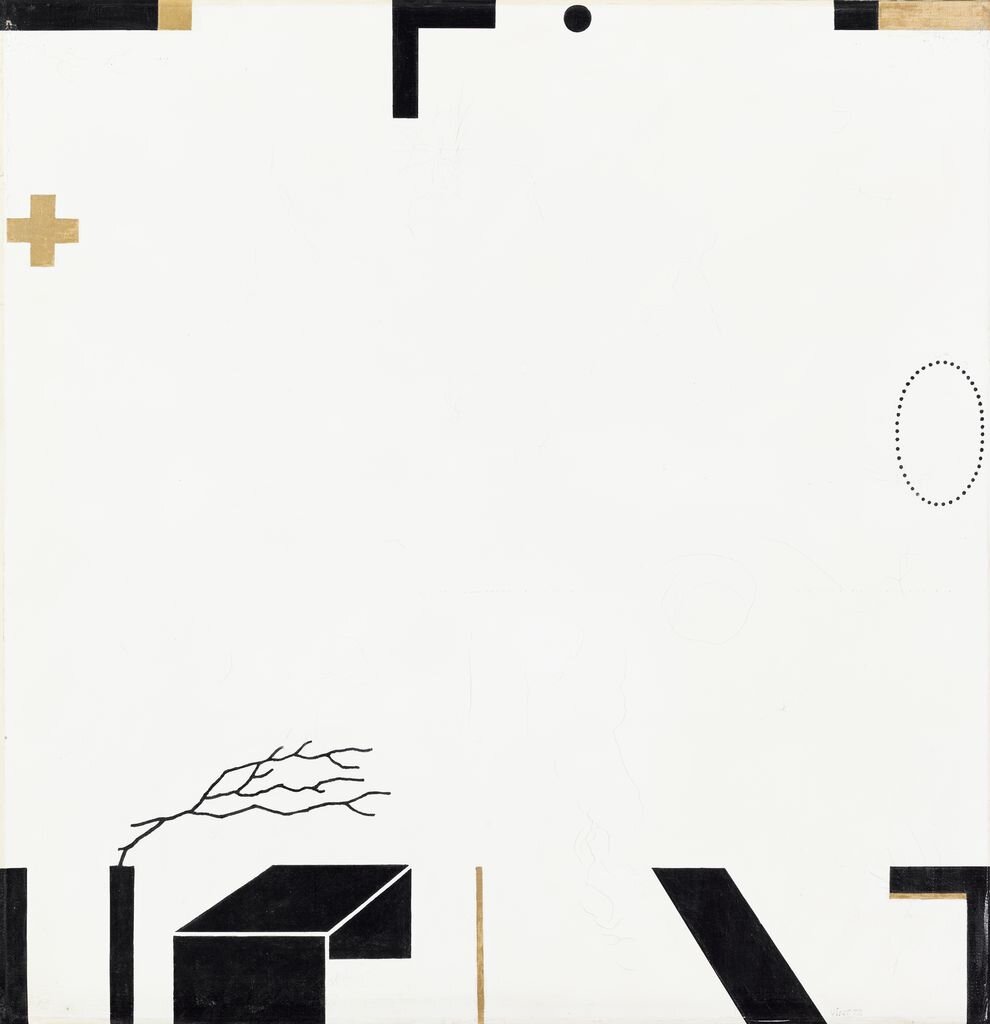

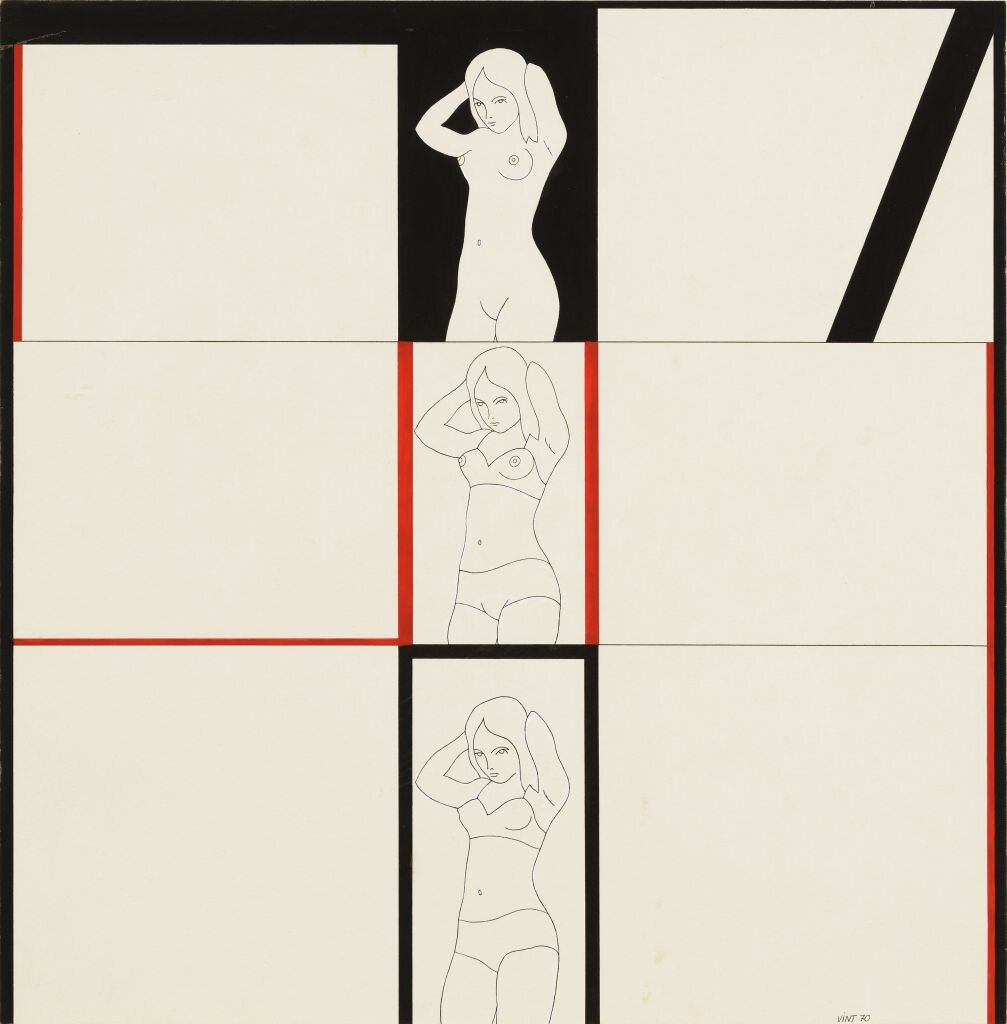

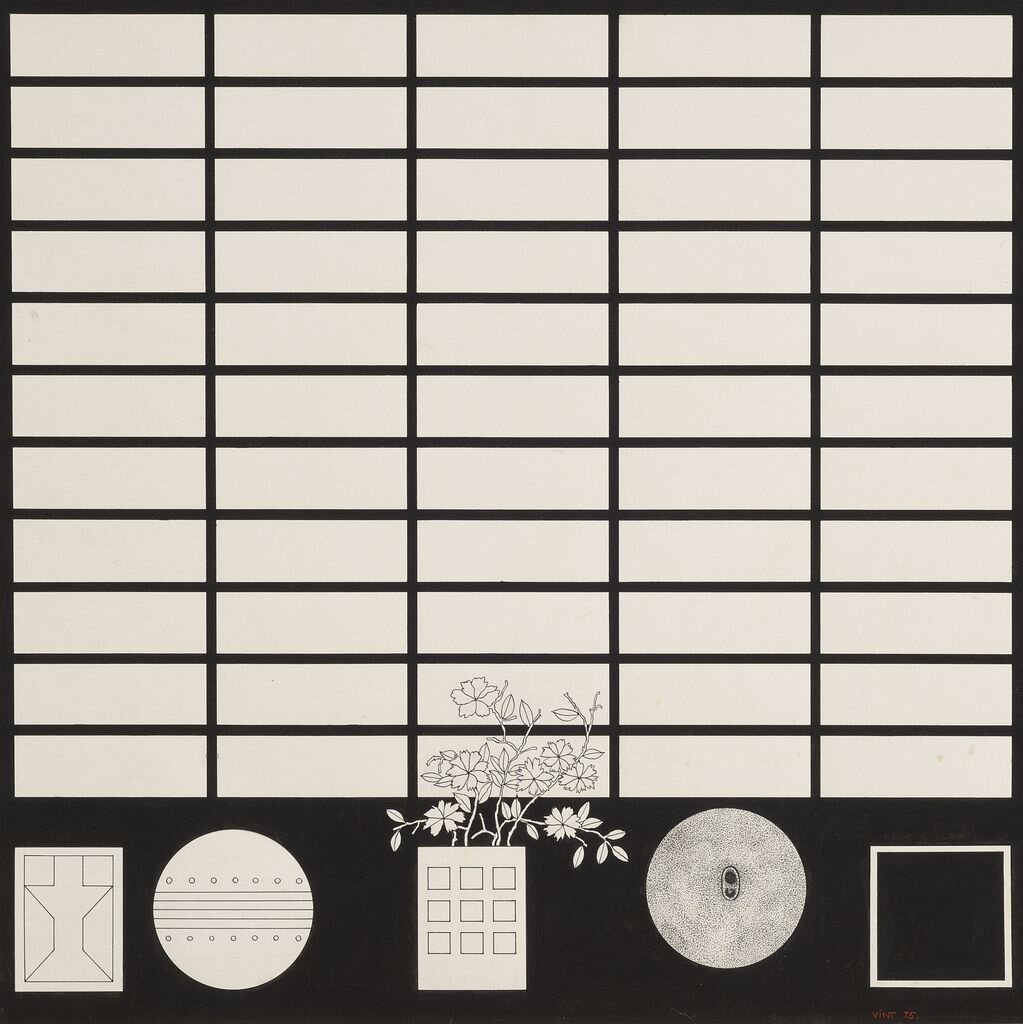

After that, it was possible to get some more relevant artists to exhibit, for example Tõnis Vint was one of the artists that I made an exhibition with. He was an artist strongly related to esoteric knowledge, probably he was the first bright representative of New Age in Estonia. He was interested in New Age, not only in imagery but also in a rhetorical level; he had a type of salon, mainly oriented towards teaching, with endless meetings. He might have been the biggest name from Estonia, and also became popular in Moscow. He worked with graphic designers and made collages, worked with ornaments and such, all Pop Art.

He became interested in geometrical space. And later turned to erotic art. In fact, he was the first person who started to talk about empty space, white empty space that is not really empty, and how to manage this emptiness.

PE: [leafing through a catalogue from the vaults and smiling]

EK: Oops!! [looking on some equivocal imagery] Oh… Yes, yes, always… he had a strong sexual impact…

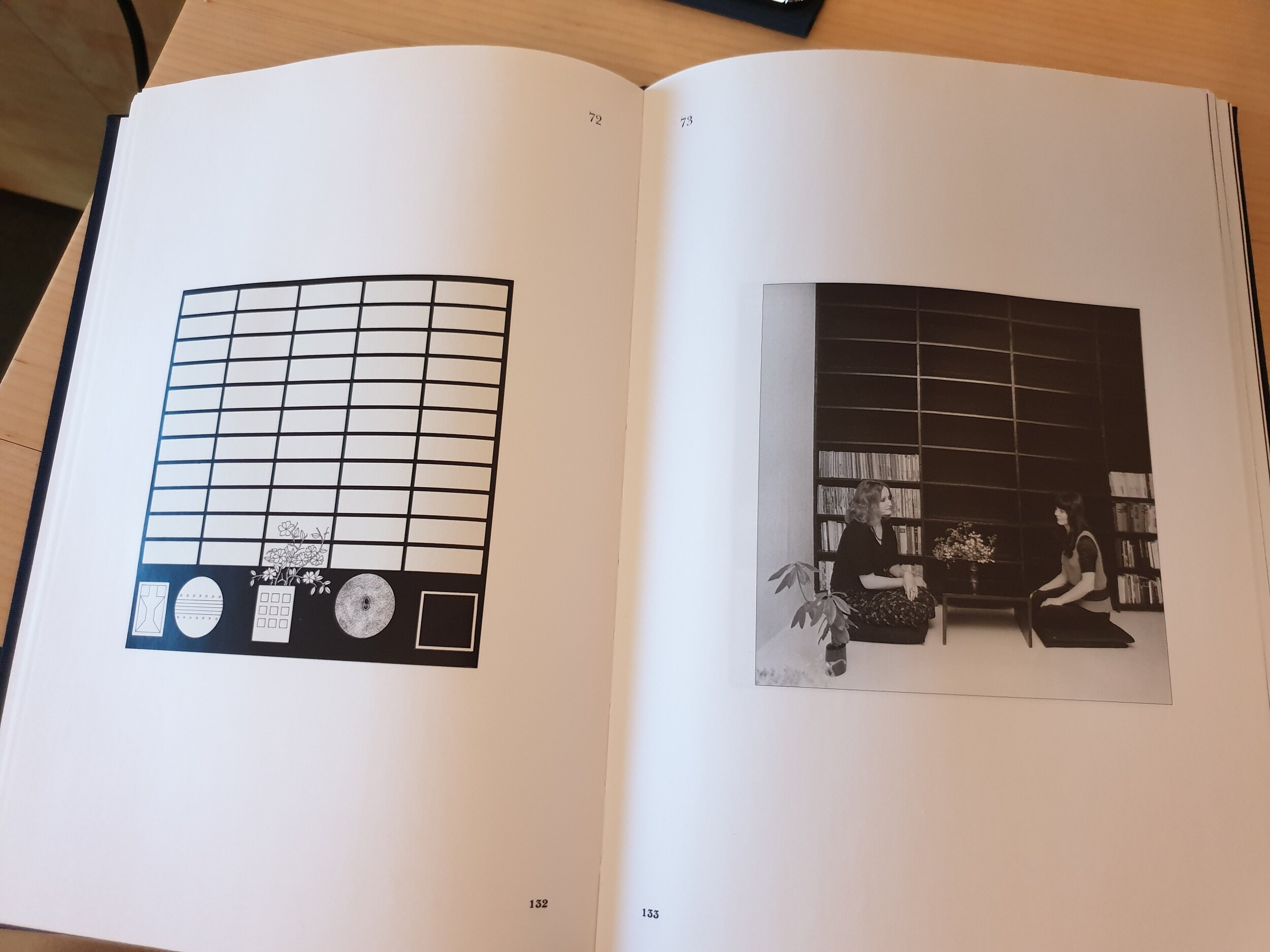

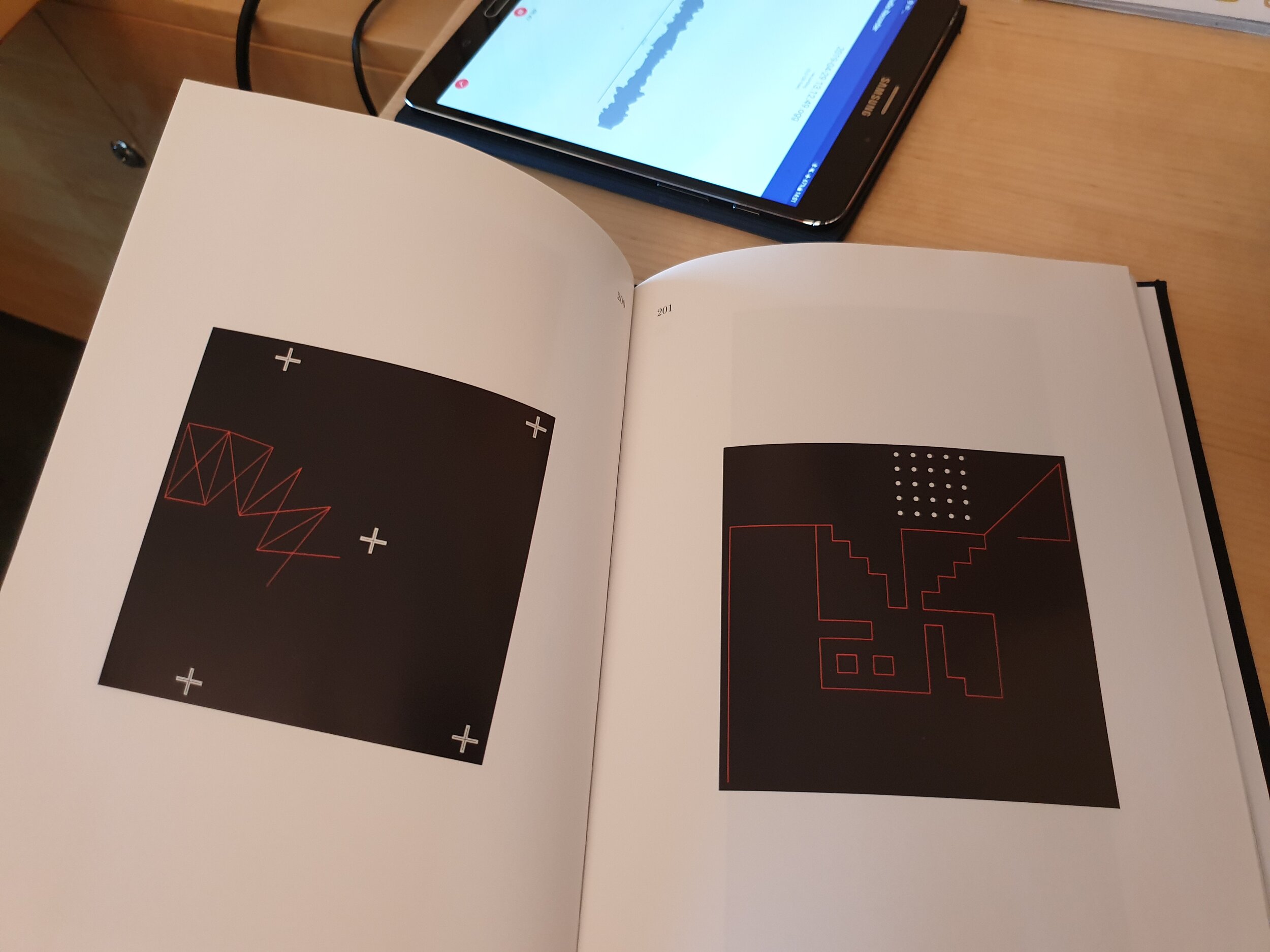

Tõnis Vint (1942-2019) catalogues, and in order: Figure, 1973, Composition III (Magic Landscape A), 1975, Signs in the Night, 1976, White Room. 1972, Morning, 1970, A Japanese Room. Things, 1975.

PE: Ladies… ladies… and more ladies here…

EK: Yes, it is one way to interpret pop culture, you know: sex. Japanese and Chinese symbols had very strong influence to his art too. Here, more girls...

PE: At least some are not naked...

EK: He lives in an empty white space filled with just symmetrical structures and mandalas.

PE: Quite a character! And you made an exhibition with him?

EK: Oh, I wasn’t a curator then, I was just a representative from the museum. But later…

You know, I actually hated New Age! He was a very decadent person. He also said he met with UFO and had conversations and such.

PE: Wow. [laughing] So beautiful, all this [looking in the catalogue]!

EK: Yes, very nice, he was a very original thinker. He learned some cosmic codes, highly cryptic. He was the source of much information that came in to Estonia from abroad, and I appreciated him very much. I myself came from a background of existentialism, so to me New Age had a childish understanding of the world. It had no contrasts and death meant only to become part of the cosmic realm, so it was not for me. But these thoughts were very important for Estonian art during the 80s.

PE: He seems like a crossover between Warhol and the hippie movement.

EK: Yes, a highly sexualized person and inspired by mysticism, but he was too bourgeois to be a hippie.

PE: Was the hippie movement strong here?

EK: Well, people were young, listened to rock music and had long hair, and were labeled as hippies. I heard there were even hippie colonies, but I never saw them. I took part of the culture of flower power, it was nice, but it was early and we didn’t have any details about this lifestyle, and the information about this culture came later. The hippie criticism against the Vietnam war was here interpreted in a very different way. USA could do nothing wrong, and it was so strange that a superpower like USA could lose the Vietnam war. It was a belief in the western life as something that couldn’t be wrong or at fault, a very unfiltered view. I myself met rock singers who had connections with hippie culture, and I was listening to some of that music and had long hair, but that didn’t make me a hippie.

PE: Going back to the topic of curating, you mentioned that you didn’t curate, but that the artists curated themselves.

EK: Even in the 90s, this was still mostly the case.

PE: Yes, I remember the debate about the curator stealing the limelight from the artist in the late 90s, with the rise of the star curators like Hans Ulrich Obrist, or in Sweden for instance Maria Lind...

EK: She is a very powerful curator. Or, I see her rather as an institutional critic than a curator. This topic was a very big topic here in Tallinn in the 90s, all of a sudden all the artists were making art that took a stand against the institution. It became a norm, a rule. “I and my free friends can do much better than any institution”. The institutions were considered dead, finito. Especially museum curators were extremely unpopular.

PE: It must have been a very turbulent time! I want to hear more about this structural change, but I also need to know what happened in the 80s, the change from the assistant of assistants toward becoming a curator.

EK: The first professional curator that I met was Marketta Seppälä, she was a young curator at the Pori Art Museum. She invented the topic of the exhibition, she invited the artists and organized the catalogue of the exhibition and so on. She also refused any compromise with the Artist Union in Tallinn. On top of this, she organized a performance program for the exhibition, and for me that gave me a big impression about how the museums in the west were organized. This was before Kiasma, so Pori Art Museum was at its height and hosted exhibitions with for instance Yoko Ono and stars like that. For me it was such a great impression how easy it was to move artists and to make events and so well integrated into the art system. It was really great.

Very soon after, all changed for Estonia. In 1992 Estonia become an independent country. This meant that all the Russian money were taken out of the country and the stores were completely empty. The Estonian krona came about, and even though the currency didn’t have an international position of course, things started to change again – all of Europe changed too. Liberal capitalism started in such a way you never have seen. You can only dream about it in Sweden. It was very brutal and the process very quick. In only two years maybe, it changed the entire art world. The local art scene had earlier been completely oriented towards the Moscow market, but it didn’t exist anymore. We didn’t have any national state that could buy artworks as it did before, and we didn’t have a gallery system either. That’s when George Soros arrived, with the statement that they were going to support contemporary art.

At this point in Estonia we had very few people, only three or four, who were art historians or worked with art in a more professional way, and had some sort of curatorial vision as well as contacts with the world outside of Estonia. I worked with them and made a few exhibitions for Soros, one in Kadriorg Museum. I gathered only artists that were interesting for me. It was an interim situation as the institution didn’t have any money. I think and hope that I was quite free from what was considered trend within the Soviet Estonian ideas about art. I chose art just recently made, and a lot of performance art.

PE: Performance art is always difficult to exhibit, and it’s also very difficult to document.

EK: The problem of documenting started later. We didn’t have any publishing companies at that time and the museums had all collapsed. On top of that we didn’t have any kind of culture of catalogues since the tradition just before, in the Soviet times, had produced absolutely miserable things. They were oriented towards a certain type of historical view, completely entrenched in a social national classic narrative. And small too.

Besides, the Soviet Union didn’t have enough paper anyway, it was a real problem, there were no factories. All the paper that were produced went into the propaganda machines like Pravda and such.

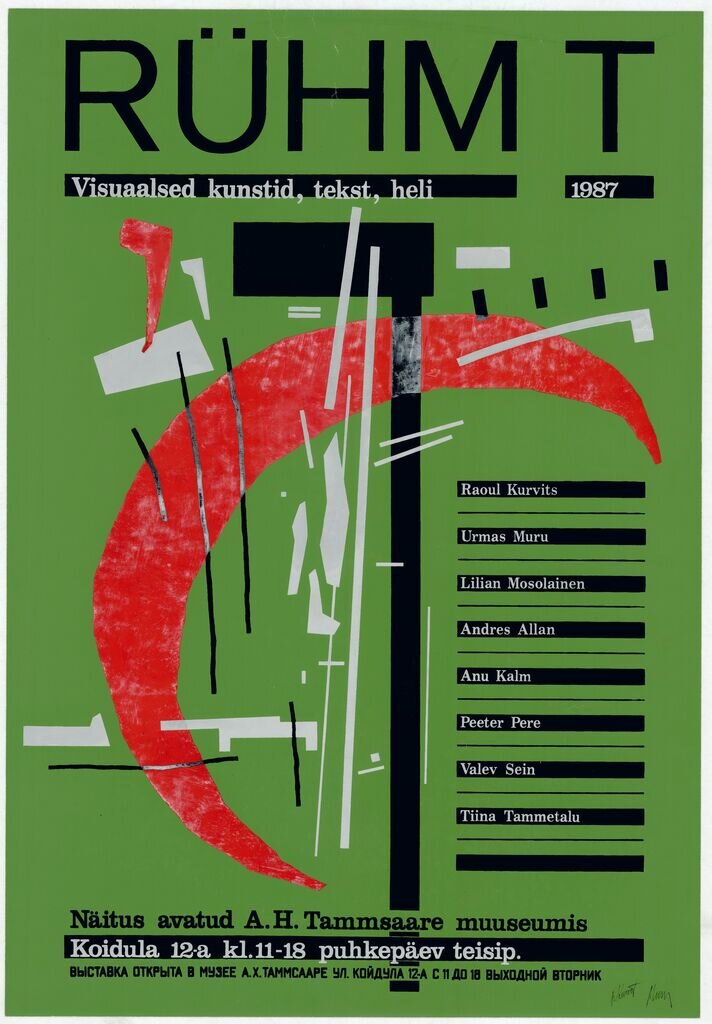

Therefore, we started without catalogues, without education and without knowledge about the art theory, trends or the international discussions surrounding it. The discussions here started with some artists who had some contacts and a sort of feeling, and some ideas of what they wanted to do. For example Group T. It was a very active performance group who also made industrial rock music.

I was in Helsinki with Raoul Kurvitz, one of the leaders of this Group T, consisting of young architects, who had just finished their studies. They were active in performance art and music.

PE: That is unusual, I never heard about any similar thing in Sweden, a group of performance artists, architects as well as musicians…

EK: Ha ha, no of course not, Sweden is such a regulated society...

If you are connected to international art and can travel and function as a member of this network, then you can function as an artist only because you are a member in this network. In Estonia you didn’t have that network. But you really need to create it for yourself, and it is possible to create that if you are interested in many different things, and the most important thing at that time was rock music. In Helsinki, when we were there, Kurvitz went directly to the local radio station and informed them he was an Estonian and that he absolutely loved Einstürzende Neubauten and Kraftwerk. The Finnish persons working at the radio immediately started to make a tremendous amount of pirate CD records overnight for him, so he went back to Estonia carrying suitcases of CDs with a treasure of new music. This music inspired their industrial music performances.

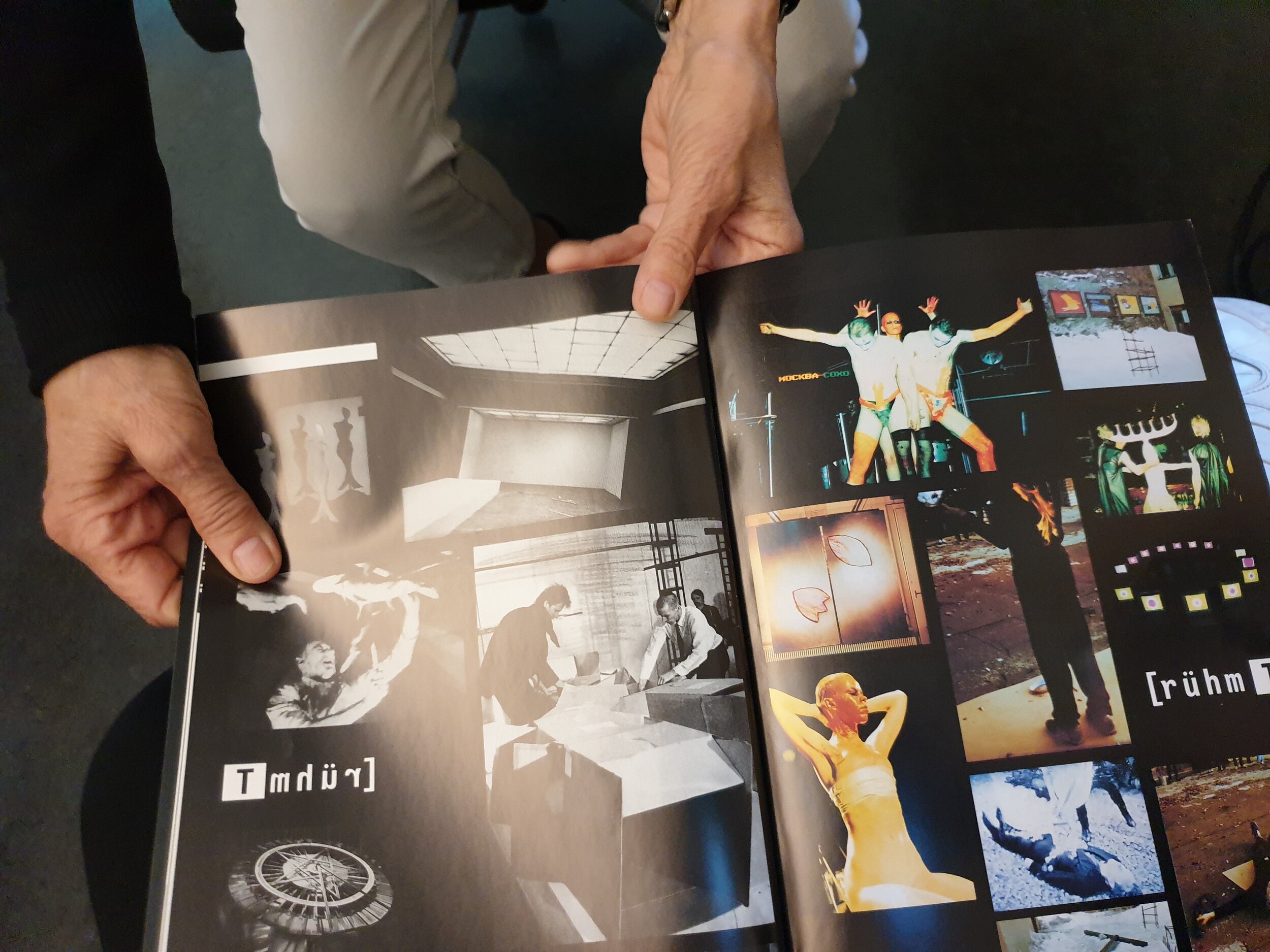

If you really want to make something fantastic and groundbreaking, you must have different artistic points of departure and then try to synthesize this into something. It might not look so original if you look at the imagery today [folding out a catalogue] but the intensity of the performance was amazing, and here in Estonia, and during that time, the early 90s, it was completely new and very different from everything else. They lasted over a long time, and they really helped created new art scene, and were extremely influential.

Most of the artists that came out of this time didn’t make anything like painting or so by hand, instead they were showmen, managers, performance artists and all strongly connected with music.

I knew the group well, but they didn’t need any curator, they were completely self-going, a type of deus ex machina.

PE: But you wrote the catalogue text here in this publication…

EK: Yes as soon as I possibly could I made an exhibition with them, but this was after a long time. The group included an important writer, Hasso Krull, who were writing their own texts, and all their activities were all connected with postmodernism, Deleuzian nomadism etc. In Estonia we at last now have a few translations of Deleuze but at that time we didn’t, so it was a wild interpretation of all this. We have a big Deleuzian impact originating from that time, a very small Foucault impact and then later a very strong feminist movement.

You can’t find any logic in this, but I think that Foucault had too much links to power, the state, the intellectuals, and the archive and whatever, for him to have a larger impact here. For the young people it was not so interesting to hear about this, they had enough, not even the things he wrote about sexuality. But the Deleuzian endless moving nomadism, with no roots, was much more appealing, since Estonians do not have roots either and things are in constant flux.

The first powerful curator was Peeter Linnap. He was a big fan of photo art, and heavily invested in creating a space only for photo, which he considered far more important than any other medium of art.

PE: Was he your colleague?

EK: No. He was absolutely independent. He started the famous Saarema biennal with his partner Eve Kiiler in 1995. It is situated on an island close to the Swedish border. He is the best case study of how institutional critique from here looked like. He is a photographer, researcher and a curator.

He was in contact with international curators and artists, but had a deep hatred for institutions. He became a very central person in Estonia, especially for students, and he is now at the Tartu art school, teaching photography in art. He was a very productive person, writing and such, and was strongly connected with photography as a new form of art and documentation.

I was never connected with this, but I was working five years with Vaal Gallerii. Vaal was big and entirely independent, and the first private gallery in Tallinn. I had a deal with the owners to be able to make exhibitions there, and I could invite whomever I wanted. The space was energetic and lively, we filled the space with all types of art, performance, photography etc., even though photography had in some manner become Linnap’s “belonging”, he was head of the independent photography. First there was him, then there was the Soros gallery and then there was Vaal Gallerii.

But then the Rotermann Salt storage space came about, where the Museum of Architecture is situated now. It was an old salt storage in the harbor, which at that point belonged to the state and there were discussions about turning it into a shopping center. Then there was a radical leftist government that had understood that the Estonian Art Museum didn’t have any space, so they decided to give the house to museums that didn’t have any spaces. They gave the first floor to the Estonian Art Museum, and the second floor to the Museum of Architecture.

The Estonian Art Museum wanted to refuse at first because there were huge windows in the space and it would be impossible to hang paintings on the walls there. As it was half empty, I asked for a meeting with the director and asked him to give the space to me, “I am a curator and I can do great things here”. So this is how it happened, I didn’t get any budget for making exhibitions, but they paid for electricity and so on. This is when I started to work as a curator. I had one technician, one video projector and no ideas of how to run all this.

In 1996/97 I made the first exhibition, where I put together the representatives of the streets, people, situations in Estonia. We had photography, performance, installations etc. in the show, and Linnap hated all this intensely. In his view museums were completely dead structures, and this somehow motivated me even more – I wanted to show that an Estonian institution, the museum – and keep in mind that this was an interim situation when we in a way even didn’t exist, because we were in transition and didn’t have a proper space for our collection – that we can function as a contemporary art museum. It was in some ways very easy because money was invested in Eastern Europe.

For instance British Council liked the Salt Storage very well, they brought me to London and asked me “What kind of exhibitions do you want to make?” I replied “I think we are very uneducated in Estonia and I want to make an exhibition with pop art”. They were taken aback by this since it is very expensive to make such an exhibition and asked if I could make an exhibition with graphic prints by pop artists which is less expensive. This way we brought great swinging London graphic art to Tallinn. The Brits left Estonia very soon and didn’t have any real interest in Estonian art. It was a strange time and a strange request for them.

PE: Why do you think the interest ceased?

EK: No one has any interest any more, neither EU, Sweden, NATO nor America. They poured a lot of funds here, and then withdrew abruptly. The results are terrible, and the situation is bad. It has nothing to do with the art world, but the reason has also to do with the right wing turn that started in Hungary, Poland, and now in Estonia, the populist, halfway fascist, right wing parties that are elected to build governments, in connection with the huge support that came in the 90s and the early 00s from the outside world. It was a very large and very quick “shock therapy” that ended quickly too, and people were supposed to make big things happen by themselves. A part of the people, say, 10-20 percent, do not know how to live in the new system and are only beggars. They lost every qualification, and are asocial. All of Eastern Europe has these asocial people that are called “losers” in big numbers. And now they have found a voice, fascist voices.

This is exactly how it was in the 20s in Germany. They don’t have any possibilities to go to the western markets, no support and cannot find support at home either.

PE: But how did it affect the art?

[Marita Muukkonen enters and everyone says hi to each other]

EK: Contemporary art was always snobbish and outside of all this in a way.

PE: But you are not snobbish!

EK: Of course I am snobbish! Because you have made some decisions in some matters of taste, it of course s becomes snobbish. When the right wing party won in Poland, they gave a lot of money to the local art dance groups and artists that chose to support the party.

Marita Muukkonen: How do you see the situation in Estonia in relation to Poland and Hungary?

EK: It has not gone to the level as in Poland, where they are banning feminist art and artists from institutions, but the right wing has huge support, and our new catholic wing… we never had a catholic wing before, but its’ growing and it’s fighting abortion and feminism here, so things are changing.

MM: Have you already talked about the early feminist wave here?

PE/EK: No, not yet.

MM: Ah you are just warming up, huh? Ha ha.

EK: Yes, yes. We reached only the 90s… and the conflict with Linnap.

PE: How did this conflict unfold, was it in writing or in public talks or…?

EK: It was cultural talks and he was very active, and he sent personal messages to me. I was representing the institution and he was the leading anti-institutional person. He experienced some personal traumas and eventually lost power and momentum in the art world. I’m not saying that I was making very good exhibitions or had especially bright ideas or so, but I worked within the institution and tried to make exhibitions that from my point of view were important.

In Vaal Gallerii I was completely free to do whatever I wanted within three – four exhibitions a year. Mare Tralle made her first feminist exhibition there for instance. During these times I was very motivated by feminism. Later I started to look upon feminism as a more institutional and structural thing, but in the mid 90s when prostitution was absolutely a huge topic. Commonly, in these big industrial rural cities like for instance Narva, where the factories were closed, and lots of families could only stay alive by sending their daughters to Tallinn to become prostitutes.

Lina Siib, Presumed Innocence I, 1997

Tallinn became a very important place for men from the Nordic countries, especially Swedish men. I saw Swedish men in big numbers coming for prostitutes. Finnish too. They came in with helicopters, there were jokes about the important Finnish businessmen coming in from Helsinki in the morning, having two meetings with prostitutes and then going back in the afternoon to their families, it was only a 25-minute helicopter ride.

MM: How was this Est-Fem exhibition received in Estonia? I worked with Mare Tralla, and she talked a lot about this particular exhibition.

EK: I will go find the catalogue, it’s here somewhere [walks away and finds it quickly].

MM: Oh, it’s a beautiful catalogue!

EK: It was in fact received without problems. All the response turned around Tralla. She took on the image of “bad girl” and wrote columns in the newspapers, and from the position of a very bad, ugly, and strange girl with a type of grunge look, and talking about how great women are and men are bad in a rather primitive way. The fact that women’s salaries are so much lower and so on, these were the issues brought up. The level of this project was not easy to get for an audience. At the time Tralla didn’t have any enemies or anything, she was an attractive, beautiful, and exceptional girl who did crazy things so she was absolutely free. It was a strong issue, but Tralla had at this point not yet an articulated social message, but immediately got a lot of attention and was on national television to talk about women’s position in society and so on, so her position quickly become more sharp. Her messages were absolutely great and important, “Second Hand Love” etc.

Concerning feminist issues I had very strict social position, I started to collaborate with Liina Siib and she had a big work, “Presumed Innocence”. In Estonia at that time, if you were a young woman who, let’s say, killed your husband, you would go to prison together with all your children. The prisons looked like strange family facilities with many generations together. Siib made some exceptional photography from the prisons, and also from the unemployment in the streets.

These were bad times to say you were a feminist – it was like a joke. “You are a feminist? Oh then you must be very ugly! You had too many children and you are a loser!”. If you were a feminist, you were a loser in life. Finland had a feminist wave at the time, and their views, upon coming to Estonia, were quite critical. After Katrin Kivima came back to Tallinn, she had studied in Leeds with Griselda Pollock, feminism eventually received a better position. The cultural debate was boosted in a important way by Kivima from 2000 and onwards, she wrote a lot of texts and theory.

Together with Katrin Kivima and Mare Tralla, I stayed in the front with the feminist topic. There are many unresolved social problems in our society, political problems, unemployment in big numbers, and prostitution, we have become a colonial country for rich Scandinavian banks and business men, dirty money laundering and gambling. I believe we need to connect the social structure more closely to feminism.

PE: Did you experience the patriarchy in your work?

EK: I met a great deal of men, so-called geniuses, that never made mistakes in all kinds of positions in the art world, but they were all connected with the older structures. Young artists and curators are not embedded in the patriarchy in the same way the older ones are.

But if I were to try to make a historic exhibition – I do not work with the art history department now, but if I were, and tried to make an exhibition with only female artists, it would be very difficult as we collected only male artists in the collections. The female artists were surrounded by male artists, not as how it was during the Finnish “golden age” for instance, where you found independent female artists. Here it was just powerful men, men, men.

As a curator I have a difficult position if you consider our history, we have only maybe three, four female artists during the past 100 years that were really powerful and had a voice. For example Anu Põder, I knew her very well, but I never put her into a feminist context. She was always absolutely against the feminist political position.

But then Rebeka Põlsdam, a young curator, placed her in the right context. Now Põder is dead, but she became very big, and her discourse is absolutely fantastic. Of course Malle Leis must be mentioned and also a few others that were better than any male artists. However, we need to exhibit our male artists too, of course.

MM: Were there any kind of feminist discourse before Perestroika?

EK: No! Noo! After Perestroika in the 90s, if you asked very good female artists about feminism, they would have said “I don’t appreciate feminism since I am equal with men, and sometimes better than them.” There are also other examples of powerful women that would (still) say that they refuse the position of feminism, and say they are a a type of femme fatal, ready to eat all men, but say “no” to feminism.

I have to say that I don’t understand the conservative motivation today. I don’t understand the rhetoric! And I don’t understand those who say we need to leave the European Union, to be alone and start singing the Estonian National Anthem! I hate this. I was always oriented towards the international art world and I don’t think that one small nation can do something independently.

PE: And still, one reason you have a National Museum at all is because we are formulating a national story. We are somehow stuck in a mythology of nations, with the culture of a nation, or the ideology of a nation etc. How would it be possible to move away from that?

EK: Well, we wouldn’t have any cultural institutions at all if it weren’t for this model of National explanations. It’s a two hundred year old discourse. The discourses of internationalization, globalization or the international art world have been brought up a few times, after the Second World War, or in the early 2000s for instance. Then the topic was hot. But the discourse is so young and so incredible fragile. As soon as there are some problems inside the countries, that type of discourse vanishes immediately. Estonia was very international well into the 2000s, but after the economic crisis this started to change step by step, and populist nationalist parties grew.

MM: Do you feel any pressure from this nationalist discourse that is growing here in Estonia?

EK: Not yet. Not yet. But there are some visible changes over the years, and of course it’s dependent on a type of collective decision. We have more and more started to make conservative exhibitions based on a monographic model, and showing the classics increasingly. Just fifteen years ago we didn’t make exhibitions like this. It is perfectly fine to work with the classics, but it is also very important to try to create exhibitions with new names.

I’m not implying that this change is dependent on any individual person, like the director or so, it is a much more general change. We also have so many new and young people working here as well. It is some other type of general understanding that “all is great, all is fine” which has no concern for the political disagreements and different experiences...

PE: I know you have been working with display of the collection here, and the presentation of the collection. I know that at least once there was a controversy, can you tell us about that?

EK: Yes, it was when KUMU opened in 2006. My opinion was that it was important to display our connection with Soviet Union as part of our history, and to show socialist art within the permanent collection. Some works are very central to our museum. Another idea connected to this, was to make a large overview of the Estonian classics. There was a contemporary art exhibition in the first floor and in the big hall here, and I made the socialist realist permanent exhibition.

Now I understand it was a very big mistake from my side. Like Boris Groys says, and rightly so: it is impossible to make a good exhibition with socialist, Stalinist, social realist art, because it is always oriented towards propaganda and never starts off from a point of criticality.

Anyway, I just put them all together. There was a huge controversy about this, and opposing me was the University, loads of students with critical positionings and so on. It hurts a lot when you are in something like this, absolutely all alone, and even all your colleagues are against you as well. I had no supporters. Even my oldest supporters were against me. It was the worst situation.

And, of course the Nationalist Party hated it deeply too, and the artists hated it as I showed artists who had collaborated, collaborationist artists who are still alive and active. Also young intellectuals who wanted to see more of the opposing positions within the artist groups. Of course they are right. But it turned into a debate where artists wrote long declarations every day in the newspapers about how they fought against the Soviet Union, how they were avant-garde and not collaborationist at all.

Society was not ready for this critical position in the exhibition This historical exhibition was only displayed during one year, and it was rapidly changed. I lost every contact with this exhibition. Now the permanent exhibition is very good, I believe. We have a success story, we have a mix of a little social realism, a little pop art, some avant-garde, and independent Estonian artists. It is like a big map of information. The rooms are now also changed a lot, architecturally. When I made the first exhibition in that space, it was not a good space for art, it was basically too much architecture.

I’m not saying it was a good exhibition, but at that moment, I was very emotionally charged. I took part in a big seminar about East art later on. The only person who liked my show was Piotr Piotrowski, an Eastern Europe art theorist and historian who unfortunately passed away some time ago.

MM: It is a dilemma in Eastern Europe in general when you are dealing with historical exhibitions, how to deal with this period.

EK: All of colleagues told me, even Anda Rottenberg, to never do such a thing again. It is linked to too many people, and too many different moments in history.

MM: It leads to many emotional issues, many of the artists from the Baltic countries went to Moscow to study and it stirs up all kinds of memories. So many connections, so much history.

EK: Absolutely! But I am still not happy with this sterilized, aestheticized historical view that is now trending everywhere, and especially in Moscow. The way they are only showing dissident art, I think that’s amoral. You are suppressing the Eastern Europe and how it was. Now they are all presented as freedom fighters. It is part of a political trend of course.

Afterwards I tried to reflect on what I did wrong, where and how. I was very sentimental. I really wanted to open up for the tragedy of this country’s art: how terrible it was to work as an artist in totalitarian times. I wanted to build a model of totalitarian art. But I couldn’t do it, because it clashed with this nation’s sentiments about what its national identity is. It was very difficult.

MM: You did this also quite early on after Estonia gained independence, as far as I remember, all these oppositional characters were all anti-Soviet and I can imagine it was very emotional.

EK: I showed them every position of that time you know, if I had only showed socialist realist artists it would have been one thing. But I showed the avant-garde as well. I was myself connected to Estonian modernism. In the 60s Estonian modernism was phenomenal. They attempted to stay outside of the harsh style of Moscow and build up a modernist discourse, and tried to get information about modernism, independent views about it. But in this moment Estonia is still connected to Postmodernism. Modernism is left out, and I tried to show it.

I just wanted to show history as it was, you know.

In February 2021, Eha Kommisarov was awarded the Cultural Lifetime Achievement Award in Estonia.

Marita Muukkonen, Co-Founding Co-Director of Perpetuum Mobile (PM), is an internationally active curator based in Helsinki.

All images of Eha in action lent, with permission, from the instagram feed of Kati Ilves, curator at KUMU. Other images, without caption, taken by Power Ekroth at the time of the interview.

The interview was done with help from Nordisk Kulturfond