A Form That Thinks: Knowledge Through Montage in Georges Didi-Huberman

Kim West

Cinema was the true art of montage that began five or six centuries BC in the West. It’s the entire history of the West.

Jean-Luc Godard

“It is probable that interesting history is only to be found in montage, the rhythmic play, the contradance of chronologies and anachronisms,” Georges Didi-Huberman writes in Devant le temps, one of his examinations of the fundamental philosophical concepts of art history.1 Earlier on in the same text Didi-Huberman returns to one of his favorite examples, a “pan” of color onto which bright splashes of paint have been applied, in a fresco by the Renaissance painter Fra Angelico.2 He places us directly in front of this surface: “We are before the pan as before a complex time-object, an impure time: an extraordinary montage of heterogeneous times which form anachronisms.” 3 “The exposition by montage,” Didi-Huberman writes almost a decade later, in one of his latest books, on Brecht, “renounces beforehand all claims to global comprehension.” “Its political value,” he continues, “is consequently more modest and more radical at the same time, since it is more experimental: it would, strictly speaking, consist in taking a position towards the real precisely by modifying, in a critical manner, the respective positions of things, discourses, and images.”4

The three quotes discuss the same concept — montage — but they do so in different ways and as if it denoted different types of objects. In the first quote, montage is the dynamic form, the “rhythmic play,” the “contradance of chronologies and anachronisms” with which history — here understood as historiography, as narrative concerning historical events — can be “interesting.” In the second quote we are placed in front of a “pan” in a fresco which presents itself as a “complex time-object”: the montage is the image as such, which itself assembles “heterogeneous times.” And in the third quote, montage is rather a critical, political method which makes it possible to “take a position” towards the real by modifying and rearranging “the respective positions of things, discourses, and images.” Montage is an image, a historiographic form, a critical method: it has different modes of existence and purposes, it belongs to different fields, disciplines, and contexts.

This swift juxtaposition of partly overlapping, partly incongruent quotes about montage does not aim to reveal conceptual inconsistencies or contradictions committed by their author. Its purpose, rather, is to indicate the reach of the notion of montage that is operative in his texts, in order to see if it could be understood as a challenge. Can it today — this is one way of posing the question — be relevant to revive the idea that, in a remarkable manner, spread among and fascinated artists, filmmakers, and philosophers during the period between the wars: the idea of montage as the paradigm for a general project of cultural critique? In a series of studies published between 1995 and today, Didi-Huberman has turned to the central figures of this project — “the masters of montage,” as he calls them in Images In Spite of All: “Warburg, Eisenstein, Benjamin, Bataille”5 — and there examined montage from different perspectives. He has studied it as a means of revealing “formless” resemblances, in Sergei Eisenstein, Georges Bataille, and the editors of Documents (La ressemblance informe, 1995); as a historico-philosophical method with a specific, redemptive force, in Walter Benjamin (Devant le temps, 2000); as a historiographic technique with the capacity to give access to the “unconscious” of art history, in Aby Warburg (L’image survivante, 2002); and as a critical instrument with the ability to disclose the heterogeneous complexity of the historical moment, in Bertolt Brecht (Quand les images prennent position, 2009). He has also discussed some of the great montage projects of the more recent history of cinema: Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma (in the polemical Images In Spite of All, 2003), and Pasolini’s images of the people (in Survivance des lucioles, 2009, as well as in a series of articles destined for an announced book on “les peuples exposés”). The “montage” that Didi-Huberman has found in these studies is not only a material, aesthetic technique for combining images and texts, but also an abstract form of knowledge which seems to question the very notion of history as a linear evolution, in which phenomena can “die” in order then to be “reborn.”

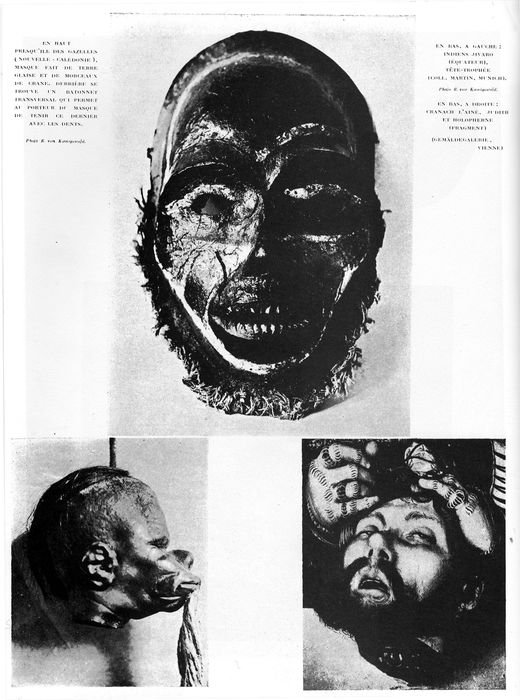

Ethnographic photographs and a detail from Cranach’s Judith and Holofernes. Picture-pages illustrating the article by Ralph von Königswald “Têtes et crânes”, Documents II/6, 1930

Is there — this is another, more direct way of formulating the question — a theory of the montage in Didi-Huberman? Does the concept have a coherent significance in his different texts, despite its plurality of uses? Can we find a description of its nature and purpose, its qualities and capacities, its theoretical conditions and historical context, or its material prerequisites and possible fields of application?

Before we can address questions such as these, however, we must pose another: against which background does Didi-Huberman take an interest in montage? On a very general level we could say that Didi-Huberman’s art historical and philosophical project aims to open up the idea of the image — probably the single most recurring word in his work, which he prefers in its generality to terms that designate specific artistic media or techniques — to time. “Always, in front of the image, we are in front of time,” proclaims the first sentence in Devant le temps, which together with the earlier Devant l’image, in English as Confronting Images, and the voluminous Warburg study L’image survivante constitute the foundations of his theoretical construction.6 However, when Didi-Huberman says that in front of the image, we are in front of time, this does not primarily mean that he is interested in the phenomenology and the time-consciousness of the aesthetic experience, but rather that he opposes himself to a certain fundamental notion about the nature of art history — where “art history” is understood as both historical events and historiographic narrative. In the founding figures of the discipline of art history — primarily Panofsky and his ancestors (Vasari, Winckelmann) and heirs (Gombrich, Baxandall) — Didi-Huberman finds the common idea that the task of art history is to clarify and account for how artworks were conceived and experienced in “their own” time, that is, in the age or historical moment in which they were created. In order to understand a historical artwork, decipher its iconographic play of signs and uncover its iconological layers of significance, one must study its contemporary sources: identify its characteristic traits in the history of styles; compare it to existing documents on the life of the artist; situate it in its social, technological, and ideological context; trace its correspondences with the religious and philosophical ideas of the time, and so on. The underlying, implicit notion here is that on a superficial (iconographic) level the artwork is characterized by a direct legibility, a sort of semiotic self-presence, at the same time as it, on a deeper (iconological) level is embedded within its own now, within the historical, spiritual context — the Kunstwollen, the Weltanschauung — in which it lives (and outside of which it therefore cannot live — but perhaps be revived). The cardinal sin of the art historian would, according to this belief, be the anachronism: to read concepts and stories from another time into the motif of the artwork, to project contemporary values and ideas onto the cultural creations of the past or judge contemporary methods and techniques according to obsolete measures.7

In opposition to this Didi-Huberman suggests a radical reevaluation of the anachronism. “Traditional,” Panofskian art history — this would be another way of putting it — finds its basic model for thinking the relationship between the image and the gaze in a Neo-Kantian epistemology that attempts to chart how the subject “projects” its schemes onto the things, and that thereby wants to render possible a critical description of the conditions for the object’s true presence before perception. In the discipline of art history, this would correspond to a critical awareness of the ways in which the historian projects the concepts and ideas of her own time onto the artworks of the past. Against this critical project, which ultimately strives for the uncovering of a “pure” perception of the historical object, Didi-Huberman opposes a belief according to which both the gaze and the image are always already contaminated, impure, constituted by heterogeneous temporalities and inassimilable differences. He finds the model for this belief — and here one can see a very clear, almost systematic continuity in his work, from the dissertation on the images of hysteria at Charcot’s La Salpetrière in 1982 to the latest texts on Brecht and Pasolini from 2009 — in Freudian psychoanalysis, where the gaze is directed towards dreams and symptoms that mix times and histories, that are characterized by constitutive repressions and productive returns. It is in fact, Didi-Huberman claims, never sufficient to limit oneself to the concepts, theories, and histories that belong to the artwork’s “own” age if one is to understand its actual effects and its ways of negotiating its art historical lines of descent. An artwork is never self-present as a directly legible surface, but torn apart, characterized by becoming and different modes of existence, different ways of acting upon the perception of the viewer. And an artwork never fully coincides with its own present, but is traversed by untimely, surviving forms which force the art historian to question the limits of her discipline and complicate her historico-philosophical diagram: motifs and styles can originate from distant times and places which in themselves appear to set each chronology out of play; essential characteristics of the image can become visible first before a gaze informed by obsolete or contemporary — untimely, anachronistic — methods and techniques, a gaze that consequently may be able to see past this image’s “attachment” to a certain epoch in the history of styles.

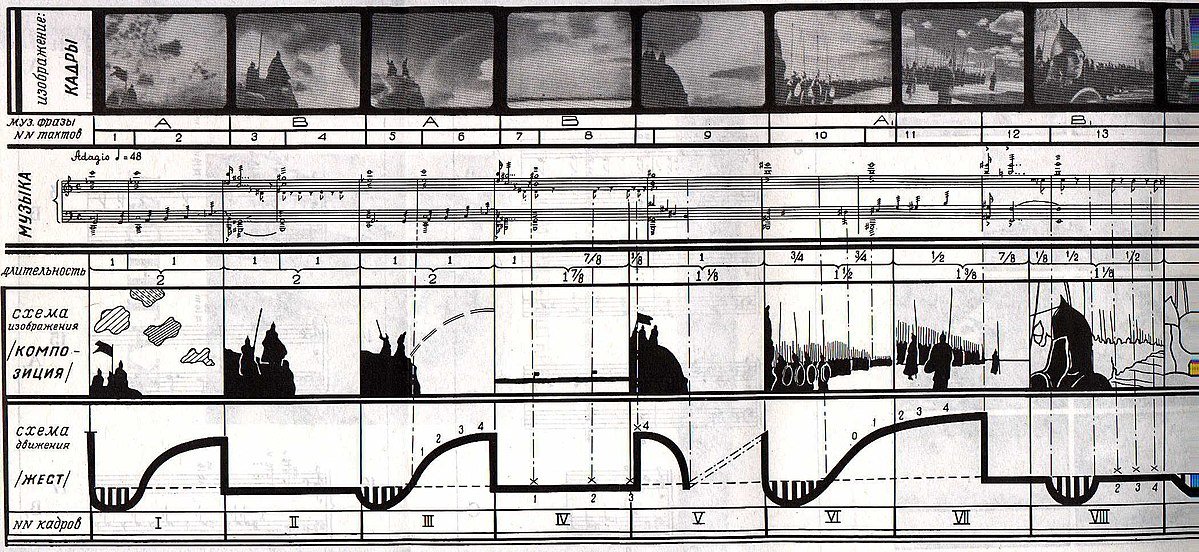

Sergei Eisenstein, Vertical Montage, 1940

Didi-Huberman opens the idea of the image towards time. Against the “monogram-image,” which would be directly legible and correspond to the age of its creation, he opposes a “symptom-image,” which aggregates a multiplicity of temporalities and contradicts simple legibility, and whose art historical description presupposes chronological leaps and anachronisms.8 This, we could perhaps say, has two general consequences for Didi-Huberman’s project, it points to two separate but overlapping problems in his different studies. On the one hand, it points to his interest for the phenomena and techniques of “figuration,” “incarnation,” and “imprint” in Western art history. In a long series of works — from La Peinture incarnée and the book on Fra Angelico to Ouvrir Vénus and L’image ouverte — Didi-Huberman has examined how, in Christian art, there may be a power of “figuration” and “incarnation” that transgresses the statically figurative and mimetic, surpasses the representational system of the image and can instead contain becomings, “pans,” and intensities that act directly upon the body of the spectator. He has also given great attention to the different techniques of “imprint” — molds, masks, prints, inscriptions, indexes — in Western art, starting from which it becomes possible to think the problem of depiction beyond the tradition of mimetic categories, and find new ways of delimiting art’s sphere of experience against other practices and institutions. To write the history of the imprint — this was the starting point for the big exhibition L’empreinte, curated by Didi-Huberman at the Centre Pompidou in 1997, and whose substantial catalogue has later been reprinted as La ressemblance par contact — would therefore imply rethinking a number of the different narratives and definitions that direct the understanding of Western art history as such. On the other hand, the complex temporality of the symptom-image points to Didi- Huberman’s interest in montage’s assemblage of elements, and to the different studies of “the masters of montage” he has undertaken since the mid-90s.

One could talk of three general ways, three levels on which Didi-Huberman discusses montage in his works. To begin with, there is an abstract or metaphorical way, where “montage” does not only refer to the artistic technique of combining aesthetic elements, but also describes a condition — for objects, images, texts, artworks, thought processes, events — which is characterized by a specific type of heterogeneity and temporality. In Devant le temps the “pan” in the Renaissance painting becomes “an extraordinary montage of heterogeneous times which form anachronisms,” and memory “an impure aggregate, [a] — non-‘historic’ — montage of time,” while the images “dismantle history” and consist of “montages of different temporalities, symptoms which tear apart the normal order of things.”9 In Images In Spite of All, Didi-Huberman goes even further and speaks, in a passage with vast implications — which he has not followed up since then, at least not literally — of “a notion of montage which would be for the field of images what the signifying differentiation was for the field of language according to the Post-Saussurean conception.”10 The generality and the reach of this use of the montage concept suggest that it could correspond to some of film history’s “expanded” montage theories — where the most apparent example would be Eisenstein’s notion, according to which “the montage principle in films is only a sectional application of the montage principle in general, a principle which, if fully understood, passes far beyond the limits of splicing bits of film together.”11 In a famous passage in the text from which this quote originates — also known as “Montage 1938” — Eisenstein puts his “general montage principle” to the test in a discussion about a text by Leonardo Da Vinci, in which the Renaissance artist describes an unrealized painting of the Deluge as if it consisted of a carefully orchestrated sequence of events and scenes: the dark sky storms, cliffs crash into the great river, panicking masses try to save themselves on home-made boats and rafts, mothers lament their drowned sons, others take their own lives in hopelessness and despair, animals crowd upon the mountain tops… This text, Eisenstein argues, follows the principle of montage, not only because it seems to describe both a spatial and temporal composition of separate scenes, but also because it, through the movement it traces between the different elements, directs the attention of the spectator in a way that enhances the drama of the composition and “pulls her into” the creative act itself, making her a co-creator of the image.12

Didi-Huberman’s notion of the image as a montage of heterogeneous times, of course, differs in essential ways from this one. In Eisenstein, Leonardo’s text-image is a montage because it clearly consists of a multiplicity of separate parts, which are combined according to a dramatic logic. It is a “shooting-script” avant la lettre, Eisenstein says, and it facilitates the spectator’s empathy and identification with the events of the narrative, and her “fusion” with the artist’s intention. When Didi-Huberman talks of the “pan” — in a fresco by Fra Angelico or a painting by Vermeer — as a montage, this means, on the contrary, that it resists all translation and subsumption into a simple story: segments of the image withdraw from all figurative logic for the benefit of a physical, plastic mode of existence; they resist being seen as details or components of a general composition, under- mining, rather, the order of the image; and they set the categories with which one normally approaches the artists and epochs in question out of play, enforcing a reconsideration of the past’s relationship to its own past and to the present. Consequently, they do not imply the spectator’s empathy or identification with the image’s story and the artist’s intention, but rather force the spectator to question her own notion of the past and her own historical iden- tity. The model for Didi-Huberman’s concept of the montage, then, is not in the first hand to be found in a general montage principle such as the one expressed in “Montage 1938.” Rather, one finds it in Benjamin’s famous formulations regarding the “dialectical image,” which Didi-Huberman discusses at length in the chapter on Benjamin’s philosophy of history in Devant le temps — a chapter that also includes one of his most important arguments about montage as a mode of knowledge. “It is not,” Benjamin says in an often cited passage in the Arcades Project, “that what is past casts its light on what is present, or what is present its light on what is past; rather, image is that wherein what has been comes together in a flash with the now to form a constellation. Image is dialectics at a standstill.”13 “In front of an image,” Didi-Huberman writes, “the present never ceases to reconfigure itself, lest the dispossession of the gaze has completely yielded its place to the self-gratifying habits of the ’specialist’. In front of an image […], the past at the same time never ceases to reconfigure itself, since this image only becomes thinkable within a construction of memory, if not of dread.”14

What complicates matters is that “montage” in Didi-Huberman is not only the name of the pan, the image or the historical object which constitutes a “dialectical image,” but also refers to the procedure with which this dialectical image is produced. There is, one could say, a general sliding in the use of the montage concept in Devant le temps. On the one hand, Didi- Huberman talks of the “pan” and the image as montages, as phenomena that demand a mutual reconfiguration of the present and the past: dialectical images. On the other hand, he also, in direct connection to this first use of the concept, refers to montage as a narratological and historiographic operation, as the principle of composition at the basis for the Arcades Project’s great aggregate of quotes and text passages. An image can be a montage, a combination of images can be a montage. How should one understand this? The image “dismantles history,” Didi-Huberman claims. That is, it is characterized by a heterogeneity that as such opposes itself to a certain type of historical narrative and discloses its limitations. But, he continues, the image only has this capacity to dismantle history — is only a montage in the first sense — to the extent that it belongs to a montage in the second sense: an assemblage of images — to the extent this “demontage” will lead to a “remontage,” a new type of historiographic or narrative composition. In other words, the montage is a double operation: it combines, but in order to combine it must first break apart. “[T]he montage as procedure,” Didi- Huberman writes in the text on Benjamin, “in effect presupposes the demontage, the previous dissociation of that which it constructs.”15 The same idea — the same dialectics — one finds five years earlier in the book on Bataille (that Didi- Huberman here rather refers to the concept of collage makes no essential difference): “How can one not see that only that which has first been separated, cut apart, will stick together [colle] with force? That only that which has first been in touch will separate and ‘cut through’ [tranche] intensely?”16 “Montage,” therefore, is the name of the objects of historical knowledge, of the procedure which assembles these objects into a new composition, and of the form which is the result of this procedure; montage is a procedure which consists in dismantling in order, then, to be able to remount, which in turn generates the montage’s new totality. One could hazard to establish that it is this simultaneous presence on a multiplicity of levels of significance, this at times intractable polysemy, which is at the basis of Didi-Huberman’s abstract and metaphorical way of using the montage concept, where it can denote images and compositions, but also historical objects, intellectual procedures, and methods of knowledge. We could also note that the tension which here becomes visible — between montage’s dismantling, separating, analytic force, and its remounting, assembling, synthetic force — points towards Didi-Huberman’s two other uses of this concept: one theoretical or philosophical, and one historiographic or critical.

In a number of contexts Didi-Huberman returns to the idea that the montage is the means — or perhaps even the medium — for a specific type of knowledge. Throughout his different studies on the “masters of montage” — not only on Benjamin, but also on Bataille and Warburg, and to a certain extent on Godard — an image appears of montage as “theoretical,” in the original sense of the word: it allows for a specific seeing, it renders visible a certain type of qualities in phenomena or in history as such. “Montage,” Didi-Huberman writes in the book on Warburg, “is not the factual creation of a temporal continuity starting from discontinuous ’shots’ assembled into sequences. It is, on the contrary, a way of visually unfolding the discontinuities of time at work in each sequence of history.”17 In La ressemblence informe, the formulation is: “They both” — Bataille and Eisenstein, respectively the editor and the one-time contributor to the magazine Documents — “saw in montage […] the royal path for making the forms regard us, that is, correspond to this ‘essential and violent state of things’ which Bataille would name ‘transgressive’, while Eisenstein would call it ‘revolutionary’.”18 Montage can visually “unfold,” disclose, and render visible the discontinuities operative in each sequence in history. And it functions as the main method for making “the forms regard us,” for opening a specific seeing, before which the things show themselves in their “essential and violent state.”

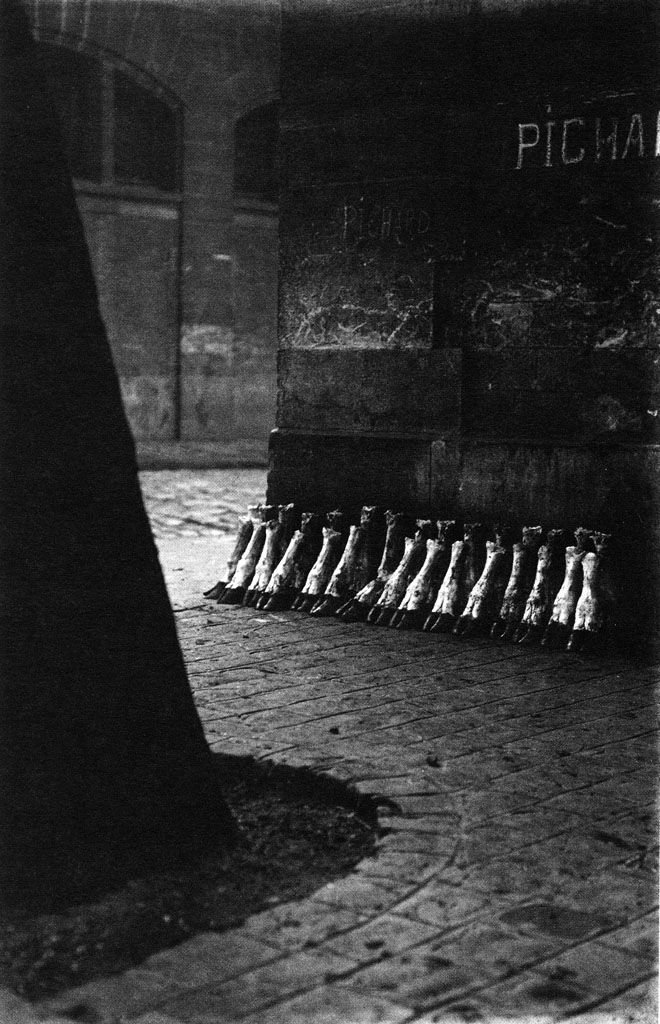

Eli Lotar, Aux abattoirs de la Villette. Article “Abattoir,” in Documents, no. 6, 1929

In La ressemblance informe, Didi-Huberman approaches the concept of montage through an examination of Bataille’s philosophical project and its specific implementation in the art review — in a wide sense, the subtitle was “doctrines, archéologie, beaux-arts, éthnographie” — that he, during a few years around 1930, directed together with Michel Leiris, Georges-Henri Rivière, and Carl Einstein. If the general project of the magazine was to — in Bataille’s terms — establish a cultural theory of “base materialism,” a reflection into the “formless” nature of the human, an “anthropology of cruelty,” then the editors aimed for this both by publishing texts that directly addressed relevant themes, phenomena, and concepts (slaughterhouses, sacrificial rites, cannibalism, insects, body parts, “primitive art,” transgressive literature, etc.), and through an original way of working with images, where the reproduced photographs, etchings, and artworks did not always have an illustrative function, but could just as well follow the logic of surrealist experiments (extreme close-ups, unexpected angles and frames, “graphic” or violent motifs, naivism and exoticism, etc.). By treating the journal as the space for a montage work, where these images, articles, subjects, and motifs functioned as the elements of a macro-composition with its own, specific effects of significance, Bataille and the editors — this is the argument which Didi-Huberman develops in some detail in his substantial reading — expose “resemblances” and “dissemblances” of a type that was foreign to the idealism of Western metaphysics. The principle for the compositional work was, according to Didi-Huberman, a “dialectics of attraction and conflict,” whose model Bataille is supposed to have found in Eisenstein — but not the Eisenstein who in 1938 spoke of a “general montage principle,” rather the one who, ten years earlier, formulated the idea of an “intellectual montage” — a “conflict-juxtaposition of accompanying intellectual affects,” as he calls it in “Methods of Montage” from 1930 — and put it to the test in films such as Strike and October.19 The ability — at least theoretically — of this intellectual montage to assemble separate elements without reducing their heterogeneity, to withhold a relationship of tension between the included parts that emphasizes rather than conceals their differences and specificities, made it the appropriate method with which the Documents editors strove to reveal forces and intensities which were, per definition, inaccessible to the categories of Platonic and Christian thinking, to the notions of “form” and “resemblance” that guided the Western gaze: the states where the human face is distorted and becomes animal, where the anthropomorphic is deformed and deconstructed by being set in contact with the inanimate, with masks and figures, where “cruel resemblances” are disclosed between plants and body parts — and so on. Here, the montage becomes a philosophical form, which can display, make visible a certain type of phenomena and relations: it sets a “symptomal” rather than synthesizing dialectics to work, it exposes differences by establishing connections, it tears resemblances apart by creating them — and thereby it can represent this “essential state” where forms may “regard us” and show their “violent” and “transgressive” nature.20 “Montage,” Didi-Huberman writes in his discussion on Histoire(s) du cinéma in Images In Spite of All, “is the art of producing this form that thinks.”21

Eli Lotar, Aux abattoirs de la Villette. Article “Abattoir,” in Documents, no. 6, 1929

Montage as a “thinking form” and a dialectics without synthesis, a dialectics which does not unite but proliferates, also returns in L’image survivante, Didi-Huberman’s reading of Aby Warburg’s art historical project and of the famous montage of images with which the German art historian worked during his final years, Mnemosyne Atlas. Here too, montage is seen as a method or form which can render other relations and phenomena visible. Here, however, it is no longer a question of the formless resemblances of a base materialism (even though one can find a number of parallels between Warburg and Bataille, notably starting from their respective readings of Nietzsche), but rather, Didi-Huberman says, of exposing “the images’ memories,” of establishing a “rhythm” which discloses the “returns” and the “surprises” in the “long durations” of culture, and which thereby “unfolds” the discontinuities which are operative in history.22 The 63 black screens with about 2,000 photographs that together form the great composition of the Mnemosyne Atlas (in its presently existing condition)23 in a certain sense therefore constitute an application of the historico-philosophical and historiographic concepts with which Warburg wanted to rethink the basic categories of art history and extend its field.

Aby Warburg: Bilderatlas Mnemosyne – the Original, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, 2020, installation view

In order to understand the relationship of the Renaissance to its past it is not sufficient, he held, to accept the classical notions about the eternal life of antiquity or its perpetual and tragically incomplete rebirth — it is obviously significant that Didi-Huberman opens L’image survivante by delimiting Warburg’s project against Vasari and Winckelmann — but rather, one must educate a perception and a sensibility for how artistic forms, styles, motifs, and gestures may “survive” or “live on” (Nachleben) even beyond “their epochs,” by being replaced, transferred, or by migrating to other cultural and social contexts. One must also develop methods for visualizing and charting the patterns, what Warburg called the Pathosformeln for these cross-disciplinary and transhistorical movements, through which styles and motifs travel through the ages and over spatial distances and cultural borders. Warburg’s project, therefore, not only points to an extension of the discipline of art history towards a general science of culture, where anthropological, ethnographic, and sociological investigations become essential for an understanding of the legacies and traditions of artworks and artistic expressions, but also — this, at least, is Didi-Huberman’s central argument in his text — to an affinity with Freud, where images have memories that are characterized by heterogeneous temporalities, even an unconscious, with constitutive repressions and anachronistic, creative returns (and thereby it also becomes evident why art history must always return to Warburg, just as psychoanalysis always returns to Freud — see here Jonas (J) Magnusson’s text in the present issue). Mnemosyne Atlas’s montage of photographs, Didi-Huberman explains, is precisely an attempt to open such a perception and develop such a method. With Mnemosyne, Warburg wanted to design a new type of “comparatism,” which would not search for the common, the unity between the compared terms, but to expose them in their complexity, in order to be able to trace the movements of the “phantom lives” of images. The relative homogeneity of the composition of the atlas — black-and- white photographs isomorphically distributed over the surfaces of the monochromic screens — therefore serves to produce serial effects which can expose subtle differences and intervals, or to render possible methodical deconstructions of images into their composite parts, but also to create a dialectical play between similarities and differences: the famous anachronisms of the montage (Manet next to Carracci, the contemporary, political imagery of the last few screens, with their suggestive connections between religious iconography and fascism, between the pope and Mussolini) sharply delimit themselves against the surrounding images, at the same time as the returns and transformations that Warburg wanted to trace and diagnose are clearly outlined.

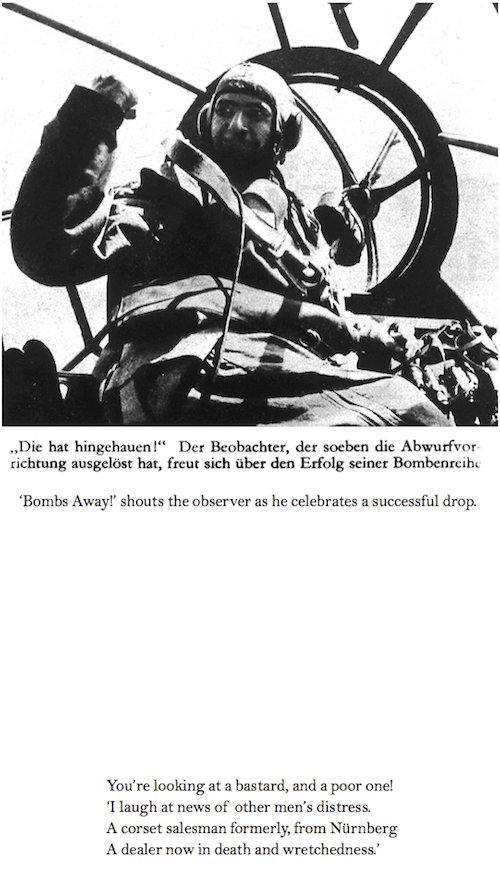

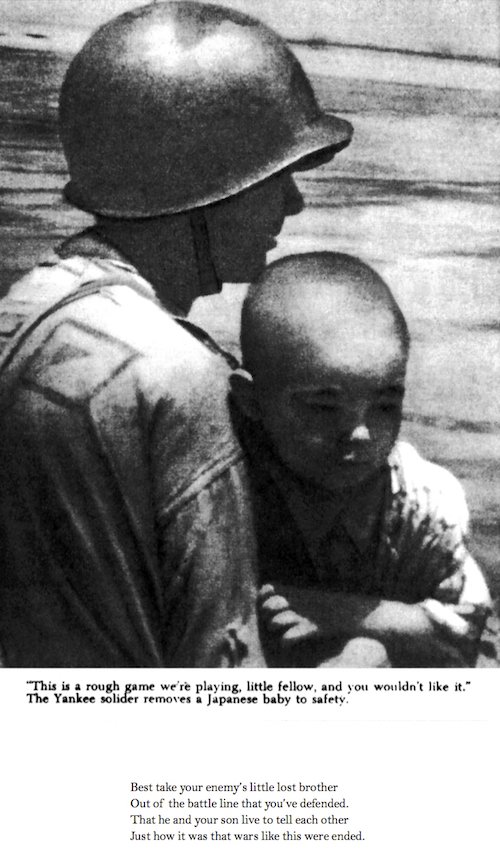

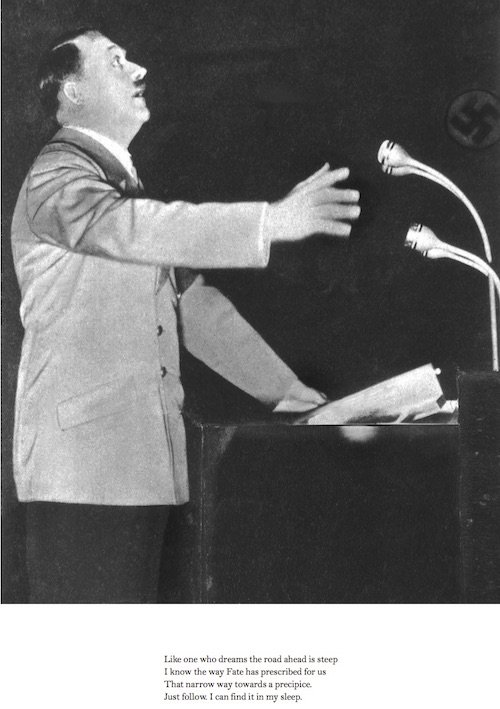

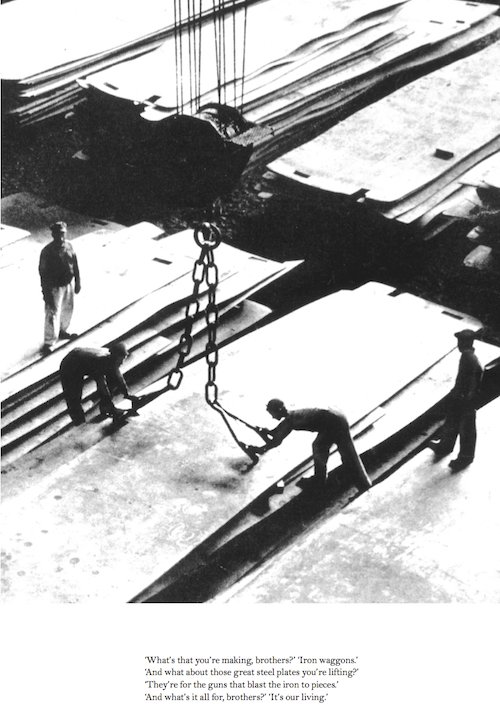

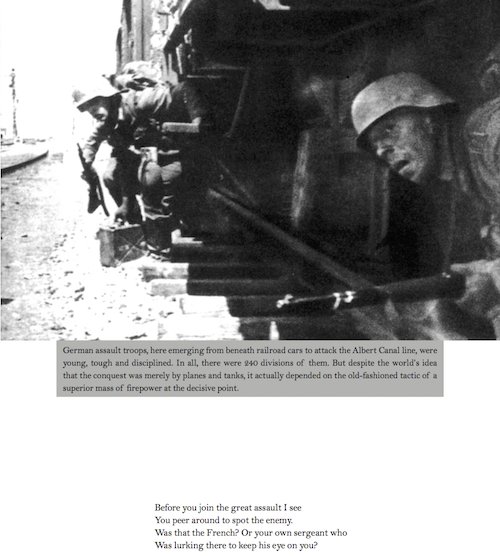

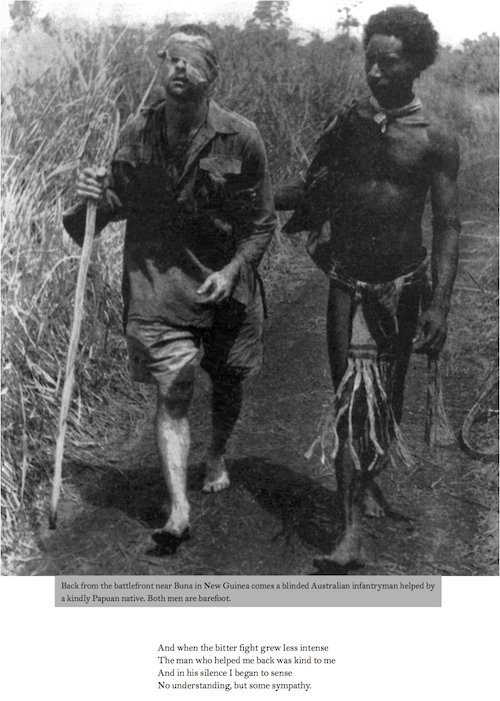

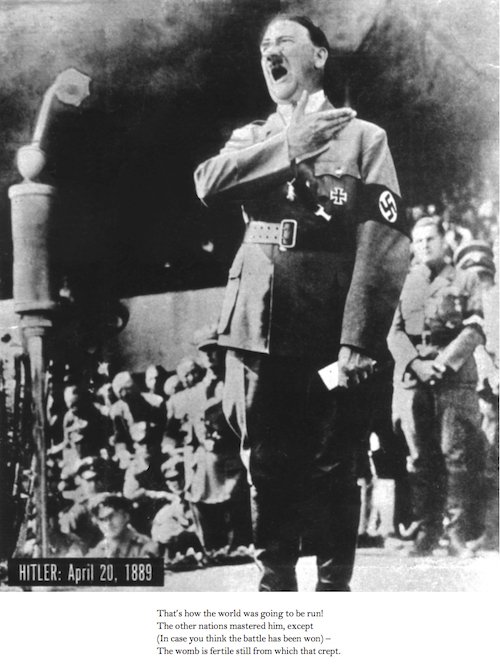

Montage, then, has an analytic force. It dismantles history: it shows the historical object in its heterogeneous temporality and consequently breaks the continuity of a certain established historiography. In Bertolt Brecht, this operation, where the “natural” development of the narrative is distorted and its underlying complexity is rendered visible, has another — very famous — name: distanciation, Verfremdung. In Brecht’s epic theatre, however, the “V-effect” aims not only to disclose the conditions of the narrative and the spectacle, to show the mechanisms behind the stage, but also to render possible a new, critical composition of its elements, now torn away from their apparent naturalness. When Didi-Huberman in Quand les images prennent position approaches Brecht as a montage artist, it is therefore also a question of a third level, a third aspect of his discussion of the montage concept: montage has a synthetic force, an ability to remount the dismantled elements into a critical narrative art or historiography. Quand les images prennent position is a study of two books by Brecht, the Arbeitsjournal and the War Primer, which both apply a montage technique and combine images and texts according to partly divergent procedures. The Arbeitsjournal collects Brecht’s notes from his years in exile 1933–1955, and juxtaposes them with news images and different types of reproductions, according to an open, organic model. War Primer is a peculiar children’s book for grown ups, which in a more systematic fashion combines photographs of the horrors of WWI I with short prose passages and poems. Both of these books, Didi-Huberman says, are based on a distanciation, a demontage which breaks apart the images of the war from their established narratives, in order to remount them according to what he, with Brecht, calls an “art of historicizing”: “an art that breaks the continuity of narrations, extracts their differences and, recomposing these differences themselves, restitutes the essentially ‘critical’ value of all historicity.”24

From Bertolt Brecht’s War Primer, 1955

It would probably not be misleading to claim that Quand les images prennent position is Didi-Huberman’s most ambitious discussion of the montage concept so far. In the different chapters of the study, and by way of a meticulous close reading of Brecht’s two books, he returns to the different ideas and analyses of montage’s capabilities that he had introduced in his texts on Bataille, Benjamin, Warburg, and Godard: montage is the name of the image or the historical object which assembles heterogeneous times and resists assimilation into the continuum of tradition; it is the analytic force, the philosophical or theoretical procedure that dismantles the narratives of history, distanciates the elements of the story, in order to render visible the image or the historical object as montage; and it is the synthetic force, the narratological or historiographic method for remounting the dismantled montage-images into new, critical narratives or compositions, a new montage. In a certain sense one can say that Quand les images prennent position describes the diagram for these different levels in Didi-Huberman’s montage concept: “To distanciate,” he writes in a discussion about Brecht’s term, “is to demonstrate by dismantling the relationships of things shown together and connected according to their differences. There is, then, no distanciation without a work of montage, which is a dialectics of demontage and remontage, of the decomposition and recomposition of all things.”25 A few pages later he repeats more concisely: “This is what montage is: one does not show without dismembering, one does not dispose without first ‘dysposing’.”26 But there is also something else in this text, an explicitly political dimension which is absent from the earlier studies. Didi-Huberman establishes a central distinction between the mode of narrative which takes sides [prend parti] and the one which takes a position [prend position].

The concepts are introduced in a discussion about the conflict between Brecht and Lukács: the programmatic realism which is advocated by the latter “takes sides” by representing a certain, defined reality, mediated through a doctrinal interpretation; the montage which Brecht practices in the Arbeitsjournal and the War Primer “takes a position” by, rather than representing a defined reality, returning to reality its problematic character, rendering it undefined, polyvalent, emptying it of authority. The critical historiography of the montage is therefore also a possible political art of storytelling, a form for resistance and emancipation: just as it may tear away the objects of history from the tradition and render them inaccessible to reductive narratives, it may create a mobility in the order of words, images, and things, tear them away from their positions in a given hierarchy and combine them in a constellation which upholds, even defends their heterogeneity.

There seems to be a turn towards the political in Didi-Huberman’s latest texts, a clarification of a position, a will to articulate a critical attitude and address a contemporary social situation. Quand les images prennent position approaches concrete political issues — of symbolic resistance and emancipation, of the political efficiency of aesthetic forms — which are only suggested, present in the background in the earlier texts on Benjamin, Bataille, and Warburg. And Didi-Huberman’s latest number of publications on Pasolini, the “documentary montage” and the “exposition of the people” are directly inscribed into a search to describe the conditions for the production of “other images” of the “peoples [sic],” images that can resist to and transgress the spectacularization of contemporary politics and the media world’s “over-exposure” of the people.27 The essay Survivance des lucioles, “survival of the fireflies” takes its point of departure in — and lingers on — a suggestive metaphor that recurs in two texts by Pasolini. In the former, a letter written in the poet’s and filmmaker’s youth, at the high point of Italian fascism, Pasolini describes a remarkable experience of political and social community: a night of love and friendship between young men, where they escape from the searchlights of the police, and find refuge on a dark hilltop in Rome, where they witness how “a great quantity of fireflies” form “swarms of fire” around the bushes. The firefly, then, becomes the figure for a minor politics and community, for another people that exists below the forms and orders of “major” politics, a “small light” that glows outside of the beams of the great searchlights.28 In the latter text, “L’articolo delle lucciole,” written in 1975, a few months before his death, Pasolini is, on the contrary, deeply pessimistic: the fireflies are dead, they have been extinguished by a society of the spectacle which drains everything in a blinding light, with an efficiency which even surpasses the tyranny of fascism. Against this pessimism, to which Didi-Huberman finds a correspondence in Debord, but also in Agamben’s latest texts on the power, the glory, and the generalized state of exception, he opposes a thesis — which almost has the character of an axiomatic hope, a principle of faith — about the continued existence of the fireflies in spite of all. The minor people, the other type of community which Pasolini experienced on the hilltop in Rome, “survives” or “lives on” (in “survivance” one should of course hear Warburg’s Nachleben), and can therefore be recorded and displayed in the images of the “documentary montage,” in a form of narrative and historiography which — and here one finds a more clearly political reading of Benjamin — can liberate itself from the “barbarism of tradition” and “expose the nameless.”29

Montage, in short, as a method and model for producing critical images of the people: it can show those who are excluded from the order of major politics, and it can find another, minor political community in the gaps, the fissures in the integrated spectacle of late capitalism. One asks oneself whether these passages of cultural critique in the texts on Pasolini and the exposition of the people — which, while intriguing, are perhaps less original — in a sufficient and exhaustive way account for the politics of montage in Didi-Huberman. The historiography of montage, we may establish, has a politics in his work from the outset. To reveal the heterogeneous temporalities of the historical object, to tear images and words away from their given positions in the great narratives of tradition, to remount them into critical stories — these are all, of course, political activities: it is to resist against a thinking which wants to enclose historical styles, techniques, and objects in “their own” epochs, which wants to establish defined positions and roles for subjects and objects, words and images, which wants to limit the migratory movements of forms and phenomena; it is to shatter the past in order to criticize the present and open other ways of relating to the coming. In other words, montage’s relationship to history — this should be clear, here and now — is complex. Perhaps it is only from such a starting point, given such an argument about the historiographic politics of montage, that one can approach the question of the actuality of montage, of its relevance as an artistic technique, historiographic method or as the name of a general critical project today. Montage, one could say, is precisely the technique, the form, the anachronistic operation which reveals the limita- tions of such a notion of the actual, of today, which exposes the insufficiency of such an idea of a technique or form’s affiliation to its present. In other words, perhaps the tense and direction of this question are misguiding: perhaps one should not ask if it today may be relevant to talk of a general montage principle, but rather how, in what ways montage may function as a principle for untimely resistance against the present.

Kim West is a critic and project researcher at Södertörn University.

Notes

1. Georges Didi-Huberman, Devant le temps (Paris: Minuit, 2000), 39.

2. I here follow John Goodman — translator of Didi- Huberman’s Devant l’image — in simply translating the French “pan” (section, surface, side, etc.) with “pan.” Cf. Didi-Huberman, Confronting Images, trans. Goodman (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005).

3. Devant le temps, 16.

4. Didi-Huberman, Quand les images prennent position: L’oeil de l’histoire 1 (Paris: Minuit, 2009), 109.

5. Idem, Images malgré tout (Paris: Minuit, 2003), 191.

6. Devant le temps, 9.

7. This is an argument that Didi-Huberman returns to in a number of contexts, but which is articulated in the most clear and careful way in Confronting Images, ch. 3: “The History of Art Within the Limits of Its Simple Reason”; Devant le temps, “Ouverture” (and passim); and L’image survivante, part 1: “L’image- fantôme: survivance des formes et impuretés du temps” (Paris: Minuit, 2002).

8. Cf. Confronting Images, 136f, 144ff.

9. Devant le temps, 16, 35, 120, backside.

1 0. Images malgré tout, 152.

11. Sergei Eisenstein, “Word and Image,” in The Film Sense, ed. and trans. Jay Leyda (New York: Harvest Books, 1947), 35f.

12. See ibid, 24–33.

13. Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. H Eiland & K McLaughlin (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), N3, 1.

1 4 . Devant le temps, 10.

15. Ibid, 121.

16. Didi-Huberman, La ressemblance informe, ou le gai savoir visuel selon Georges Bataille (Paris: Macula, 1995), 302.

1 7. L’image survivante, 474.

1 8 . La ressemblance informe, 294.

19. Eisenstein, “Methods of Montage,” in Film Form, ed. and trans. Jay Leyda (New York: Harcourt, 1949), 82. Of course, the opposition between an early, experimental Eisenstein interested in a conflictual “montage of attractions” or “intellectual montage,” and a later, domesticated (Stalinized) Eisenstein, searching for a “harmonic” or “organic” montage, geared to a psychology of identification and empathy, is far too schematic and does not give a sufficient account of his artistic and intellectual development. This question, however, belongs to another text. Cf. Jacques Aumont, Montage Eisenstein (Paris: Images modernes, 2005), 206–257.

20. One can note that this argument seems to be one of the sources for the antagonism between Didi- Huberman and Yve-Alain Bois (and, one is tempted to say, the October historians in general): according to Bois, Didi-Huberman hereby reinscribes dialectics into Bataille’s thinking in a way that is essentially foreign to his philosophical project, and replaces the Hegelian synthesis with a “symptom” which is only another word for the same thing. See Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss, Formless (New York: Zone Books, 1997), 68f, 79f, 266n5. A thorough examination of the different arguments obviously points beyond the limitations of this text, but it seems clear that Bois’ objections are based on a rather summary rejection of Didi-Huberman’s read-ng, which, says Bois, “goes against everything that the present project [the exhibition L’informe, curated by Bois and Krauss at the Centre Pompidou a year before Didi-Huberman’s L’empreinte, in the same exhibition space] is trying to demonstrate” (80).

21. Images malgré tout, 172.

22. See L’image survivante, 464f.

23. They exist only as photographs, and a number of screens are not reproduced in this material. See Aby Warburg, Gesammelte Schriften I I, 1: Der Bilderatlas Mnemosyne (Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 2000).

2 4 . Quand les images prennent position, 68.

25. Ibid, 70.

26. Ibid, 86.

27. See Didi-Huberman, “Expose the Nameless,” in Filipovic & Szymczyk (eds.), When Things Cast No Shadows: Fifth Berlin Biennial of Contemporary Art, exh. cat. (Berlin: J R P/Ringier, 2008), 554.

28. Idem, Survivance des lucioles (Paris: Minuit, 2009), 14ff.

29. Cf. “Expose the Nameless,” 557. See also idem, “Pasolini ou la recherche des peuples perdues,” in Les Cahiers du Musée national d’art moderne, no 108, Summer 2009, 96ff.