Image, Time, Presence

Sven-Olov Wallenstein

i. Image

Georges Didi-Huberman’s two volumes Devant l’image: Question posée aux fins d’une histoire d l’art (1990) and Devant le temps: Anachronisme de l’art et histoire des images (2000),1 together constitute a powerful questioning of our normal understanding of what it means for artworks to have histories, for us to engage with them, and of how they can be said to always overflow and disrupt the interpretative frameworks that we impose on them. Confronting us with a new idea of the “image” and of “time,” Didi-Huberman’s work attempts not only to rethink fundamental methodological aspects of art history, but also opens onto an ontological questioning of the status of images in general that situates itself at the crossroads of phenomenology, psychoanalysis, and a vast array of contemporary investigations into the foundations of subjectivity.

Didi-Huberman’s quest is to descend into the undertow of representation, and to chart those forces that lead to a dismantling of form: in short, to restore the presence of the work as an inexhaustible enigma whose insolubility both calls for and resists infinite interpretation. There is a certain “ruined clarity” that we must learn to excavate, he suggests, and that stands firmly opposed to a demand for identification of forms, which is nothing less than a “tyranny of the visible” (DI 64/52). There is a power of “disruption,” a “tear” or “rend” (déchirure) at work in the fabric of representation, to which art history has most often made itself blind, not just because of some contingent intellectual error, but due to structural reasons that lie as deep as the humanist foundations of the discipline in the writings of Vasari and onwards. To emancipate this force for Didi-Huberman thus also implies a thoroughgoing critique of various traditional modes of art history, most notably the one developed by Panofsky, with its strong (neo)-Kantian emphasis on form and rationality. In such a neo-Kantian discourse, art and historiography mirror each other as fundamentally intellectual processes, leading from a pre-artistic recognition of form, through an “iconic” stage, and finally up to the rationality of “iconology,” and Didi-Huberman proposes a powerful reading of this tradition that brings out its limits. We should always be wary, he suggests, of a history that turns the object into a mirror image of its own “rational” procedures, that takes its “mode of knowing” to be identical with the thing to be known, and that never opens itself to the challenge of the work.

The critique of irrationalism — the “critique of pure unreason” understood as a particularly German phenomenon — indeed became a predominant motif in Panofsky’s work as it evolved in the American context, against which Didi-Huberman proposes a much more fluid and expanded version of critical activity that opens up toward the dimension of unconscious affects and a different genesis of subjectivity. Unlike this tradition, which presupposes an “implicit truth model that strangely superimposes the adaequatio rei et intellectus of classical metaphysics onto a myth — a positivist myth — of the omnitranslatability of images,” and produces a “closure of the visible onto the legible and of all this onto intelligible knowledge” (DI 11/3), whose philosophical summit Didi-Huberman locates in Kant, he wants to restore something of the opacity in the visible, its resistance to translation into iconicity, signification, and codes. (Needless to say, this could also be read as a retrieval of certain underlying motifs in Kant’s own work, and especially so in the case of the third Critique, which should by no means be simply handed over to a limited neo-Kantian reading, as Didi-Huberman often seems prone to do.) In this (seemingly) anti-Kantian task, he also finds a close ally in Freud and the analysis of the “dreamwork,” which shows that the machinations of representation always have their roots deep down in formations below the conscious level, for which even the term “contradictory” may be too dialectical and pacifying since time and logical sequentiality here lose their grip; and also in Lacan, who is rarely cited, but who, by way of a quote from his famous analysis of the gaze as objet a, a “pulsatile, dazzling, and spread-out function” connected to the unexpected and impossible arrival of the Real (the Real object of painting, l’objet réel de la peinture, Didi-Huberman says), in fact seems to get the final word (318/271).

But if the first question posed by Didi- Huberman bears on how we are to account for the existence of such a disruptive moment, and if this necessitates a polemical thrust against a certain model of art history, then we must also be able to proceed to something like an other history that tracks the movements of this very illegibility without performing the same reductive move as its rationalist opponent, and that unearths the various modalities of “counter-images” as they impact on history neither from within nor without, but from a position somewhere at the margin or limit; as we will see, the status of this limit is fundamentally what is at stake here.

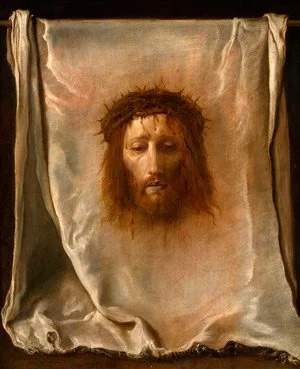

Domenico Fetti, The Veil of Veronica, 1618 or 1622

In this narrative (if this is the right word, which may be doubtful) a particular role is played by the motif of incarnation, as this is understood in certain strands of Christian theology. Drawing on a long tradition of negative “apophatic” theology from Pseudo-Dionysius to Albert Magnus, but also going back to Tertullian’s initial attacks on the Greek view of worldly immanence as the plenitude of visual form, Didi-Huberman locates a necessary break within the mimetic order (of which the Byzantine debates on iconoclasm in the 8th and 9th centuries would constitute a different version), where the impossibility of containing the divine within any finite vessel — linguistic, visual or otherwise — on the one hand entails a negation of representation, and on the other its multiplication, as in the multiplicity of “divine names” in Dionysius, whose very proliferation testifies to their fundamental inadequacy. This break with the iconic for Didi-Huberman implies a re-evaluation of the index, and he points to the Mandylion and the shroud of Turin (as images of Christ that are not man-made, or “not made by hand,” acheiropoieta, as Byzantine theology said) as cases of this indexicality, but also to devotional relics and various forms of the ex-voto in general. These indexes are traces of presence, and instead of pointing ahead towards a mastery of presence within representation, they gesture towards transcendence both in terms of overflowing and withdrawal. And inversely, there is here also a relation to the viewer as an incarnated subject: the medieval spectator does not look for representational devices in the image of Christ, Didi-Huberman stresses, but experiences the body of Christ as in intense relation to his own body, just as the Eucharist becomes a carnal experience of presence and not an abstract and intellectual deciphering of signs.

Didi-Huberman locates a striking instance of this complex presence in the frescos of Fra Angelico, an analysis developed at length in a monograph published the same year as Devant l’image.2 Here Didi-Huberman pursues the theme of a “dissemblance” between infinite and finite that calls upon the work of the “figure,”3 understood not in the sense of Vasari’s idea and disegno, but as a technique of deformation that disrupts the identity of the visible, and in this also makes possible and even necessitates a whole gamut of non-representational painterly expressions that Didi-Huberman traces in great detail. For instance, in the artist’s rendering of the Annunciation, the images take up a dialog with the surrounding white walls of the cell as if to empty out the Albertian istoria, and to announce precisely the transcendence and unknowable quality of the divine. When read in terms of the theology of figure, the “stains” of color that in many paintings seem to yield nothing but inchoate fields become the instruments to pry materiality open to a spiritual beyond without determined form. The four panels of false marble surrounding the fresco, similarly splashed with gushes of paint (evoking violent acts of throwing paint rather than the intellectual composure of the Albertian artist in control of his istoria), which have received little or no attention by scholars focusing on iconographic meaning, for Didi-Huberman come to indicate a hollowing out of the image, a figural gesture of humility before a divine presence whose annunciation could only take place in the very failure of representation.

ii. Time

In spite of all its brilliant exegetical details, textual as well as visual, the overall status of this analysis in Didi-Huberman’s interpretative strategy remains unclear, however, or more precisely put, structurally and necessarily ambivalent. On the one hand he speaks of “those long Middle Ages” (FA 24/10) within which Fra Angelico’s work remained embedded, which seems to accord it a historical location: the painterly version of negative theology would be a vestige of a tradition on the verge of being obliterated by the new optical and technical certainties of the Renaissance, by a visual mastery that becomes the opposite of the Dominican friar and painter’s humility, and subsequently ushers into the analogous certainties of the Vasarian art-historical tradition (which is in fact also how Vasari presents the painter, caught between a devout although artistically inept medieval tradition, and the technically proficient although morally questionable nudes of the present). On the other hand the figural work is read as a critique avant la lettre of a particular visual model that was not yet in place, which gives it a non-historical, paradigmatic quality that cannot be limited to Christian images.4 In this sense the analysis of Fra Angelico is the major piece of evidence for a historical shift, traced through an elaborate exegesis of theology and art at a moment when the subsequent path of Renaissance art was still in the balance, and a model for a perpetual dialectic between representation and disruption in all image-making. This is probably also why the pictorial regime of Alberti, which the Dominican painter’s dissemblant practices of studied visual ignorance allegedly oppose on every point, sometimes appears as almost naturalized — it is “the familiar order of the visible” (15/5), or “the ordinary economy of representation” (130/87).

Fra Angelico, Annunciation, 1437-46

Similarly, the schema of incarnation that first was located with great historical and textual specificity subsequently seems itself to overflow its theological frame and become a condition of possibility for images in general: the power of déchirure, Didi-Huberman writes, should be situated “under the complex and open word incarnation” (DI 220/184, my italics), which seems to grant the concept an indefinite use. In the dense paragraph closing the first section of the book, entitled — with an ironical glance at Kant’s philosophy of religion — “The History of Art Within the Limits of its Simple Practice,” Didi-Huberman seems to amalgamate several interpretations, fusing a theology reconfigured in a Lacanian vocabulary of desire and demand with an imperative of historical specificity (marked by the significant intrusion of a slightly uneasy “at least”), as if to situate a break that at once must be located within history, at the very limit and opening of the visual: in its attempt to “understand the past,” art history, he suggests, “owes it to itself to take into account — at least where Christian art is concerned — this long reversal: before demand there was desire, before the screen there was the opening, before investment there was the place of images. Before the visible work of art, there was the requirement of an ‘opening’ of the visible world, which delivered not only forms but also visual furors, enacted, written, and even sung; not only iconographic keys but also the symptoms and traces of a mystery. But what happened between the moment when Christian art was a desire, in other words a future, and the definitive victory of a knowledge positing that art must be conjugated in the past tense?” (64/52, my italics) The expansive aspect of this move becomes even more clear in the appendix, “The Detail and the Pan [Pan],” where Didi-Huberman draws together many of the preceding arguments and examples in what is probably the great tour de force of the book, a dense discussion of Vermeer’s The Lacemaker (1670).5 Opposing himself to the clarity and exactitude that Paul Claudel once wanted to see in this image, he observes how the figure’s fingers transmute into blots of white color, and how the threads on the table form an confused entanglement. For Didi-Huberman, what the scene provides are obscurities and enigmas, and the “purification” and “stilling of time” that Claudel discerned in fact leads to an extreme “aporia of the detail”(296/250), and rather than cherishing the splendor and triumph of representation as a way to capture the world laid out before our gaze, the painting now speaks of suspension, even its ruin and end. Vermeer’s attention to the details of this world, the worldliness and immanence of his imagery, however, are far removed from the theological discourse of incarnation, and the theory of the screen or “pan” that Didi-Huberman develops obviously refers not only to certain strands of 17th-century Dutch painting, but to a condition shared by images in general.

Johannes Vermeer, The Lacemaker (detail), c. 1669-1671

This tension between the general and the specific is not so much alleviated as it is brought to the fore as a structuring idea in the following volume, Devant le temps, which explores, or perhaps better explodes, the temporal logic of art history. If Devant l’image poses a question to the “ends,” understood both in the sense of aims and endings — both of which are to be taken in the plural — of a certain history of art, the second, a decade later, confronts us with time as the necessary “anachronism” of the work, its capacity to disrupt the order of history.6 Although more loosely structured than the preceding volume (it is organized around three readings, of Pliny, Walter Benjamin, and Carl Einstein), Devant le temps pursues the theme of the disruptive “rend” in order to show that it can neither be understood as some atemporal structure beyond the vicissitudes of history, nor a simple effect or expression of a certain moment in history: the work, Didi-Huberman suggests, or perhaps we should say the work of the work, constitutes an anachronism, a montage of different temporalities that violently undoes the conventional fabric of “tradition.”7

Fra Angelico, Sacred Conversation, 1443

Once more taking its cue from the case of Fra Angelico, Devant le temps poses the question of how we should understand that his work belongs to several chronologies. Restoring a context and historical sources, no matter how profound and detailed they may be, will never allow one to appreciate the fact that the image is not even contemporary with itself — it breaks out of the “euchrony,” a Zeitgeist that is always a result of an idealization, and extends towards a past (Fra Angelico transforming and reworking the theology of figura), but also towards its own future, where a contemporary abstraction that charts the physical act of painting (as in Pollock) may allow us to rediscover the modus operandi of a 15th century painter. There is both a necessity and a fecundity in this type of anachronism, Didi-Huberman suggests, but instead of chastising it as something which prevents art history from finally becoming a science (humanist, as in the case of Panofsky, or in some other version), we should cherish it as something which is profoundly connected to the historicity of thought itself.

iii. Presence

As Norman Bryson has pointed out, the attacks on Panofsky mounted by Didi-Huberman may seem a bit overdone, above all since the model derived from Panofsky has long since ceased to function as a paradigm for art history, which during the last decades has come to face an almost overwhelming pluralism.8 In retrospect we may however situate Didi-Huberman’s two books, both in what they reject and what they propose as an alternative — what they “confront” us with or place “before” us (devant): images and time — within a larger theoretical shift, which may serve as an interpretative grid for at least some of the current transformations, and which has received many names: the turn towards “presence” or “affects,” towards and “anthropo- logical” understanding of images, or, ironical as this may sound if we bear Didi-Huberman’s sustained attack on the humanist tradition in mind, the “pictorial” or “iconic.”9

Regardless of what terminology we choose, this shift may be said to take place in opposition to a “linguistic turn” that seemed to place everything under the aegis of language, and whose high point was the advent of structuralism and its various aftermaths in the mid to late ‘60s. Today it seems as if images and visual objects have once again acquired an agency of their own, a capacity to act on us in unforeseen ways. This is undoubtedly on a more straightforward level due to their sheer ubiquity: once theorized under the rubric of “simulacra,” a concept that still betrayed an unmistakable if not acknowledged nostalgia for a Real beyond representation, the image in its unfettered state has become an autonomous power that neither reveals nor conceals, but is itself fully real. This also cuts through the status of images as mere representations, and in this also renders questionable the classical concept of “ideology,” which ever since Marx’s somewhat simplistic use of the camera obscura model in most cases has been predicated upon a rather reductive view of consciousness as (deformed, distorted) representation. Today, it is claimed, images are presentations, and even if any trust in a clear-cut distinction between presentation and re-presentation, for instance in the form of a massive split between some immediate access to reality and its linguistic mediation, seems more than naïve on the philosophical level — and this is unfortunately how the discussion is often phrased — the claim that we must retrieve the efficacy of the visual, its visceral and physical effects and affects, as a problem within theory itself, is highly significant. The emphasis on “reading” the world may to some extent have blinded us to its “being,” as Hans-Ulrich Gumbrecht says (although this is indeed too a distinction that must be subjected to severe scrutiny). There is, he claims, an intentionality within the objects themselves, a way in which they produce “presence effects” that must be accounted for.10

Such “presence effects” are also closely related to a discourse on “affects,” which today has become a pervasive theme in much cultural theory, from media and literary studies to architecture and philosophy.11 This undoubtedly translates a widespread fatigue with inherited models of critical theory that are based on fixed models of experience and subjectivity, and they call for a more malleable and flexible way of understanding the way our sensorium is constructed. But even though these debates obviously become highly complex as soon as one enters into the details, on a more general level they tend to split up along well-known and predictable axes. On the one hand, there are those who understand the concept of affect as pointing towards the necessity of an affirmation that would reject “theory” as an obstacle to experimentation and production, on the other hand those who perceive affectivity as a renewed possibility of resistance that would be based in the hidden potential of the body itself, beyond or beneath the conscious level.

The claim for a “presence” of the visual, that there is a “life” lodged within images to which we must respond, indeed flies in the face of a certain type of interpretation, predominant within what has become “cultural studies,” which seals the visual object within an analysis of ideological formations whose representation it would be, and that consequently calls for a mode of deciphering that eventually uncovers the true meaning — a truth that becomes all the more compelling by breaking away from the surface order of phenomena. A critique of images that reduces them to mere ideological reflections seems to deprive them of life, in transferring all of the movement and intelligence to the one who “reads” them; against this, the theory of presence requires that we restore something of the encounter, the way images confront our bodies with their physical texture in a kind of violence of the surface.

But although it may be true that the skin is the deepest thing of all — “Ce qu’il y a de plus profond dans l’homme, c’est la peau,” as Valéry famously said12 — this does not imply that we must simply discard depth in favor of a naïve immediacy, instead it may just as much make us aware of the intricacies of the surface/depth model, as any more thorough consideration of the surfaces, folds, and crevices of poetry surely will tell us.

To some extent, it seems as if the emphasis on presence and affect would attempt to relocate the “object” (and/or “subject”) of critical theory — presuming that this term should be preserved, as I do — to a new region, where the entanglement of the subjective and the objective is more acute, and where all appropriating hermeneutics comes to and end. But we must also note that this may be a struggle against a non-existing enemy, provided that we make the case of the opponent as strong as possible. Indeed, few thinkers have emphasized the power of the musical work to undo our conceptual schemes to such an extent as Adorno, and few have highlighted the capacity of the visual art object to question all inherited views of perception more than Merleau-Ponty — all of which indicates that the difference between interpretations that seal the work in pre-given categories (of art history, literary history, cultural studies, critique of ideology), which undoubtedly do not only exist but in fact provide the bulk of academic discourse, and those that put these categories themselves at risk, runs within these traditions themselves, and can not be used to pit them against each other.

If it is possible to locate Didi-Huberman within this theoretical shift, as for instance Keith Moxley does,13 then we must also note the extent to which he resists it, i.e. the extent to which the claims for presence imply a certain anti- or non-theoretical stance that opts for immediacy, enjoyment, and a farewell to reflexive discourse (which obviously, no matter how sophisticated some of its proponents may be, squares all too nicely with demands of our present culture industry). His critique of the art historical tradition may undoubtedly be mapped onto the critical reactions against a certain view of images as simply bearers of an ideology that could be decoded in another discourse whose authority remained unquestioned (be it social history or psychoanalysis, the point here not being the content but the position of the theory “supposed- to-know,” to paraphrase Lacan), where the cultural analyst effortlessly assumes the places of the iconologist. But his re-evaluation of the power of images, particularly in their “anachronic” dimension, also indicates the temporal complexity that must be accounted for in any theory of presence. It effectively undercuts the simplistic division between representation and presentation, and shows the considerable resources that still exist in the traditions of critical theory, psychoanalysis, and phenomenology. In short, if his work rejects certain models of art history and theory, it does this with the intent of reinvigorating theory, and to render it more open to the challenge of the object; and if it rejects certain rationalist models of history, it does so with the intent of opening us up to a dimension of historicity that may be all to easily lost in the certainties of various forms of social-historical analysis. Seen in this context, the considerable polemic energy that runs through the work of Didi- Huberman is not what makes it so resourceful for the contemporary reflection on images. It is true that by reading books like Devant l’image and Devant le temps we learn a lot about what may be wrong with neo-Kantian aesthetics, Panofsky’s iconology, Vasari’s rational disegno, etc., and with a certain type of (perhaps somewhat malevolently portrayed) art-historical discourse that wants to be done with the object — but their fundamental thrust lies in their capacity to invent a powerful counter-discourse that mobilizes an other side of the philosophical tradition in order to restitute an agency to the work that calls for a renewed effort of thought.

Notes

1. Devant l’image. Question posée aux fins d’une histoire de l’art (Paris: Minuit, 1990); trans. John Goodman, Confronting Images: Questioning the Ends of a Certain History of Art (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2009). Devant le temps: Histoire de l’art et anachronisme des images (Paris: Minuit, 2000). Henceforth cited as DI (French/English) and DT.

2. Fra Angelico: Dissemblance et figuration (Paris: Flammarion, 1990); trans. Jane Marie Todd, Fra Angelico: Dissemblance and Figuration (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995). Henceforth cited as FA (French/ English). For more on this book, see Daniel Pederson’s essay in this issue.

3. In many respects the theory of “figure,” which eventually comes to oppose the “figurative” and the “figural,” and which Didi-Huberman develops on the basis of a reading of medieval philosophy is close to Lyotard’s idea of the “figural,” which similarly draws on a cross-reading of phenomenology and psychoanalysis, most systematically developed in Discours, figure (1971). Lyotard’s pioneering work however receives no attention in Didi-Huberman’s account of the image, except for a cursory reference to his discussions of Barnett Newman (DT 247, note). For a discussion of the importance of the figural in Lyotard’s early work, see my “Re-reading The Postmodern Condition,” Site 28 (2009).

4. For a discussion of this tension, see Alexander Nagel’s review of Fra Angelico in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 78, No. 3 (September 1996): 559–565.

5. In focusing on Vermeer Didi-Huberman obviously has a great predecessor in Proust, when the latter in La prisonnière describes the last moment of Bergotte, absorbed at the very instant of his death by the precious materiality of the small patch of yellow color (la précieuse matière du tout petit pan du mur jaune) in Vermeer’s View of Delft; see the commentary to this passage in DI, 291ff/245ff and 314/67.

6. The questioning of the authority of historiographic reason is by no means limited to Didi-Huberman. The year after Devant l’image, a similar note was struck by Daniel Payot, in his Anachronies de l’oeuvre d’art (Paris: Galilée, 1991), and the same year Jean-François Lyotard could claim, from the somewhat different though not entirely unrelated vantage point of a theory of the sublime, that “there is no history of art, only of cultural objects”; see Lyotard, “Critical Reflections,” trans. W. G. J. Niesluchowski, Artforum (April 1991), 29(8): 92–93.

7. As Didi-Huberman notes (DT 25, note 31), the book should be read in relation to Deleuze’s Cinéma 2: L’image-temps. Separated as they may be in be their “philosophical sensibilities,” these two works nevertheless both partake in a powerful attempt to rethink the relation between art and history, which first needs to pass through a negation of a historicism that seals the work in time and deprives if of its agency, which however is only a first step towards recovering a connection to history, or a “faith” in the world, as Deleuze says; cf. L’image-temps (Paris: Minuit, 1985), 322ff.

8. See the review of the English translation of Devant l’image, in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 75, No. 2 (June 1993): 336–37.

9. For an overview of these discussions, see Keith Moxey, “Visual Studies and Iconic Turn,” Journal of Visual Culture 7(2), 2008: 131–146. The “pictorial turn” was proposed by W. J. T. Mitchell a decade and a half ago, in his Picture Theory: Essays on Visual and Verbal Representation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), and restated more emphatically in his What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2205). On the possibility of a general “anthropology of the image,” see Hans Belting, Bild-Anthropologie. Entwürfe für eine Bildwissenschaft (Munich: Fink, 2001).

10. Hans-Ulrich Gumbrecht, Production of Presence: What Meaning Cannot Convey (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004). It must be noted that Gumbrecht’s idea of presence both draws heavily on Heidegger and argues for the continued relevance of Derrida (in close connection to the idea of “birth to presence” through touching in Jean-Luc Nancy, to which Derrida’s own book On Touching constitutes a thoughtful response), which should make the distinction between “being” and “reading” difficult to uphold. In fact, already in Merleau-Ponty any sharp divide between “being” and “reading” seems impossible, if the latter is understood as a diacritical movement of spacing and temporalization that engages our being-in-the-world to the fullest extent.

11. The theory of affects has been put forth most eloquently in the writings of Scott Lash, who extends its genealogy back to Tarde, Bergson, and Simmel, and inscribes it in a general movement towards a new “vitalism” (a concept whose associations to irrationalism significantly made it into something of a bad name within earlier critical theory); see, for instance Lash and Celia Lury, Global Culture Industry (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007). In a somewhat different fashion Maurizio Lazzarato, who also draws on Tarde, develops a theory of “noology” or “noopower,” a power that extends Foucault’s biopower into the substructure of perception; see, for instance, Les Révolutions du capitalisme (Paris: Empêcheurs de penser en rond, 2004), or Videofilosofia. La percezione del tempo nel postfordismo (Rome: Manifestolibri, 1996). For an application of the idea of presence to architecture, where it seems to have gained a particular currency, see the contributions in Archplus 178 (2006), “Die Produktion von Präsenz.” For a discussion of affectivity as a critical resource, see Jeffrey Kipnis, “Is Resistance Futile?” in Log 5 (Spring/Summer 2005). These discussions in fact to some extent appear to return us to certain aporias within earlier versions of (the death of ) critical theory, for instance in the fascination with intensity in Lyotard’s work from the early ‘70s (and in fact, Lash and Lury place their investigations into the contemporary culture industry under the rubric “libidinal economy”), which he first opposed to the critical theory of Adorno and then, in a consciously self-defeating move, to theory in general. The return of these figures of thought is indeed significant, and I discuss the implications of this for critical theory (it must be stressed that this challenge cannot be simply dismissed, if we are to grasp the present) in more detail in The Silences of Mies (Stockholm: Axl Books, 2008), 68–80.

1 2 . L’Idée fixe (1931), Œuvres I I (Paris: Gallimard, coll. La Pléiade, 1960), 215. For Didi-Huiberman’s analysis of skin and depth, see La peinture incarnée (Paris: Minuit, 1985), 20–28.

13. “Visual Studies and the Iconic Turn,” 134f.