Form in Art and in Value

Josefine Wikström

Lecture given at Royal College of Art, December 9, 2021

I have titled my talk here today ‘Form in art and in value’. With ‘art’, I mean the concept as it developed philosophically – primarily in German idealism – as well as practically and institutionally in western Europe from the late eighteenth century, in a capitalistic and racist modernity alongside institutions like the nation state, scientific racism, and the bourgeois public sphere.[1] The concept of art I deal with here is thus bourgeois and modern in the sense that it is as inseparable from capital as it is from the different oppressing institutions through which capital has evolved, such as sexism and racism. By ‘value’, I mean the specific social relation of production which appears with the form of production termed ‘capitalism’, a term used for the first time in the mid nineteenth century.

My interest lies in how these two concepts can be thought of in relation to one another in the context of Western capitalist society after 1989, a period that by some is termed ‘neoliberal’, ‘post-industrial’, or ‘post-Fordist.’ My focus is on how what we might call the form or the autonomy of art functions in this period, a period that I simply call ‘contemporary capitalism.’ This is a question that has gained new relevance in the past two decades. Whereas some argue that art’s autonomy is threatened by identity-politics both from the right and left others make the claim that the main issue is the increased commodification of art and academia by financial capitalism.[2] Whilst the first perspective is romantic, the second one leaves us with undialectical sociological descriptions of the current state. Both nevertheless map the context of the question of art’s autonomy in contemporary capitalist society.

The main point I want to make is that although we need to get a grasp on the current state of art and of value – something I will touch upon in a minute – we need to, I think, approach the problem from the question of ‘form’ and ‘social form’ rather than mere sociological and phenomenological descriptions of what the current state appears or feels like. Consequently, the broader questions I am asking are: What is the relation between the social forms of life under capital, especially the social forms of capital since the 1990s, and the forms of art in the same period? How might the concepts of ‘form’ in art and the ‘social form’ of value help to understand the present moment? These are very broad questions that I will only touch upon. But they are a starting point.

First, however, I want to begin by sketching a kind of background image of two tendencies in contemporary capitalism and in art from the 1990s onwards from the point of view of historians, economists and art theorists who have worked with these questions over the past two decades or so. I will then try to show why it is not enough to tackle the problem from such an angle, and from there move into the philosophical concept of ‘form’ and especially ‘social form’ in art and value, particularly in the work of Karl Marx and Theodor W. Adorno. For Marx, the capitalist mode of production is essentially a form, in the sense of a relation. This is something that Adorno develops when he carves out his notion of art as autonomous . Last, I will try to make some preliminary conclusions about the specificities of the capitalist economy since the 1990s roughly and the forms of art in that same period.

First tendency:

The on-going crisis of capital and the shift in the 1970s

Let me begin with the background image against which I am interested in speaking about form, or within which I think it is necessary to think about form. Over the past twenty years or so, political economists, historians and sociologists have wanted to show that the capitalist system and the production of capital is in its last phase. Already by the end of the 1990s, American historian Robert Brenner was arguing that capitalism, since at least the 1973 oil crisis, had been on what he calls “the long downturn.”[3] In that time, in primarily the US, EU, and Japan, economic performance (measured in parameters like GDP), decreased massively, as did the rate of growth investment (the primary sources of the decline in the productivity and the major determinant of increase in unemployment). Similarly, the French economist Thomas Piketty has shown how, in the same period, wages have gone down for everyone, inequality has risen, and value-production moved from labour to property.[4] Along the same lines, German sociologist Wolfgang Streeck argues that although crisis is an inherent logic of capitalism, the current capitalist crisis (on-going since the financial crisis of 2008) is different from previous ones. He writes: “Capitalism […] was always a fragile and improbable order and for its survival depended on ongoing repair work. Today, however, too many frailties have become simultaneously acute while too many remedies have been exhausted or destroyed.”[5] Some of the tendencies on which Streeck bases his argument that capitalism’s crisis at the moment is ontologically different from crises such as those of the 1930s or 1970s, are declining growth, intensifying distributional conflict, rising inequality, vanishing macro-economic manageability, growing indebtness, explosion of public and private debt, suspension of the progression of post-war democracy, rise of oligarchic rule, failure of states to limit the commodification of nature and money. All these tendencies, according to Streeck, will lead the capitalist system to erode from within.

A final example comes from the viewpoint of a strand of German value-criticism [Wertkritik] that is also sometimes understood as one of the many crisis-theories. That is, theorists who follow Marx’s value-form theory (the formula in Marx that shows how value is produced in capitalist relations) but who takes it further. Like Streeck, they argue that the ongoing crises that are internal to capitalism as a system since the oil crisis of 1973 have reached a new level. Previously, capital had expanded, which also meant that distribution of wealth expanded (with its so-called golden years between 1949 and 1970 when state governed Keynesian capitalism was at its height); in contrast, over the past thirty years, the development of computers and microelectronics has created a system where “the commodity production […] pushes away more labour than it can absorb.”[6] More examples of thinkers who argue that the capitalist system in the West is currently disintegrating from within can be mentioned. Not least Marxist-feminist theoreticians of reproduction, who argues that the Keynesian welfare state governed capitalism is in crisis, and that this is a crisis primarily of reproduction of health, birth and education.[7]

Art since the 1990s and onwards

Now, what has happened to art in the same period? It is worth noting that from the viewpoint of art theorists, sociologists and historians, the period from the 1970s and onwards differs significantly from the post-war period of the 1950s and 1960s. Two points can be made here: The first at the level of the form of art – the concept to which I will get to – and which is to do with what Peter Osborne has termed the tendency in contemporary art towards “increasingly ‘individual’– highly individuated – works”[8] (what Adorno understood as contemporary art’s constant drive towards nominalism). The second point concerns the institutional changes in art since the 1970s onwards, and specifically since the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Image from the exhibition When Attitude Becomes Form, 1969, curated by Harald Szeemann at Kunsthalle Bern

So firstly, the story is familiar: at the height of the capitalist golden years in the 1970s medium-specificity broke down, post-media genres like performance exploded and the dematerialisation of the artwork was a fact. The forms of art became relational, performative, practice-, action-, and task-based. Perhaps best described in the title of Harald Szeemann’s exhibition When Attitudes Become Form presented in 1969 in Bern. Looking further, it is clear that the forms of art that emerged in the early 1990s are extensions and development of this individualisation, dematerialisation and socialisation of the artwork: socially engaged practices, activist art as well as the invention of the dance choreography-exhibition. Danish art historian Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen argues that art after 1989 primarily takes the form of relational aesthetics, art activism and socially engaged art. Similarly, and even more to the point, North American art theorist Leigh Claire Le Bergh argues that so-called socially engaged art reflects the crisis of capitalism since the 1970s onwards, and in particularly by being a kind of de-commodified labour.[9] Marina Vishmidt and Kerstin Stakemeier also argue effectively for a new kind of autonomy in art by juxtaposing the racist and sexist aspects of the reproduction of capital since the 1970s onwards.[10]

Book cover from Lucy Lippard, Six Years

At the institutional level, Bolt Rasmussen argues that the “relative autonomy” of art and of academia, which has existed for two hundred years or so, are under pressure from within. Art via the culture industry and academia via the commodification of education and research. Although Adorno and Horkheimer wrote about the culture industry as early as 1944, they could probably never have imagined the contemporary global art market’s tendencies of mega biennales, the “increased mercantilization of the art institution”,[11] and the fact that “art today is closely tied to the transnational circulation of capital.”[12] Or as art theorist Sven Lütticken puts it when he argues for the term ‘aesthetic practice’ instead of ‘art’, and asserts that the former term is more accurate since over recent decades we have seen an “increasing integration of art into the so-called ‘creative industries’ and its transformation into a financial asset with a cultural cachet.”[13]

If this general picture of art and of capital in the West over the past thirty years is true, what can we do with it? How are we to understand it except as pure sociological descriptions of the current situation or a simple economic determinism between the two? What are the social forms of value-production that govern the modes of production of art? What to do philosophically and intellectually with this information?

In the current literature of this crisis ridden state of art and capitalism, I think there is a tendency to merely describe this situation with digits, numbers, and feelings, which sometimes simplifies the situation. This tendency either tags along with the Italian Marxist assumption that all social relations already are subsumed under the capitalist mode of production, including feelings, services and thus also art;[14] or one argues along the line of a Foucauldian narrative that in neoliberalism everyone relates to one another as assets and human capital.[15] It is here that I think it is useful to speak about the concept of form, which is closely related to the notion of autonomy in both art and value-production. Similar to how the term autonomy in moral philosophy and in art stand for self-government and self-movement, form can, I think, capture how art might be able to do something with the social forms of life. Without being able to come to any conclusion, I would like to develop the concept of form in art and in philosophy to understand the changing role of art’s autonomy a bit more philosophically, and hopefully in a bit more detail.

Form: Hegel, Marx, Adorno

The word ‘form’ comes from the Latin forma, probably borrowed from the Greek term morphe.[16] In philosophy, the concept of form can be traced back at least to Aristotle’s Metaphysics where he contrasts the Greek words hyle meaning “wood, matter” with morphe referring to “shape or form”. Aristotle creates an opposition between these concepts, designating potentiality to matter – hyle, meaning that it is shapeless and homogenous, and of form – morphe – he asserts that it is actual, substantial, and meaning giving.[17] It is not hard to see how the often-referred-to dichotomy of form and content partly derives from Aristotle’s separation of the two. Further on in the history of Western philosophy, the term also becomes significant, in, for example, Kant’s thinking and in his Third Critique – The Critique of the Power of Judgement (1790) – which is the part of his critical philosophy concerned with his aesthetics and thoughts on the beautiful.[18] It is not however, until Hegel’s “dialectical philosophy of form”[19] in his Science of Logic (1812-1815) that the Aristotelian bifurcation of form and content is questioned radically. In contrast with the classically Greek philosophical idea of matter/content as homogenous and form as meaning-giving, matter/content for Hegel is formgiving and that which gives form.[20] It is then in Marx’s work where we, after Hegel, find an even more radical critique of the dichotomy between form and content. It is this critique to which I will now turn, before moving onto the way in which Adorno takes such an understanding of form into his understanding of the artwork in modernity.

Social form in Marx

Illustration of a table-turning séance from Félix Roubaud’s 1853 text, Les Danse des Tables

It might seem out of place to talk about potential aesthetic categories like form and content in Marx’s work, especially in the economic, so-called mature, writings. But for anyone who has read Marx it does not come as a surprise that aesthetic form is important for him. His use of gothic language and theatrical metaphors and figures often gives a “parodic and self-deconstructive” character to the text.[21] Just think of the dancing table in the first chapter of Capital, out of which supersensuous phenomena like value grow. We might also think of Marx’s method as a way of understanding form in the way that he progresses from the abstract categories of value and labour, down to the more concrete ones, such as population and class.[22] In stark contrast to the already set norms of methods and form in standard conceptions of the discipline of economy today, Marx’s form – or method – of analysing capital was also part of his analysis – critique – of capital. Form and content are inseparable in his method.

Apart from these aspects of form, the concept of form also appears in Marx’s work at an even more fundamental level. One where form is understood as a historically specific materialist relation. This was already present in Marx’s early works, such as The German Ideology (1846) – jointly co-written with Friedreich Engels and only published posthumously in 1932 – where it is asserted that that the capitalist form of production has a specific social form, and that there is no general or natural mode of production, but rather that each mode of producing is a specific social form.[23] This means, as Patrick Murray writes, that the capitalist mode of production is not a production of “wealth in general” but “wealth in a specific social form, the commodity”,[24] which creates a specific form of life.

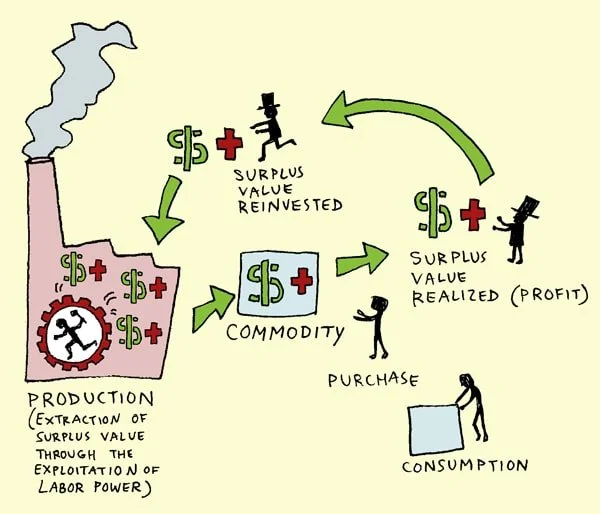

The best examples that demonstrate how social form is key for the way Marx thinks, are the concepts of commodity- and value-form introduced in his magnum opus, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (1867). The value-form is the term used by Marx to describe the specificity of capitalist societies: the capitalist commodity, which is dialectically constituted of use-value on the one hand (something that one can use), and exchange-value on the other. The exchange-value of a commodity does not have any physical features but is a pure social relation, which appears when two use-values are in exchange and an abstract equivalent relation is created between the different usages as well as the individual labours put into these things. Exchange-value, or simply value, is the specific social objectivity – its social form – operating in capitalist societies. The social form of value is the relation through which commodities, and in extension people, relate to one another in a capitalist system, and in which one is abstracted against one another. The content of the social in capitalist society, we might say, is the form of it. Social form for Marx in capitalism is thus historically specific and the opposite of Aristotle’s form-content opposition.

Form in Adorno

Form is also central to the work of Frankfurt School thinker Theodor Adorno, whose conception of art is still the most advanced and thus relevant – if in need of an update – attempt to understand art’s entanglement with value in contemporary times. Firstly, form is central to his overall philosophy and way of presenting his philosophical ideas. The style of his essayistic writings is dense, paratactical and non-systematic.[25] The philosophical consequence of this non-separation of the presentation [Darstellung] of philosophical ideas from the ideas themselves is that his philosophy can be understood as critical of all systematic philosophy from Descartes to Hegel.[26] This is also why Adorno’s writings, according to Gillian Rose, can be thought of as “exemplars of negative dialectics”, that is, as “anti-texts.”[27]

Whilst form is crucial for Adorno’s conception of philosophy and for his presentation of his ideas in writing, it also holds a central position in his conception of art, which he sometimes terms “nominalist” and at other times “autonomous.” I first need to say something about how he understands art in order to be able to then speak about why form plays such a crucial role in it. Art, for Adorno, is a historical category that emerges with the broad process of modernity, in which art is separated from myth, becomes secularized and in this process also becomes autonomous. Art is, in this sense, for Adorno, always double, a so-called “social fact.”[28] The artwork for Adorno, and as Frederic Jameson noted already in the 1970s, is therefore always juxtaposed “with some vaster form of social reality which is seen in one way or another as its source of sociological ground”.[29] Such a concept of art runs through all of Adorno’s writings on literature, art and music, but is specifically present in the first section of the posthumously published Aesthetic Theory entitled “Art, society and aesthetics.” Here he states that art is from empirical reality yet separates itself from it. This means that art is a product of and is constituted by the division of labour in society – it is a commodity, and is made up of social techniques through which the production of commodities also is being produced. Artistic method, he writes:

corresponds to societal development. […] Or to put it more cautiously, the dialectic of art resembles the social dialectic without consciously imitating it. The productive force of useful labour and that of art are the same.[30]

But if the content of art for Adorno is the empirical reality of the society in which it exists, how does it become or differentiate itself as art? It is that here the concept of form becomes central. In the same first section of Aesthetic Theory, he writes that “art becomes a qualitatively different entity by virtue of its opposition, at the level of artistic form.”[31] Differently formulated: “art’s opposition to the real world is in the realm of form.”[32] Further, and in relation to what Adorno terms a materialist and dialectical aesthetic, he writes that art’s “‘law of motion’ and its law of form are one and the same.”[33] To put it bluntly, the artwork for Adorno has to be produced by the most developed techniques and forms of labour for it to have relevance. This is the empirical content of art that makes it part of society. But the artwork needs an inner logic, a form, that makes the social content separate from the empirical reality out of which it is made. But what, more specifically, does form mean for Adorno with regards to the artwork? What is artistic form for Adorno? And how might it relate to Marx’s understanding of social form as supersensuous value?

Firstly, Adorno’s concept of artistic form has little to do with an empirical understanding of colours and shapes that affect the subject of the art, for example. Neither has form in Adorno anything to do with the North American post-war art critic Clement Greenberg’s formalism of the medium. In contrast to both ways of perceiving form, Adorno follows Marx’s understanding of social form, which implies, just like the value-form in Marx and as we have seen, a specific historical social relation between people, artistic form is also a specifically historical social relation. But the social form of the artwork is both identical and non-identical with the social form of capitalism – the equivalence. For Adorno, art’s relation to its social reality – capitalism – is one of negation and this negation is mediated via the form of the artwork. He writes: “Art is related to its other like a magnet to a field from iron filings.”[34] Art becomes, for Adorno, autonomous by way of negating the society from which it is produced. This means that the way society reproduces itself in a specific historical moment, for example through a specific division of labour and through certain techniques is also the way art reproduces itself. At the same time, by being art, through its form, art negates this same society. This is the autonomy of art for Adorno. Form is what makes art autonomous. “Form is thus the result or mark of the process by which the work of art is made, but never appears as merely subjective or arbitrary.”[35] Adorno’s concept of form is thus opposed to an Aristotelian idea where form is meaning giving and content is shaped by form. Rather Adorno follow’s Hegel’s critique of the separation of form and content, and form is instead what Adorno calls “sedimented content”. [36] That is, for example, specifically historical materials and techniques arranged into an inner logic, that appears as a form. This inner logic is the presentation of the subjective aspect of the artwork (that is the artist’s hand for example), but which has forgotten about itself and instead presents itself as a form.

Secondly, artistic form for Adorno is twofold and appears at different levels.[37] We can think of the form of art as: a) the form of individual artworks, that is the techniques, and modes of production and materials through which the artwork is made for example, the context of its production, as well as the artist’s mastery over materials through techniques; and, b) the form of genres in art and the way they refer to different kinds of societies and thus the development of formal traditions. Finally, and perhaps most important for us here, for an artwork to stay art it needs to develop its form in each instance, in the sense form is understood above. In a section in Aesthetic Theory entitled “Universal and particular”, Adorno writes: “Nominalistic works of art again and again require the guiding hand, the intervention of which they must disguise in principle.”[38] That is, they must break with previous forms (previous techniques and materials) of art to keep on being art. This is the law of movement of form in art for Adorno, exemplified for example by Arnold Schonberg’s rejection of harmony and his introduction of the twelve-tone technique into compositional technique. Or Samuel Beckett’s literature, which for Adorno, in its use of montage and documentation, is the most realistic modern literature because it reflects the abstract equivalent relations between people in developed capitalist societies. The form of the artwork for Adorno, thus both reflects the social abstract form of value of capitalism, yet also breaks with it, through the specific arrangement of materials in the artwork. The question is, what are the new forms in art of today that might be said both to reflect the disintegrating crisis of capital and distinguish itself from it?

Preliminary Conclusions:

Social form of capital in art and in capital from 1989 onwards

The value-form in Marx, whereby wealth is represented through the exchange of commodities, is still present and at work in capitalist Western societies. Workers get up before the sun rises in Gothenburg to assemble cars in a Fordist organised manner; whilst at the same time, most commodities are produced by less well-paid workers in the global south, and often in undemocratic states like China. In parallel, northern European service and tech-companies like Spotify are valued more and more each year, yet without producing wealth in the sense of labour and the distribution of wealth via income taxes to the state. From this reformist Keynesian welfare state perspective, the value-form, we might say with Wolfgang Streek to whom I referred to earlier, beings to crumble from within. At the same time, with the introduction of New Public Management and the organisation of governmental authorities like companies, there is an intensification of a mimesis of the value-form within public services such as higher education, health, and schools, and thus a creation of quasi-markets. The paradox here is that wealth, in the sense of the production of capital as Marx put it, does not actually take place – and as the many economists and writers I mentioned at the beginning have noted, wealth and productivity have decreased since the 1970s – yet it “feels” as if life is more and more subsumed by the social form of value. There is thus a tendency to behave as if all activities and all social relations are relations of value. Yet this is not really true, but is perhaps instead a part of the neoliberal ideology, which, in the words of one of its founders F. von Hayek, wants us to behave laissez-faire and without any reason, rationality or planning.[39] The current state is not neoliberal in the sense that everything is commodified or all of life is subsumed under capital – current society is neoliberal in the sense that it creates a strong fiction in which the only belief is that of capitalism.

In 1968, the year before he died, Adorno gave a lecture called “Late Capitalism or Industrial Capitalism? The fundamental question of the present structure of society”, in which he asked “whether the capitalist system still predominates according to its model, however modified, or whether the development of industry has rendered the concept of capitalism obsolete”.[40] In it he argues against many then contemporary sociologists who (similar to sociologists of our times such as Streeck) claimed that capitalism was now in a late phase and that “the world is so completely determined by the unprecedented growth in technology that the social relations that once characterized capitalism – namely the transformation of living labour into a commodity, with the consequent conflict between the classes – have now lost their relevance or can even be consigned to the realm of superstition.”[41] Adorno argues against such a mistaken “subjective economist”[42] view. Although after the Second World War the working-class in the West became integrated into the middleclass and lost their worker identity, the capitalist system, Adorno claims, still relies on the fact that some own and others do not own their means of production. Further, Adorno argues that even though industrial capitalism has changed insofar as the means of production have become administrational and increasingly mediated through culture, it does not mean that capitalism’s ability to produce surplus-value has stopped. Rather, he says, the capitalist system has become more sophisticated in upholding a “technological curtain” functioning as an illusion of the real conditions of production. Whether we go with Streeck’s claim that capitalism is about to disintegrate from within, or whether we take Adorno’s argument to still hold (that capitalism continues with business as usual although in new cultural forms) the artwork’s role must be to reflect these crisis-ridden illusionary states through its own specific forms.

[1] For the philosophical and institutional development of the concept see Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984[1974]). For an account of its practical and institutional implementation see Pierre Bourdieu, The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, trans. Susan Emanuel (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1996 [1992]). For some accounts of modernity as a complex historical moment see Michel Foucault, History of Sexuality, Trans. Robert Hurley (New York: Vintage Books/Random House, 1978) and Gayatri Spivak, A Critique of Post-Colonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present (Harvard UP: Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1999).

[2] Hanno Rauterberg, Wie frei ist die Kunst? Der neue Kulturkampf und die Krise des Liberalismus (Suhrkamp: Berlin, 2018) and Mikkel Bolt Rasmussen, After the Great Refusal - Essays on Contemporary Art, Its Contradictions and Difficulties (Pennsylvania: Zero Books, 2018).

[3] Robert Brenner, Economics of Global Turbulence (London/New York: Verso 2006 [1998]), xxiv.

[4] Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2017).

[5] Wolfgang Streeck, How Will Capitalism End? Essays on a Failing System (London/New York: Verso 2016), 13.

[6] Rasmus Fleischer, “Värdekritisk kristeori: A tänka kapitalets sammanbrott” in Fronesis #46/47 (Summer 2014), 89. (My translation into English from Swedish).

[7] See for example Nancy Fraser, “Contradictions of Capital and Care” in New Left Review #100 (July/August, 2016), 99–117.

[8] Peter Osborne, “Notes on form” in Thinking Art: Materialisms, Labour, Forms, ed. Peter Osborne (Kingston Upon Thames: CRMEP Books, 2020), 160.

[9] Bolt Rasmussen, After the Great Refusal and Leigh Claire La Berge, Wages Against Artworks: Decommodified Labor and the Claims of Socially Engaged Art (Durham/London: Duke UP 2019). By ‘decommodified labour’ she means, “a kind of work that is not compensated through a wage or available through a market purchase. Nor does decommodified labor primarily derive from or circulate through the intimate settings of family care, and love, a kind of work increasingly recognised as affective labour.” (4)

[10] Marina Vishmidt and Kerstin Stakemeier, Reproducing Autonomy: Work, Money, Crisis and Contemporary Art (London: Mute Books, 2016).

[11] Bolt Rasmussen, Art After the Great Refusal, 17.

[12] Bolt Ramussen, Art After the Great Refusal, 13.

[13] Sven Lütticken, Cultural Revolution: Aesthetic Practice After Autonomy (Berlin, Sternberg Press, 2017), 7.

[14] See for example Antonio Negri, “Metamorphoses” in Radical Philosophy #149 (May/June 2008), trans. Alberto Toscano, 21-25.

[15] Leigh Claire La Berge makes a good critique of both these positions in her book Wages Against Artworks, 20-27.

[16] Barbara Cassin, ed., Dictionary of Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon, trans. Emily Apter etc. (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton UP, 2014 [2004]), 349.

[17] Osborne, “Notes on Form”, 167–168.

[18] Rodolphe Gasché, The Idea of Form: Rethinking Kant’s Aesthetics (Stanford, California: Stanford UP, 2002).

[19] Osborne, “Notes on form”, 171.

[20] Peter Osborne argues that although Hegel’s understanding of form as self-moving content works well with historical forms of capital, we still must criticize Hegel’s metaphysical concept of art as sensuous semblance.

[21] Nicole Pepperell, Disassembling Capital, PhD. Diss. (Melbourne: RMIT University, 2010), 1.

[22] Karl Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy (Rough Draft), Trans. Martin Nicolas (New York/London: Penguin Books, 1993, [1973]),100-109.

[23] Patrick Murray, The Mismeasure of Wealth: Essays on Marx and Social Form (Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2016), 1.

[24] Murray, 4.

[25] Gillian Rose, The Melancholy Science: An Introduction to the Thought of Theodor W, Adorno (London/New York: Verso, 2014 [1978]).

[26] Stewart Martin, “Adorno’s Conception of the Form of Philosophy”, Diacritics, Vol 36, No 1, (Spring 2006), 48.

[27] Rose, The Melancholy Science, 16.

[28] Theodor Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, trans. C. Lenhardt (London: Routledge, 1984, [1970]), 8.

[29] Frederic Jameson, Marxism and Form: 20th-century dialectical theories of literature (Princeton New Jersey: Princeton UP, 1974), 5.

[30] Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 7.

[31] Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 2.

[32] Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 7.

[33] Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 4.

[34] Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 10.

[35] Robinson, Adorno’s Poetics of Form, 44.

[36] See for example Peter Osborne, “Notes on Form” and Murray, The Mismeasure of Wealth.

[37] Robinson, Adorno’s Poetics of Form, 44 and Rose, The Melancholy Science, 144.

[38] Adorno, Aesthetic Theory, 315.

[39] Friedrich von Hayek, “The Use of Knowledge in Society”, The American Economic Review, Vol. 35, No. 4. (Sep., 1945), 519-530.

[40] Theodor W. Adorno, “Late capitalism or industrial society? The Fundamental question of the present structure of society” in Can One Live After Auschwitz? A Philosophical Reader, ed. R. Tiedemann; trans. R Livingstone and Others) (Stanford CA: Stanford University Press 2003, [1968]), 111.

[41] Adorno, “Late capitalism or industrial society?”, 111.

[42] Adorno, “Late capitalism or industrial society?”, 115.