Putting The Body In The Place Of The Soul, What Does This Change?

Nietzsche between Descartes, Kant, and Biology

By Barbara Stiegler

The fact is well known: in choosing the body as his guiding thread, Nietzsche lays claim to a starting point deliberately opposed to the one selected by modern philosophy since Descartes. Whereas Descartes started out from the soul, Nietzsche will begin from the body – from the body growing and conserving itself, from the living body (Leib) of the physiologists, and not from the calculable and inert body of the physicists (Körper) – from that whose study Descartes thought he could postpone until later. For, in the title of the Second Meditation, that “(my) mind is easier to know than (my) body,” we should hear that the spirit comes first, not only with respect to the res extensa that makes up the inert bodies (Körper), but also with respect to my own body, the living body that I am, my own organized flesh (Leib). As long as the cogito lasts, my own living flesh, this organized, articulated, and complex body that I am, is in fact only a doubtful portion of the world – thus something wholly other than me, and this in spite of the interrogations of the last Meditation (am I not, finally, my own body?) that will, but only later, to a certain extent complicate this inaugural situation. In this sense, putting the living body in the place of the soul means to reverse the starting point of modern philosophy.

Nevertheless, in order to justify this substitution, Nietzsche provides two reasons which immediately underscore his dependence on the Cartesian starting point: if the living body “should be placed first methodically” (KSA 1886–87 [56]), this is 1. because it is a clearer (deutlich) and graspable phenomenon – a privilege of clarity and distinction already suggested by the (Cartesian) reference to the method, and 2. because we “thereby get an exact representation of our subjective unity” (KSA 1885 40[21]). In this way, as for Descartes, philosophy remains subordinated to the question of subjective unity – to the question of knowing what it is to be a subject capable of experiencing itself as one, and to call itself an ego. Even if philosophy this time starts with the body, it still starts methodically with the subject’s “exact representation” of itself. This self-representation still passes through the methodological value of the clear and the graspable, and the subject of the method deliberately ignores all that which remains in the shadow, outside of its gaze and out of reach.

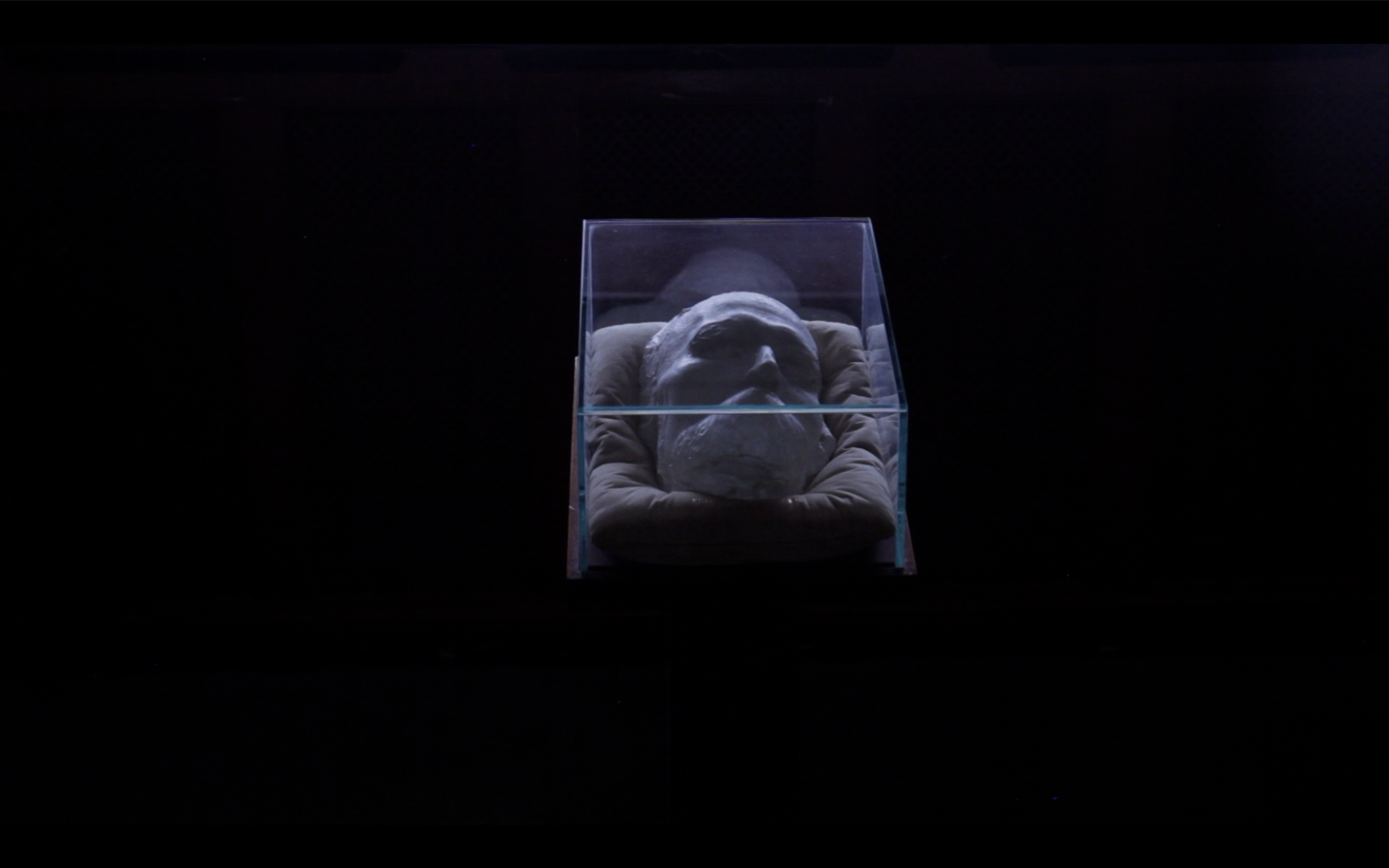

Joakim Forsgren, Dark Matter, Golden Door, 2019 detail, 3D scan of what might be the scull of Descartes. Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger.

This simple reminder suffices to question the naïve idea according to which Nietzsche, in putting the body in the place of the soul, would suddenly have liberated himself from the modern beginning, in opposing Cartesian rationality, sure of itself and essentially occupied with dominating the world through calculation, to a whole new world – the subterranean world of the body, the incalculable reign of drives and affects, hitherto ignored and denied, and which now, finally, would have been recognized and taken into account by philosophy. Not only, when we scrutinize the matter more closely, is the body a clear and distinct phenomenon, a methodical and graspable starting point (more than an obscure, invisible, and unthinkable drive), but also it seems to inherit the distinctive features of the Cartesian ego. For in what, essentially, consists the activity of the living body according to Nietzsche? Attentive to the response of the biologists, Nietzsche retains the idea that the essential thing about the Leib, in relation to the Körper, is that it feeds and digests; that it assimilates, that it renders identical (ad-similare), that it returns things to the same. In this it is in no way different from the cogitating ego. The end of the Second Meditation defines the cogitating ego as that which judges what it feels to be the same (I always feel a piece of wax in different ways, but I judge it to be the same). To be an ego, in this final version of the cogito, is to will identity in a sovereign way, starting from oneself, it is to decide to bring back all that one senses to the identical, to reduce everything to oneself and to the same, and to set up for oneself a stable world of subsisting things and calculable objects. But the conscious ego is for Nietzsche here no more than a particular case of the interpreting body (KSA 1886–87 5[65]). All that lives makes things identical (assimilation) and brings things back to itself (appropriation). Descartes’s ego is nothing other than its body: it is only a particular case, an instrument, an organ of the living body.

The death mask of Friedrich Nietzsche. Photo: Juan-Pedro Fabra Guemberena

But the body in Nietzsche might itself also be a sort of ego. Since the substance (that which remains identical in “things”) is a consequence of the subject (KSA 1887 10[19]), all rendering-identical (all perception of “things,” “objects,” and “substances”) already presuppose the subject. The assimilating body is thus only a new figure of the subject, and Nietzsche does not hesitate to interpret it, not only as a “consciousness” (KSA 1884 25[401]), as a “psychical” and “intellectual center” (KSA 1886-87 5 [56]), as the “subjective activity” of a “sensing, willing, and thinking” subject (KSA 1885 40[21]), but also as an “individual spirit” and as “spiritual I” (KSA 1884 26[36]). This makes it justified to question the radicality of the Nietzschean overturning. If the body is the same as the ego (conscious, sensing, willing, and projecting onto things an identity that comes spontaneously from itself), and if it grasps itself in the same mode (representation, clarity and distinction, method), then, putting the body in the place of the ego, what does this change, fundamentally? For Heidegger, who perhaps most clearly of all saw how much the body in Nietzsche owed to Descartes’ ego, this changes nothing, fundamentally. “That Nietzsche puts the body in the place of the soul and of consciousness changes nothing in the fundamental position established by Descartes.” (Nietzsche II, s. 187)

We could have stopped here if the body for Nietzsche was only this: nothing but the thinking ego, willing and experiencing itself as an I. But by “body” Nietzsche does not only mean the sensing of the self, the source of “I-ness,” the sensing (or the representation) of oneself as one sole individual. In order to prevent such a misunderstanding, he quickly added that the body he dealt with was not the ego, but an articulated and complex ego-collectivity: an organism sensing and experiencing itself as many (KSA 1885 37[4]). For, in reality, there is no such thing for Nietzsche as a living being or a body that could be reduced to the simplicity of the ego. The smallest cell is already an organism, already a plurality of articulated organs, already an ego-collectivity. Every I, if it is corporeal, first and foremost experiences itself as a We. But on the basis of this, the three determinations of the body which seemed Cartesian (1. a clear phenomenon graspable by the method, 2. an instance which is one and identical, 3. judging and assimilating: performing its own identity in rendering everything else identical to itself) has to be reevaluated.

In order to do this, let’s start with the first point: the body as a clear and graspable phenomenon. If Nietzsche rethinks the Cartesian value of the clear and the distinct, he on the other hand rejects the privilege of the simple. The phenomenon of the body has to be put first in rank, not because it would be more simple, easier to grasp and understand, but on the contrary because it is more diverse, more complex and rich: “the study of the body provides a concept with an unspeakable complexity” (KSA 1885 34[46]). But ”it is methodologically permitted to utilize a richer phenomenon [---] as a guiding thread to understand a more poor one” (KSA 1885–86 2[91]). Here the method does not start from the most graspable and the most clear, in the sense of the most simple and easy. It starts from the most striking and rich, from the phenomenon which yields the most to think precisely because it surpasses and exceeds what we are already capable of thinking and grasping (the simple, the simplified). The phenomenon of the body is not a conceptualized object, constructed and grasped by the body (a simple and thus “poor” phenomenon). It is a phenomenon which gives itself to us by imposing its richness, its complexity, its “prodigious diversity,” which does not prevent it from being more graspable and clearer, in the sense in which delineated evidence is more crisp and more clear-cut than a presupposition.

In this sense, we become more gripped and surprised by the body, “miracle of all miracles,” which brings philosophy back to its first affect – astonishment (KSA 1885 37[4]) – the more we take ourselves to be the first object of its method. But why then continue to speak of method? Exactly in the sense in which Husserl some years later, in § 24 in his Ideen, would affirm that “the principle of principles” of the phenomenological method is to have no principle and to acknowledge every “originary giving intuition” as a “source of right.” It is only in this that philosophy can separate itself from simple assimilation (cellular or logical), that it becomes something more than nutrition and digestion bringing things back to the same (constitution of objects or production of things, characteristic of the natural attitude and of vital activity), that it becomes a deliberate search for that which resists assimilation, a pleasure taken in the problematical, or in that which in phenomena exceeds our comprehension. Contrary to the Cartesian point of departure, the method starting from the phenomenon of the body starts from that which resists our methods. Without doubt it is here that Nietzsche opens a passage leading beyond the limits philosophy assigned to itself in its modern founding: if the body perturbs the modern project, this is less because it would be obscure, invisible, or unconscious, than because it, on the contrary, appears with a splendid evidence, like a surprising and marvelous phenomenon defying the assimilatory procedures already in place by resisting them.

Thereby, as we just have remarked, philosophy differs from the bodily assimilating ego. In reality, it discloses the secondary determination of all living flesh, which gives the first determination its sense and necessity. If the living body interprets, constitutes and brings things back to the same, if it assimilates and has to render identical, this is precisely because that which it encounters is first and foremost never similar. If the flesh brings back to the same and assimilates, it is because it has to feed on the other, which it itself is not. Strictly speaking, no living body can be autophagic or feed on itself. Nutrition implies an other, assimilation an excitation, regulation a derangement. In this sense, the irritability of the flesh, its capacity to be altered by another which it itself is not and which troubles it, is the very condition of assimilative activity, or even, as Virchow thought, the ultimate criterion of the living being: “Understanding is originally the suffering of the impression and the recognition of a strange force” (KSA 1883 7[173]). The body assimilates (understands, thinks and wills the same) since it is affected in different ways (since it always experiences different things): since it relates to a prodigious complexity whose unity and unification are to be attained.

In this way, the Nietzschean position of philosophy is that of the flesh itself: to be stunned by a prodigious diversity, to pose the question of its unification (how can it be assimilated and comprehended as a unity), this is the fundamental situation of every living body. In Nietzsche’s philosophy, just as in the body, the unity of the self is never given at the outset. It has no other status than that of a question: how the unification of the body would be possible, it is just this which is the problem (KSA 1885 37[4]). Not something given at the start, but a “problem.” Whereas Descartes started out, as does consciousness, from unity as given, or from the ego as a starting point (where the method had already given itself the subject), Nietzsche experiments with his body, a method where the only given phenomenon is the diversity of affects, a given which in itself calls for – as a question calls for a response – a subject to come, still undetermined. Since the philosophy of Nietzsche finds itself exactly in the situation of the living body, we can now understand the sense in which it is no longer the soul, but “the body that philosophizes” (KSA 1882–83 5[32]).

Emil Doerstling, Kant with friends, 1900.

The body philosophizes by taking the prodigious diversity of that which affects it as its point of departure. Philosophy begins here, just as Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason does: not by the active self-affirmation, or by the ego’s givenness to itself, but by the affection of an other, given and received in passivity (Transcendental Aesthetic, § 1: to think, one has to be affected). To this interpretation of the Nietzschean concept of affect, it could be objected that for Nietzsche, the affection of the body never is an affection by the other, but by the self through the self, an auto-affection or an active self-affection, ignoring all that comes from passive reactivity in alterity. To this objection, one could respond in two ways.

1. It is true that that which the body senses is always itself; it does not sense the other except in sensing what the other does to it. The “prodigious diversity” affecting the body has to be interpreted as an inner diversity, and the sensation of the diverse, as a sensation of the self.

But this is precisely what Kant affirms: the sensation of the other, of the given diversity, is at the same time “inner sense,” sensation of self, not as a self, but as something diverse. In this way the Kantian analysis of inner sense does not expel alterity from the self, on the contrary, it most definitely installs the other in the self: experiencing itself in an original and intimate way as diverse, the self experiences itself not as an ego or as a self, but as always other, as altered in an originary way, as a “prodigious diversity.”

2. Since the only given for the sensible and living subject is this fluent, ungraspable and diverse process which is itself, not only does it not know itself as one, but it also never experiences itself as already united (Jenseits von Gut und Böse, § 15; Zur Genealogie der Moral, Vorrede § 1). The only sense which subsists for the ego is to be a project, a fiction, a dread of the living subject (a paralogism). The cogito, even its most sensible and incarnate version (cogitare in the sense of experiencing oneself via auto-affection, in the sense of “sensing oneself sensing,” cf. Michel Henry, Généalogie de la psychanalyse, chap. 1: “videre videor”) is invalidated by Nietzsche with the help of arguments that are all borrowed from Kant. Thus, his refutation of the Cartesian “immediate sensation of self” shows that the affect, for him, cannot mean the active self-affection which excludes passive affection by the other: all affects, for Nietzsche as well as for Kant, are sensations of self as well as painful affection by another indissolubly, “the suffering of impression” and “recognition of a strange power” that resists.

But the originality of the Nietzschean critique of the cogito consists in performing a synthesis between Kants arguments against Descartes, on the one hand, and, on the other, the most recent discoveries in biology, a synthesis which allows him to extend the Kantian problem to all living beings. That which Kant reserved for human beings, affectability by a given diversity, given and received in passivity, Nietzsche and the biologists attribute to all living flesh. What is characteristic for the living flesh in relation to the inorganic particle, that which marks the frontier between the psycho-chemical and the biological, is its capacity for intussusception, its capacity to receive in itself the other-than-itself, its sensibility toward the other: its irritability. The inorganic bodies (Körper) collide and attack each other, avoid or destroy each other, but they never experience, suffer or nourish each other. Only the living body (Leib) is affected, touched, and overcome by that which is crosses on its path. And this is precisely because is takes the other into account, interiorizes it, grows from the inside, extends as a diversity and is articulated as a complex and multiple organism. Thus, all living bodies are sensible subjects. Sensibility is no longer understood only with a view to knowledge (to know, one has to sense), but as a condition of possibility for life.

Life is organic complexity, and the diversity of organs presupposes the aptitude to suffer and to endure the diverse within itself. What sense is there then to speak of the body as one organism, and to see in it “the exact representation of our subjective unity”? Here as well, Nietzsche returns to the analyses of Kant and fills them with a biological content: the body, like the subject, is not only sensible and diversely affected, it is just as immediately occupied with unifying that which it receives by bringing it back to identity: as a “prodigious diversity” it is also a “prodigious reunion” (KSA 1885 37[4]) of the diverse. But, if the Kantian subject is at once capable of sensing (a diversity) and thinking (or unifying), this is because it is only a modality of the flesh, at once irritable (sensible) and assimilating (thinking, bringing back to identity). Thus, the body of the biologists is indistinguishable from the Kantian subject: both irritable and assimilating, it seems, just as Kant’s subject, to be divided into two heterogeneous parts, one sensible and passive, the other active and thinking. But how can we in this way cut the living body in two, without losing sight of the cohesion by which all that lives remains alive? To bring the dualism of sensing and thinking back all the way back to the analysis of the body, does this not mean to negate, in a paradoxical way, that which is characteristic of corporeality and life the indissoluble bond between acting and suffering?

Furthermore, to attribute the spontaneous faculty of rendering identical to the body isn’t this necessarily, according to Kant, to constrain oneself to ascribe to it not simply an already unified ego, but which is even worse, the most disincarnated version of the subject: the pure logical form of identity (the I in the sense of A = A)? If this were the case, the astonishment in front of the given diversity would finally be lost again, and the auto-positioning of the I in search of the stabilization of a world of identical objects in other words: the philosophical project of modernity would be fundamentally secured. Then Heidegger would, in the final instance, be right: to put the body in the place of the soul would finally not change anything in the fundamental position of Descartes and his project: “to see according to need and utility [---] predict, calculate and plan (Nietzsche II, 192). The Nietzschean body, as a direct descendant of the Kantian transcendental subject, and projecting spontaneously the objectivity of objects according to its own categories, would be no more than a version of the planning ego. The cogito would on the other hand at least have the privilege to hold on to its astonishment in front of the evidence of that which is given: if not the self as thing, then at least my own experience as it appears and makes itself felt, before every transcendent intending towards an object.

Heidegger skiing, 1920. Photographer unknown.

Nietzsche, just as Kant, interprets this appearance of the lived experience before itself as a fiction. Since the subject is originarily just as much a thinking thing as a sensing thing, all of that which it senses is already thought, already subjected to the assimilating categories of thought. This affirmation of a formation (Kant), or an originary deformation (Nietzsche), of the given by thought, this originary necessity of synthetically unifying a manifold, is interpreted by Kant as the condition of possibility of knowledge. In this sense, and up to a certain point, he thus interprets it as a condition of the modern project to install a world of objects to be planned. The paradox is that the initial thought to which the project of modernity can be attributed, the cogito, would finally be more free from its presuppositions, more deliberately open to that which gives itself, before all intentions, than its most famous critics, who in the last instance are more occupied with affirming the originary primacy of thought (or assimilation) over the given (or the senses).

In putting the body in the place of the subject, Nietzsche refutes already in advance such an objection. The biologizing of the Kantian subject discloses that the originary synthetic formation of the given by thought (Kant) is only a particular case of the originary scarring of the irritation by assimilation. If the living being is not only passive and sensible, but active as well, acting on the behalf of itself and its own identity, this is because it spends its life trying to cure itself (actively) from that which affects itself in suffering. As a wound begins to create a scar from the moment it opens, the living being is from the outset called upon to cure itself, always in search of its synthetic identity, precisely because it is constantly hurt by that which affects it. The question of synthesis (a term which already Kant borrowed from surgery) thus becomes, with Nietzsche, explicitly medical. But in incarnating the Kantian synthesis in a living body, Nietzsche sets himself apart in two ways from the modern project of the planning of being-ness:

1. The living flesh, in taking the place of the subject, can in no way take on the role of the consummately planning ego, not even that of a insensible, transcendental I, since it acts precisely where it is marked by passion, and cures itself through its very wounds.

2. Furthermore, what is at stake in synthetic unity can no longer be knowledge or the mastery of objects, but only life, and with the continuation and the maintenance of life, the capacity still to be affected.

Let us stop at the first point, which will lead us silently to the second: the assimilating I acts in the very place where it is passively affected. To do this, active assimilation and passive irritation, which are apparently heterogeneous, both have to be articulated on a common stage. Kant had already begun to disclose the nature of this common stage: for sensibility and thought to be mutually articulated, he showed that there must be, in the subject, an instance both passive and active, both impressionable and spontaneously creative. For him, this instance was the imagination, understood as the faculty of temporalization (cf. Kant and the Problem of Metaphysics: “The transcendental imagination is originary time.”) Once more, Nietzsche will perform a rigorous biologizing of this Kantian discovery: after the biologizing of sensibility (which becomes “irritation” or “excitation,” Reiz) and of the spontaneity of I think (which becomes “assimilation”), the time has come for their common root, imagination, to reveal its carnal and organic sense: if the human being subjects diversity to categories through an originary temporalization, this is because the flesh, for a long time now, has healed from its own wounds through memory. With the first living creature begins both intussusception and memory. (KSA 1884 25[514])

For memory is the capacity to retain in oneself the trace of the other (irritation), while subjecting it to its proper order (assimilation). With memory, the living being becomes capable of 1. ingesting the other, bearing and supporting the other in the self: sensibility as the painful presence of the other; 2. subjecting it to the old and recognizing it as the same: assimilation as the repression and submission of the new to the past, to the already there (KSA 1885 40[33], 40[34]); 3. finally, it becomes capable of accumulating in itself a repressed alterity, susceptible to resistance and a provider of rupture; this is memory as that which can only make possible the coming of a future (KSA 1885 36[22]). If the living being is the only being susceptible to growth, evolution, and history, this is because only it can remember, because memory is the originary property of the flesh, a fundamental condition both of irritability and of assimilation, as of their mutual articulation. And if the body is at once the struggle of the diverse and ordering of the struggle, if only the flesh is capable of establishing a hierarchy of it is own inner diversity, this is because it is the only thing endowed with memory, with that interior scene where the passivity of diversity and its active ordering are knit together.

We can now understand why the interpretation of the will to power with the body as a guiding thread is an “attempt at a new interpretation of that which is coming” (KSA 1885 40[50], KSA 1885–86 1[128]). That which is coming can here no longer be interpreted as an accident that would leave the substance ego in place, nor as an empirical flux that would leave the transcendental subject intact. Instead of being an accidens of the ego or the subject, the “coming” becomes the very destiny of the living body, destined to search its own unity in risk of that which is coming. On the other hand, to understand the subject as already achieved (both as feeling and knowledge of the self, and as a logical function of identity A = A) means to propose that the subject would be there before anything else than itself had happened to it. Under these conditions, how can we continue to claim that to put the body in the place of the soul would not change anything in the fundamental position established by Descartes? As long as philosophy was instructed by the soul and by consciousness, it thought itself to be its own starting point and, at the same time, the authority which masters and plans what-is-to-come, and the I think was interpreted with the body as a guiding thread and discovered its “necessary relation to a knowledge coming from elsewhere” (Jenseits von Gut und Böse § 16), of which it is neither the source nor the planning authority. Thus, without renouncing the vital procedures of assimilation, without renouncing the duty of thought, of ordering and subjecting that-which-comes to its own categories and values, the philosophizing body will henceforth know that it, and its own power of assimilation are constituted in what arrives from elsewhere. If the body is still a figure of the subject and of the will, the will is here, perhaps for the first time, fundamentally affected by that which happens to it. But under these conditions, philosophy can no longer be reduced to a calculus of needs and profits of the ego: like the living flesh, it must be capable of surprise, fright, and astonishment in front of the prodigious power of that which happens to it, at the precise moment when it is trying to face up to it.

Putting the body in the place of the soul, finally, what does this change? By making the flesh philosophize rather than the soul, Nietzsche has less attempted to shape the obscure, an invisible reality of the drives, into an object, than to call clear and distinct thought back to its own source: if the body thinks can and should think this is because it always senses more than it thinks, and because it constantly suffers from that which it does not yet comprehend. A reminder called forth by the limits and intrinsic dangers of the modern project itself: since the philosophy of the soul has forgotten and denied that all which is the body does not stem from assimilation, it is only on the condition of this reminder, this call, that thought can continue to think without either threatening the very conditions of life, of irritability, or compromising the possibility, for it, to be what-is-to-come.

Barbara Stiegler is professor of philosophy at the L’université Bourdeaux-Montaigne. Among her recent publications are De la démocratie en pandémie: Santé, recherche, education (2021), and Nietzsche et la vie: Une nouvelle histoire de la philosophie (2021). The text was first presented as a lecture at the symposium “No one as yet determined what a body can do,” at Artnode, Stockholm, 2001, and published in Site no. 1 (2001).