(S)Talking Tafuri

Rixt Hoekstra

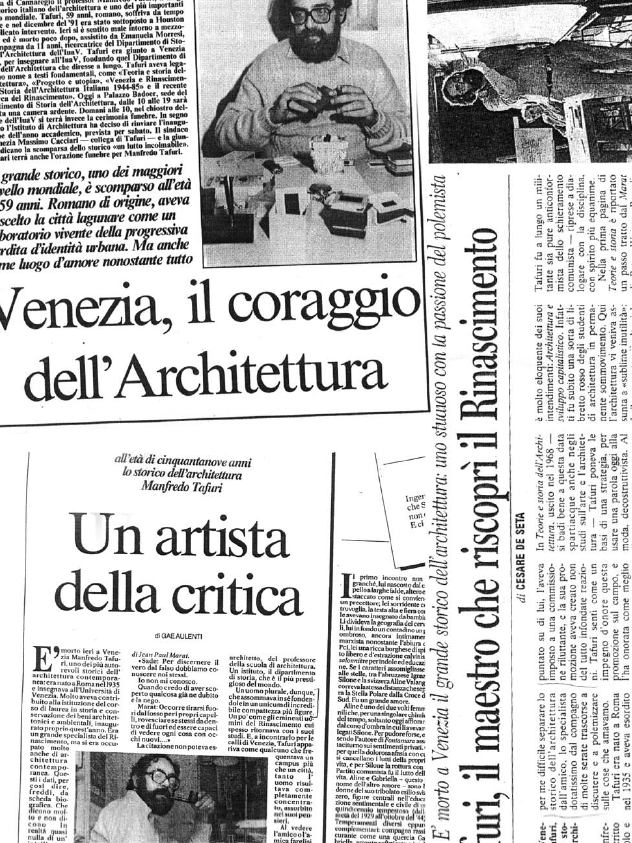

The American writer Mark Twain once wrote in a letter: “Rumors about my death have been greatly exaggerated.” This also seems to be true in the case of Manfredo Tafuri (Rome, 1935–Venice 1994) whose insights more than fourteen years after his death remain the subject of debate in architecture. The Italian architect and historian was one of most important architectural theorist in the twentieth century. The American historian James Ackermann described Tafuri as “probably the most influential architectural historian of the latter half of the twentieth century”.1 Yet during his lifetime Tafuri was also controversial and received fulsome praise as well as trenchant critique. Most of all, Tafuri was viewed as a typical Marxist historian who produced a leftwing outlook on architecture and its history. Today, in a world that has changed radically since the 1970s and 1980s, there seems to be every reason to bury the work of Tafuri along with him. However, following recent debates in architecture, the work of this historian seems anything but written in the past tense. If Tafuri remains topical, the question is: what causes this enduring currency?

Manfredo Tafuri, photographer unknown

Today, almost two decades after his death, Tafuri seems a haunting presence in architectural debate. His presence is haunting because he confronted the architectural world with a seemingly insolvable impasse: while, since the twentieth century, it has been an almost existential craving for architects to contribute to a better world with their designs, Tafuri has proved the historical untenability of exactly this enterprise.

Today, Tafuri seems to cast a dark shadow over each discussion of the possibility of architectural engagement. At present, his legacy is such that simply to speak about such an engagement almost automatically takes on pathetic characteristics, while the alternative of a “building without ideals” is, for many architects, just as unacceptable. This deadlock is also present on a theoretical level. For example, Tafuri and Dal Co’s thesis that the history of contemporary architecture should be viewed as “the record of an increasing loss of identity… in the wake of the enormous processes of socio-economic transformation”, has never been disputed nor elaborated by other architectural historians.2 While Tafuri uncovered a fundamental “crisis” at the heart of modernity, the suspicion and anguish generated by this insight seems to have never disappeared—it has only been repressed or denied.3 Since his untimely death at the age of fifty-eight, Tafuri’s legacy evokes an uneasiness. What is at stake is the ethical question of the responsibility to carry on Tafuri’s radical historical and critical project. Is it possible to reformulate Tafuri’s critical project? Is it desirable? Or should we by now accept the erosion and loss of a critical modus that is based in architecture?

In this article I will evaluate the legacy of Tafuri by focusing on the difference between the proverbial baby and bathwater. It is my contention that Tafuri should be admired for his analytical capacities with respect to architecture, and that his capacities remain unsurpassed in this area. Posing the question of the baby and the bathwater really means to pose the question of Tafuri’s program of architectural history and its enduring value. Was Tafuri a historical and contingent phenomenon or did he correct our understanding of architectural history in such a fundamental way that he simply cannot be ignored by anyone coming after him? In what ways can we think the presence of history in architecture, theory and architectural history after Tafuri? At the same time, there is another important debate connected to the legacy of Tafuri: this is the debate on the position of contemporary architecture in society. It is my contention that since the 1970s architecture has remained under the influence of two equally “extremist” visions on architecture: that of Tafuri and Koolhaas. Koolhaas in a way responded to the condition depicted by Tafuri, however, the question is whether the discourse of Koolhaas can be regarded as a form of radical critique of architecture and society in the same way as in the case of Tafuri.

Aldo Rossi, L’architecture assassinée, 1975, hand-painted etching for the cover of the American translation of Progetto e utopia (1976)

Tafuri: Local or Universal?

In an interview, Nikolaus Kuhnert, editor-in-chief of the German architectural journal Archplus, reflects on the translation of Progetto e utopia, Architettura e sviluppo capitalistico into German in 1977: the book received the title Kapitalismus und Architektur, von Corbusiers “Utopia” zur Trabantenstadt (Capitalism and Architecture, from Corbusier’s “Utopia” to the Satellite City).4 In the interview Kuhnert recalls his first encounter with Tafuri. This was in the middle of the 1970s, during a period in which the editorial team of Archplus developed an interest in the first manifestations of postmodernism in the Italian architectural scene, for instance in the debate on typology, or in the architect Aldo Rossi. Kuhnert and his team went to Venice to meet with Tafuri. As he recalls, this was quite a peculiar experience, with Tafuri sitting in a large room behind an equally large table, like the traditional Italian professor. To his left and right, standing, were his assistants and at the back of the room there were many books—all translations and compilations of the German discourse on modern architecture from the 1920s. Whereas in Germany this discourse had completely disappeared from view in the decades after the war—a consequence of Germany’s troubled past—here it was studied again and in a completely new and surprising manner. Beyond the polarized debates of the political left and right, a group of Italian intellectuals offered a compelling new outlook on Germany’s modern architectural and intellectual past. However, at the same time Kapitalismus und Architektur may be called representative for the average Tafuri translation: quite a lot is lost in translation and the German reader had a difficult time capturing Tafuri’s message. Despite Tafuri’s study of German modern architecture, this translation never led to a wider debate—not even in the circles of Archplus. In the German architectural discourse, Tafuri was never a presence. This is surprising for the reason, among others, that Tafuri would have fit in quite well within the intellectual discussion on the left, especially in the context of the rediscovery of the Frankfurt School in the circles of the German student movement. However, at least until the middle of the 1980s, German architectural discourse lacked the theoretical context to do justice to Tafuri. Instead, there was, in Kuhnert’s words, “debating with the hammer”: a polarized and politicized discussion on the right- and leftwings of architecture.5

During a conference held in New York in 2006, American architectural theorist Diana Agrest reflected upon her first meeting with Tafuri.6 This also happened in the 1970s. Tafuri was still a relatively unknown young Italian scholar, who, because of his Communist affiliation, had trouble obtaining a visa for a trip to the United States. Tafuri was invited by Agrest and her colleagues Mario Gandelsonas and Anthony Vidler from Princeton University because it was their aim to introduce a critical discourse in architecture. “Critical” for them was synonymous with “struggle”, as a direct application of new theoretical and political insights in the fight for political and social change. While this meant an absolute break with the then prevailing interpretation of the International Style as “aesthetic surface style”, for Agrest and her colleagues, an unproblematic return to the classical doctrines of modernism was just as impossible. Tafuri was heralded as a European scholar able to provide a new insight into European architectural modernism, balancing both militant engagement and disenchanted knowledge. While Agrest and her colleagues experienced New York in the 1970s as a city in crisis and as a chaotic, un-ordered explosion of fragments, Tafuri wrote about the “crisis of the object” and about the end of the organic, complete form.

Marxism in Venice. Picture postcard, unknown artist, 1983

Some twenty years later I met Tafuri in a classroom in Venice. I was part of a group of international students who had the privilege of being in Venice as Erasmus exchange students. Tafuri seemed physically weak, but very strong in his analyses of architecture. In 1994, the year in which I participated in Tafuri’s course, the Berlin Wall had already been down for five years. Fifteen years earlier Lyotard had published The Postmodern Condition (1979), declaring the end of grand narratives: for us there was no longer a clear separation between the political left and right. For most of us this was the first time we explored the scientific legacy of the 1960s and 1970s, the first time we studied neo-Marxism and its relationship to architecture. We were impressed by the engagement of the intellectuals in this period; in comparison, our own time seemed only too superficial. As Tafuri suddenly passed away that year, we also realized that from now on there would be a difference between the narrow understanding promoted by “Tafuri’s children” and our own generation. For us, exegesis alone would not suffice: studying the work of this historian automatically implied formulating a judgment on the durability of his insights for the future.

In the last few years a number of studies have appeared that stress the particular Italian circumstances in which Tafuri developed his body of work. In the dissertations of Leach (2005) and Aureli (2007), and also in my own dissertation (Hoekstra, 2005), the particularities of the Italian political and cultural landscape are sketched in this way.7 These studies certainly have their strong points: they can be explained in light of the background of the fundamental misreadings of Tafuri in the past and the fact that his body of work has long been shorn of the context that once gave his voice its distinctive grain. At the same time, these dissertations foreground a meaningful tension. Is the value of this historian present in the genius loci of postwar Italy, or rather in the fact that he has transcended his national context to become important for a wide international public? In other words, was Tafuri a fascinating historical incident, possible then, under those circumstances, but also impossible to repeat? It is my contention that Tafuri should not merely be considered a historical phenomenon, entirely defined by his context. Rather, the basis for the “future of Tafuri” should be the universality of his program for a new architectural history.

The Nelsons, by Wes Jones. Cartoon published in Any, special issue, “Being Manfredo Tafuri,” 2000

Tafuri’s program

What was Tafuri’s program in architectural history? When Tafuri started to publish his main works, his capolavori, at the end of the 1960s, he single-handedly created a rupture with what was by then a well-established historiographic tradition. In publications such as Teorie e storia dell’architettura (1968) and Progetto e utopia, Architettura e sviluppo capitalistico (1973) Tafuri openly criticized historiographical giants such as Wittkower, Zevi, and Giedion, whose work remained a common point of reference for architectural theory and history well into the 1960s. In fact, what historians of modern architecture such as Nikolaus Pevsner (1902–1983) or Sigfried Giedion (1888–1968) had in common was that they worked from a moral conviction about the place of architecture in a modern world. Fueled by a belief in progress, this was the central leitmotif behind their writing: the historian writing about modern architecture also identifies with the modern architect. If the architect builds for a better world, then the historian should reflect this ambition in his history, for instance through the choice of buildings discussed, for example. The architectural history that resulted from these attempts was optimistic in nature, speaking about artistic revolution and about the modern architect as a hero. Tafuri however no longer saw it as his task to confirm the emancipatory trajectory of the Modern Movement. Independently from the agenda of the architect, Tafuri connected architecture to a certain ideological load. Not the confirmation of the ways of the modern architects, but rather to expose and critically analyze them as a form of modern ideology. Tafuri thereby introduced a discourse that was far more complicated and far more negative. In the 1960s, Tafuri introduced new references whose relevance for architectural discourse was at that time unknown. For example, in Teorie e storia dell’architettura he pointed to the work of Roland Barthes, thereby proposing to see architecture as a system of signs that, just like literature, photography or cinema, was essentially an attempt to give meaning to the world around us—an operation which always to a certain degree failed. Tafuri invented new, puzzling tropes with which to reflect on modern architecture: “operative criticism”, “the ideology of architecture” or “regressive utopia”.

Once the identification with the goals of the architect was left behind, Tafuri was preoccupied with one principal question: what is modernity and what is the role played by architecture in modernity? How can the constant tension and implicit conflict between architects and their own time be explained? The concept of the Metropolis—or “the postulate of the intrinsic negativity of the large city”—became central to Tafuri’s understanding of modern architecture. “Metropolis” did not simply apply to modern urban experiences of constant speed, innovation, and change; in Tafuri’s writing the Metropolis had an additional value, as it was raised to the status of a theoretical category. For both Tafuri and Massimo Cacciari, “Metropolis” was the figure for the life of capitalism, as the general form for the rationalization of social relations. Modernity is Metropolis. The rational-capitalist system only has one place, and that is the Metropolis. In 1973, the year of the publication of Progetto e utopia, Tafuri’s friend, the philosopher and political activist Cacciari, published the book Metropolis—Saggi sulla grande città di Sombart, Endell, Scheffler e Simmel.8 It was, claimed Cacciari, German sociology at the start of the twentieth century that first captured the exact consequences of modernity. The Metropolitan world consists of abstractions in which the process of rationalization and intellectualization is totally dominant, from economics to politics to everyday life. In “Die Grossstädte und das Geistesleben”, Simmel points to the consequences of this reality. It is a ruthless process that is described by Simmel. He claims that the monetary market economy of the modern Metropolis is not only decisive for the exchange of goods, but also defines the norms of human behavior. This is the ultimate consequence of total rationalization: calculation, reason and interest had reached beyond the experiences of working life and invaded the most intimate pores of daily material and psychic existence. In this way, Tafuri and Cacciari tried to capture twentieth century modernism as a complexity of societal processes, of contradictory manifestations, from which nothing could escape. They tried to name capitalism at a certain stage of its development, where it displayed its most widened social effects, its impact on individual consciousness and the “colonization of everyday life”. They were therefore prepared to take the idea of rationalization much further then such thinkers as Lukács or Weber were prepared to go. Just as in the monetary system, claimed Cacciari, where the value of products is decided by their monetary exchange value and not by their intrinsic quality, so also in the interaction between people, the unique character of psychological experience is disregarded in favor of a notion that measures each human being according to her place in the system. This has as an important consequence that the city, conceived as a polis, as an organic unity, has been destroyed. From now on, it can only figure discursively as a lost ideal, as a nostalgia for plenitude, totality, and the integrity of values. Such is the new Metropolitan condition according to Cacciari. For Tafuri, the challenge was now to position architecture as ideology within this fully rationalized capitalist system. Cacciari, in Metropolis, had already claimed that the process of the interiorization of money circulation was counteracted by an opposing movement. Der Mensch ist ein trostsuchendes Wesen: Cacciari suggested that, in order to function in the modern, anonymous life of the big city, it was necessary to let one’s Gemüt, or heart, come forward every now and then. This was by no means an escape from the Metropolitan condition, but rather a form of irrationality that was completely functional to the rationality of the system. Cacciari thus essentially claimed that in a modern world architecture had become a matter of Trost, of consolation: an archaic, nostalgic experience and a form of ideology. Both Cacciari and Tafuri tried to find out the exact working of this ideology, its exact functionality to the system in various historical periods. As critical intellectuals, they saw this as their task. Architecture could not transcend the level of ideology, just like the new blasé inhabitant of the Metropolitan world could buy commodities but could not “get close to these goods, he cannot name them, he cannot love them.”9

In Tafuri’s account of modern architectural history, many of the well-known discursive parameters elaborated by historians like Giedion and Pevsner were preserved. Its revolutionary character does not derive from a presentation of a completely different history; the well-known tropes of modern architectural history are given a completely different meaning. For example, like many of his predecessors, Tafuri placed an emphasis on the position of the twentieth century avantgardes as groundbreaking for a completely new form of art. However, he gave a completely different interpretation of these avantgardes—an interpretation which is closely connected to his assumptions about the nature of architectural history. For both Tafuri and Cacciari, the Metropolis was not an agglomeration of static, built objects. Rather, these built entities were understood as a condensation of social processes, as petrified residues of social events. For Tafuri, the challenge of architectural history was to bring meaning to the material artifacts of architecture by providing them with a sense within the broader context of social, political, and artistic history. It is also in this perspective that we may understand Tafuri’s view of the avantgarde. For Tafuri they were “agents” in the internal reconfiguring of capitalist social relations in the early decades of the twentieth century. They thought of completely new forms of making art or designing buildings because they felt the need to sweep away older modes of being. In an indirect way, so Tafuri claimed, they thus reacted to the arrival of a “new economic form”. However, while Pevsner and Giedion, as well as Zevi and Benevolo, had welcomed the “cheerful alienation” of the avantgardes as forerunners of a new era, Tafuri was engaged in a completely different intellectual operation. Where Benevolo, for example, had pointed to the “flowery socialism” of William Morris as a precursor of modernism and as such as a desirable cultural policy, Tafuri depicted the tormented passages of “architectural ideology” as it developed in the twentieth century. As a consequence of the coming about of a “new economic form”, artists and architects felt their work was becoming increasingly a reification and social abstraction. To fight this tendency, they broke with tradition and introduced radical new forms: this was an effort, so Tafuri claimed, to break away from social abstraction and to reconnect to life. This is what Tafuri calls the inherent contradiction of the avantgarde: while the invention of radical new forms of art could only separate the artistic avantgardes from reality—think of the assemblages of Dada or the “disarticulated recompositions” of De Stijl—in the end this was only a form of réculer pour mieux sauter, as this separation only served the purpose of rejoining reality, of affecting reality in a way that conventional art no longer could. However, Tafuri argued, in the end this operation could only fail: through their alienated, radical forms, the avantgardes ended up reaffirming the tragic condition they had sought to transcend. The avantgardes were therefore an important example of the central illusion of architecture-as-ideology: the belief that design could not only make a difference at a social level, but that it could also withstand the conditions of the Metropolis, that it could resist its tendency to intellectualization and rationalization.

An important element of Tafuri’s history was the way in which he related the vicissitudes of the avantgardes to the political history of the first part of the twentieth century. This was an important part of Tafuri’s program: to identify the role played by architectural ideology within the three great ideological systems of the twentieth century—the realized socialism of the USSR, the social democracy of the Weimar Republic in Germany, and the capitalism of the US. For Tafuri, the “crisis of the avantgarde” was not a direct consequence of the political dictatorship in this period—again, a view that was completely different view from that of his colleague, the art historian Giulio Carlo Argan, who wrote the book Walter Gropius e la Bauhaus, emphasizing exactly this connection.10 For Tafuri, the rise of Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s USSR were in fact important events, but at the same time they were all different ideological reactions to the restructuring of capital and what Tafuri called “the realization of the modern economic form” as it happened around the year 1920. So they were all reactions to an epochal event that occurred during the first decades of the twentieth century, and Roosevelt’s liberal-capitalist America was also part of the same framework. In an analogous movement to politics, the artistic avantgardes now understood they could only survive the new condition by making the shift from utopia to plan. This, for Tafuri, was the central element of modern architectural history. Instead of the prefiguring of a new world, the avantgardes understood they had to take on the role of constantly intervening in, and organizing, reality. While for Tafuri the avantgardes were a complex and contradictory bunch, they were all faced with the same problem of finding the proper attitude to face the Metropolitan condition. As Tafuri wrote, the question for the avantgardes was “how to shake off the anxiety provoked by the loss of a center, by the solitude of the individual immersed in revolt, of how to convert that anxiety into action so as not to remain forever dumb in the face of it.”11

As a consequence of the arrival of a new economic order that supplanted stable values by “action”, anxiety over the Metropolis had to be exchanged for acceptance. If nobody could escape the condition of the Metropolis, then its contradictions had to be confronted in a productive way. Therefore, for example the Dadaist montages and collages were understood by Tafuri as a sort of repetition of the chaos of capitalist reality, but also importantly, as a means of reclaiming value from the ephemera of daily existence, exactly by a positive acknowledgement of it. The avantgardes were part of the same fabric as for example the economist John Maynard Keynes: as Tafuri explained, in reaction to the changed condition, he started to make plans starting from the crisis and not positioned abstractly against it.12 The challenge was no longer to stabilize economic conditions, but to work with conflict and contradiction, to manage the chaos of the modern world and make its crisis work for capitalism. As Tafuri wrote, it was necessary to work with the “negative… inherent in the system”. It was necessary to manage the transitory, the temporary, the oppositional, and contingent. As Gail Day observes, “the plan” for Tafuri did not refer to a fixed model but rather to the process of constant intervention in the system, aiming to absorb capitalism’s contradictions at ever higher levels. To study the role of architecture-as-ideology meant for Tafuri studying the different ways in which “the negative” was incorporated into the very process of social and economic development as capital’s power. Again, it is remarkable that Tafuri stays very close to the existing narrative of modern architectural history when he states that the avantgardes are marked by their anti-historicism. It was this liberating movement that, according to Tafuri, allowed the avantgardes to “explode towards the future”, to become activists and so to find a role within the emerging “planner-states” of the interwar years—the only possible way for them to survive.

Italian newspapers on the death of Tafuri

The future of Tafuri

What elements of Tafuri’s program still have value today? Since Tafuri’s rupture with the so-called “operative history”, architectural history can no longer be an apology for the great masters. Since Tafuri defined architecture as an “ambiguous object”, a piece of “Metropolitan Merz”, architecture has lost its status as a monument: an isolated object and as such a fetish, an idol. Tafuri has proved the untenability of the contention that architecture is an incorporation of the Good, True, and Beautiful.

From now on, to claim such a position for architecture means to repress or deny his insights. Instead, architecture for Tafuri became a “technique of control of the physical environment”: an element of power in an environment dominated by other elements of power. As a consequence of viewing architecture as ideology, political and social factors are no longer a context against which architecture positions itself; “architectural ideology” is an actor in a complex fabric made up of other social, cultural, political actors. From the study of individual monuments, architectural history has moved on to study the dynamics of processes, institutes, and techniques. However, at the same time it is the core element of Tafuri’s program that remains most controversial today: his shift from “positive” to “negative” or, better said, from “heroic” to “critical”. Tafuri has provided an alternative for an affirmative architectural history and has thus confronted architecture with a considerable critical burden. It is significant that this criticality did not find a continuation after Tafuri. While after Tafuri other forms of architectural history have appeared—histories that, for example, redirected the exclusive attention on the architect to a study of more anonymous cities and regions—it is a question of whether or not these histories are not still written in an affirmative way, as heroic histories of the progressive conquest of man over earth and of culture over nature. In the same sense, after Tafuri. a number of architects have appeared that seem to live according to Tafuri’s parameters. In particular, we may think here of Rem Koolhaas’s delirious immersion in the urban inferno. Koolhaas seems the perfect exemplification of life in the Metropolis: this architect not only accepts the harsh reality of the Metropolis, he also faces the negativity of it, he meets capital head-on and tries to outwit it.

However, the point of view from which one accomplishes such an action does make a difference: whether it is the legitimizing of late capitalism, as is the case with Koolhaas, or the development of a critique of it, as happened in Venice. Koolhaas still stands in the tradition of the modernist avantgardes: he studies the most intimate structures of modernity and then declares himself an advocate of them. Following the modernist slogan il faut être de son temps he takes modernity at face value. Here lies a fundamental difference to Tafuri, for whom the cultural expressions of modernity were a form of ideology: a deluding veil, an illusion, something that could very well be quite different from what it pretended to be. What presents itself as very modern can easily be a tradition in disguise and vice versa. It is here that the shift is made from mere description, or even analysis, to critical analysis.

Any consideration of Tafuri’s legacy should also take into account the fact that his reception has been problematic. The reasons for this troubled reception are equally significant for the future of Tafuri. In the first place, there is the impact of Tafuri’s pessimism, which had a paralyzing effect upon many architects. Books like Progetto e utopia were mostly understood as dire assessments of the possibilities of architectural practice. At the same time, Tafuri himself has always rejected apocalyptic readings of his work. However, it is the engagement proposed by him and his Venice colleagues, and the way in which this is embedded in the political atmosphere of the Italian far left, that remains the most obscure element of Tafuri. This new conception of engagement had its roots in the journal Contropiano: Materiali Marxisti. In this journal, Tafuri collaborated with intellectuals like Antonio Negri, Alberto Asor Rosa, and Mario Tronti. In the late 1960s, Contropiano was one of the platforms for the development of the political concept of operaismo and it was this concept that was at the basis of many of the shifts of paradigm executed by Tafuri. For example, there was the insight that in the labor-capital relationship it was labor that drove productive development, forcing capital to respond with defensive measures. Such inversions of the existing doxa were typical for Italian operaismo. As Gail Day observes, it is important to see a book like Progetto e Utopia as part of this very specific framework and not merely as a Marxist-inspired work that locates art and culture within the context of capitalist economy.13 This is important because what was at stake in the circles of operaismo was not just an assessment of the Italian society after the war, but a precise view on the nature of modernity itself.

Tafuri’s message was not easy for historians either. In the middle of the 1970s, when Tafuri wrote his capolavori, postmodernism in architecture was heralding the return of history as a serious factor in design. However, at the same time, Lyotard wrote The Postmodern Condition (1979), waving goodbye to the Grand Narratives and a universal understanding of history. Tafuri also broke with the Grand Narratives of his predecessors Pevsner and Giedion. However, instead of consolidating the newly achieved self-consciousness of the historian by providing a clean-cut historical methodology, Tafuri did the opposite. Tafuri’s work is characterized by a scientific and existential restlessness. It is a constant query into the nature of architectural history that at no point results in a “solution” or a formula to be used by other historians. Tafuri did not offer a hold for architectural historians, no models to be copied. To a certain extent, historians were left equally clueless after Tafuri. As a consequence, “history” nowadays seems to figure as an empty vessel in debates on architecture. While history has long been bereft of universal significance, few people in architecture ask the question: what history are you talking about, what is your understanding of history? This is not only a pity for those of us interested in history. A discipline that does not know its past does not know its future either. This seems an adequate description of the state of affairs in architecture today.

Rixt Hoekstra is an architectural historian and a Wissenschaftliche Mitarbeiterin at the Leopold Franzens University of Innsbruck.

Notes

1. Statement made by Ackermann during the conference The Critical Legacies of Manfredo Tafuri, Columbia University, New York, April 20–21, 2006.

2. Manfredo Tafuri & Francesco Dal Co, Architettura Contemporanea, Milan 1976. Translated by R.E. Wolf, Modern Architecture, 2 vols., New York (History of World Architecture), 1986, 3.

3. See Jon Goodbun, “The Assassin,” Radical Philosophy: A journal of socialist and feminist philosophy, July/August 2006, 62–64.

4. See Rixt Hoekstra, “Lost in translation? Tafuri in Germany, Tafuri on Germany: a history of reception,, Wolkenkuckuckssheim—Cloud-Cuckoo-Land, Journal for Architectural Theory, vol. 12, December 2008. Manfredo Tafuri, Kapitalismus und Architektur: Von Corbusiers „Utopia“ zur Trabantenstadt, ed. and translated by Th. Bandholtz, N. Kuhnert and J. Rodriguez-Lores, Hamburg (Analysen zum Planen und Bauen 9), 1977.

5. Ibid., 4 and 5.

6. Rixt Hoekstra, “Van tijdgeest tot kwelgeest,” De Architect, February 2007, 17–19.

7. Pier Vittorio Aureli, The Project of Autonomy: Politics and Architecture within and against Capitalism, New York, 2008. Andrew Leach, Manfredo Tafuri: Choosing History, Ghent, 2007. Rixt Hoekstra, Building versus Bildung: Manfredo Tafuri and the Construction of a Historical Discipline, Groningen 2005.

8. Cacciari, Metropolis: Saggi sulla grande città di Sombart, Endell, Scheffler e Simmel, Rome, 1973.

9. Gail Day, “Strategies in the Metropolitan Merz: Manfredo Tafuri and Italian Workerism,” Radical Philosophy, September/October 2005, 27. Quote from Cacciari, Posthumous People: Vienna at the Turning Point, Stanford 1996, chapter “Lou’s Buttons”.

10. Giulio Carlo Argan, Walter Gropius e la Bauhaus, Torino, 1951.

11. Manfredo Tafuri and Francesco Dal Co, Modern Architecture, part I, 105.

12. Gail Day, “Strategies in the Metropolitan Merz, Manfredo Tafuri and Italian "Workerism,” 31.

13. Gail Day, ibid., 33.