Swedish Heritage in St. Petersburg

The Policies of Remembering and the Practices of Oblivion

By Irina Seits

Heritage against history

When the names ‘Sweden’ and ‘Russia’ are mentioned in the same breath, their common heritage as a cultural bridge and as a source of inspiration for relations between the two nations today, is far from being assumed. They share a common yet divisive history of over a thousand years of military confrontation, which ended in the beginning of the nineteenth century. Since then, a far from complimentary image of the Russians has emerged in Sweden.

Russian Pillage (rysshärjningarna) of 1719 in Södertälje.

Photo by Oleksandr Polianichev, 2020.

Partially it was a remedy for the memories of irreparable damage that Russia caused to Sweden’s Imperialistic ambitions. These ambitions, in turn, have been long rejected by Sweden as a past worthy of commemoration. Long before other former European empires condemned their colonial backgrounds, Sweden had already developed a counter-narrative, promoting an image of the state as Folkhemmet – the home for all of its people and a shelter to those seeking protection. Hence Sweden sought to project ideas of inclusiveness rather than exploitation and colonization, preferring quiet social paradise over the image of a power player on the international political scene.

Sweden’s past has been ‘heritagized’ along the dual lines of (i) a politics of neutrality, something the country accepted two hundred years ago, and (ii) a prominent ‘third way’ ideology that avoided both unregulated capitalism and state communism. The heritagization of the origins of these choices have sought to make more tangible and visible the connections between Sweden’s history and the myth of the country’s ‘national’ character. Driven by this Swedish heritage, today’s political and social agenda in Sweden further ‘naturalizes’ these connections. Political perceptions of Swedish exceptionalism as of one of the world’s few moral states, which, on a humanitarian mission, dared to prioritize domestic affairs for the sake of its citizens’ well-being precisely when the rest of Europe was struggling for hegemony in the region.

The final wars between Russia and Sweden, resulting in 1809 with Sweden losing Finland, nearly a quarter of its territory, to Russia, pushed Sweden into choosing political neutrality and withdrawing into itself. Both choices, it could be said, were effects of the trauma of defeat. The country managed to benefit from this trauma, and in less than two centuries became an exemplary representative of the so-called ‘Scandinavian model’. Sweden thus became not just a role-model for Russia with its failed socialism, but for the whole world as well. Sweden understands itself as constituting the very yardstick by which social justice and fairness are measured, claiming to keep its citizens in a high standard of living, much to the envy of other nation-states, both near and far, whose greedy ambitions for global domination are pursued off the backs of their own people.

This tidy and well-ordered historical narrative is well worth interrogating. Specific historical events can be identified that do not fit within this ideological and political picture. Events that produce a certain amount of dissonance and make for less comfortable reading. In such cases, the heritage elaborately carved out of history is both a help and hindrance; it is on the one side a concealer of the ambiguities that stick to the histories we want to remember and, on the other, is marked by obscene protrusions, reminders of what we would otherwise wish to forget.

Heritage is administered, in contradistinction to history that in turn is understood as a domain within which some evidences of truth reside. Some twenty years have already passed since David Lowenthal, a prominent scholar of heritage studies, outlined a ridge between history and heritage in his book The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History.i Today, with two decades of the general pursuit of the total commercialization of heritage into the tourist industry, the line of distinction separating them remains none other than an axiom and common place. Even if the line separating heritage from history is subject to the logics of marketization and instrumentalization itself, and while, as Lowenthal writes, “these two routes to the past are habitually confused with each other,” his definition of the difference between the history and the heritage remains relevant:

In fact, heritage is not history at all; while it borrows from and enlivens historical study, heritage is not an inquiry into the past but a celebration of it, not an effort to know what actually happened but a profession of faith in a past tailored to present-day purposes.ii

The heritagization of the past goes hand in hand with its mythologization and stereotypization. This especially holds when this past is unavoidable at the same time as it is unworthy of celebration. Heritagization is a way of representing certain moments in history that comply with ‘present-day purposes.’ Even though such heritagization may distort history, it can articulate ‘appropriate’ episodes, as in a montage, to produce a continuity necessary for a historical narrative that serves the function of ‘good,’ ‘moral,’ and ‘just’ purposes.

Heritage highlights what is the most important and conceals what is the least convenient or relevant for the moment; it is as much about inclusion of what must be celebrated as much it is about excluding what is to be forgotten, as Lowenthal notes: “what heritage does not highlight it often hides.”iii

Heritage does for the representation of history what montage does for a novel narrated in a film. A promotional video, a booklet, or a website of, for example, a city or a country draws on their fragmented historical sites that represent these cities or countries based on their most positive sides, with the aim to attract and with the promise to provide great memories and unforgettable experiences, and hardly ever with the goal to turn away or to evoke a rush to ‘un-see.’ Appealing episodes extrapolated from the celebrated history and then glued back together in a purposeful sequence, represent an interpretation of this past and its edited version. These montaged historical narratives are then institutionalized and legitimized as heritage by museums, galleries, national parks, tourist routes, school textbooks, and popular shows.

The practices of heritagization of a national past inevitably face various ethical issues, such as the threat of being perceived as offensive, as well as the risk of misinterpretation. The politics of heritagization always deal with the revision of the past, with coming to terms with the past, and, sometimes, even with the pressure to apologize for it. The simplest way to bypass all these uncomfortable problems of a national heritage, followed ubiquitously by most states, is merely to montage them away from the narrative: “hence we practice oblivion,” as Lowenthal concludes.iv

The practices of forgetting and oblivion that I address in this essay, prove to be as closely connected to the heritagization and as massively applied to the representations of history and collective memory, as the practices of preservation, commemoration, museumification, promotion, and restoration are connected to the administration of what we believe is our authentic and true history and heritage.

While commemoration is a practice contraposed to exclusion, they are both actively employed practices of heritagization that do not necessarily contradict either remembering or forgetting history. Lowenthal dedicates a separate section of his book to the techniques of “exclusion”. There, he states that in referring to an episode described by the poet and novelist Hans Magnus Enzensberger in his Europe, Europe: Forays Into a Continent from 1990,v where a Norwegian traveler is surprised that the whole period of Swedish imperialist history is excluded from the exhibition of the Stockholm’s historical museum, Lowenthal states that “blanket oblivion is indefensible”:vi

“Fear of the past that might not fit into the self-portrait [Swedes] would like to draw” is held to explain the two-century hiatus in Stockholm’s historical museum; after the Vasas, approved historical memory seems to start again only with the 1870s, omitting the saga of Swedish imperialism, chiding Swedes for this “liquidation of their own history,” a Norwegian asks, “How can such an old nation know what it’s doing if it doesn’t know what it has inherited?” In fact, Swedes know what they inherited; it is in their history books. But it is not a legacy they wish to commemorate.vii

This exhibition at the Stockholm historical museum, as it turns out, did not serve the purpose of history – to tell us what had happened. Rather, it served the purpose of heritage – to commemorate and to celebrate what was right for producing a legacy, not for the restoration of facts reintegrated into a continuous historical narrative. This exhibition did not lie about Sweden’s past, it just chose not to tell about it. What was not in the exhibition in this case contributed to what was there in a process of producing a mythologized image of Sweden.

The material objects at the exhibition were historical artifacts that were selected and arranged in a certain (‘proper’) way to produce an image that the viewers could take home from the museum as an image of Sweden and as a memory of Swedish heritage. Hence this exhibition converted historical artifacts into objects of heritage that, even though related to Swedish history, were recontextualized within the coordinates of current state ideology.

Both politicization and ideologization of the past are essential tools of heritagization. Historical artifacts alone, even if they say something, do not mean much, unless they are explained, evaluated, and placed in a certain context and generalized as a part of a larger narrative. As viewers, we need to be told that these are important artifacts, thereby making them parts of the larger national heritage.

As long as we are aware that we visit an exhibition to see what this particular museum considers important to display, as long as we are ready to critically comprehend why it is important, and moreover for what reason it is considered important, “history”, as a scholarly discipline, which claims to be indifferent towards the political uses of its field (if that claim is ever relevant), is left undisturbed. Because we come to a museum to consume heritage – that is, those selected facets of history that the curators want us to recognize as heritage.

The problem here is that when we pick up a historical book, or start a documentary, or visit a historical museum, we are seldom conscious whether we come for the history or for the myth. We are surrounded by stories that we naturally perceive as histories, and we usually engage with objects of heritage as if they were unmediated historical artifacts. Lowenthal far from dramatizing the possible danger of deviating from criteria of truth and plausibility in our everyday lives, instead chooses to soothe the pin pricks of deception by noting that “in the public view, plausibility is as good as truth, and historians are worthy of their heritage hire.”viii

The images and the myths from Russia and Sweden

When it comes to the history of Russian-Swedish relations it can be said that within the public consciousness of Sweden, the image of Russia operates as an “inherited enemy”: a wild, destructive, and violent suppressor, even though many of the wars between the countries were driven by mutual interest in the same lands and by the irresistible desire to control and colonize the same territories. These constituted the typical motivations for the hundreds of years of confrontation, not burdened with the complex ideological motifs of the kind that would later adorn the Bolsheviks’ ambitions for World Revolution. Yet it transpired that the cessation of the centuries-old fight was not advantageous to Sweden and the inherited loss was remedied by constructing an image of Russia as a violent monster. Russia, on the other hand, had conducted numerous military campaigns subsequently, many of which were victorious, and thus the memory of Swedes as a main military adversary, one which had defeated Russian army countless times, gradually vanished, leaving no demonized image of the Swedes in Russian folklore.

In a literary guidebook by the journalist and translator Stefan Lindgren Leningrad – på andra stranden, ix published just before the dissolution of the USSR and monthsbefore the city voted to revert to its pre-revolutionary name,x a chapter is devoted to the Swedish heritage in Leningrad. The author meets a local, Aleksandr Jemeljanovitch Koltsov, introduced as a young specialist in Scandinavian studies, to exchange amusing stereotypes and myths on each other’s peoples and to explore the sites in St. Petersburg that were connected to Swedes who once lived there.

Aleksandr Jemeljanovitch revealed that Shved (Swede) was a nick-name for a small cockroach (against Prusak, a Prussian, used for a large species) and Shvedka (a Swedish woman) for a yellow turnip. (Parenthetically, Google translates the Russian briukva, the proper name of the root-crop in Russian, into English “swede”; hence the ‘international’ name does not originate from any specific attitude of Russians towards Swedish women but is a derogative from the Swedish turnip, as named in English). Aleksandr Jemeljanovitch also cites a saying that is still in use among Russians: “as a Swede at Poltava” [kak schved pod Poltavoj],xi which means to find oneself in circumstances of a complete rout.xii

Pierre-Denis Martin. The Battle of Poltava, 1726.

Stefan responded with a greater diversity of epithets that Swedes bestowed on Russians. Referring to the New Swedish Dictionary he notes that the synonyms to the word rysk (Russian) include “booze crazy or mad”: (spritt) tokig eller galen; “crack-brained”: förryckt; “being out of one’s mind”: från sina sinnen; “wild”: vild; “unruly”: oregerlig; “unbridled”: tygellös. He added that the expression “to live like a Russian” (att leva som en ryss) meant to be alarmed, to shout, and to rage: larma, skrika, rasa.xiii

The collective memory of continuous war conflicts were transformed through displacement onto images of peoples and situations on both sides; what resulted was the formation of a linguistic heritage that exhausted its original meaning and in most cases its connections to the specific historical events by which it was inspired. In Swedish collective memory the myth of the ugly Russians replaced the story of their victories. Oblivion, a healing practice of heritage, served here as a remedy for a painful history.

The history of connections between Sweden and Russia did not end with the cessation of their conflict. Rather, it formed a heritage of a different, one can say, ‘positive’ kind, and which is still largely overlooked by both Swedes and Russians alike. Both nations continued fostering their shared history throughout the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth centuries within a new space of St. Petersburg. This multilayered and complex urban heritage was formed on the lands that were reclaimed from Sweden in the fierce battles of the “Great Northern War”, so as to exercise control over the lands surrounding the mouth of the Neva river by the outlays to the Finnish Gulf of the Baltic Sea, within which the main military and trade routes of Europe were concentrated. These territories were subject to a long history of military conflicts, passing from Russian hands into the hands of the Swedish monarchy and vice versa. Doused with blood and the scars of war, these areas remain rich with material artifacts of Russian, Swedish, and Finnish presence, of their cohabitation and confrontation.

One could claim that the presence of a Swedish diaspora in the city their enemy established on their former lands lacked the legacy necessary for any heritage to be acknowledged and celebrated. Yet, by the middle of the nineteenth century, when Swedes in St. Petersburg started to play a significant role, sufficient time had elapsed for a safe distance to be installed between the present and the disturbing past, while enough ignorance of events had been fostered to clear the memories and to heritagize the shared history of the two states. As Lowenthal notes, “ignorance, like distance, protects heritage from scrutiny,”xiv and “it sets myth above truth.”xv Both states produced their myths and fabricated their heritages, hence they were ready to turn the page.

A myth of St. Petersburg

For the Russian myth, and personally for Peter the Great, this page began with the foundation of the new city as the site of and the monument to the victory over the Swedish Empire; “to spite the arrogant neighbor”, to put it in the words of the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, who gave this myth a poetic form in his masterpiece “The Bronze Horseman,” bringing the founding myth of St. Petersburg to the masses as a valuable and unquestionable heritage.xvi The myth of the origins of St. Petersburg, a city that was established on the empty marshy soils as an act of Peter’s strong will, a that in turn represented the will of all Russians as well as representing the beginning of a new country and a new history, has since become a celebrated part of Russia’s national heritage. How much this myth and this heritage approximates historical truth was not in question for the legacy of the new Russia.

Alexandre Benois. Peter the Great Meditating the Idea of Building St. Petersburg at the Shore of the Baltic Sea, 1916.

The glorification and mythologization of the history that preceded the foundation of St. Petersburg, converted it into the legitimate heritage of the city and thereby preserving the cause as a legacy of the new state. The defeated Swedish Empire was never represented as a weak enemy; it was never humiliated once integrated into the heritage of Russia. The strong Emperor defeated the equally formidable enemy, and this was to be visualized within the new capital’s urban space: the harsh struggle between two warring nations would rest at the city’s very foundations. The monuments to the victories in the Great Northern War, especially those established after Peter I’s death, allegorized the eternal struggle between good and evil, such as with the Golden Samson in Peter’s Summer Residence in Peterhoff as well as the Rostral Columns on Vasilievsky Island in central St. Petersburg.

Fountain Samson in Peterhoff. Photo by Irina Seits, 2009.

Benjamin Patersen. View tp the Spit of the Vasilijevksy Island and the Stock Exchange, 1807. From the Hermitage museum collection.

Peter I had an idea to commemorate the main victory of Russia over Sweden in the Poltava Battle of 1709 by way of an allegorical sculptural scene depicting Hercules defeat of the Lernaean Hydra, where Hercules would symbolize Russia and the Hydra representing Sweden. However, he died before his plan was implemented. When the time came to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the battle in 1734, Empress Anna Ioannovna returned to the project, though now Hercules was substituted with an image of Samson tearing apart a jaw of a lion. The allegory employed the fact that the Battle of Poltava took place on July 8, which is celebrated as the day of St. Sampson the Hospitable by the Russian Orthodox Church, while the lion was a state symbol of Sweden.

Even if nothing except their names unites Samson, an ancient hero of incredible strength, and a Christian saint, and moreover despite the fact that Samson was depicted with a short haircut so that he could more closely resemble Hercules, the sculpture became the most popular and renowned symbol of the victories of the Russian army in the Great Northern War, which enabled the foundation of the new Russian capital and hence turned the page on a new Russian history. The statue was designed by the sculptor Carlo Bartolomeo Rastrellixviiof pure gold and still occupies the central place by the entrance to Peter’s Grand Palace from the sea, which was previously used when ships entered the residence’s Grand Canal from the Gulf of Finland. The composition was designed to be the centerpiece of the fountain ensemble of the Peterhoff’s Grand Cascade, with the height of a naturally powered fountain jet reaching up to twenty-one meters.

Samson symbolized the victory over the mighty enemy, and, by way of the use of golden light refracted by the sun in the jets of crystal water, the sculpture emphasized the strategic importance of the war’s location. It represented the glorious future of a renewed country: a paradise for its friends and an eternal threat to its enemies.

The Rostral Columns at Vasilievsky Island in central St. Petersburg, which served as light towers leading ships to the port, is another symbol of the ultimate victory over the formidable Swedish navy by the young Russian fleet built by the skillful hands of the tsar (Fig.6). The columns strike the Swedish boats in a moment marking their final defeat, lighting the lights in the new window to the West. Today fires are lit on top of Rostral Columns – now among the most recognizable symbols of St. Petersburg – during state and city celebrations, or following extraordinary events.

Rostral Column in St. Petersburg.

Photo by Lana Svetlitskaya, 2021.

Winning the heritage

The struggle between Sweden and Russia sets the ground for the narrative of St. Petersburg’s origin, making Sweden one of the leading characters of this narrative and part of Russian national heritage. Events that happened on these lands three hundred years ago, and that involved both Russia and Sweden, are commemorated by these monuments in the urban space of St. Petersburg, not only to symbolize victory over these lands, but to remind us about who controls the myth of those events and who is in possession of the appropriated and domesticated past, demonstrating how a shared history becomes the winner’s own heritage.

Unlike military victories, military losses are usually not the objects of commemoration. Yet the architectural monuments of past military affairs still exist in public urban spaces, remaining as active agents and viewed as the heritage of the past. Their symbolic role, and the message they transfer to the contemporary city space, shifts and changes over time and in accordance with newly established political and cultural agenda; as Lowenthal notes, “heritage clarifies pasts so as to infuse them with present purposes.”xviii

The foundation myth of St. Petersburg is well protected, maintained, and administered. It is itself a heritage. Even though it is distinguished from historical truth, it is nonetheless valuable on its own account; to cite Lowenthal again, “heritage and history are closely linked but they serve quite different purposes.”xix The local contemporary purpose of these sites of heritage is to glorify the past and to introduce it as the beginning of a glorious present, to establish a time that bridges between then and now, to provide material evidence to the continuity or inherited legacy of present affairs. The specific role of Sweden in this heritage has diminished by now to its symbolic role of an abstract strong military adversary, to a collective image of an enemy of the State with no direct connection to the modern image of Sweden in Russia.

Amusing the past for the purposes of the present

Thanks to another of Pushkin’s poem “Poltava”, written in 1828, which turned the historical events of the Great Northern War into a celebrated example of national heritage, some of its lines became famous sayings still used in Russia today, but not with respect to particular Swedish nationals but regarding situations in everyday life. In addition to the ‘Swedes at Poltava’ saying, which is folkloric, the famous lines from the Pushkin’s poem, “Hurrah! we break; the Swedes are bending” [Ura! Mi lomim, gnutsya shvedi] is often used in anticipating victory, becoming especially relevant during ice-hockey battles between two sporting rivals.

In April 2019, during a public session at the Arctic Forum in St. Petersburg, the Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven and Russian President Vladimir Putin engaged in what the Russian Media called a ‘poetry duel’ by exchanging citations from these two poems by Pushkin: The Bronze Horseman and Poltava, both responsible for contextualizing the Russian-Swedish common past, and placing both Russia and Sweden in a shared heritage. The cited lines required understanding the multiple meanings stored within them, as well as knowing the events that produced the context, a fact that was only fully intelligible to those who belonged to this heritage and who, in spite of profound ideological differences, shared it.xx

Alexandre Benois. Frontispis to a publication cover of the Alexander Pushkin's Poem The Bronze Horseman', 1905.

Löfven began his speech at the Forum by speaking of the close historical ties between Sweden and Russia and, given the occasion, expressed a desire to “borrow from the great Pushkin,” citing the introduction to the Bronze Horseman: “From here the Swede is ill-protected: /A city on this site, to thwart / His purposes, shall be erected.” The citation was spoken in English and met by the international audience with an applause and approving laugh.

Stefan Löfven used here the translation proposed by John Dewey. Putin, who understands English, repeated the original verses in Russian, which, in a literal translation give a more precise ‘characterization’ of the Swedes, and a better outline of the ‘purpose’ of the city’s foundation: “From here we will threaten a Swede. / Here the city will be laid / To spite the arrogant neighbor.”xxi Following that Putin, in his turn, responded to his Swedish political counterpart with a line from another poem, “Poltava”: “Hurrah! we break; the Swedes are bending” [Ura! Mi lomim, gnutsya shvedi], admitting right away that these words are usually recalled during titanic sport battles, but, unfortunately, not as often as he would wish when it comes to football competitions between Swedish and Russian national teams.

This episode demonstrates that, although appropriated and directed by the “winner”, shared heritage is not entirely in the hands of the possessor, but rather it operates on its own account. Such moments, as Lowenthal puts it, help us recall “that no heritage is wholly homegrown.”xxii

The mutual recognition of the shared Swedish-Russian heritage exists on the highest official levels, while urban sites referring to St. Petersburg’s beginnings are actively exploited by the industry of heritage tourism.

And yet there is a whole corpus of Swedish urban heritage to be found in the city that is still ‘ill-protected.’ After the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, international heritage in Russia was deprived not only of its legacy and legitimacy but, more, its right to remain in the city as heritage, precisely because it revealed and manifested its international background, upon which the Soviet regime declared war. The second part of this essay is devoted to the destiny of some Swedish heritage in St. Petersburg after the Revolution, mostly those heritage sites formed in the city by the Nobel family.

The undesired treasures of the unforgotten past

Besides the vulnerable and neglected heritage of the international industries, which settled in St. Petersburg from the very beginning, there is today a new conflict raging between the contemporary oligarchy of the Russian Gazprom company, on the one side, and the defenders of city heritage, on the other; a line of antagonism presently unfolding around the newly discovered treasures of the past shared by Sweden and Russia at the crossing of the Okhta and the Neva rivers in central St. Petersburg. Since the beginning of the 2000s, the territory at the confluence of the Neva and the Okhta has attracted the Russian gas and oil giant Gazprom as a dream spot for their business and administrative quarters. A skyscraper was planned to be built on the renowned archeological site where the Swedish fortress of Nyenschantz (in Swedish - Nyenskans; in Finnish – Nevanlinna) was located in 1611, and next to which the town of Nyen grew fast into a large trade and industrial center of the Swedish Ingria, attracting Germans, Russians, Finns, and others to join its international community of nearly two and a half thousand people (Fig.8).

Model of the Nyenschantz Fortress and the Nyen city from the Nyenschantz Museum in St. Petersburg. Photo by Evgeny Gerashchenko, 2007.

The fortress was conquered and destroyed by Peter I in 1702, which allowed him to exercise control over these lands and regain the surrounding area of the Baltic Sea. Most of the residents left Nyen and fled to Sweden or scattered around neighboring regions. Some Swedes though, if they were not taken as war prisoners and forced to work on the city’s construction, accepted the Russian Tsar’s invitation to contribute to the development of the city, becoming its first local residents. Hence the Swedish community in St. Petersburg was contemporary with the birth of the city itself.

The Nyenschantz Fortress was believed to be razed to the ground in the Great Northern War, while the town of Nyen was destroyed for the use of construction materials in the new Russian capital. Since not much seemed to be left on the site, in the middle of the 2000s the city administration approved Gazprom’s ambitious project to construct a tower of almost four hundred-meters tall. In 2006 the whole city raised in protest, in defense of the whole city whose iconic skyline, protected by UNESCO, would have been hopelessly lost if a monstrous phallic structure had been erected on this historical site. The anxiety and outrage among the locals and global admirers of St. Petersburg intensified once in 2007 the archeological excavations on the site discovered that the fortress of Nyenschantz was preserved in much better condition than previously thought. The city won the fight for the site and the tower was moved to the Lakhta area, not far from St. Petersburg, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland, where the project was successfully realized. Yet, the spot that had been defended seemed too attractive for Gazprom to give up, and so during the beginning of the next decade, discussions about the appropriation of this historically symbolic site began once more.

This time the debate unfolded around Gazprom’s idea to build an office center on this territory while promising to preserve the historic site and the remnants of the fortress. During new excavations, which started as part of a legally required dig led by the St. Petersburg archeologist Petr Sorokin, some new unexpected things were discovered under the Okhta district soil, concealed for the past three centuries. The media referred to the new findings as the ‘Russian Troy.’ During the excavations, not only were some random fragments of the Nyenschantz fortress discovered, but large parts of bastions, ditches, and parts of the buildings were found and were well-preserved. In addition, the lower levels of the Nyen’s living houses and shops were excavated along with the Necropolis of the time. Further archeological digs yielded even more finds. Beneath the destroyed fortress the remains of the original wood-earthen Nyenschantz of the 1611 were discovered, and further down, to the amazement of archeologists, there were the remnants of the ancient Swedish Landskrona Fortress, which had been built in the 1300s, on the territory that at that time was controlled by Novgorodians.

Archeological investigations into Landskrona did not exhaust the soil of Cape Okhta; further treasures were revealed. Under Landskrona, Sorokin’s team discovered an even older Russian settlement and, a Neolithic settlement dating back to 3-5000 B.C. was found, excellently preserved. Archeologists discovered wooden constructions and decks along with a large amount of fishing tackle and various other devices.xxiii

Instead of the news breaking in the media with sensational and celebratory headlines, these archaeological finds turned into disturbing obstacles for the realization of the new Gazprom’s project. Gazprom had not considered the need for such a large conservation area for the purpose of an archeological park, which both the historians and conservationists now found to be the only acceptable solution. Even though the idea of an archeological reserve and a museum was supported by President Putin, Gazprom has far from given up its plans to build a business center in the area. Instead of the media publicizing the findings, there was an information vacuum: very few locals, not forgetting people living further afield, have even heard about the extraordinary archaeological finds, or about Gazprom’s plans to construct a business center in the area.

Several activist groups, scholars, and local deputies have been trying to organize mass support for the archeological site in the city. In November 2020 an article on the issue even appeared in the Swedish Newspaper Dagens Nyheter;xxiv some interviews were published in online media, and a website set up by a group is regularly updated. However, to date no state media sources in Russia have given the case a fair hearing. Anna Aparneva, one of the young activists and a fifteen-year old journalist concerned with the fate of the site, reflects on the reasons for the silence around the Nyenschantz:

I think that 9 out of 10 people would reply “no” to a question: “Have you heard about the problem of the Okhta Cape?” I suppose that the reason is not only in poor coverage of the problem by the media, but also in that these objects, which require preservation, are invisible. If a person was passing by a historic building that was in a state of a ruin, he could immediately conclude that this building required reconstruction. But a person who is passing by Cape Okhta only sees a fence and does not even have a clue about what hides behind it.xxv

The lack of heritage visibility is one of the most crucial problems surrounding the preservation of such sites. And yet, some other places of heritage in St. Petersburg –such as buildings and artefacts associated with the Nobel family– are not so closed off and geographically hidden away. This is something into which I will delve further in the second part of this essay. And yet, despite their prominence in the city, little concern is raised among its citizens about their poor physical condition and the need for restoration. Even though these sites occupy large areas in the historical center of St. Petersburg, and, as is the case with the Ludvig Nobel’s former luxury mansion, designed by famous architects, even overlook the Neva River, thereby contributing to the city’s water front, such examples of heritage still remain invisible to both locals and city administrators.

The Nobel Mansion on Pirogovskaya Embankment in St. Petersburg. Photo by Irina Seits, 2016.

Ludvig Nobel (Russian Diesel Plant) in St. Petersburg. Photo by Irina Seits, 2021.

The Soviet policies of heritagization and the practices of oblivion

The Soviet state ideology, dominant in Russia for a large part of the twentieth century, practiced oblivion towards large parts of St. Petersburg’s urban heritage, administering and institutionalizing its hierarchization. This, it seems, prepared the conditions for what the Russian film director Sergei Eisenstein called the ‘trained ignorance’ in his notes to an unrealized project “The Glass House”, dating back to late 1926. There the people live in a transparent house entirely made of glass, but “acting through the walls and floors, [they] do not see each other,” because they have already learnt to look at their living space and at what surrounds them without seeing it.xxvi Originally, the project aimed at depicting a critical allegory to the highly individualized capitalistic society of Western Europe and the US, where people were disconnected and ignorant towards each other. Yet at the time Eisenstein’s notes linked the transparency of his glass house with a society predicated on totalitarian control and surveillance, and thus the project was never finished.xxvii

During its 300th birthday St. Petersburg was celebrated as a gem of the glorious past, linked once more to Imperial Russia rather than to the Soviet state, which in turn symbolically outlined the ambitions of another founder of the new Russia, Vladimir Putin. The young President, being a native of St. Petersburg, had just turned another page of Russian history, analogous to Peter I who had started writing Russian Imperial history from scratch on these lands, after divorcing with Moscow. An heir to Peter, Putin symbolically confirmed a new break with the past by returning to St. Petersburg’s landscape its lost luster and by converting it into an administrative hub for his government. In this light, ignorance surrounding parts of the heritage, which no one still knows how to address, and no one is sure to whom it should belong – as in the case with the international industrial heritage – discloses the lack of agreement existing in contemporary Russia surrounding the many episodes and periods of its recent past.

The heritage of an unclear past does not become visible on its own account. It must be rediscovered and promoted as such. The passers-by of the sites of neglected and dilapidated heritage should be taught to see them as valuable heritage at risk of disappearing; they need to know what they are passing by and why they should care about restoring the pity ruins of an unclear value. The value of what is being institutionalized as heritage requires its propagation, since heritage is always a product of a history both mediated and propagated.

In a recent interview given to the local media portal Gorod 812,xxviii Adrian Selin, Professor of History at the Higher School of Economics in St. Petersburg, a specialist in the history of Swedish-Russian relations of the 17th century, raised several questions surrounding the value of this heritage and the various problems associated with its existence in contemporary St. Petersburg: should the city conserve all historic objects and sacrifice development and modernization? What is the principal value of original artefacts, who and how should decide on whether and in which forms it should be shared with the public? To whom does this heritage belongs and how accessible should it be? What gives legacy and value to the city landscape? Questions such as these are not unique to St. Petersburg, but apply to all sites of historic heritage. The case, for example, of the treasures found in Cape Okhta is very interesting in this regard, and though it stands outside the scope of this essay, I hope to be able to return to it soon.

The Swedish heritage and the Soviet state

After the Revolution of 1917 the Swedish urban heritage in St. Petersburg – the houses the Swedes built for their homes, the factories they established, the Swedish Church that concentrated the life of the city’s Swedish community (Fig.11), the schools, the numerous shops and studios, etc. - all were erased from the city’s urban memory, deprived of their legacy and disconnected from the Swedes and even from their association with the Swedish citizens of St. Petersburg.

Swedish Church of St. Catherine in St. Petersburg (Sankta Katarina kyrka), photo of the 1900s

Certainly, the Swedish community in St. Petersburg was no exception. The much larger German, British, Finnish, and French diasporas shared a similar destiny with other international communities and native Russians from the wrong class background. Their systematic removal from their spaces, the exile, and deprivation of rights not only with respect to confiscated property and life routines, but surrounding the very memory of these quotidian practices were organized into new state policies, which, as I argue here, employed some techniques of heritagization regarding what was not to be protected under new laws surrounding heritage preservation.

Lowenthal stresses that heritage is a doctrine of almost a religious nature: one should possess a legacy of belonging to and sharing the whole, since “to share a legacy is to belong to a family, a community, a race, a nation,” while “those deprived of a legacy are rootless and bereaved.”xxix

The policy of the new Bolshevik state towards city property targeted those who were declared the enemies of the state, a category under which most foreigners fell for one or another reason. The aim was to disconnect these remaining material objects from their origins and backgrounds, cutting them off from their roots. The goal was a complete oblivion of the past, a break with the whole of the former experience and its impoverishment, in Walter Benjamin’s sense.xxx

Yet, the practice of oblivion, as discussed earlier, might be not as easy and straightforward to realize when it comes to the urban space, which is built up of strong ties and direct references to particular things that must be forgotten. To achieve a break with history and former collective human experiences, the Bolsheviks had to develop an entirely new policy of systematic oblivion and to equip themselves with the necessary tools to put this into practice. It is not easy to forget a particular building if you encounter it on your way to work every single day, especially, if by its own design and structure it speaks to you about what you must forget; as is the case with a golden-domed Orthodox church or a former royal palace, for example.

At the apogee of the Revolution, the dense space of St. Petersburg was packed with old hostile stuff that was to be removed – either physically or ideologically from the city’s landscape. The urban space was to be cleared of all references to the old world, which was to be destroyed to its very foundations in order to empty the space for a new world to emerge, as is sung in the Internationale:

We will destroy this world of violence

Down to the foundations, and then

We will build our new world.

He who was nothing will become everything!xxxi

The Bolshevik state had put huge efforts into cleansing and purifying the old urban areas of the former Imperial cities of as many references to the defeated era as possible. As the heart of the Russian Empire, St. Petersburg was the flesh and blood of imperialism in its planning, its architecture, and its symbolic nature (Fig.12). The goal to return to the natural space, in order to prepare for new appropriations, to use Lefebvre’s terms,xxxii was nearly impossible without a complete demolition of much of its architecture; St. Petersburg was after all the child and the heir to the Russian Empire. Lefebvre claims that “(Social) space is the (social) product,”xxxiii and Bolsheviks, when destroying churches and royal palaces, cleared the space of products that resembled the relics of a defeated ideology; new ideas would supplant the old, and would arise from out of the production of new social spaces. Lefebvre criticized this flat understanding of social space, arguing for its complex nature, including both physical as well as temporal, social, and psychological dimensions: […] a social space is constituted neither by a collection of things or an aggregate of (sensory) data, nor by a void packed like a parcel with various contents, and that it is irreducible to a ‘form’ imposed upon phenomena, upon things, upon physical materiality.xxxiv

Swedish Evangelical Lutheran Church of St. Catherine in St. Petersburg (Sankta Katarina kyrka), photo by Yoshi Canopus, 2009.

Yet, such a flat perception of space was characteristic of the Bolsheviks. Fortunately for the city’s urban body, Bolsheviks moved the capital back to Moscow already in 1918, which saved St. Petersburg from the complete physical demolition of its urban space. Obviously, this does not mean that the city was left untouched. In her book “Petersburg, Crucible of Cultural Revolution”,xxxv Katarina Clark explains that St. Petersburg’s center managed to avoid destruction because “the locus of value was shifted from the center to the periphery.”xxxvi The coexistence of these two ideological centers was debated at length. The old Imperialistic area would soon be regarded as a museum artifact and a heritage of anthropological and historical value, rather than of cultural and ideological significance. Moreover, there was the attempt to shift the new ideological center to the outskirts of the city:

Soviet rhetoric began to insist that there were two Petersburgs, the old Petersburg, which must be destroyed completely, that is, monumental St. Petersburg as oppressive Imperial capital, and the new Petersburg as an industrial city and hothouse of the new culture. But the two were also said to have separate locations. As Shklovsky remarked at the time: “Peter(sburg) is creeping to its periphery and has become like a bagel-city (actually bublik) with a beautiful but dead centre.xxxvii

Various techniques of oblivion were applied to “forget” the inappropriate heritage and to remove it from the city’s cultural and ideological space, as well as erasing it from the people’s memories. One of these techniques was to rename urban spaces. The rich urban heritage, which had been formed in the city before the Revolution of 1917 by the Russian and international entrepreneurs, including prominent Swedish families of Nobels and Ericssons, were sent into an internal exile. In the second part of my essay I will focus mostly on the Nobel family and the heritage they left in Petrograd after fleeing the country in order to escape from the Revolution. Their story is overwhelmingly dramatic and yet horrifically exemplary for its time. The story of the Nobels in Russia is part of Russia’s and Sweden’s common heritage, which throughout most of the twentieth century had been muted, suppressed, and deprived of its legitimacy, by both Sweden and Russia. Even today, thirty years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, which ended the proclamations of oblivion, the memory of this heritage has not been restored to the extent that remains commensurate with its historical value, in spite of the fact that a huge part of this heritage has survived nearly an entire century of neglect.

Renaming as a constructive tool for new heritage

David Lowenthal stresses that heritage, unlike history that deals with events of the past, has to do with both a faith in the past and with its celebration. Hence questions surrounding who gets to control the past, who gets to interpret and adjust the past to present purposes, as well as who chooses what is to be celebrated, are all political questions. Any revolution or radical change in political regime or state ideology tends to systematically revise, if not erase, the previously dominant culture and reject that culture’s heritage to clear the space for the establishment of a new legacy. History, though, is not so easy to cancel and reject, hence the continuous practices of its constant revision and re-writing in order to adapt it to current purposes in all parts of the world and at all times. Material heritage, on the contrary, when seen as evidence of history, can be physically destroyed, with the demolition of outdated and ‘illegitimate’ monuments serving as a paradigmatic example.

Architectural heritage is, however, more difficult and costly to demolish and replace with the right buildings, both ideologically and politically speaking. The Bolshevik state had to limit its intentions to materialize the verses of the Internationale and to destroy the world of violence to the foundations by demolishing countless churches – the objects of the rejected heritage, least adaptive to the new atheistic ideology. Dozens of Russian Orthodox churches were destroyed in St. Petersburg, joining the statistics of tens of thousands that were demolished during the first decades of Soviet power around the country. Yet, it should be noted that the whirlwind of destruction bypassed most of the main non-Orthodox cathedrals in the city. For instance, the building of the Swedish church located in the heart of the historical center of St. Petersburg, close to the Nevsky prospect, escaped demolition, and in 1936 was converted into a gym. Most of the cathedrals in the city not pulled down were reconstructed as libraries, sport facilities, warehouses, factories, and workers’ clubs. Hence, cathedrals, as part of the ideologically hostile heritage of the Imperial past, were either adapted for new purposes or, in cases where their architectural symbolism exposed too many details about the defeated era, were physically removed from the newly appropriated urban landscape.

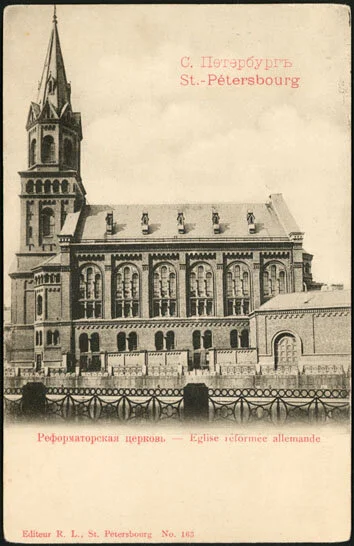

German Reformed Church in St. Petersburg. A postcard from the 1900s.

Postal Workers House of Culture (former German reformed Church) in Saint Petersburg after reconstruction, photo by Alex Fedorov, 2013.

When it came to the hostile heritage of other kinds – for instance, former royal and noble palaces and factories of capitalists and exploiters – a different practice of oblivion was adopted. Under the slogan Land – To Peasants! Factories – To Workers! Power – To the People! the policy of nationalization transferred all private property to the hands of the Bolsheviks. Palaces, mansions, state buildings, theatres, and factories now belonged to the state and were appropriated and repurposed for the new ideology. Noble mansions were turned into communal apartments, palaces to the headquarters of new institutions, and so on.

The enormous industrial heritage of St. Petersburg-Petrograd, which by the beginning of World War I developed into one of the world’s leading technological and industrial centers, was left behind by its owners fleeing the revolutionary city. Many of the factories during the first years after the Revolution either grossly reduced their production or ceased indefinitely, while others were either neglected or preserved. When the Civil War ended and the Soviet state returned to its industrial heritage, the resurrected plants and factories were redescribed as the products and achievements of the new Soviet regime. The main strategy chosen by the state for this purpose was the strategy of renaming. This meant much more than simply replacing one signboard with another. On the one side, the renaming of each inherited industrial object erased records of their origins and disturbed memories of their history; on the other, the new names introduced these objects as the products of the new Soviet state, and to future generations – as the celebrated heritage of the regime.

The strategy of renaming urban spaces and their architectural objects was widely used by the young Soviet state after 1917. It was not an invention of the Bolsheviks, but rather an old tradition used around the world to commemorate the appropriation of new lands. At the same time Bolsheviks universalized renaming into an effective method of introducing the heritage of the defeated past as an achievement of their successful and victorious present. In the second part of this essay I focus on the destiny of the Swedish industrial heritage in St. Petersburg, but it should be noted that this method was applied all over the country and to various types of former imperial Russian heritage.

St. Petersburg, the first victim of renaming

St. Petersburg itself became the first victim of the practice of renaming. It had lost its original name even before the act of renaming everything became a generalized practice. The aim of renaming was to erase the traces of the past and to divorce people from their everyday experiences.

The original name of St. Petersburg refers to its regal background as the capital of the Russian Empire. After the start of the WWI in 1914, the city’s name was translated from the German Sankt-Peterburg to the Russian Petrograd. The translation preserved an idea that it was the city of Peter, yet it accepted a symbolic loss of the ‘saint’ prefix, hence shifting accent from Saint Apostle Peter, in whose honor the city was originally named, to its founder Peter the Great – the victorious military leader and the strong-handed politician (Fig.15). The name of Petrograd marked a specific decade of the Russian history from the break of the WWI to the success of the Bolshevik Revolution and formation of the Soviet Union (1914-1924).

The Bronze Horseman (monument to Peter the Great). Photo by Lana Svetlitskaya, 2021.

After the death of Lenin in 1924 Petrograd was re-named as Leningrad, an act as revolutionary as it was symbolic. The name of Leningrad commemorates the real man, the leader of the Revolution and the founder of the new state (Fig.16). The city’s name labels its urban landscape as a memorial site both of Lenin and the Bolshevik Revolution, which happened on its very soil. From now on the city is strongly associated with Lenin, who ushered in a new history, and not to Peter who did the same thing two hundred years before. On the one hand, this is a triumphal act over a rejected ideology, but on the other, the name of Leningrad continues the tradition of calling the city “the grad of Lenin,” which means the city of a concrete man – be it a patron saint of the urban space, its political father, or a revolutionary successor. Leningrad declares the beginning of a new history and an irrevocable break with the old. Whatever heritage remains on its landscape is not Leningrad’s heritage anymore, since Leningrad divorced from St. Petersburg-Petrograd to produce a heritage of its own. Here the act of renaming transforms into an innovative political technology of appropriation, Sovietization, and ideological colonization of the Empire’s conquered space. This technology is further developed and refined through re-naming internal urban heritage, its districts, streets, and architectural sites, giving them names of the heroes of the Bolshevik Revolution.

Monument to Vladimir Lenin at Finlandsky Railway Station, a Soviet Stamp.

An ideological break with the past, occurring with the very renaming of Petrograd into Leningrad was crucial; the new name eliminated any connection of the city to its pre-revolutionary past. In a twist of the myth of its origin, the city was stripped of its heritage, disencumbered of its original background. Leningrad was given a clear indication of its new identity and granted a new faith in its past and its future. The city’s landscape hence became a setting, in the words of Lisa A. Kirschenbaum, “for another myth of origins as ‘Red Petrograd,’ the cradle of revolution,”xxxviii a metaphor that was widely used throughout the city’s Soviet period.

After a referendum in 1991, the original name of St. Petersburg was given back to the city, indicating the restoration of the legitimacy of imperialistic heritage, and outlining the return to capitalistic ideology, setting also the ground for the future neo-imperialistic ambitions of the state. Shortly after, the city administration returned thirty-five historical place names to the streets that carried a reference to the Soviet regime in what Kirschenbaum calls “the most extensive local round of name changing since 1923.”xxxix

Every tread of land refers to its possessor. To name land is the first and basic means of appropriating space. Each pioneer, who reaches a new unknown land, as well as each conqueror, first bestows upon it a name in order to lay claim over it. Natural space acquires its status as man’s property through the name. Once land is named, it is no longer a random site of nature; it is transformed into a social object and acquires shape through its newly assigned borders.

A change in the town’s name, from the perspectives of both history and ideology, shifts the accent with respect to the heritage that this urban space aims to resemble. The very history of transformations in the city’s name is representative of the city’s personal history and what was deemed appropriate to include as its valuable heritage. This includes also the city’s existing name, which, in its own way, reflects a prevailing ideology.

The circle looks as if it is closed for the moment, and yet even the most recent history of St. Petersburg-Petrograd-Leningrad-St. Petersburg reveals its cyclical nature. Historically, these lands were subjected to endless fights for the right of their re-appropriation. The moments of victory over these lands were commemorated by an instant naming of the conquered land, which fixed the legitimacy of its new owner, and which was further confirmed by the construction of a new fortress to protect this new name.

In the fourteenth century it was, for instance, Landskrona – The Land’s Crown –that commemorated the coronation. It thereby served as a declaration that these lands belonged to the Swedish crown, even though the fortress was secretly built on the lands, which, at that time, were owned by the Russians. Nyenskans – The New Fortress – restored the connection with Landskrona over the centuries of the Novgorodian rule, establishing faith in the continuity of heritage and the legacy of Sweden as the true heir to these lands. The foundation of the Peter and Paul Fortress in 1703, although it was built in Swedish forms, marked the beginning of a new history in these lands, giving the first heartbeat to St. Petersburg.

View to the heart of the city - Peter & Paul Fortress. Photo by Grigory Brazhnik, 2020.

I would like to thank David Payne for his help in preparing this article as well as my friends and colleagues Grigory Brazhnik, Natela Gamolina, Oleksandr Polianichev, and Lana Svetlitskaya for sharing images from their personal archives.

Irina Seits is a researcher at Södertörn University (Sweden) with affiliation to the Centre for Baltic and East European Studies (CBEES). She received her MA in Art History from St. Petersburg State University and the European University at St. Petersburg. Her interests include the architectural and urban theory of modernism, the cultural heritage preservation, and the aesthetics of the everyday.

i David Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998).

ii Ibid, X.

iii Ibid, 156.

iv Ibid.

v Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Europe, Europe: Forays into a Continent (New York: Pantheon,1990).

vi Ibid, 159.

vii Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History, 159-160.

viii Ibid, 167.

ix Stefan Lindgren, Leningrad – på andra stranden (Stockholm: Ordfront, 1990).

x Leningrad was given its original name of Saint-Petersburg as a result of the referendum that took place in 1991.

xi The Battle of Poltava (July 8, 1709) was a decisive victory of Russian Tsar Peter I over Swedish Empire in the Northern War, even though the Peace Treaty of Nystad that ended the war was signed only in 1721.

xii Lindgren, Leningrad – på andra stranden, 78-179.

xiii Ibid. The contemporary online Swedish dictionaries give similar synonyms to the word “rysk.”

xiv Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History, 135.

xv Ibid, 130.

xvi The poem was written in 1833, first published in 1837.

xvii In 1802 it was rebuilt by sculptor M. Kozlovsky and in 1947 restored by sculptors V. Simonov and N. Mikhailov.

xviii Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History, xv.

xix Ibid, 104.

xx https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2608389.html

For the fragment of the session with the ‘duel’ look, for instance here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JaFkgtlRW_8

xxi The Swedish version also gives a more literal translation: Han tänkte så: / Just härifrån skall svensken hotas, / Här skall vi bygga upp en stad / Som trotsar denne sturske granne

xxii Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History, 247.

xxiii For more details on discovery see the lecture by Vsevolod Pezhemskiy (in Russian): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ejNCxhuLGVw

and a collective article by the youth journalists of the Ligovo Centre: Let’s Save the Okhta Cape: An Archeological Monument at the Okhta Mouth River: https://bashne.net/?p=6284

xxiv ”Svenska fornlämningar i Sankt Petersburg hotade,” Dagens Nyheter, 2020-11-18: https://www.dn.se/varlden/svenska-fornlamningar-i-sankt-petersburg-hotade

xxv Ann Aparneva, “What Does the Motherland Starts With? We Know. And St. Petersburg?,” Alfa Praktika, 1 (06), February (2021): bashne.net

xxvi Naum Kleiman, “The Glass House of Eisenstein,” Iskusstvo Kino [The Art of the Cinema], Vol.3 (1979): 96

xxvii For more on the Eisenstein’s project see Irina Seits, (). “Revolutionised Through Glass: Russian Modernism in the Age of the Crystal Palace,” Modernity: Frontiers and Revolutions (London: CRC Press, 2019), 51-56.

xxviii “There is no strategic breakthrough in building another glass construction in the city center,” interview with Adrian Selin, in GOROD 812, 07.12.2020. https://gorod-812.ru/adrian-selin-net-nikakogo-strategicheskogo-proryva/?fbclid=IwAR0AMn2JPDYF3MJ-oVgwy37gB1ZwQhBzePSvx9at1Iqe-OZ1jmQlGTK_B20

xxix Lowenthal, The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History, 2.

xxx See Walter Benjamin, “Experience and Poverty.” in Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, Vol. 2. 1927-1940. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999), 731-736.

xxxi This is a literal translation of the Russian adaptation of the Internationale lyrics by Arkady Kots (1902) Full text available here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Internationale. Accessed on: 28.02.2021

xxxii The theory of social space and its production was introduced and summarized by Henri Lefebvre in The Production of Space (1974), trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1991). Lefebvre introduced the use of the term “social production of space” and “spatialisation” as one of the modes of space production from a natural “absolute” space to the complex social space – through the process of appropriation. Thus, he argues that the social space is a social product; each society appropriates in its own way natural absolute space, transforming it into the social space. What results is the complex constitution of the produced social space.

xxxiii Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 26.

xxxiv Ibid, 27.

xxxv Katarina Clark, Petersburg, Crucible of Cultural Revolution (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995).

xxxvi Ibid, 265.

xxxvii Ibid.

xxxviii Lisa A. Kirschenbaum, “Historical buildings and street names in Leningrad-St. Petersburg,” in M. Bassin & M. K. Stockdale (eds.), Space, Place, and Power in Modern Russia: Essays in the New Spatial History (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2010), 210.

xxxix Ibid, 254.