Raving in the conference hall

Isabel Löfgren

My return to Transmediale after a "virtual" hiatus during the pandemic brought back memories of what seemed like a distant past. As a veteran Transmediale goer for more than a decade, I felt like going to a club where art, technology, politics, and theory blend together and cross-pollinate almost seamlessly. Not exactly a university conference, but it has university people in it, not exactly an art show, though many artists participate, and not exactly a subculture, but many ‘tribes’ attend it. One of those places that becomes a site of productive trouble for those seeking a forum for addressing issues that would otherwise be considered too geeky and not art-worldly enough elsewhere, but still being alternative enough to be able to both belong and stand outside these worlds. For someone between these worlds, Transmediale is a pilgrimage – a home of sorts.

Transmediale at Akademie der Künste, 2023, photo by Silke Briel.

Psychoanalysis has taught us that “home” is not always the place of comfort – it is a source of trouble, if not outright trauma. We are always in a limbo, neither belonging anywhere nor having found our final resting place. Perhaps in-betweenness, as I later learned by listening to McKenzie Wark’s talk and reading her book Raving (2023) isn’t such a bad place after all—it is both productive and an aesthetic. I will get back to this later.

Going to a physical conference again after the COVID-19 pandemic is a most welcome experience after the “Zoom sadness” of the last three years. But being freed from social distancing does not mean a return to an analogue existence. On the contrary, while Transmediale has always paid close attention to new technologies in their events, all of this year’s events followed the new post-pandemic event protocol. I lost count of how many screens and cameras were placed for the audience in the "Blue Room" at Akademie der Künste that enabled streaming and hybrid participation, along with several sound and image technicians and their multiple screens. Not to mention that most speakers read from their laptops or their mobile phones. In the audience, using mobile phones to make image annotations and instantly posting on social media became the norm. Anyone could experience the festival remotely in real-time in I don’t know how many platforms, even diabolical Twitter. We have become more digital than ever. Point of no return? Outside the conference rooms, a loungy clubbish ambiance with colored lights and silver glitter curtains here and there, contributes to a more relaxed atmosphere than more traditional conferences held at universities, which makes Transmediale dynamics more like a cultural center.

Transmediale, 2023. Photo by Laura Fiorio.

If in 2021, the festival theme was “refusal” where potential forms of new socio-political realities were explored, after two years of the pandemic’s “great acceleration”, this notion has become obsolete. In this era of colossal technological change, smartphone devices, algorithms, and artificial intelligence have become dominant factors in the biopolitical management of our entire lives, which now appear as effects of Big Tech algorithms and planetary logistics. Now it has become clear, as Geert Lovink argues in his newly published and freely distributed manifesto Extinction Internet manifesto, that we need to understand how to ride the dynamics of disaster where “media technologies have entered the body in such a way that the body and soul can no longer be separated from the semiotic infosphere,” as he writes, inspired by Franco Bifo Berardi.[1] In 2023, the focus shifted to notions of scale and how strategies and politics of temporary withdrawal of the body from the coercive forces of Big tech—which has made claims on everyone’s subjectivities—can take form as strikes, counter-strategies, or alternative spaces. But withdrawal as a strategy of liberation from oppressive technological structures occur at multiple scales of organizing that have implications of protecting our subjectivities from being hijacked by technological apparatus that we feel unable to “opt out” from.

Most program points aimed at critically evaluating the possibilities and effectiveness of resisting multiple extractivisms—of subjectivities, labor, and data infrastructures—at planetary scales and intimate scales through artistic strategies, teaching practices, and collective organizing. Many discussions centered on technologies of extraction, largely based on colonial and neo-colonial practices, and their political, cultural, social and physical effects. From the more concrete effects of extractivism of mining in South Africa, to the exploitative cultures of labor in Amazon sorting centers, the exploitation of precarity in gig cultures, down to the extraction of our own subjectivities resulting from neoliberal imperatives that have consequences on several scales, from the planetary to the intimate spheres. When one realizes they cannot win over the system, the body then becomes the last bastion of resistance.

For example, South Korean artist Ayoung Kim used research on the algorithmic labor of food delivery workers in Seoul during the pandemic to create a speculative fiction narrative where the main character is an anti-hero gig worker in a deserted metropolis. US political scientist Charmaine Chua's analysis of Amazon's logistics—from just-in-time delivery to powering the Internet infrastructure that makes this possible—the urgency is to understand how it may still be possible to organize collectively and confront these power structures from the bottom up, or to develop productive (and not defensive) strategies of withdrawal from technological presence, extraction, and surveillance. The creative research group Planetary Portals, comprised of Casper Laing Ebbensgaard, Kathryn Yusoff, Kerry Holden, and Michel Salu, presented a lecture performance with a polyvocal reading of their archival research on diamond mining in late 19th century southern Africa to shed further light on the continual practices of extraction and its devastating consequences for local communities, as well as their dependence on a neo-colonial expansion of modernity—one based on intensified mineral extraction to supply an increasing demand for rare minerals for the coming “green” transition. The reading was complemented by Michel Salu's video depicting a maimed futuristic body wandering through a barren landscape of open mine pits, which like Kim’s and many other films in the festival was created using gaming video softwares like Unreal. These are just two of many examples of artistic and theoretical approaches presented in this year’s edition titled “a model, a map, a fiction,” which also inaugurates the new director’s Nora O. Murchú’s more practice-based approach to the event.

Ayoung Kim, Delivery Dancer’s Sphere (still cut), 2022, Single channel video, 25 min, image Gallery Hyundai.

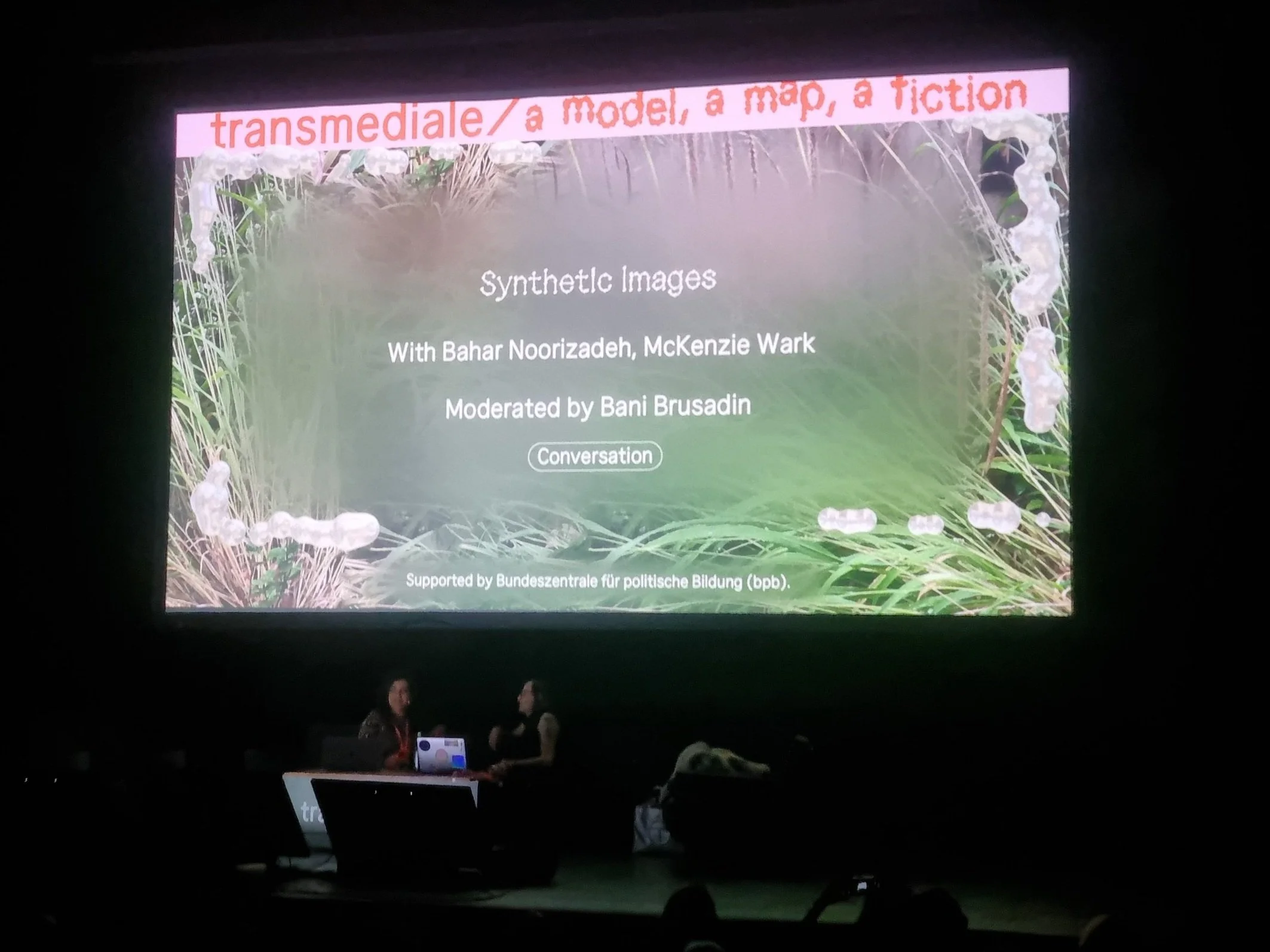

And it is precisely this notion of withdrawal of the body into other spaces which was one of the points discussed in the conversation between Iranian artist Bahar Noorizadeh and Australian media theorist McKenzie Wark. In this winding conversation held on a sofa on the stage of a huge auditorium, the artist and the theorist talked about their common interest in the aspects of labor. The first part included a screening of Noorizadeh’s film Teslaism, part of her practice which according to her website investigates the “histories of economics, cybernetic socialism, and activist strategies against the financialization of life and the living space” (her work would deserve an article on its own). The latter part of the conversation turned into a soft launch of McKenzie Wark’s upcoming book Raving (part of the Practices series, edited by Margret Grebowicz), with Noorizadeh as Wark’s interlocutor. In this rather short book, which I read only after the conversation, Wark presents the potential of the rave scene as a temporary withdrawal from the mediated self, a self that has become a site and surface for multiple extractions: the extraction of time, space, and subjectivity through various encroachments of media and image-making (and image-hostaging)—which allows the body and its subjectivity to resist being captured, even if only temporarily, by the seductive co-optations of technology. It is difficult to dance with a mobile phone, she says, and this invites one to become liberated from all media apparatuses, if only for a while, in a temporality she calls k-time, an abbreviated form of ketamine time, alluding to the drug used by many ravers to suspend reality while raving.

This doesn’t mean, however, that the club scene is completely free from technology. DJs operate with extensive databases of sounds and music to keep the rave going. In virtual k-time, she writes, “the automated production and repetition of sound signals echoes what many 21st century machines do.” As these machines play on, “the styles of both the social diagram and the aesthetic practices in these situations lace together with contemporary technics […] [and] embodies the improvisation of sound and of life within the affordances of machines.” But the fact that some clubs do not encourage photographing or other forms of image-technical intrusion can become one such “Big Tech-free” zone, to preserve subjectivities and bodies in a kind of safe space, and no less because raves are shape-shifting events held in different locations every time and not necessarily open to everyone unless you have a inside connection. Also, it safeguards another kind of extraction we normally associate with how popular culture works – style extraction or extracting a “style surplus” out of these events when made too public, harvesting dance moves, styles, looks for the benefit of the cultural and information economy elites. K-time also alludes to the notion of dissociation between temporalities and world-historical dissociations, sprung from the notion of dissociation to (gender) dysphoria in the real and metaphorical sense of a productive aesthetic, a radical move against the notion of dysphoria considered a clinical dysfunction which has historically stigmatized and therefore harmed trans bodies. In her book, Wark goes into detail in these dynamics and more, and relating it back to raving, and the raving body, as a medium—as only a media theorist of her caliber, and with her trans body and subjectivity, can do.

To illustrate this tech-free zone, a slide show of “forbidden” photos taken by Wark of the ambiance of clubs and their colorful lights appeared on a slide show on the screen (but careful to not include people), which illustrated this possibility in rather simple visual terms. Wark’s thinking, which extends back into decades and hundreds of articles and several landmark books including A hacker’s manifesto and Molecular Red as well as tens of podcasts and even sound and music art (of which the sound artwork K-time featured in transmediale’s city-wide art exhibition), is obviously much more complex than the pictures themselves, and deserves much more time than a one-hour conversation on a sofa. But sometimes, the neon-colored smoky surfaces of the image is all we need to throw us back into those spaces, and maybe the sofa is not such a bad place to talk about raving after all.

Transmediale discussion, photo by Isabel Löfgren

It was impossible not to connect Wark’s “Raving” media philosophical meditation to the backstage of several trans “figures of the night” depicted in Nan Goldin’s show, coincidentally on view one floor up at the Akademie der Künste. Much smaller than its counterpart at Moderna museet, the exhibition showed a few well-chosen series of photographs from the 1980s that throws us another kind of k-time from other nightlife formations in New York City (where Wark currently lives and raves) that are the forefathers of contemporary raves. Moving from the exhibition with photos hung on dimly lit, dark walls, and through Transmediale’s club-like décor to a pitch dark auditorium where the talk was held, provided an almost continuous experience, and where it was almost impossible to take notes in—maybe because Wark and Noorizadeh’s conversation was not meant as note-taking, knowledge-extractive opportunity, but as a space of being and listening. And while Goldin uses her own immersion to show trans pain in her photographs, in her book Wark looks for ways to write about rare narratives of trans joy. However, a fair assessment of both is that their work oscillates between the two—glints of joy amidst the pain, and excruciating suffering to achieve moments of joy.

Transitioning between these spaces somehow gave a small glimpse of how Wark navigates and inscribes herself through the act of raving (and dancing) where she has spent much time in during her own gender transition, as we learn from her writing, where reality and fiction blend together with a trans sensibility. For Wark, raving is not only a place of release for creatures of the night, a subculture, or a tech-free-refuge (but is also all of this), and maybe not necessarily a space at all. Rather, it is a practice in specific spaces in which she experiences the complex process of her own transition as a middle-aged trans person, who happens to be a media studies scholar and engages with concepts in and out of her experiences and perceptions. And vice-versa. I understand her perspective of raving looks at raving as a medium and a space of complex entanglements that mix sweat, music, identity, theory, ketamine, sex, and the act of writing and inscribing oneself in situations, which she explores in using autofiction, a writing of perceptions, and autotheory, a writing of concepts, as a method and analytic perspective. In her “autofictional groove,” she uses the concept of “surround,” the “under and around,” and with the help of Harney and Fred Moten who write “we dance in the war of apposition. We’re in a trance that’s under and around us.” Wark makes elegant and rave-like moves through her book moving from auto-, to allo-, and more interestingly to xeno, as “something invitingly strange,” in the “rave-situational proviso that what auto needs most of all is moments when it can dissipate itself, not be there, pare down to a moving part or floating notion.”

But is raving a “special” occasion? Wark flips this notion: the club scene is one of the possible refuges for trans persons to be “ordinary”—a therapeutic space which does not require “speech” as a surface, but rather dance, solidarity, and drinking water and occasional ketamine for endurance (for some). In fact, she says that psychoanalysis is a major problem for trans persons, its clinicality being responsible for decades of outright violence and trauma. Psychoanalysis is not part of her theoretical toolbox, Marxism is. Could raving then be a practice of healing, a space to resist the cooptation of bodies and subjectivities from capitalist modes of production?

At first, I thought that despite Noorizadeh’s delicate ability to instigate Wark’s thinking, that the talk show format did not really do justice to explore the complexity of Wark’s thinking. Even if the talk was agreeable, but somewhat impressionistic, sometimes we need an old school lecture to fully grasp the multi-dimensionality of a thinker. But would Wark want it that way? In hindsight, a sofa conversation might be a good format after all, but maybe in a smaller, more intimate room, with neon lights, and without the sight of several phones taking pictures and real-time tweeting which hinders a possibility for us in all soberness of a conference to experience more of k-time. Wark is a fabulous speaker filled with concepts and quirks which are generously defined in the glossary in the book—like Femmunism, enlustment, xeno-euphoria and sidechain time—which require a more immersive reading that a short talk can afford. Perhaps reading her book often feels like sitting in a sofa with her, but it is more like lying next to her in bed after a rave while she writes, as she tells us in her book. For those interested in this idea of a productive aesthetic dissociative practice, I recommend raving first, and then diving into her autofictional book, maybe even start autofictioning to navigate past multiple everydays and planetary extractions to avoid the ultimate commodification of ourselves.

Isabel Löfgren is a Swedish-Brazilian artist, writer, and researcher, currently a Senior Lecturer in Media and Communication studies at Södertörn University, Sweden. www.isabellofgren.se

[1] Lovink, Geert. Extinction Internet. Institute of Network Cultures, Amsterdam, 2022. https://networkcultures.org/blog/publication/extinction-internet/