Quarantine Dreams 2: No-Set Sci-Fi

By Helen Runting

On the 15th floor of the Westin Hotel in Perth, on the night of February 14, 2021, somewhere between 50 and 100 bodies were placed into mandatory quarantine to prevent the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Hotel rooms, lined up in rows and stacked as if in a filing cabinet, were used to place these human bodies—and their possible viral companions—in a spatiotemporal holding pattern. This was achieved by enclosing those bodies in the soft beige architecture of business travel for a period of 14 days. Like so many of the “container technologies”1 of late capitalism, the rooms were long and narrow rectangular spaces. Each ended in a wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling picture window. Beneath them was Perth, a metropolis located on the western coast of the vast Australian continent, in the same time zone as Hong Kong and 3,500 kilometers from Melbourne, my final destination—a similar distance to that between Stockholm from Ankara. The city is home to 1.12 million souls and the headquarters of a number of global mining corporations, the skyscrapers of which form visible monuments to the extractive accomplishments of 200 years of colonial, extractivist petrocapitalism in my birth country.2

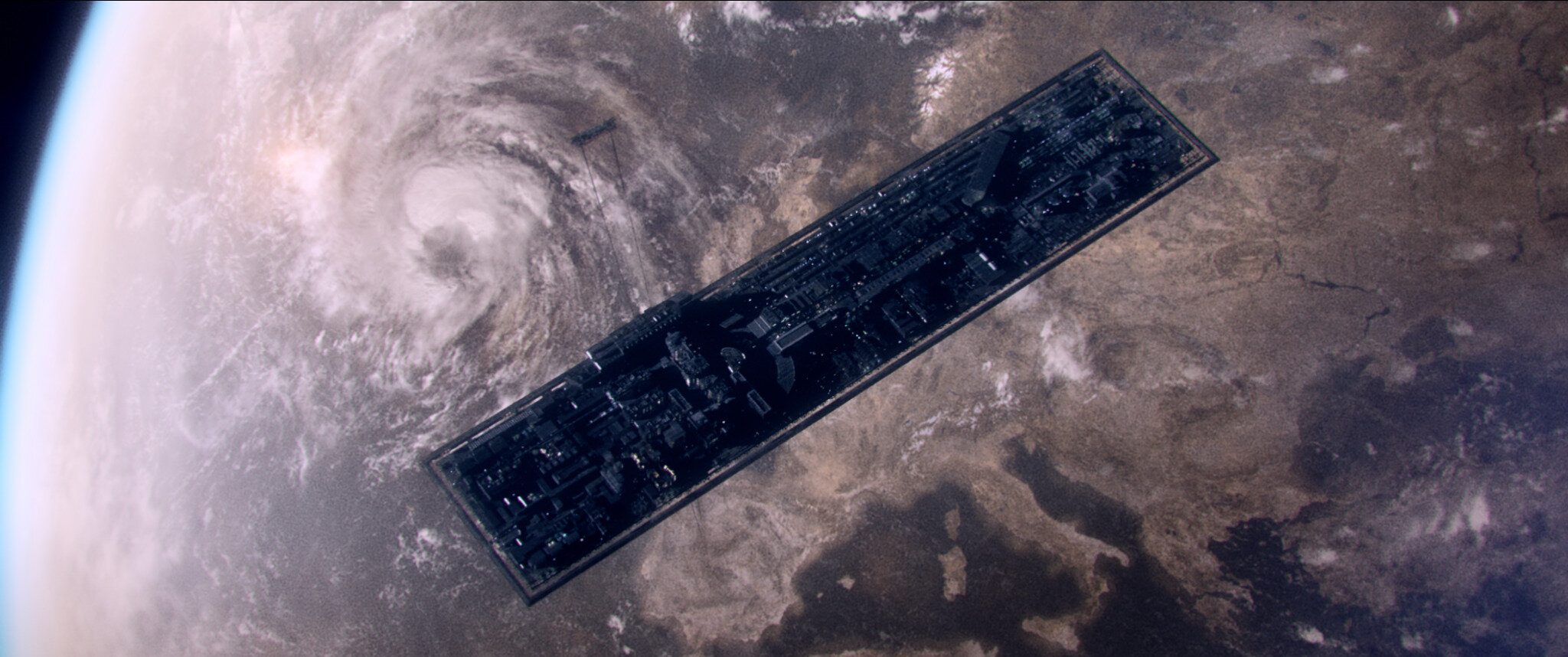

View of the exterior of the ship. Still from the film Aniara. Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja, directors. 2018. Aniara. SF Studios. Concept design: Rutger Sjögrim, Andreas Nordström, Kristina Sundin, and Fredrik Andersson.

Arrival

The hotel building appeared incongruously luxurious from the outside, given the pandemic circumstances that had deposited us there, and I wondered at first whether a grave error had been made. It was dark when we arrived. A makeshift reception desk had been set up under the mighty, marble-clad porte-cochere. Had we been mistaken for another plane-load of people—delegates, perhaps, to some international conference? International conferences no longer existed, I reminded myself. The window of my seat in the bus was in line with a window to one of the hotel’s (surely multiple?) restaurants. A chef was preparing layered deserts in cocktail glasses, topping scoops of layered parfait with whipped cream; she looked stressed and bored at the same time and not the least bit curious about the arrival of so many new guests at once. The presence of visibly armed soldiers in full army fatigues, positioned behind and ahead of the bus, attested to the fact that this was, in fact, mandatory quarantine, ordered by the State of Western Australia, and not a holiday or business travel. In the warm tropical night air, the combination of those cocktail glasses, the repurposed public transport buses, a row of bird-cage-like porters’ trolleys, the flashing blue lights of the police escort, and the guns all seemed to suggest that the aesthetics of quarantine would mirror those of a covert trade summit.

Tired eyes drank everything in, after long hours spent in the raw logistics-space of the airport terminal. There was little time to breathe the fragrant, heavy, outside air, though. Next to the reception desk was a door that led to a bank of elevators. After ascending to the correct floor, the doors opened onto a dark lobby space and then suddenly we were all in our rooms, individually packaged and ready for our period of architecturally distanced viral incubation.

Click

This was definitely one of the nicest hotels that I had ever stayed in. The relief that washed over me upon discovering this meant that I didn’t register the door closing behind me. I only heard it shut. Click. That door wouldn’t operate as a door should for the remainder of my stay: no bodies would traverse its threshold; only food, household items, and COVID-19 swabs would pass through the airspace of its frame. Otherwise, it was to be closed. On the other side was a corridor and beyond the corridor was a lift lobby where a guard sat, in full Personal Protective Equipment. I knew this because as soon as I heard the door click, I panicked, opening it immediately and walking back towards the lifts. I had to come up with something to ask this man, anything, to give meaning to my instinctual dash.

“What time is dinner?” I mumbled. It was 9pm and not a totally crazy question.

Having directed me to my room only moments earlier with the courtesy of a regular hotel employee, his demeanor transformed into something quite different. Exercising the universal body language for “back up!” (arm extended, hand facing towards me, figures spread, walking slightly backwards) and issuing a continuous stream of commands (“Ma’m-you-cannot-leave-your-room-under-any-circumstances-please-go-back-to-your-room”)—I was herded back into my room.

Scene from the room “Mimasalen.” Still from the film Aniara. Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja, directors. 2018. Aniara. SF Studios.

Neutral Cocoon

Whilst the design of hotel rooms tends to play freely with references to the cabins of boats or aircraft and even to some extent to lobbies and offices (plush chairs, stone, carpet), the palette of colors and furnishings must not at any stage remind the occupant of two other spaces of confinement: the hospital or the prison. The bed is the element that links the hotel uncomfortably to these other two room typologies, and at its most basic this is the only thing that any of these spaces need to accommodate. The bedside tables, minibar, luggage racks and wardrobes, the en suite, dining table, desk, seating area, lamps, shelves, coffee-table books, and “art”: all of these are superfluous to the prime purpose of the space—sleep (or, possibly, sex).

The particular hotel room that I found myself inhabiting at the moment of that first “click” was dressed in multiple shades of beige, a space where texture and light had been artfully deployed in order to produce the sense of a calm, warm cocoon. All surfaces were wipe-down, but carefully avoided any connotations of being sterile. The walls were treated with a textured wallpaper that imitated raw silk; wood paneling or stone facing had been used in places where bodies, luggage, or other furnishings might rub repeatedly up against them (behind the couch, at the backboard to the bed, the luggage nook, the minibar hutch). A large mirror bounced light off the blonde wood floor and white sheets. The bathroom was entirely faced in a marble-like stone, and accessible on two sides via large sliding doors that were clad in a wood veneer. The same dark wood was used on the horizontal shelving and triangular dining table.

The neutral cocoon is built on a design language of tactile superficiality. This is an interior architecture that invests heavily in the first 1 mm, in the lining and encasing of functionality. It is in these surfaces that a “smoothing” effect can be achieved: through ubiquitous, tactile surfaces, one container technology can seamlessly be replaced by another, without visible division. All the colors of an unpacked suitcase look good against beige; a tangled mess of clothes and things and body constitute simply a further layer in a hotel room. These are spaces that, it can be argued, are designed to facilitate a withdrawal into flow.3

Scene from the room “Mimasalen.” Still from the film Aniara. Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja, directors. 2018. Aniara. SF Studios.

Controlling Control

Waking on the first morning, I was struck by the lack of apparent temperature. The air temperature was perfect, just right, even when I pressed the button that opened one of the three layers of automatic curtains and sunlight streamed into the room. Outside, it was warm, somewhere in the mid-30s, and the sky was a deep desert blue.

The architectural historian Reyner Banham traces the way in which Frank Lloyd Wright’s interiors became “the international norm for hotels and motels” in the second half of the twentieth century. Whilst Wright’s houses are known for their carefully engineered, largely passive, ventilation, his use of wood, horizontal shelving, and rough-textured textiles, amongst other characteristic moves, apparently proved popular in the mechanized climatic conditions of international chain hotels. Banham attributes this to an emerging emphasis, common to both the one-off Wrightian villa and the mass-produced hotel room, on interior comfort:

“this idiom has genuine virtues—it is visually undemanding, acoustically quiet, thermally comfortable because its vegetable-fibre surfaces are quick to warm. Furthermore, these surfaces and forms seem to settle well with central heating, electric lighting or (later) air-conditioning, and they had so settled long before the style began to spread beyond the Chicago and California suburbs that gave it birth.”4

What is perhaps most interesting for the present essay in this is the link that Banham forges between such interior comfort and what he later in the book describes as Wright’s “easy mastery of environmental control.”5 Banham’s The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment was written in 1969, a moment in architectural history where critique might comprise of (cis, Anglo-American) men expressing admiration for each other’s sensibilities; the historian praises the way in which Wright “took over relevant technologies with enthusiasm without dogma, applying them as required but without prejudice to stylistic preferences.”6 That which Wright shared with the interior architects of the post-war American leisurescape and its hotels was an attitude of cheerful pragmatism regarding the delivery of “what was required”: this affinity, which was apparently was not shared with Wright’s Bauhaus contemporaries, is described by Banham in terms of an attentiveness to “the physiological responses of the consumer.”7

This is not to say that the neutral cocoon, as I have come to think about this genre of architectural space, is purely a backdrop for passive consumption. These cocoons can also be understood as radically productive: the consumption of these spaces through their inhabitation can also be experienced as an exercise in the regulation—and even production—of self and environment. 336 hours in the same interior space, under constant climatic conditions, without so much as an openable window to disturb the peace with its breeze, might sound like hell for those who enjoy what we might term conditions of “exterior comfort.” In Scandinavia, whilst the winter climate is particularly harsh, warm clothes offer a reliable solution to the discomfort caused by sub-zero temperatures; there are never days of 40-plus-degree “scorchers” that cannot be “solved” by anything other than a total avoidance of the exterior. Having grown up with the experience of such hot spells, the lack of openable windows didn’t feel hellish, given the strength of the hot sun outside. It was … pleasant. Away from gendered and gendering gazes, in static conditions of moderate warmth, flesh can be exposed. Behind UV-treated glazing, one can lie for hours in direct sunlight without getting burnt. In Australia, these things in themselves also constitute matters of control.

Dystopian Discomfort

What would have happened to our “quarantining” (a procedural concept, a little like marination or incubation) if conditions had changed? What would it have been like if the air-conditioning turned off? If the lights went out? If the food that was delivered three times a day stopped arriving? Alternately, what would have happened if something happened “out there”: if wildfires encroached on the central business district, if the internet went down, if everybody else left? How long would it be before we broke the seal of self-discipline that functioned as well as a physical lock, and began to form alliances, perhaps at first in a socially-distanced manner and then later not, as the need to find sources of heat/cold, light/shade, and sustenance was reframed as a matter of survival?

The journalist Laurie Penny has caricatured the heteronormative, hypermasculine visions of contemporary dystopian science fiction as “brotopias,” and it may be just such a brotopic scenario that I am indulging in, in entertaining this scene of infrastructural collapse.8 Penny warns of the danger of fantasies of a broken future that sanction gendered ideals of physical strength and a capacity for violence, wherein women will need to be “protected” by their male counterparts, who regain the status of provider in a new world order. The dystopian thrust of climate-change disaster-porn or zombie-apocalypse scenarios, and even to some extent feminist critiques of ecofascism like that offered by The Handmaiden’s Tale, all tend to engage with science fiction’s obsession with comfort, constructing a binary between inside and outside, which then drives the storyline forward. Often starting with scenes of hermetically sealed spaces of interior comfort (the spaceship, the Matrix, the metropolis), science fiction dwells on scenarios of ejection, whereby an occupant is thrust into an “outside” where comfort has either disappeared, been reserved for an elite few, or has morphed into something horrific in and of itself.

Photograph from the filming of Aniara. Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja, directors. 2018. Aniara. SF Studios. Photograph: Kuba Rose.

Spaceships offer the most extreme version of such a scenario, transposing an exterior that is so totally devoid of comfort that it does not support life (space, or the barren surfaces of other planets) against a hermetically sealed interior that, even if it is not “plush,” often invokes the aesthetic palette of what I earlier termed “the neutral cocoon.” The 2018 “no-set sci-fi” film adaptation of Harry Martinsson’s Nobel Prize-winning poem Aniara, which was directed by Swedes Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja provides a recent example of how environmental systems collapse can occur at the level of the interior and exterior simultaneously. The “interior,” here, as in many spaceship-based sci-fi films, is also a double-figure that takes on psychic dimensions, suggesting an interlacing of built space and subject. The collapse that Martinsson’s poem imagines thus plays out in the scenography of the film at three distinct scales: that of the Planet itself (seen in flashbacks), that of the city (transposed onto the internal organization of the spaceship Aniara), and finally that of the psyche (which tends to implode in rooms—most prominently in the “Mimasalen,” a room that has gained a degree of consciousness of its own). The film thus subjects the audience to the shock of unavoidable, unnecessary, total, systemic collapse against a banal backdrop: Baltic cruise ship interiors, shopping malls, and conference centers were used to represent the ship’s interior (rather than building sets or digitally modelling an interior in post-production).9 As concept designer for the film Rutger Sjögrim (who worked alongside architects Andreas Nordström and Kristina Sundin, and chemist Fredrik Andersson) comments, these “are places where the extraordinary and the very mundane collapse into each other. Places where the dream of that one fabulous night is repeated over and over again until everything is bleached into a grey, flavorless eternity.”10

Endless Interior

And so there we were, bathed in desert sunsets punctuated by the illuminated business signage of the global mining corporations based in Perth, in a space that was as much an envelope of cool, bright, radiation-filtered air as it was architecture—a space that in turn was directly reliant on the power (electrical, monetary) signified by those signs. And we were alone.

The idiom of interior comfort that Banham locates in Wright’s villas, which is echoed in the archetypical generic hotel room, is a way of organizing interiors that “derives from a shift of emphasis from exterior show in domestic architecture to interior comfort in domestic environment.”11 It didn’t much matter what form such comfort took on the outside when the systems that delivered it began to reach mass-consumers of architecture in the American post-war suburbs. As Banham puts it, “That emphasis could be packaged in any number of ways, largely because the package was becoming rather irrelevant.”12

Like the spaceship, the hotel room of hotel quarantine is all interior. We had been transported to the hotel without warning in the late evening; as such on that first day, as the sun’s rays extended lazily across the warm blonde wood floor, I had to Google the name of the hotel to get a sense of how many more floors might be above or beside me: to understand the extent and form of the “rather irrelevant packaging” that was the building envelope. I had never thought about the fact that life on a spaceship would present a similar problem: without a view from the exterior, the form of the spaceship becomes meaningless. The CGI views we see in sci-fi films are a fiction I had not previously thought to question.

Photograph from the filming of Aniara. Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja, directors. 2018. Aniara. SF Studios. Photograph: Kuba Rose.

Quarantine may also be thought of a form of “no-set sci-fi,” whereby the exterior world is momentarily removed, and the interior is repurposed for another kind of narrative. Far from the incarcerating logics of the prison, this removal does not come with expectations of betterment, atonement, or punishment: whilst disciplinary processes of subjectivation, to employ Michel Foucault’s terms, are present (remember: the doors were not locked), they are not aimed at producing in the inhabitant an ideal citizen, entrepreneur, woman, or any other form of “docile body.”13 Rather, the inhabitant is just another container: in the nested, “neutral” cocoons of quarantine, bodies are stored that are in turn also treated as storage devices—rather than guests, they are hosts, enclosing the real “hotel guest” within them: the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Helen Rix Runting is an architectural theorist (PhD. Arch) and urban planner; she is co-founder of the Stockholm-based architecture office Secretary, co-editor of the public art project Stockholmstidningen, and Research Fellow in Architectural Theories and Critical Practices at the Melbourne School of Design at the University of Melbourne.

1 See: Zoë Sofia, “Container Technologies,” Hypatia 15, no. 2 (2000).

2 I take the term ”extractivism” from Matthew Ashton, ”Sand: Four Acts,” in PLAN 1-2 (Spring 2020), 23-36. See also: Sandro Mezzadra and Brett Neilson, “On the Multiple Frontiers of Extraction: Excavating Contemporary Capitalism,” Cultural Studies vol. 31, issue 2-3 (2017).

3 In the essay ”White, White, and Scattered,” I note, with my co-author Hélène Frichot, a double move that comprises of ”a retreat into ‘place’, into the building of worlds via the dressing of interiors (a nesting impulse)” and ”a withdrawal into flow, an aestheticization of privileged itinerancy and a valorization of the possibility of remaining in motion.” We go on to argue that ”Both forms of retreat beat a path away from that which is radically shared, into the comforts of a heavily curated interior.” See: Helen Runting and Hélène Frichot, ”White, White, and Scattered,” This Thing Called Theory, eds. Teresa Stoppani, Giorgio Ponzo, George Themistokleous (London: Routledge, 2016), 231-241.

4 Reyner Banham, The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment (London: The Architectural Press, 1969), 94.

5 Ibid., 121.

6 Ibid., 122. Emphasis added.

7 Ibid., 124.

8 Laurie Penny, ”Feminism Against Fascism,” talk presented at Sonic Arts Festival ”The Noise of Being” at De Brakke Grond, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, (February 26, 2017), https://vimeo.com/209623897.

9 I note that Rutger Sjögrim is one of the three partners in the architecture practice Secretary, along with the author and architect Karin Matz. Thanks to Rutger Sjögrim and Andreas Nordström, as well as directors Pella Kågerman and Hugo Lilja for introducing me to the notion of “no-set sci-fi.” Pella attributes the concept to film commissioner Baker Karim in the newspaper article: Miranda Sigander, “Sexkult och ångestshopping på sista rymdresan,” Svenska Dagbladet (January 29, 2019), https://www.svd.se/sexkult-och-angestshopping-pa-sista-rymdresan.

10 Rutger Sjögrim, “Aniara: Concept Design and Research for the Motion Picture Aniara,” accessed June 28, 2021, http://secretary.international/aniara.html.

11 Banham, The Architecture of the Well-Tempered Environment, 95.

12 Ibid. Emphasis added.

13 Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1991).