Exhausting (Architectural) Theory, Noopolitics, and the Image of Thought

By Hélène Frichot

Preamble to the Exhaustion of our Architectural Concepts

In an essay in the Harvard Design Magazine in 2005, the architectural theorist Reinhold Martin lamented that it is now with some embarrassment that we mention the name Gilles Deleuze.1 The ‘we’ here identifies architects and architectural theorists alike who nevertheless remain ‘haunted’ by the legacy of this French thinker, whose very name persists today as a refrain of sorts. Although Martin’s contextual bias pertains to American architectural discourse, he speaks from a geopolitical location of considerable influence with respect to the reception of Deleuze into the discipline of architecture. Martin announces this affective embarrassment, which we might also call shame to indicate one of the more powerful affective registers, from the midst of the post-critical or projective debate.2 This is an already well-rehearsed discussion whose back-history includes architectural thinkers and practitioners such as K. Michael Hays and Peter Eisenman (in opposing camps), and which is then reformulated by the following generation – Martin notes that the debate is quite Oedipal in its development.3 It is a debate enunciated quite vehemently by Michael Speaks, and also by Sarah Whiting and Robert Somol who place an emphasis on action over observation, speculation over erudition, and getting something going, that is to say, jump-starting a ‘projective architecture’.4 Contesting camps begin to emerge, those calling for a post-critical turn, who share a commitment to an “affect-driven, nonoppositional, nonresistant, nondissenting, and therefore nonutopian form of architectural production”, that is ‘cool’ and ‘easy’, at least according to Martin and George Baird.5 And then there are those, such as Martin, who hold to the utopian possibilities still sheltered within critical thinking. All of the above voices share one thing in common: whether explicitly or implicitly, they have taken recourse to the thinking of Deleuze. It would also seem that Deleuze can be deployed irrespective of which camp you identify with, making him appear a remarkably versatile thinker. The shame in naming him in fact returns us to both family relations, that is to say, who we hold to closely as our forefathers or precursors and how we are either overshadowed by them, or else how, recognising the burden of influence, we nevertheless “restore an incommunicable novelty to our predecessors”.6 Surely it’s worth an attempt? In the meantime, and as Baird has intimated, perhaps the overweening influence of the “American East Coast” on what (architectural) theory we choose to read has also finally shifted.7

Even though the joyful, sometimes giddy discourse and full toolbox of concepts that have been appropriated from Deleuze and also Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s oeuvre over the last thirty or so years, with a peak in interest through the closing years of the last millennium, have provided many in the discipline of architecture with an indispensible critical and creative apparatus, yet it now seems, at least in the context of architecture, that one must remain wary of mentioning their names. No doubt this amounts to a form of a disciplinary hang up, but it does not auger well for a book arriving late on the scene that dedicates itself to Deleuze and his ‘connections’ with architecture.8 Such a collection as Deleuze and Architecture situates itself well after the exhaustion has set in, when just to make reference to Deleuze risks the retort that one is handling an anachronism, that, as one architectural colleague in Melbourne put it to me: “we already did Deleuze in the ‘80s, what more is there to be done with him?”; and as another well known feminist reader of Deleuze remarked “I think I have exhausted all there is to say about Deleuze and architecture…”. This too will be an essay that comes too late, that situates itself unfashionably in the rear-guard, that thinks too slowly, and that is, after all, operating in the proximity of worldly exhaustion.

A Methodology of Exhaustion

It is exactly the space and pace, the local and global extent of exhaustion that I wish to explore again in this essay.9 In the introduction to Deleuze and Architecture, and in other of my writings,10 I have extracted a methodology of exhaustion from Deleuze’s brief and dense essay “The Exhausted”, so removing and abstracting it, without some attendant risks, from the specific application he has tested in his reading of Samuel Beckett’s novels, plays and television plays.11 Below I will address the way Deleuze enumerates four ways of exhausting the possible, accepting that this list should not be taken as exhaustive. I should also admit that I have wilfully extracted these four approaches from what Deleuze identifies as three ‘Languages’: Language I, II, and III respectively. It is important to note, as I will elaborate, that the results of the methodology of exhaustion can proceed toward a more powerful composition of forces, as well as toward a decomposition of our relations and encounters amidst our local environment-worlds. That is to say, the methodology produces what could be judged as both ‘failures’ and ‘successes’, but this very much depends on point of view and situation. Although in Deleuze’s argument the methodology seems to progress from exhaustive series or ‘combinatorials’ (of concepts, things, images,) toward the dissipation of the power of an ‘image of thought’, I will argue that it is more useful to see what happens when the methodology is followed in both directions. The four approaches to a methodology of exhaustion include: 1) the composition of combinatorials arranged through the formation of exhaustive series (of concepts, images, things, any such thing that can be named); 2) the drying up or exhausting of the flow of weak and strong voices; 3) the extenuation of the potentialities of space by way of the any-space-whatever, as well as exhaustion via images; 4) and finally, the dissipation of the power of the ‘image of thought’, which as an iconoclastic moment leads either to a new more positive image of thought or else to a more dogmatic one. It is also worth mentioning that there is a mathematical and geometrical definition of a method of exhaustion that allows the area beneath a curve to be calculated by approaching the problem of exactly measuring curvature without, strictly speaking, arriving at anything more than a sufficient answer, creating what might be called a working method. To be exhaustive, in the sense of a search party, is to search an area as completely as possible, but there is always the suspicion that some thing still remains to be unearthed, or that we missed some crucial detail. And so the search may well be taken up at a later date. Crucially, and as will hopefully become clearer, the methodology of exhaustion as well as confronting the dissipation of sense, also leads to the breakdown of the organic or inorganic body, defined in the broadest way to include, for instance, a human body, a body politic, a built environment-body, an ecological body, and so forth.

I will now develop each of the four levels of the methodology of exhaustion in more detail, before venturing an argument concerning the methodology of exhaustion’s noopolitical implications for worldly and global exhaustion.

1. The formation of exhaustive series

Deleuze names this first moment of the methodology of exhaustion Language I, and suggests that it is concerned with forming series or combinatorials in such a way that simple enunciation replaces the proposition. No hypothesis, no thesis, no statement even, simply a tireless enumeration of items, as though the act of naming could secure a proprietorial right, much as the first man Adam claimed all the creatures of the world by anointing them with names. A combinatorial is achieved through the enumeration of a list of names, which admit no inherent association, instead a series is created through the simple fact that its members have been denominated. And the things so serialised (whether they are material or immaterial things, concepts, or even images) are only gathered in so far as they can be named. Language names the possible, and without being named via language a thing cannot be included in the series, according to Deleuze.

The important point to stress here is that series can be composed of concepts or things, and also images (as distinct from an image of thought), and then it is a question of what happens when series are produced sufficient to create an image of thought that imposes its noopolitical effects. From combinatorials of words, things, images, any such thing that can be named, Deleuze confers on this capacity for naming the role of a metalanguage, but it is a cut-up, atomised language, one of sound bytes, and disjunctive morsels bearing no associative relation. A stabilised surety of signification, importantly, is also renounced, as an exhaustive series does not allow us to rest on a secure signifying relation. The capacity for naming exhausts the possible in so far as a name also behaves like a form of branding, an acquisitional (trade)mark that is impressed upon an image, thought or thing, claiming it as (private) property so that its use cannot be taken up freely by others. As Lewis Carroll (and Deleuze after him) playfully expounds in the conversation between Alice and the Knight concerning what the name of the song Haddock’s Eyes is called, as distinct from the name of the song, as distinct again from what the real name is, as distinct finally from what the song is called, naming also exposes us to the risks of an infinite regress of sense or indefinite proliferation.12

2. The drying up or exhausting of the flow of voices

Even this so-called metalanguage and the power of naming can be exhausted. Here we arrive under the purview of Language II, the sounding of weak and strong voices, and the compelling notion of speaking as a foreigner in one’s own tongue (an oft-repeated refrain from Deleuze and Guattari, which they have appropriated from Marcel Proust): “The necessity of not having control over language, of being a foreigner in one’s own tongue”.13 The aim of which is to bring “something incomprehensible into the world.” These voices can be described as waves and flows that distribute words as linguistic corpuscules, as voices always in the process of becoming estranged and garbled. The voice that speaks is always the Other, because it is always the Other who speaks first, which is simply to say that the symbolic order always proceeds us, and we necessarily come slowly, even stupidly to language. These voices inaugurate the emergence of other worlds, constituted by stories, and “inventories of memories”.14 Who speaks these stories? If it is I, then where do I include myself in the historical development of these stories? According to Deleuze, an aporia is located in this will to situate one’s own position in the story, to discover a small (discursive) space that has not yet been exhausted. Running up and down the series composed by the combinatorials of Language I, in search of a beginning or an end, only to realise that the limit of the stories, their point of exhaustion, can be located anywhere along the series. The stories are always already exhausted even before one ventures to speak, but speak one must. Between two voices as a minimum, a point is reached “well before one knows that the series is exhausted, and well before one learns that there is no longer any possibility or any story, and there has not been one for a long time.”15 Recall again the embarrassment of which Reinhold Martin speaks, suggesting that the voices of architectural theoretical discourse have quite exhausted the name ‘Deleuze’, challenging the architectural theorist’s capacity to speak further, as well as challenging the discipline of architectural theory itself.

3. The extenuation of the possibilities of space

Language III, following on from exhaustive combinatorials and exhausted voices, is that part of the methodology of exhaustion where language is no longer used to denominate innumerable objects, or to transmit voices, but is entirely dissipated in a confrontation with immanent limits, which Deleuze describes as “hiatuses, holes, or tears” seemingly received from an “outside” or “elsewhere”.16 With Language III, the relationship with language is effectively stretched to its limits. To arrive at an image of thought via Language III, one proceeds through what Deleuze has named an any-space-whatever, which is the extenuation of space.17 Space, conventionally defined through extensive measurements enables the demarcation and determination of localized places and their respective assemblages of singularities, “a sample of the floor, a sample of the wall, a door without a knob, an opaque window, a pallet…”,18 so supporting the taking place of some event. Yet, “To exhaust space is to extenuate its potentiality by making any encounter impossible”.19 In Cinema 1, Deleuze describes the any-space-whatever in relation to post-war towns, apprehended as disconnected, empty spaces.20 In detail he also describes, across a selected series of cinematic images, how the any-space-whatever is composed or rather “extracted” from a given state of things, through means of light, shadow, white and colouration.21 Of interest here is that the methodology of exhaustion also pertains to spatial exhaustion.

In addition to spatial exhaustion or attenuation, Language III includes the labour of image making, and this is where Deleuze suggests that making an image is a very difficult thing to do. Images in this sense must be distinguished in two directions, they are distinct from those found or received images, which alongside things, and concepts, might be enumerated and named or even ‘branded’ within combinatorials under Language I, but they are also distinct from the ‘image of thought’, which organises how it is we come to think that…as a matter of course, and without further reflection. The any-space-whatever and the images treated in Language III finally lead to an encounter with the image of thought, which is not some representation of an object or a subject, but a movement of the mind suggestive of all manner of noopolitical effects, of which more will be discussed below, suffice to say that noopolitics takes advantage of our collective, unreflective habits of thought, or ‘opinions’.

4. The dissipation of the power of the image of thought

By suggesting a fourth level here, and that is the dissipation of the power of the image of thought, I take certain liberties. There is no Language IIII in Deleuze’s essay “The Exhausted”. I argue nonetheless that this is where the methodology clearly leads (also keeping in mind that the methodology runs in both directions). The dissipation of a dogmatic image of thought either enables the installation of yet another hegemony, or else opens the way for the production of a new image of thought. As Deleuze and Guattari explain “The classical image of thought, and the striating of mental space it effects, aspired to universality”,22 but a new image of thought may promise other possibilities. The image of thought as conceptual construct is discussed at length in Difference and Repetition, Nietzsche and Philosophy, and also in Proust and Signs. In Difference and Repetition, Deleuze offers eight postulates that pertain to the dogmatic image of thought,23 and in Nietzsche and Philosophy, he offers three theses,24 as well as the possibility of a new image of thought. The eight postulates and three theses reiterate many key points, pertaining to assumptions concerning the inherent ‘goodness’ of good sense; the assumed universality of common sense; the way we presume the best intentions of the thinker who is supposedly always in search of ‘truth’; and that in the search for truth an adequate method is necessarily secured, which, of course, serves to ward off error. Deleuze places all these presumptions in crisis through his interrogation of the dogmatic image of thought. Yet in both What is Philosophy? and Nietzsche and Philosophy, there is the glimmer of a new image of thought to counter the dogmatic one. Likewise, I argue, in “The Exhausted” the image of thought flashes up briefly and ambiguously, it is an allusive opening that glimmers, appearing to offer fleeting shelter, or else some promise of a much needed shock to established thought.25 The image of thought emerges from the any-space-whatever as the any-space-whatever gives way to images. The image here “is precisely not a representation of an object but a movement in the world of the mind”.26 Precisely “what matters is no longer the any-space-whatever but the mental image to which it leads”.27 It is unclear in this context whether the image about which Deleuze speaks is, strictly speaking, an image of thought. Still, this ‘mental image’ does lead to an encounter with a dogmatic image of thought and the promise, as I have suggested, of a new image of thought that suffices to shake up the status quo, allowing something different to emerge. A distinction pertains between the noopolitical power of received and ubiquitous images (serially spewed forth), and the difficulty of creating an image that does not merely represent some object or pre-established idea, and how the former cements a dogmatic image of thought, while the latter may contribute to a new image of thought.

An Exhaustive and Exhausted Environment-World

Why might exhaustion be a conceptual theme of interest, and why in the form of a methodology? As Deleuze puts it, “The problem is: In relation to what is exhaustion (which must not be confused with tiredness) going to be defined?”28 The methodology of exhaustion alerts us to the many crises of our local environment-worlds. Exhaustivity and exhaustion together present us with urgent ecosophical questions such as the over-consumption of our environments performed via what I have elsewhere called processes of gentri-fictionalisation,29 but also via global warming, population expansion, species extinction, post-peak oil, and a long litany of contemporary plights. Depending on which direction is taken through the methodology of exhaustion, the point of departure either proceeds from the exhaustive combinatorial of concepts, (received) images, things, toward the dissipation of the image of thought, or else, the methodology commences from an encounter with an image of thought and what we make of it, and even the creation of those hopeful images and concepts that assist in the establishment of an affirmative image of thought, thence proceeding again towards series of concepts, images, and things. This reversibility of the methodology of exhaustion as it pertains to the image of thought becomes most clear in Deleuze’s books on the cinema where he explains (by way of Artaud) that the image has as its object the functioning of thought, and that the functioning of thought brings us back to images and their powerful organisation as an image of thought.30 Again, the methodology of exhaustion can operate in both directions, but notable in Deleuze’s presentation where he studies Beckett’s television plays is the way the methodology results in the iconoclastic gesture of the dissolution of the power of the image of thought.31

Exhaustivity, as Deleuze explains, demands that one combine the variables of a situation, but by renouncing any preference.32 A logical process of exhaustivity, and its production of relations of sense (or sense-making procedures), suggests a compositional method that resists hierarchisation and even judgement: Any choice is as good as any other, though we need to make ourselves worthy of the choices we make, as Deleuze emphasizes in a stoic manner.33 As Deleuze also argues in Cinema 1: The Time Image “If I am conscious of choice, there are therefore already choices I cannot make, and modes of existence I cannot follow – all those I followed on the condition of persuading myself that ‘there was no choice’”.34 Choice is established over again with every choice in such a way that what is at stake is situated anew each time a choice is made. This question of choice draws attention to an ethics, or more specifically, an ethico-aesthetics of the encounter, which returns us to the question of what we do once we have run through all the things it is possible to name (or else, brand, colonise or claim dominion over), when our discursive voices are exhausted (and thus no longer capable of critique), and we have extenuated the possibilities of space toward a limit point of de-potentialisation (of, for instance, all worldly resources, all human relations).

Exhaustivity and exhaustion together present a working method that enables us to engage in what to do with concepts and images, how concepts can be constructed, and how we can struggle to make an image, to compose a thought, from time to time that could really transform us and our environment-worlds.35 To make a novel image of thought, and not recite a ready-made one is difficult work, and there is always the threat of failure, or else corporeal or material exhaustion including the body that is our built environment, and ourselves as social collectives. An image of thought enables the capture (more or less fleeting) of sense and sensation, or the powers of affects, percepts and concepts, and this capture or composition either offers a glimmer of liberation or else reinforces repression. Contributing to the formulation of an image of thought is the construction of concepts, again leading us from one end of the methodology to the other, from concepts toward an image of thought, and back again by passing through exhaustive series, the drying up of voices, the extenuation of space. Success may well be measured by whether a dogmatic image of thought is overturned, installing in its place a new image of thought, a paradoxically iconoclastic gesture. There is also no guarantee that the ‘new’ or ‘novel’ will not in time also become dogmatic, a restored hegemony.

As I have stressed above, it is not possible to speak of exhaustive series either of words, images, nor of things without also speaking of the existential and physiological comportment of exhaustion, that is to say, the exhaustion of the corporeal body amidst material states of affairs, which Deleuze describes as follows: “One remains active, but for nothing. One was tired of something, but exhausted by nothing”.36 Further, “One can exhaust the joys, the movements, and the acrobatics of a life of the mind only if the body remains immobile, curled up, seated, somber, itself exhausted…”37 That is to say “exhaustion (exhaustivity) does not occur without a certain physiological exhaustion”.38 The material mixtures of the corporeal stuff of a body and the event of sense cannot be extricated, they are co-dependent, co-constitutive registers. It is always a question of “The exhaustive and the exhausted”,39 and how these work together, organizing the proliferation of events of sense and material mixtures of bodies as independent, yet co-constitutive series (again, according to a Stoic logic of sense). As Deleuze explains “a keen sense or science of the possible, [is] joined, or rather disjoined, with a fantastic decomposition of the self”.40 Disjoined, as sense and the body or self, although reciprocally constituted, have a paradoxical relationship of inclusive disjunction. The methodology of exhaustion, the exhaustive and the exhausted, is also supported by the well-known, even industrialised, conjunctive work of the ‘and, and, and’, producing a stuttering that manifests in the body as it practices its compositions of exhaustive series. Exhaustivity is an approach that produces a serial thinking with AND instead of thinking IS,41 and is also the organising principle of the seemingly unlimited series of the Deleuze Connections series in which Deleuze and Architecture is situated.

Exhaustion and Exhaustivity in their relation to Noology and Noopolitics

The methodology of exhaustion can be said to operate specifically in relation to the registers of space and power, but displaces ideology for Deleuze’s concept of ‘noology’. The methodology does this by way of the politics of affect it arouses, producing noopolitical effects. Rather than ‘ideology’, what I propose here, after Deleuze, is ‘noology’, which presents us with a more contemporary image of thought pertaining to a global situation of information and communication exhaustion, in the sense of near complete saturation. Noology, the logic of minds (nous), is another term for what Deleuze calls the ‘image of thought’, as has hopefully become evident above, this is an ambivalent concept that can enable either affirmative socio-political relations or else oppressive ones, depending on what use is made of it. Most often it would appear that the image of thought is that which must be destroyed, exactly so as to liberate a counter thought, but sometimes it also seems that constructing a new image, contributing to an alternative image of thought may be beneficial. Where noology pertains to the image of thought, whether dogmatic or liberatory, and its relation to ‘thinkables’, noopolitics pertains to the capacity, so easily abused, of the collaboration of minds working together, whether wittingly or not, across a local context or a global network. We are by now familiar with geopolitical tales of how our collectively produced data is sold by service providers to government organisations boosting global surveillance programs.42 In noology we have a certain operational logic of thought, and an expanded definition of mind and brain, and in noopolitics, there can be considered the social and political implications of how noology manifests in different concrete occasions.

Noology, following Deleuze and Guattari, can be defined as distinct from an ‘ideology’, and also from a ‘phenomenology’, because it does not assume an external thought imposed upon a subject (ideology), nor a stable consciousness who thinks (phenomenology), it comes neither from without not within, neither from object nor subject, instead noology identifies what stirs on the level of the pre-subjective or pre-objective, and in this way can also be related to discussions concerning pre-personal ‘affect’. “Noology is the study of images of thought and their historicity),43 this in turn suggests powerful political implications pertaining to the way we construct worlds. As Claire Colebrook argues: “noology assumes that if images of thought can be created, they can always be recreated, with the ideal of liberation from some proper image of thought”.44 Noology, where applied as a counter-thought that enables an escape from a dogmatic Image of Thought, imagines thought carried beyond the human, toward the posthuman, but noology gets easily tied up with the concrete, empirical situation of a noopolitics, and the insistence of a contemporary image of thought from which it is extremely difficult to escape. As Deleuze and Guattari stress “the less people take thought seriously, the more they think in conformity with what the State wants.”45 State here might also be replaced with the name of a multi-national corporation, Google, or Facebook, perhaps? Or else, the name of a multi-national bank, or a big advertising agency, where marketing executives have taken over the task of constructing ‘concepts.’ To counter an image of thought, there is the violence of ‘counter thoughts’, arriving from outside thought, that is, a thought from the outside or chaos pure and simple.

The affective labour of images, and how they operate in a reciprocal, if disjunctive relation to the concepts and discursive statements architects enunciate, produces a disciplinary image of thought. This has less to do with the representational quality of imagery, or ‘representation’ per se, than the power of images to procure affects, and how a politics of affect needs to be considered. It is very important to understand that images do not stand by themselves in isolation, there is no such thing as a glossy architectural image that can be taken as a thing in itself, because images operate within animated networks or assemblages involving all manner of things and relations: “The image is not an object but a “process””.46 The risk I identify is how easily such images prescribe realities, foreclosing how future peoples, places, things and their admixtures might express themselves. A relationship of near indiscernibility can be posited today between images composed to portray the privileged point of view of an architectural project, and images dedicated to the commodification of worlds through branding and marketing strategies. Less than their representational power, the images that circulate amidst assemblages that collapse the distinction, for instance, between architecture and advertising, operate through the production of affective atmospheres. In these instances, rather than an exhaustion of the image, an increasingly insatiable thirst is generated toward the ever more rapacious consumption of images: thus exhaustive combinatorials of images, each in term depending on the fact that previous images in the series are only partially or not at all recalled, through a serial amnesia of forgetfulness and distraction, or an inbuilt redundancy of the image.

The capturing of opinions, which the cognitive or immaterial labour of image making contributes to, can be described by way of noopolitics, or how minds (nous) collectively produce a politics of affect and in turn a dogmatic or hegemonic image of thought. As Deleuze and Guattari explain “we constantly lose our ideas. That is why we want to hang onto fixed opinions so much. We ask only that our ideas are linked according to a minimum of constant rules.”47 We can also assume that there would not be this minimum order in ideas, if there were not some order in things and states of affairs. Yet the combinatorials of Language I, the first level of the methodology of exhaustion do not even go so far as an associationism based on resemblance, contiguity, causality, all of which already assume some signifying capacity, or a capacity for significance, connotation, and denotation to take hold. It is the zero limit condition, minimum amount of sense that pertains, as all that is left is an additive process, one thing after the next. The combinatorial is an asignifying regime. As Deleuze has stressed, no preference is expressed whatsoever, no inclination, any choice is as good as any other, until we arrive at a point of exhaustion where we discover, after all, that we have no choice at all. Is this another way of characterising the neoliberal capitalist market place of images and concepts and its logic of accumulation for the sake of surplus and that is all?

‘Immaterial’ or ‘cognitive labour’, as Maurizio Lazzarato explains, is that labour which produces the informational and cultural content of a commodity, or that labour which is dedicated to fixing aesthetic norms, tastes, fashions, consumer norms, and thence opinions.48 It is a contemporary situation in which architectural images are circulated, received and consumed, following much the same circuits as advertising imagery and increasingly populating our Web 2.0 online worlds. Emerging networks of information and communication generate new logics of representation at a distance that operate as noopolitical apparatuses, systems which emerged with the onset of mass-media at the end of the nineteenth century, and which can be discovered in such seemingly innocuous forms as the daily newspaper.49 While the idea of a collaboration of minds (and their collectivised images) might seem a powerful and even a politically emancipatory one, the risk is that our brainpower comes to be resourced so as to better track, map and analyse consumer demand in order to stimulate ever greater demand, not to mention more nefarious ends within what has come to be called our societies of control.50 Such imagery populates our existential territories, and we, in turn, become increasingly sophisticated and adept in our image literacy, but what cannot be underestimated is the power of the circulation of affect produced through imagery, and its resultant politics. The affective atmospheres procured by way of both architectural and advertising imagery contribute to a ‘noopolitics’ that results in insatiable over-consumptions of our local and global environment-worlds.

We need to radically revise our critical imaginaries so that we can better grapple with the symptoms of ‘neural capital’ that can be witnessed at work in the image of thought where it most dangerously constrains what it is possible to think.51 The challenge, as Deleuze argues, of a true critique and true creation are the same: “the destruction of an image of thought which presupposes itself and the genesis of the act of thinking in thought itself.”52 Here we see how the image of thought is treated ambivalently by Deleuze, sometimes raised as a possibility, sometimes destroyed in favour of what is ‘thinkable’, as such, which nevertheless eventually leads us back to the establishment of yet another image of thought.

Exhausting World and Globe: Two Final Images

In an essay for the journal Radical Philosophy, Peter Osborne reminds us of an important distinction between globalisation and worlding, or between ‘globe’ and ‘world’.53 Osborne defines ‘globalisation’ as the effect of the relative global deregulation of capital markets, including the denationalisation of the regulation of markets in finance capital, the implication of which is the evacuation of a social component, resulting in a conceptual space that has no social occupant. He is cautious to warn that there are many rich accounts of globalisation, but he wants to complicate the above definition and its evacuation of the social with the Heideggerian existential-ontological notion of ‘worlding’, and then complement this with Jean-Luc Nancy’s preferred formulation of globalisation, that is, ‘mondialisation’, which ties a line between globe and world. What this facilitates is a complication between the globe, on the one hand, as that exhaustive geometrically spherical expansion that extends all the way to infinity, associated as it is with notions of infinite perfection. And on the other hand, the world, or existential engagements of multiple, located worldings, which pertain to finitude and material exhaustion. Here, though, “environment-world” (umwelt) is my preferred formulation, appropriated from the idiosyncratic writings of Jakob von Uexküll,54 and suggesting a real territorial blindness between one bubble of existence and the next. The collapse of globe and world, for my purposes, leads to the intersection between exhaustion and exhaustivity. Two images can be presented in conclusion to perform the collapse of exhaustion and exhaustivity, processes of quasi-subjective environment-worldings and quasi-objectifying processes of globalisation.

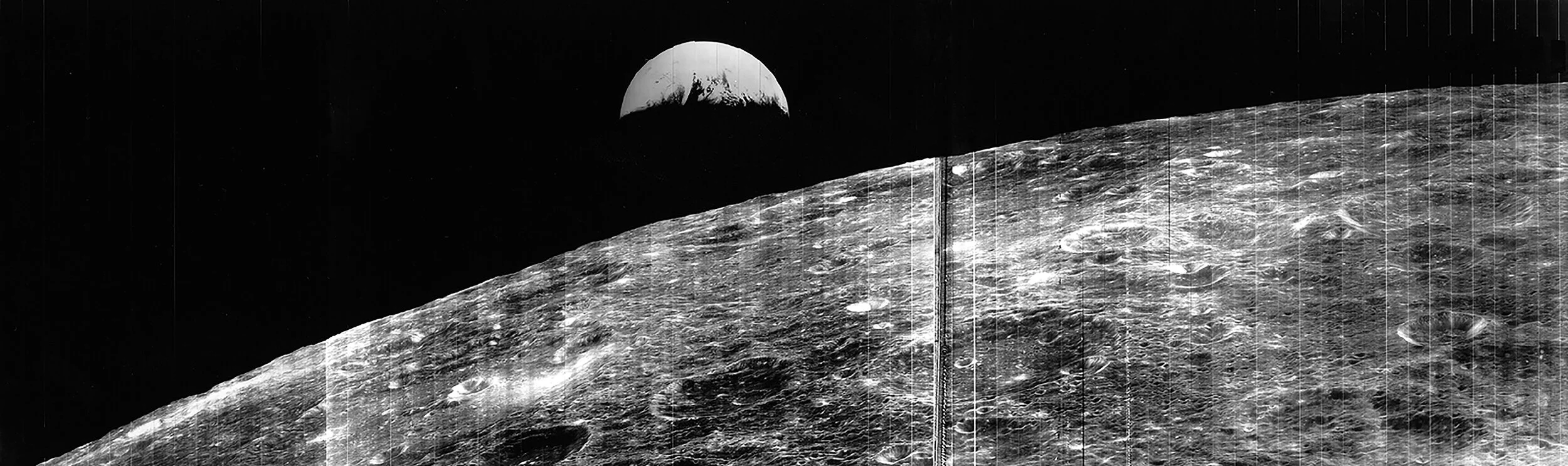

Lunar Orbiter 1 new of the Moon and crescent Earth, August 23, 1966. Image Credit: NASA

Image 01 - Still, the World: There is an oft-remarked-upon inaugural image of the planet Earth as quiet blue sphere, an exquisite blue marble rising over the crest of the moon viewed from the portal of the Apollo space shuttle on December 24 1968 by human eyes, and reproduced through the formerly mechanical means of photography.55 It is an image of the world presented all at once, communicating something of a satisfying wholeness. It is also an image as form of witness to the stunning possibility of a final escape from intimations of an exhausted world. And at the same time an image that says, we are no longer sheltered within a celestial sphere (as imagined by the ancient Greeks), but looking back down from a great distance above, we are outside, or at least on the threshold of some incomprehensible outside.56 Still, there remains something of an environment-world at work here, together with this presentiment of corporeal exhaustion.

Copernicus: Global Monitoring of the Environment, Sentinel-1A. Screen shot from introductory video. Image Credit: ESA (European Space Agency)

https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/Copernicus/Overview3

Image 02 -Total Globe Scan: By the 24th of April 2014 the European Satellite Sentinel 1A had completed its first test scan of the planet Earth after two weeks in orbit as part of the new Copernicus program for full Earth observation, a cooperation between the European Commission, the European Space Agency, and an industrial consortium.57 The plan is that this satellite will soon be accompanied by a fleet of other, similar, unmanned satellites, all dedicated to the task of a total globe scan, to be repeated at regular intervals. The best of intentions are, of course, presumed here, because good and common sense dictate that the thinker, pursuing appropriate methods, necessarily goes in search of the truth and thereby avoids error. The images produced, of apparently “unprecedented accuracy”,58 are supposed to become open source, available for the benefit of all (or at least for the benefit of ‘citizens’), that is to say, this will not devolve into the kind of dystopian fantasy depicted in such movies as Enemy of the State (1998). Further, these images can be used to detect and measure the rate of melt of the polar ice caps, and also identify where tankers have spilt their oil into our oceans. And yet, a more subtle implication is suggested in this unlimited series, or combinatorial of remotely sensed images recursively collected toward the production of a an ever-renewed composite image of the/our globe/world (with or without a social component?) and that is the achievement of near unlimited exhaustivity. The (remotely sensing non-human) search party will be exhaustive, no stone will be left unturned. A scan is like a series of images with no inherent association, but once placed alongside each other, framed by the weak and strong voices of discourse, made operational toward the extenuation of space, the potential is that this total globe scan will yield a powerful noopolitics.

Postlude to Critical Architectural Theory (and Practice)

The above methodology of exhaustion, followed by a discussion of noology and noopolitics, and then these fleeting final images of exhaustion and exhaustivity do not lead us back to the opening discussion of the near-contemporary situation of architectural theory, or more specifically, critical architectural theory and its vicissitudes. A tension is left unresolved between critical reflection and Reinhold Martin’s call for a ‘realist utopia’, and then the enthusiasms of a projective architecture, with its proposed new image of thought, so cool and easy. Perhaps another approach, which by no means attempts any kind of synthesis between these positions, might be offered in what Helen Runting and Fredric Torisson in a series of unpublished co-written papers have called “projective critique”. They posit the ongoing necessity of critiquing the project, but not restricting this critique to architectural aesthetics alone. Instead they suggest it is a matter of situating an architectural project in a political ‘real’ of capital flows and the rise of experience economies, which presumably also means to expose the project to the interface between the relative comforts of environment-world and the depersonalised hold of market capital driven processes of globalisation. This approach also issues a wake up call to a politics of affect, of which not enough has been said above, that is, it remains crucial to ‘feel’ the (architectural) project while questioning it, this being a double-move of inhabiting a project, as well as querying our own affective responsivity. I’m told by Runting and Torisson that the strategy of “projective critique” discovers uncertain closure in a blur, suggesting another affective register, this time quite atmospheric or else simply a symptom of complete exhaustion. The dirty damned mess of the real lurking behind every image, and holding up every image of thought.

Hélène Frichot is Professor of Architecture and Philosophy, and Director of the Bachelor of Design, Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, University of Melbourne, Australia. Recent publications include Creative Ecologies: Theorizing the Practice of Architecture (Bloomsbury 2018), and with Isabelle Doucet, a special edition of ATR (Architectural Theory Review), Resist, Reclaim, Speculate: Situated Perspectives on Architecture and the City, 2018.

1 Reinhold Martin, “Critical of What? Toward a Utopian Realism” in Harvard Design Magazine (No. 22, Spring/Summer 2005).

2 See Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press. 2003), on Sylvan Tomkin’s study of the volatile affect of shame. Sedgwick notably discusses Tomkin’s shame in relation to what she suggests is theory as a kind of “consensus formation.” (95).

3 Martin, ‘Critical of What?’, 2.

4 See Michael Speaks, ‘Which Way Avant Garde’, in Assemblage, no. 41 (April 2000), and Sarah Whiting, and Robert E. Somol, guest eds.,“OK, Here’s the Plan” in Log, vol. 5 (2005): 5-7.

5 Martin, “Critical of What?’, and George Baird, “Criticality and its Discontents” in Harvard Design Magazine, No. 21, Fall/Winter 2004/2005.

6 Deleuze and Guattari, What is Philosophy? (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 209.

7 Baird, “Criticality and its Discontents’, 1.

8 Hélène Frichot and Stephen Loo, “Introduction: The Exhaustive and the Exhausted – Deleuze AND Architecture” in Hélène Frichot and Stephen Loo, eds, Deleuze and Architecture (Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press. 2013).

9 This essay was originally composed in 2014, and much has happened in the meantime. For a more recent discussion of what I call the ‘methodology of exhaustion’ see Hélène Frichot, Creative Ecologies: Theorizing the Practice of Architecture (London: Bloomsbury, 2018.) Here you will find some of the same ground covered, but in relation to other concerns.

10 Hélène Frichot, “Gentri-Fiction and our (E)States of Reality: On the Exhaustion of the Image of Thought and the Fatigued Image of Architecture”, in Nadir Lahiji (ed.), The Missed Encounter of Radical Philosophy with Architecture (London: Bloomsbury, 2014), and Frichot and Loo “Introduction: The Exhaustive and the Exhausted – Deleuze AND Architecture”.

11 “The Exhausted” was first published not in the collected essays of Critique et Clinique (1993), translated by Daniel W. Smith as Essays Critical and Clinical, where it now appears in English, but first appeared in Samuel Becket’s Quad et autres pieces pour la television (1992).

12 Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There (London: Macmillan, 1980),160-161. Deleuze, The Logic of Sense, trans. Mark Lester, with Charles Stivale (New York: Columbia University Press, 1990), 28-29.

13 Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 378.

14 Deleuze, Essays Critical and Clinical, trans. Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco (London: Verso, 1998), 158.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Deleuze, Essays Critical and Clinical, 160.

18 Ibid, 165.

19 Ibid, 163.

20 Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (London: Athlone Press, 1992), 129.

21 Ibid, 111-22, see also Hélène Frichot, “On Finding Oneself Spinozist: Refuge, Beatitude and the Any-Space-Whatever”, in Charles J. Stivale, Eugene W. Holland, Daniel W. Smith (eds)., Gilles Deleuze: Image and Text (London: Continuum Press, 2009), 247-263.

22 Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 379.

23 Deleuze, Gilles, Difference and Repetition, trans. Paul Patton (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 167.

24 Deleuze, Nietzsche and Philosophy, trans. Hugh Tomlinson (London: Athlone Press, 1983), 130.

25 Deleuze, Essays Critical and Clinical, 169, 179; see also Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (London: Athlone Press, 1989) 166.

26 Deleuze, Cinema 2, 169.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid, 163.

29 See Frichot, “Gentri-Fiction and our (E)States of Reality”.

30 Deleuze, Cinema 2, 165.

31 See also Suzanne Hême de Lacotte, “Iconoclasm of Gilles Deleuze: Deleuze, The Image, the Cinema, the Image of Thought” trans. Patrick Guy Desjardins, in Trahir (December 2010), 1-12.

Hême de Lacotte, Suzanne (2010) “Iconoclasm of Gilles Deleuze: Deleuze, The Image, the Cinema, the Image of Thought” trans. Patrick Guy Desjardins, in Trahir, December, 1-12.

32 Deleuze, Essays Critical and Clinical, 153.

33 Deleuze, The Logic of Sense, 149.

34 Deleuze, Gilles (1992) Cinema 1, 114.

35 Gilles Deleuze, “The Exhausted” trans Daniel W. Smith and Michael A, Greco, in Essays Critical and Clinical (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998) 158.

36 Deleuze, Essays Critical and Clinical, 153.

37 Ibid, 169.

38 Ibid, 154.

39 Ibid, 154.

40 Ibid, 154.

41 Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet, Dialogues II, trans by Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002,) 9, 10, 57 and 59.

42 The Snowdon controversy, where Edward Snowdon, previously an employee of the CIA and also a former contractor for the NSA, released documents proving the existence of not one, but a great number of global surveillance programs, revealing how software and data mining processes had been both developed and put to use, enabled the capturing of content from social networking sites and even private webcam imagery. Snowdon was concerned that an “architecture of oppression” was being constructed through the surveillance of data. See, for instance, Charles Savage and Mark Mazzetti, “Cryptic Overtures and a Clandestine Meeting Gave Birth to a Blockbuster Story”, The New York Times, 10 June 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/11/us/how-edward-j-snowden-orchestrated-a-blockbuster-story.html?hp&_r=0 Accessed 24 April 2014.

43 Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 376.

44 Claire Colebrook, ‘Noology’ in Adrian Parr (ed.). The Deleuze Dictionary (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), 193-194.

45 Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, 376.

46 Deleuze, Essays Critical and Clinical, 159.

47 Deleuze and Guattari, What is Philosophy?, 201.

48 Maurizio Lazzarato, ”Immaterial Labour” in Michael Hardt and Paulo Virno, eds, Radical Thought in Italy: A Potential Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1996) 133-147, 133.

49 Hauptman, Deborah and Neidich, Warren (eds.), Cognitive Architecture: From Biopolitics to Noopolitics: Architecture & Mind in the Age of Communication and Information (Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 2010), 12.

50 Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on Control Societies” in Negotiations (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995) 177-182.

51 Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman (Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2013), 2.

52 Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, 1994, 139.

53 Peter Osborne, “The postconceptual condition, or the cultural logic of high capitalism today” in Radical Philosophy, Vol. 184 (March/April 2014), 19-27.

54 Jakob von Uexküll, “A Stroll through the Worlds of Animals and Men” in Claire H. Schiller (ed.), Instinctive Behaviour (New York: International Universities Press, 1957), 5-76.

55 See, for instance, Jane Rendell’s essay, “When Site-Writing Becomes Site-Reading or Why Space Matters Through Time”, in Lukas Feireiss (ed.), Space Matters: Exploring Spatial Theory and Practice Today (Vienna: Ambria, 2013), where she includes an open source image of the planet earth as a ‘blue marble’, viewed from a later space flight on 7 December 1972 from the Apollo 17.

56 Sloterdijk situates globalisation as a far older phenomenon, suggesting instead that it was when the earth was first circumnavigated and the Americas discovered that there was a conceptual shift of understanding that first displaced the idea of the celestial sphere (die Kugel) conceived by the Greeks, with the notion of the globe as an exposed spherical form (der Globus) across which humans can travel on voyages of discovery. The fundamental conceptual shift being effected from an assumption of worldly shelter, to a realisation of global exposure. See Peter Sloterdikj, Sphären II: Globen, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1999).

57 See articles in Frankfurt Allgemeiner Zeitung, 4th and 24th April 2014. I want to thank Rochus Urban Hinkel for alerting me to these news items.

58 Manfred Lindinger, “Wächter im All” in Frankfurt Allgemeiner Zeitung, 4 April 2014. http://www.faz.net/aktuell/gesellschaft/copernicus-satelliten-starten-ins-all-12879739.html Accessed 24 April 2014.