Bauhaus – Fabricating the Future

By Lara Schrijver

‘Will draw for food’ – is this a joke? Or is it a reality?

A small cardboard sheet, that shows the context of architecture in 2015, when the global financial crisis was still rippling through the practice.1 From the perspective of 2021, when the domains of culture and the arts have been completely transformed by the worldwide pandemic, the troubles of architecture seem relatively small. But perhaps there are some insights to be gleaned from architecture, as a discipline that has historically been strongly dependent on economic cycles.

The global financial crisis of 2008 had a widespread impact, which was strongly felt in architecture and the building industry, albeit with some delay.2 The global shift of manufacturing jobs to low-wage countries had already hollowed out many of the industries formerly present in Europe. This is not an equally spread development – some European countries, like the Netherlands, depend more on service industries, less on manufacturing, while others have maintained a stronger industrial base, like Germany. These differences mark out the distinctions between the countries of the European Union. Much of the global crisis was related to the building boom of the early 21st century, and the varying degrees to which this depended on unstable mortgages and derivatives. In Spain for example, property speculation was driven by a projected value that dramatically dropped after the global crisis. The scale of this property development, delicately balanced on the virtual cash flows of speculation, has left an undeniable mark on our environment – and the projects that were put on hold then became equally visible.

A large-scale property development in Spain, indefinitely on hold. (Jon Nazca / Reuters)

In the meantime, architecture rapidly lost the value it was perceived to have as one of the creative industries. After the 2002 publication of Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class, the creative industries became synonymous with economic prosperity, at least in the eyes of policymakers.3 Floating on this giddy inflation of various art and design industries, a triumphant sense of legitimation was espoused for the arts and the various creative disciplines. The late 1990s and early 2000s saw a widespread interest in city-branding such as well-documented with Gehry’s Bilbao Guggenheim, and until 2008, this was accompanied by a relatively strong building boom.

When the financial crisis hit, it may have had a delayed effect on the building industry, but in the Netherlands, the sense of crisis in architecture was quite prominent, as it followed on the heels of nearly twenty years of optimism, perhaps best captured by the moniker ‘SuperDutch’.4 Nevertheless, the architectural services industry is often linked to economic tides, as it is by strongly dependent on patronage. The contested ‘Skyscraper Index’ offers a strong visual representation of the connection between economic crisis and building height.

Visual representation of the skyscraper index. Barry Ritholtz, ‘The Big Picture’, at http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/skyscraper.png

5 While it seems there is little evidence to support the idea that skyscrapers reach a peak height just at the advent of major economic crises, there is a clear impact on architectural commissions deriving from economic crisis, particularly in the public sector. This is not a new insight. The oil crisis of 1973 for example and a more widespread financial crisis prompted the HUD to retract commissions and quite seriously affected many (semi-)social housing projects. Going back further in history, the crash of 1929 had enormous effects on the building industry. As a particular example, Rockefeller Center was built in the wake of the great crisis, beginning in 1930, and was built in the face of recurring financial risks and losses. This itself raises an interesting comparison to the current postwar welfare state in Europe, as the financing of Rockefeller Center was primarily carried by John D. Rockefeller Jr. – his losses were his responsibility, and his profits were largely his own.6 In contrast, welfare-state governments are held accountable for spending public money, which makes it particularly difficult to legitimate public spending on large building projects during an economic recession. John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s vision of an art and cultural center may have been a risky one, but did prove to bring long-term profit and benefit.

Crisis and Legitimacy

Although architecture and the building industries were certainly affected by the 2008 financial crisis, there is a broader underlying issue of interest here: the self-perception of the discipline and its capacity for innovation in response to crisis. In a seminal article of the 1970s, Robert Gutman examined the nature of architecture as a profession.7 He noted that architecture is in essence an entrepreneurial profession, in the sense that it is service-driven and client-seeking. It nevertheless maintains an air of autonomy more typical of the arts and the cultural professions. As such, architecture typically seeks its legitimation beyond the economic, even as the discipline shows exaggerated responses to economic shifts.

A century ago, one particular moment of economic crisis provided a noteworthy example of a strong innovation-driven response in its wake. The Bauhaus, founded in 1919, grounded in precisely the issues of legitimacy that Gutman would later see as central to the discipline’s self-perception, would in retrospect have an influence far exceeding its short actual existence as a school, which lasted only 14 years. However, as the teachers of the Bauhaus brought their innovative curricula to various schools, its legacy was both stabilized and transformed.

In the Netherlands, and to a somewhat lesser degree elsewhere in Europe, the 2008 crisis had great effects. As architecture was increasingly positioned as part of the creative industries and as economic drive, its perceived contribution to the urban economy resulted in increasing competition between cities in terms of architectural production. Yet this process collapsed in areas most hit by the crisis (particularly in continental Europe), and architects faced increasing difficulties acquiring public commissions after 2010. In response, many architects turned to alternate modes of practice and broader professional networks. From ephemeral experiences such as DUS architect’s BuckyBar of 2010 to brief architectural consultations for 5 cents, architects spent time rethinking what it is that they do.

DUS Architects and Studio for Unsolicited Architecture, The Bucky Bar (2010). A temporary bar inspired by Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes, constructed out of red umbrellas

John Morefield, stand at farmer’s market for architecture consultations (Seattle, 2009)

And this is a valuable response. In fact, in the larger global condition sketched out here, there is a need for rethinking the position of the architect, the tools of architecture and the societal role of the discipline. However, as the impact of our built environment is so great – and simultaneously so limited – I believe that this need for a re-evaluation extends beyond ephemera, experiences or an advisory role. Looking at interventions that focus on the architect as facilitator, game-manager, or other forms of advisory roles in various guises, one might almost think that in the face of the failure of recent iconic architecture to truly intervene, the faith in architecture’s own language has been lost. In this context, I propose that the history of the Bauhaus has a number of lessons for today. Arising in a similar context of economic crisis – perhaps a little less global than today, but in the context of the early twentieth century it may have been perceived as global – the Bauhaus at its founding was deeply connected to industry and crafts, and perceived the discipline of architecture as a driving force in improving living conditions.

Of course, today’s issues are not the same as in 1919. Today, the architect is rapidly being replaced by project managers, contractors, ready-made floorplans and graphic designers. Architects with iconic reputations or sizable and reputable firms are still invited to produce spectacular architecture in countries like Dubai, but the large-scale welfare state project of the European continent is dwindling. Yet there are also similarities that beg some questions. Today, much like the early twentieth-century, transformations in technology are necessitating a review of existing work structures. Where the industrial revolution instigated a turn to machine technologies – also at the heart of the Bauhaus, we are seeing in the digital revolution that remarkable transformations are also taking place that appear to supersede the spatial logic of architecture. Yet these are also speculative assumptions. The simple conditions are the rapid development of technologies, and the responses of a discipline often working in a slow regime of habits, crafts and building traditions.

What then is the core of the discipline, if it is not to be found in iconic architecture, or in the cheerful pragmatism of the SuperDutch generation? And if we are prepared to acknowledge that what is built remains present for much longer than the lifespan of a single crisis, a single generation, or indeed, a single political regime, then how should we approach the value of architecture, if it is also built under a particular logic of economy, power or politics?

Bauhaus Pedagogy from Vorkurs to Workshop

Significantly, at the founding of the Bauhaus in 1919, there was a perception of architecture as not ‘pure’ – in contrast to particular art forms, architecture was related to the craftsmanship of the carpenter, and also to industrial production. This derived from its roots in the Academy of Arts in Weimar, where Henry van de Velde was director until 1918. With Van de Velde, it became informed by the logic of the Arts and Crafts movement. After Gropius became director, he merged the academy with the Kunstgewerbeschule, and introduced a stronger presence of industrialization and contemporary forms of production. With its move to Dessau in 1925, the connection to existing industrial production techniques became paramount to the envisioned future of the school. While the founding statement from 1919 clearly retains the sweeping statements that characterize the discipline’s search for legitimacy, there is also a striking appeal to the importance of craftsmanship and its material knowledge. In Weimar, the curriculum tended more towards an embodied knowledge based in craftsmanship, while the Dessau curriculum began to focus more on the integrative nature of architecture as a discipline, on the design thinking that lay at its core.

As such, Gropius founded the Bauhaus on the existing ideas of the Kunstgewerbeschule, projecting a full modernization of the discipline, from the very foundations of the educational curriculum).

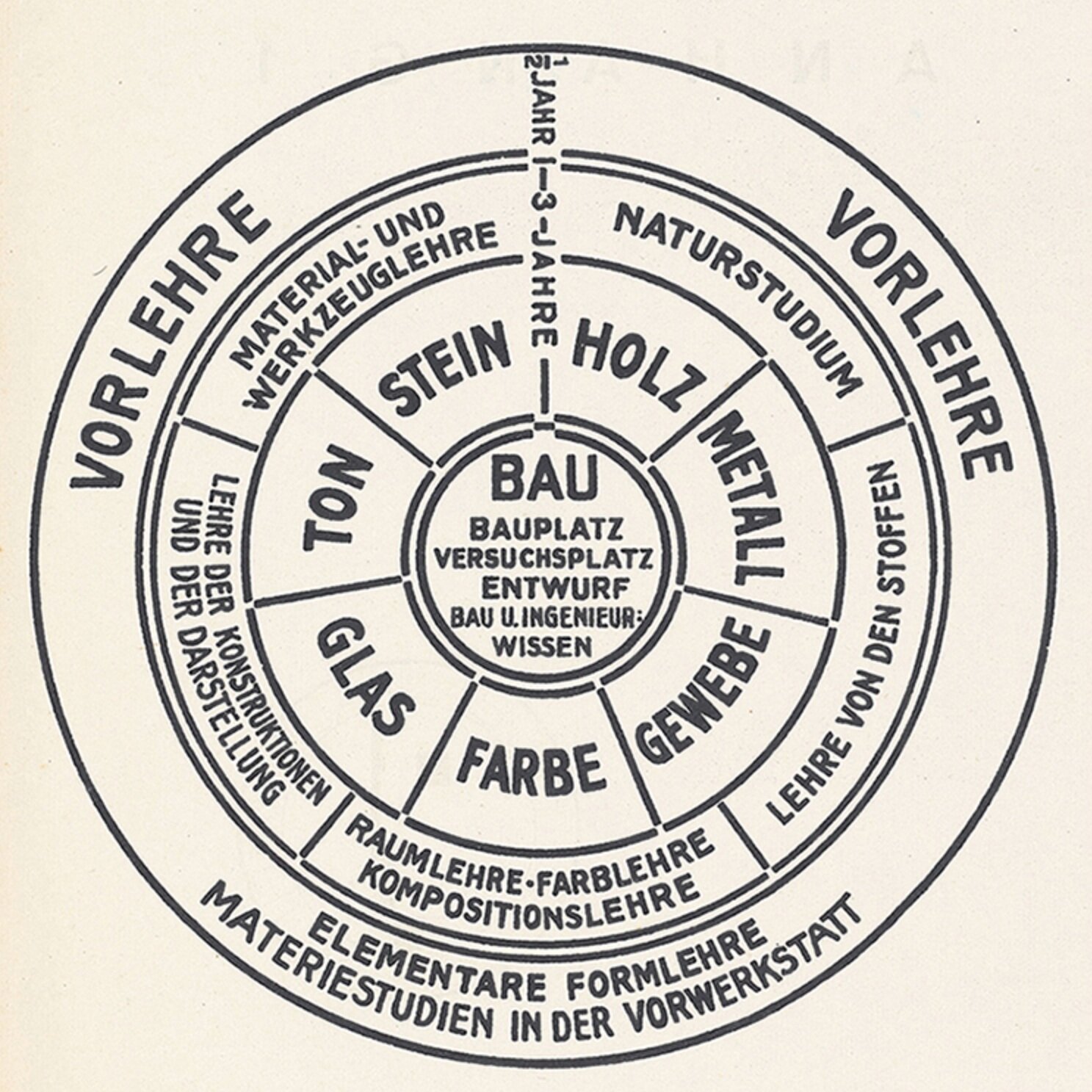

Walter Gropius, Bauhaus teaching program

The evolution of the curriculum is in itself a complex history, with the diagram becoming central after the school was founded, and in essence also projecting a desired future rather than the actual state of the curriculum at the time.8 However, one might argue that the most crucial features of the Bauhaus curriculum are adequately represented in the diagram. From outside to in, the ‘elemental studies’ were situated in the Vorkurs, which revolved around a heightened perception and sensitization to color, form, materials, and other elemental features of architecture and art. In the middle, the final aim was to attain the ability to build. The Bauhaus was defined not by a conceptual curriculum aimed at the transfer of existing knowledge, but rather by the embodiment of knowledge, and by the opportunity to do things, to try things out. The workshop as such must not be underestimated. Throughout the curriculum, its theory was interwoven with the physical, manual, experiential understanding of what was being taught. In addition, the structure of the Vorkurs, in which central components of design skills were trained, both as a craft and as a concept, were foundational in training students in skills and abilities, while at the same time introducing the critical eye and a reflective practice. The Vorkurs, put together by Johannes Itten as an introductory curriculum intent on building up the component abilities of design, included an intensive training in particular skills of drawing and design, such as color studies and contrast studies. This formative structure then enabled students to utilize these skills in the synthesis-oriented workshops that followed in the later years.

And perhaps it is the Vorkurs that has the most to teach us for today. More than anything, it consisted of a heightened sensitization to space, texture, material, color. It is built on the notion that one does not just conceive of a design, but feels it. In essence, the manner in which Itten felt the inner creativity of the students was best released, was precisely a very concentrated focus on the embodiment of their experience and knowledge. Although the spiritual focus of Itten was strong, it is also this understanding of the mutual influence of the senses that informs much of his work. Moreover, he treated his guidance as a mode of facilitating the particular qualities of students, rather than conveying a static body of knowledge. “Rhythmic drawings involved an awareness of kinesthetic feelings, as did exercises like arm-swinging, aimed at developing a deeper understanding of circular forms. Such interrelationships among the sense faculties, in this case muscular as well as visual, were further explored in exercises using a wide variety of material textures, offering both optical and tactile sensations.”9

The craft-based curriculum was seen as a way of attaining a more creative, organized, structure, and indeed even spiritual understanding of and ability to design. It was, one might say, a way of life rather than a school, as is immediately evident in the many photographs showing youthful conviction and absolute engagement.

Morning exercises at Itten College in Berlin, 1930

The conviction of Gropius himself that there is no essential distinction between the artist and the craftsman is present throughout the curriculum. And he notes in the founding manifesto that the final aim of all visual activity is building. This deep-seated conviction harks back to an earlier era in which architecture was always indisputably the mother of the arts.

While the Bauhaus is often seen as one of the key protagonists in the widespread dissemination of modern principles, modern dwellings, perhaps its most crucial contribution was to understand the tacit dimension of architectural design. The powerful social role our built environment may have is founded upon values embedded in our objects, which in turn influence us. If the space is designed in a cohesive, ‘designerly’ way, perhaps this contributes to precisely that notion of transcendence that we seek in our cultural production. This is the line that we can draw throughout history – the significant project and their influences are often founded not simply on an ideological position but on a notion of skill, quality, value, and other less definable, yet tangible traits.

In fact, it is notable how the logic of the Internet and the do-it-yourself mentality of today strike a chord with the principles of the Bauhaus. On the Internet, many instructions are to be found for improving one’s neighborhood irrigation system, or how to build your own house.

Van Bo le Mentzel, ‘Build more, buy less.’

The desire for a customized product seems at odds with how we now perceive the Bauhaus, which provided a significant impetus for mass production. Yet it eminently suits the principles of the workshop, which contain an implicit recall of the social and educational values attributed to architecture in the earlier Arts and Crafts movement.

Craftsmanship, Technology and Embodied Knowledge

Of course, in an age that allows people to draw their own floor plans and arrange their own kitchens at the flick of a mouse button, one might do well to ask why we should turn to such teachers as Itten who required a physical and spiritual understanding of textures and colors. I would argue that this is in fact crucial. Not necessarily to refuse the presence of a computer within architecture school, but rather to develop a heightened sensitivity to the environment and the elements of building, in order to be able to work with these elements more fluidly and confidently within the discipline of architecture. As such, it engages the multiple levels of sensorial perception of our environment. Much as we might be tempted to orient our architecture curricula fully around the newest technologies, the Bauhaus curriculum shows a potent combination of new technologies and individual expertise, honed and trained by extensive attention to not only the visual but also the tactile and the aural dimensions. More than anything, it is the legacy of the workshop and the experience of materials that we might turn to today to revisit some central concerns in architecture. In a time when our resources are dwindling and our requirements of our built environment increasing, we may do well to found the future of the discipline on a well-developed sense of the material reality of the built environment. Fostering the spirit of experimentation not only develops abstract creativity, but presents the consequences of design decisions in undeniable material form.

So how might this help us in a highly technological era, one defined by ephemera, social media and by spectacle? Are we not equipping our students best by teaching them technological skills such as computer programming and scripting, allowing them to flexibly apply these skills? Is a Vorkurs consisting of Grasshopper, web design and BIM not more effective than old-fashioned courses in sketching? I would rather suggest that the fundamental elements of the Bauhaus pedagogy offer a richer approach to contemporary design precisely because of the interaction between its elemental features and the overall synthesis of design thinking.

This involves the particular key features already noted in relation to the Vorkurs and the workshop: sensitization, embodiment and synthesis. Feeling textures, looking carefully, distinguishing materials not only visually but by touch are central to the Vorkurs both as structured by Itten and later modified by Albers.10 Although this individuated sensitization became less prominent under the later direction of Hannes Meyer, it marked one of the most distinctive features of the Bauhaus, particularly in relation to its acceptance of modern industrial fabrication. Of course, this focus on sensitization implies the embodiment of knowledge. If the skills of the architect could be sufficiently trained by conceptual understanding, there would be less of a need for slow and concentrated perception. At the time, it was simply incorporated into the curriculum, but it was also distinctly identified within the domain of psychology: ‘The motor sense aims in the right direction. That’s a matter of feeling, not of seeing. You don’t watch what the arm does, no! You go by the feeling with the arm.’11 These ideas were perhaps more present in early-twentieth-century philosophies that questioned the adequacy of quantified scientific knowledge, such as the work of Bergson, and of Merleau-Ponty. These, as a number of their peers, sought to describe and understand a form of knowledge that one can only apprehend in action, in doing, sensing, or making. Finally, the Bauhaus curricular structure that aims at the Versuchplatz and the Bauplatz is aimed at connecting or situating these particular elements in larger frameworks or networks of knowledge.

In this sense, they intuited something far before neuroscience had the ability to prove it: the mutual influence between body and mind are far greater than is often assumed. So while it may be inevitable to teach our students computer skills, the specific learning trajectory set out by feeling materials, working with elemental aspects of building, and by a heightened sensitivity to the components of architecture may well unlock an insight otherwise unattainable.

In 2012, I was part of an experiment where the actual fabrication process is part and parcel of not only the design work, but also the understanding that derives from it. In 2012, the ArtEZ Academy of Architecture organized a week-long studio workshop, for which Ralph Brodrück led a group of students in a welding project.12 I was invited to provide a theoretical counterpoint to the work they would be doing. The original workshop proposal was based on a division of labor, with theory as a separate component. I was meant to discuss notions from Richard Sennett’s The Craftsman alongside the practical work led by Brodrück, which was aimed at designing and building a steel construction capable of keeping chairs aloft at a height of three meters.

Plein 12, workshop on Sennett and steel, led by Ralph Brodrück, TU Eindhoven, and Lara Schrijver, TU Delft

Rather than this division, in which Brodrück would teach the students to weld and coach them in their designs, and I would read with them, we found that a hybrid approach worked much more efficiently. I was more easily able to explain what Sennett was referring to in terms of ‘material resistance’ and its influence on thinking and the intellect, when accompanying the students in the process of learning to weld. The very difficulty of feeling the precise moment of arc welding was a far better illustration of an abstract idea such as ‘the intelligent hand’ than any description I could have offered. Likewise, it seemed that the students were more critical and thorough in their design production precisely because of the ideas we were discussing as their work progressed.

In the end, the students remarked that the greatest learning curve for them was to integrate their design ideas with the limitations of the material and their welding skills. Their insight grew exponentially with the process of ‘putting things together’. Even with the fantastic technologies available today, with renderings growing out of envisioned floorplans, there is little surrogate for hands-on, direct, embodied experience.

As we look back on the remarkable history of the Bauhaus, it is striking how influential its ideas were. The mere 14 years of the school’s existence have continued to inform many other curricula in its wake. In part, this may be attributed to the circumstance of emigration in the years of World War II – many of those involved in the Bauhaus chose or were forced to find new occupation elsewhere. The massive migration of these ideas has proven influential throughout many schools in the United States, and many ideas were later reintroduced in postwar Europe. However, I also propose that it is more than mere circumstance that founds this influence. I propose that the foundation of the Bauhaus and its curriculum touched a particular strain of thinking that is not only attractive to those students who think through their craft, but that is also extremely powerful today. As the world becomes increasingly abstract and ephemeral, we have need of understanding what it is that we do. As such, it is the fundamentally craft-based ideas of design thinking – those types of thinking that cannot be fulfilled without actually getting one’s hands ‘dirty’ – without trying things out – are a line that might offer hope for not only the field but also for current research.

In point of fact, those technologies that are looming on the horizon as a threat to employment are precisely the same technologies that are facilitating self-build projects and the sharing economy. As such, our school curricula seem in need of a training in experiment, in order to ensure that our students are equipped for a time of flux and rapid shifts. The Bauhaus curriculum appears particularly strong in sensitization, and in strengthening awareness. While heightened capacities of observation may not be the immediately obvious skill to train in relation to rapid film sequencing or computer renderings, they do add precisely that element that may easily slip under the radar in computer-generated imagery. Indeed, one could envision a more embodied understanding of technology as precisely a 21st-century iteration of what Henry van de Velde meant when he spoke of making ‘art as appropriate to industrial fabrication’. For today, as some focus on the inevitability of progress, and others call out to restrain our technologies, there are many other concerns touching the discipline of architecture. Indeed, the expanse of global activity and our knowledge of projects in places far away, have perhaps changed our perception of the discipline. At the same time, as it rises into cosmopolitan action, the discipline of architecture is eminently tied to the place it is produced. Somewhere in between this cutting edge of innovation, and the stable, incremental development of artisanal knowledge, lies a rich domain of everyday practice, of tolerant normality, of adaptation to some technologies and rejection of others.

Lara Schrijver is professor of architecture in theory in the Faculty of Design Sciences at the University of Antwerp. She was previously affiliated with the TU Delft and the Rotterdam Academy of Architecture. From 2016 to 2019 she was co-editor of the annual review Architecture in the Netherlands.

_________________________________________

1 This article was originally written in 2015, when the effects of the global financial crisis of 2008 were still clearly visible in architecture, particularly in the Netherlands. While a number of these effects has by now subsided, the general insights and adaptations still hold.

2 For example, in 2010, Reinier de Graaf of AMO/OMA curated an exhibition titled ‘On Hold’, which showed a series of global building projects that had been postponed indefinitely by their clients. Reinier de Graaf, On Hold, exhibition catalogue (Rome: The British School at Rome, 2010). According to the Dutch Architects Association (BNA), the profession was hardest hit in 2013, after running commissions had been completed, and before new commissions were extended. BNA Annual report 2013 (https://issuu.com/bna_publicaties/docs/bna_jaaroverzicht-2013-hr-losbladig). The conditions in the United States of America were notably bleak in 2012, see Vanessa Quirk, ‘After the Meltdown: Where does Architecture go from here?’ 17 Apr 2012. ArchDaily. Accessed 02 Oct 2014. www.archdaily.com/?p=226248

3 In the Netherlands, Robert Kloosterman has documented and analyzed the marked increase in employment in the culture industries since the mid-1990s. Robert Kloosterman, ‘Recent Employment Trends in the Cultural Industries in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague and Utrecht: A first exploration’, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, Vol. 95, No. 2 (2004), 243–252. Florida has since questioned his own conclusions: Sam Wetherell, ‘Richard Florida Is Sorry’, Jacobin 19 August 2017 (https://jacobinmag.com/2017/08/new-urban-crisis-review-richard-florida).

4 Bart Lootsma, SuperDutch: New Architecture in the Netherlands (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2000).

5 While many agree that there is no robust correlation between crisis and building height, studies have found other robust correlations based on per-capita income. Jason Barr, Bruce Mizrach and Kusum Mundra, ‘Skyscraper Height and the Business Cycle: Separating Myth from Reality’ (July 1, 2014). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1970059 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1970059

6 For a history of the construction of Rockefeller Center, particularly with its financing troubles, see David Loth, The City within a City: The Romance of Rockefeller Center (New York: Morrow, 1966).

7 Robert Gutman, ‘Architecture: The Entrepreneurial Profession’, Progressive Architecture 58, no.5 (May 1977), 55-58.

8 For various interesting insights in the founding ideas of the Bauhaus and the reality that accompanied it, see Zeynep Çelik Alexander, ‘The Core that Wasn’t’, Harvard Design Magazine 35, 2012, 84-89; Jean-Louis Cohen, The Future of Architecture. Since 1889 (London: Phaidon, 2012), 153-156.

9 Clark V. Poling, ‘Design and Form: The Basic Course at the Bauhaus by Johannes Itten’, review, Art Journal vol. 36 no.4, 368-370.

10 An excellent overview of the qualities of Albers’ teaching in relation to embodied knowledge is given by Eeva-Liisa Pelkonen, ‘Interacting with Albers’, AA Files 67, 2013, 119-129.

11 Erwin Straus, as quoted by Eeva Liisa Pelkonen, ‘Interacting with Albers’, AA Files 67, 2013, 119-129, 123.

12 Plein 12. The workshop was organized by the Academy of Architecture in Arnhem, conceived by Wim Nijenhuis, and included four different workshops on particular expressions of craftsmanship. Plein 12, ArtEZ Arnhem, 2012.