Space, Power, Control

By Sven-Olov Wallenstein

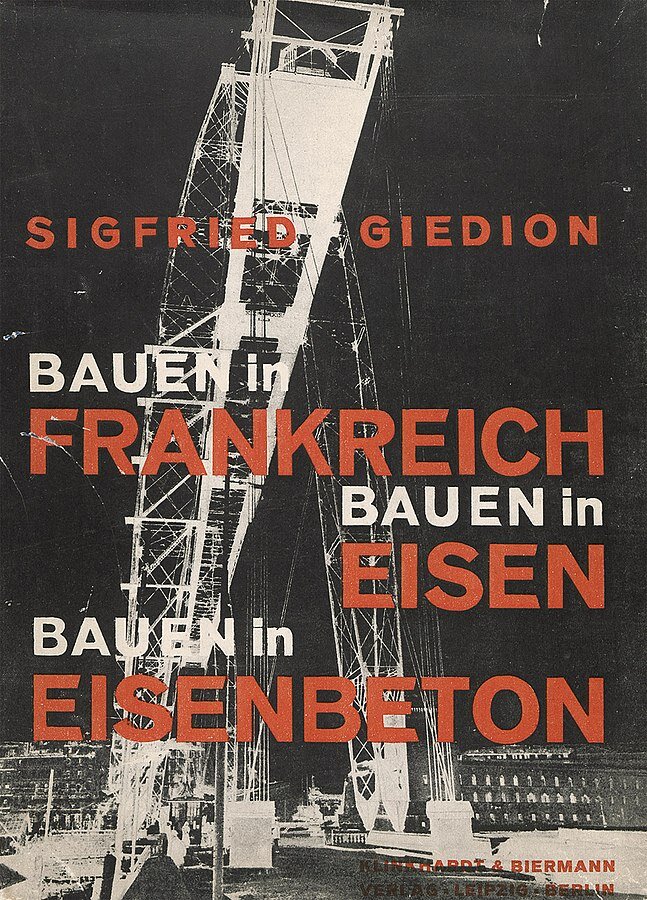

Sigfried Giedion’s Bauen in Frankreich (1928)1 is one of those books that posterity has come to rediscover as a decisive text in early modernist architectural theory, even though it received little attention in its own time. The book projects a dazzling view of the new industrial architecture, and it is itself one of the period’s most effective visual-rhetorical constructions, in which the graphic design of Moholy-Nagy juxtaposes Giedion’s forceful and prophetic statements to images of the new machine technology in order to convey a sense of an irresistible modernity. But it also takes us right into the heart of the philosophical claims of the modern movement by proposing a radical interpretation of space that brings together motifs from a discussion underway since the latter third of the nineteenth century, and by projecting a new view of the organic and the technological. In this it also draws out a set of consequences for social space that Giedion’s subsequent and more “official” work, Space, Time and Architecture (1941), will retract in order to mitigate any “avant-gardist” conclusions, above concerning the very existence of “architecture” itself.

Construction and Interpenetration

The essential contribution of the nineteenth century, Giedion claims, was the grand scale glass and iron constructions and the use of reinforced concrete that would revolutionize the building trade. In the vocabulary established during this period, which expresses a particular unease and a sense of an impending crisis of form, these innovations could be seen as still relating to the “core-form,” whereas their consequences for the “art-form” were still in the balance,2 or, as Giedion writes, part of architecture’s “subconsciousness”: “Construction in the nineteenth century plays the role of the subconscious (des Unterbewusstseins). Outwardly, construction still boasts the old pathos; underneath, concealed behind facades, the basis of our present existence is taking shape.”3 Giedion sketches a long morphological development beginning already in the late eighteenth century, which however was blocked by a traditionalist and eclectic interpretation of architecture—thus pushing the progressive moment down into the “subconscious”—and covered over by a discourse on “styles.” This tradition, he proposes, can now regain momentum, first because of the breakthroughs in architects like Auguste Perrier and Tony Garnier, which then achieved a first degree of perfection in Le Corbusier. The “constructive subconscious” that secretly guided the former century beyond the confused dialectics of style can now become rational construction, bringing the different layers of history together in a synchronous whole.

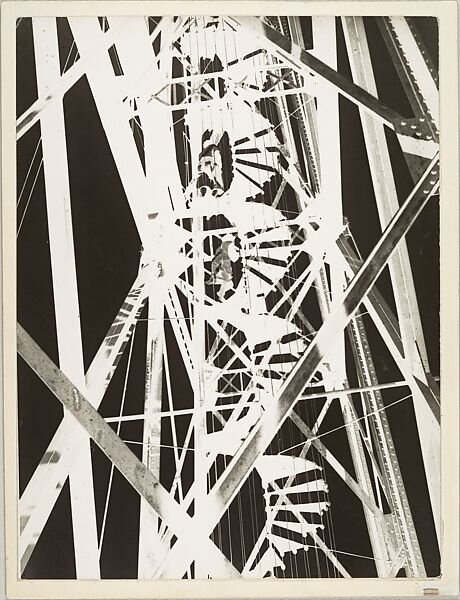

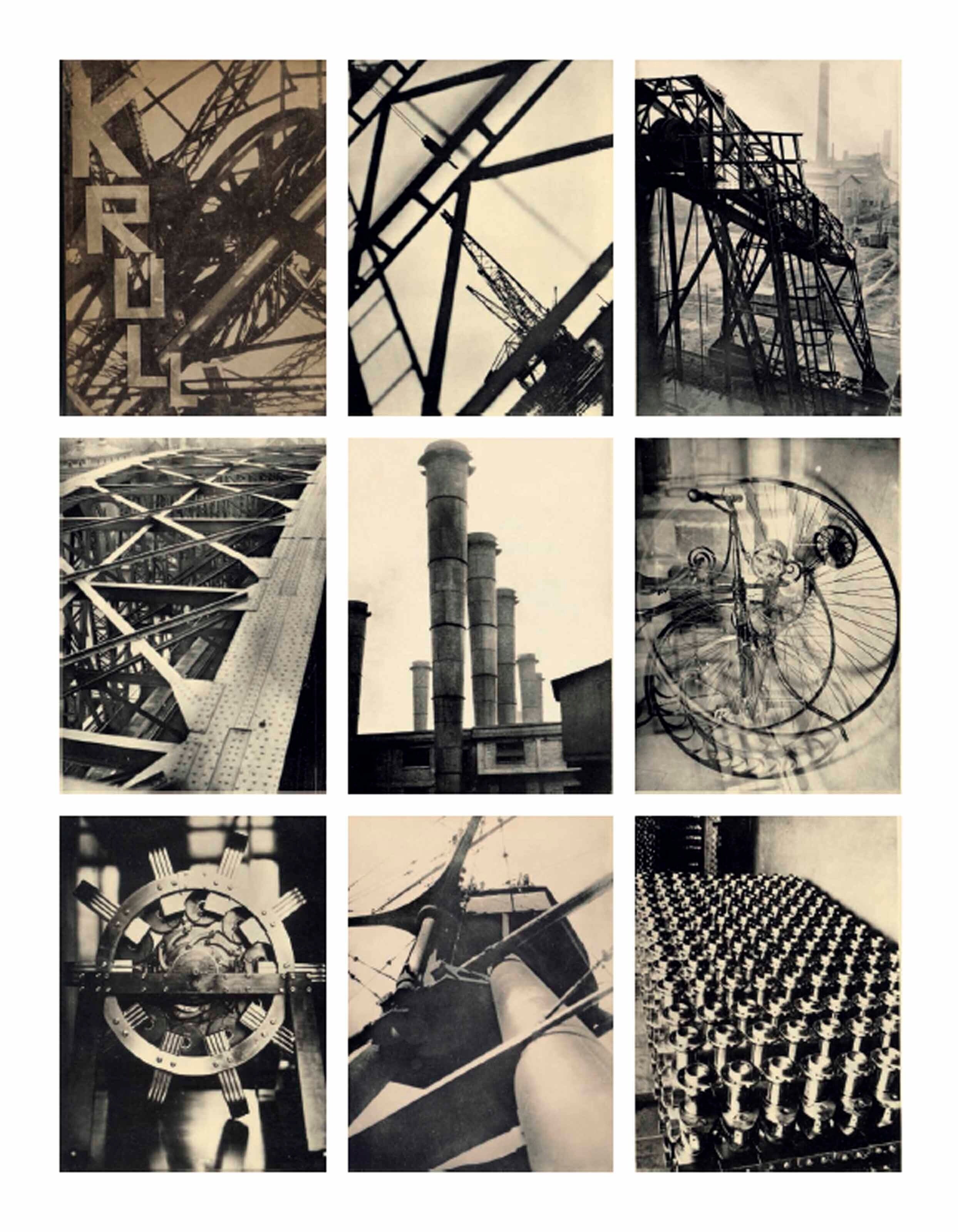

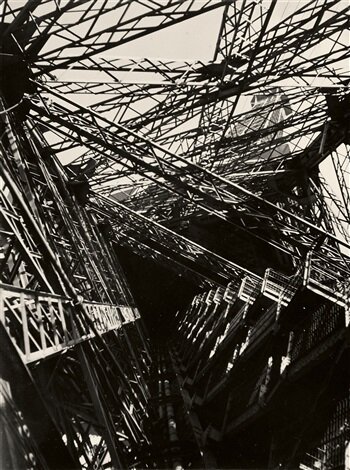

Lószló Moholy-Nagy, Pont Transbordeur, Marseille, 1929 / Germaine Krull, Métal (Paris: Librairie des Arts Décoratifs, 1927-28) Germaine Krull, La Tour Eiffel, 1928

The examples cited are drawn to a great degree from modern engineering, the Eiffel Tower and the Pont Transbordeur in the harbor of Marseille,4 to Gropius’ Bauhaus building in Dessau. As we have noted, the paradigmatic example is however Le Corbusier, who becomes the object of long and lyrical descriptions. In Corbusier’s apartment buildings in Pessac, Giedion writes, “neither space nor plastic form counts, only RELATION and INTERPENETRATION. There is only a single and indivisible space,” and the light-weight and slender wall elements that had been criticized for resembling sheets of paper to him rather appear like “Cubist paintings, in which things are seen in a floating transparency,” producing a “dematerialization of solid demarcation that distinguishes neither rise nor fall and that gradually produces the feeling of walking in the clouds.”5

Giedion’s more general and speculative proposal, beyond the appreciation of the aesthetic perfection of singular works, is that the division between subject and object, and between the organic and the technological, is undergoing a fundamental change. In the modern world, he suggests, individual things will be dissolved into a single, intense, and malleable space, where mind and machine are absorbed into a new kind of spatial unity that he terms “interpenetration” (Durchdringung).6 The concept of interpenetration used to bind all these cases together first involves a set of architectural parameters: spatial volumes that intrude upon each other, levels that are made to communicate by the partial removal of floors, osmotic relations between interior and exterior, buildings composed of several intersecting volumes that create a fluid whole. This space of interpenetration, however, is not exclusively realized in architectural inventions or technological achievements, it also signals, through the changes that it effects in consciousness, a political shift toward a space of communality, a being-together of subjects and objects as well as of classes and social groups; it is an emancipation that heralds a collective order, while at the same time providing architecture with a decisive yet diffuse role in the creation of this order.

The leveling of compositional and tectonic hierarchies, as it extends along a continuum from the single building to the city—eventually depriving these two poles of the their absolute status, if not rendering them obsolete—corresponds to a leveling of social divisions between forms of labor and social classes. A common task begins to emerge, Giedion suggests, although it requires that we discard traditional ideas of architecture as a bearer of merely aesthetic and formal values if we are to perceive the true stakes. This incipient space is indissolubly at once architectural, perceptual, and social, and in drawing together the subjective and the objective, the social and the aesthetic, it prepares and promises a new form of life.

Space thus no longer appears as an empty, neutral container for things or as a set of abstract coordinates, but rather as a field of transformation, traversed by forces—it is, we might say, using a term forged much later by Deleuze and Guattari, a smooth space made up of virtual relations, rather than an already striated geometric space into which entities would be inserted—and architecture faces a new task: no longer to produce self-sufficient forms that symbolize, represent, or even express something that would precede them, but rather to create specific conduits for a stream of life that flows through them and to enhance its potential; to striate the smooth, so as to extract a surplus value for form out of what otherwise would remain a threatening formlessness.

The new conception of space would then be both the result of construction and the element in which it unfolds, a product and a precondition, an invention and a discovery. If Giedion provides us with an account of the genealogy of core-forms, he however seems oblivious to the shorter legacy of predecessors when it comes to the question of space as a foundational category. With this question, we enter into one of the most decisive prehistories of modernist architectural theory, which still reverberates in many discourses that would claim to either disown or pursue the modernist legacy.

Empathy and Space

The discourse of space as an explicit category in aesthetic theory has a short but dense history, and it can be traced back to the turn towards new psycho-physic theories that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century, and then to the discussions of “empathy” (Einfühlung) from the 1870s, as they developed from the pioneering work of Robert Vischer, through Adolf Hildebrand and Heinrich Wölfflin, up to the first explicit claims for space as the founding idea of architecture made by August Schmarsow in the 1890s.7 Drawing on the legacy of Kant’s transcendental turn—in which space and time were reinterpreted as forms of intuition and thus as conditions of possibility for knowledge rather than as features of the things themselves—but filtering it through a new experimental science that aspired to displace traditional philosophy, categories and forms of intuition were here understood on the basis of scientific data. Superficially, this may be seen simply as a curious and easily refutable misunderstanding of Kant’s project, but more productively it can be interpreted as part of a gradual transformation of the very idea of the a priori into what, following Foucault’s analysis of the epistemic formation of this period, could be called objective transcendentals, in which the contents of knowledge are made to function as transcendental reflection: they are both empirical givens and the conditions for any empirical givenness as such.8 These data were mostly drawn from psychology, although history and the emerging social sciences also made their respective contributions, resulting in the emergence of the kind of psychologism or historicism against which the two major new movements at the turn of the century would subsequently react, analytic philosophy with Frege and phenomenology with Husserl. While the anti-psychologistic gesture of Husserl was instrumental in bringing about the renewal of transcendental philosophy (whereas Frege’s analysis of thoughts as entities separate from the mind eventually gave rise to the linguistic turn), the sharp divide it at first seemed to set up against its own immediate past was misleading, and the dynamic and genetic dimension of the subject soon returned in phenomenology, which indicates the extent to which it was never a question of simply returning to Kantian a priori structures. Husserl’s true problem was rather that of a dynamic transformation of the transcendental for which the preceding investigations into the psychological genesis of knowledge could neither be ignored nor simply assumed as factual answers to the problem of epistemology, but instead called for a different type of founding. In aesthetics, the attempt to reground the discipline through a rapprochement with the new forms of psychology and psycho-physiology had already been particularly fertile, and it is this line of thought that can be followed up in relation to the statements of Giedion, who unwittingly synthesized a whole gamut of theories and discourses.

The historically decisive formulations of this new field of inquiry can be found in Gustav Fechner, who advocates the shift in the most general terms: aesthetics, in order to finally become a science, must be developed from below (von unten), starting in empirical observations, and not from above (von oben), as in the idealist tradition from Schelling and Hegel.9 We should not analyze abstract ideas of art and beauty, Fechner suggests, but investigate our actual experiences, and aesthetics in this version becomes an experimental psychology that seeks the laws governing psychological processes, which in turn are ultimately grounded in physiological states.

The theory of empathy was an attempt to account for this lawfulness, and if we bracket the earlier discussions of the term in Schleiermacher, whose main interest was the hermeneutics of historically distant texts, we encounter its first relevant use in the young Robert Vischer’s dissertation, Über das optische Formgefühl: Ein Beitrag zur Ästhetik (1873). Vischer distinguishes between everyday seeing (Sehen) and the specific and focused look (Schauen) that we direct towards artworks, and his question is why, in the latter case, we have a tendency to appreciate certain forms. The answer lies in a transference that occurs spontaneously between the mind and objects, on the basis of our physical interaction with them: in empathy we become part of what we see. For Vischer this ultimately depends on a process of natural identification, an empathic transference that occurs in relation to all things, but attains a higher level in art and the optical sense of form, through which we get access to “a higher physics of nature,”10 with a formula that might have been derived directly from Schelling.

Consequently, empathy is present just as much in the production as in the reception of artworks, and the process of which these two moments are part goes beyond the subject-object divide towards an integral philosophy of nature: empathy works in two ways, and the Ein-fühlung is a “feeling-in” of the subject in the object as well as of the object in the subject.11 Ironically, the demand for empirical science made by Fechner almost immediately reverts to its speculative opposite, although not necessarily as a misunderstanding, but rather as a working out of an inner tension that is constitutive of the new physiological aesthetic as such. When art is brought back into and grounded in the sensorium—a process that had been underway since the initial stages of aesthetics, in Baumgarten’s writings from the first half of the eighteenth century—the sensible, the sphere of aisthesis, does not remain the same, i.e., it is no longer a lower domain subordinated to our higher faculty of reason, to which it merely would deliver material in a raw and unprocessed state, but begins to acquire a relative autonomy that also demands a new and expanded understanding of thought itself. The hierarchy between the sensible and the intelligible is transformed into a fluid exchange, continuing through the ambivalent position of aesthetics in Kant (on the one hand a transcendental aesthetic, with space and time as the sensible elements of pure reason, on the other hand a new dimension of the faculty of judgment that requires a critique of its own), the rapidly shifting theories of philosophy’s grounding in intellectual and aesthetic intuition in Schelling, the fluctuating evaluations of art in Nietzsche, and beyond Nietzsche to a long legacy of twentieth-century thinking on art. Nietzsche’s own treatment is in fact exemplary of these ambivalences, from the early claims in The Birth of Tragedy, where art is determined as the “highest task and the proper metaphysical activity of life,” through his middle period, where he turns to a positivist critique of speculative aesthetics—which echoes in some of his last writings, where aesthetics is mockingly portrayed as “nothing but applied physiology”—to his final period, where art is understood in terms a perspectivism that calls for an entire reevaluation of the sensible, outside of the Platonic hierarchy.12 As these examples show, the trajectory of the aesthetic is anything but a straight and linear development; it sidetracks, backtracks, and follows a sinuous line that nonetheless eventually ushers in an important strand of twentieth-century art theory, where another feature becomes decisive, which was also there from the beginning, albeit relegated to the margins, i.e., that the sensorium is itself something that is produced by technological means.13

Within the nascent theory of empathy, Vischer’s initial intuitions were developed further in Heinrich Wölfflin’s “Prolegomena to a Psychology of Architecture” (1886), which asks the question how pure tectonic forms can be understood as expressive. Here too the human body is taken as the ground, and the physiological aspect is even more pronounced, whereas Vischer largely remained within a more limited optical dimension. It is because of our body that we can understand weight, contraction, pressure, the bearing of loads, etc., which for Wölfflin ultimately stems from of a dynamic inherent in nature itself. Matter strives to descend and to attain a state of formlessness, while the “formative force” pushes towards gathering, elevation, and a higher unity. Forms can thus be taken to develop organically out of matter because of an “immanent will” that wants to “break free,” and while Wölfflin perceives himself as Aristotelian, he seems to be more of a Baroque thinker, and there is an unmistakable Leibnizian inspiration in this idea of “plastic forces.”14 In Wölfflin the concept of space as such, however, tends to recede into the background in favor of the biomorphic drive, and it comes to be understood more in the sense of an environment or an “Umwelt” of an organism that itself remains the center.

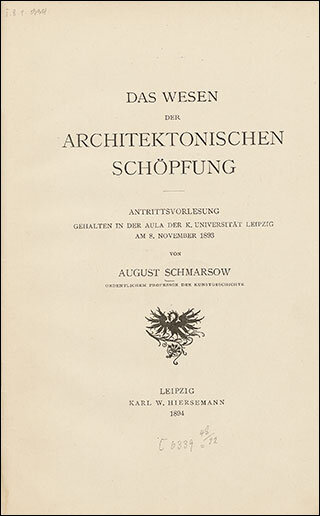

Seven years later the theme is brought to a new level in the work, of Adolf Hildebrand, and then finally by August Schmarsow. Hildebrand’s “The Problem of Form in the Fine Arts” analyzes the perception of sculpture, and for him space is a continuum, like a basin of water where individual bodies form separate volumes. In architecture our relation to space is expressed directly, it becomes present in terms of a “total spatial image” within which all tectonic relations acquire their significance. This conceptual development culminates in Schmarsow’s “The Essence of Architectural Creation” (1893), where the autonomy of the single architectonic elements is even further reduced in favor of a total experience. We cannot understand the work of architecture if it we see it as stones and vaults, Schmarsow claims; instead it relates to a total sense of space originating from our body as a zero-point where the spatial coordinates intersect. Architecture produces a “feeling of space (Raumgefühl), it is a “creatress of space” (Raumgestalterin), and only on this basis can its parts and tectonic details be expressive and have a specific meaning.

The radical conclusion that could be drawn from this is that the body is not simply—primordially speaking not at all even—in space, as if in a container: the objectivity of space is fundamentally a projection, arising from or woven out of the subjectivity of the subject. While these ideas are only germinating in Schmarsow, he anticipates many of the themes that will become central in the phenomenological tradition from Husserl to Heidegger: the reduction of objective Cartesian extension, the analysis of the kinesthetic sphere through which the ego organizes a system of motility and tactility, the difference between the objective-physiological Körper and the living Leib, even the idea of the earth as an ontological ground of the tectonic categories.15 But he also hints at something that would only enter phenomenology in Husserl’s late work, and then in Heidegger, i.e., a historicizing of the ground, in which this foundational space is itself pried open and turned into a techno-corporeal assemblage. The history of architecture, Schmarsow proposes, should be written as the history of the “senses of space,” which also means to write a history of the body, and of the changing character of intimacy and self-relation. Architecture is rooted in an experience of space, which in turn is founded upon the body, but this body is itself subjected to change; it is inscribed in all those technological assemblages that condition our experience of space, so that it becomes a subject-object compound, able to orient itself in the world because it is itself a product of this world.

Illustration on page 236 in Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, von material zu architektur, a facimile of the 1929 edition (Florian Kupferberg, 1968)

Translation of the original caption: “from two photographs (negative) copied onto each other arises the illusion of spatial interpenetration, which perhaps can be experienced in reality only by a later generation--in the form of glass architecture.”

Power and Control

The project of the avant-garde as we find it in Bauen in Frankreich and many other similar texts from the period is one possible outcome of this,16 even though it in the end pushes the claims of Schmarsow far beyond their original meaning. The task becomes to actively produce a new space, to break down the barriers between subjects and objects, humans and things, in order to allow for a new structuring of everyday life from the bottom up, based on the concept of interpenetration. In claiming that architecture is not first and foremost a set of forms and structures placed in a neutral and pre-given spatial container, but a technique for generating space and the experience of the subjects that inhabit it, Giedion is drawing a radical conclusion that was prefigured in at least half a decade of intense research in aesthetic psychology, and taking it to a new level.

This conclusion will in the last instance strike back at the traditional concept of architecture, something Giedion does not fail to notice. If we must abandon the idea of architecture as an art form that produces autonomous and free-standing objects to be judged according to inherited aesthetic and morphological criteria, this means that it must be understood as part of a larger process, a “stream of movement” (Bewegungsstrom) that will require different analytical tools and concepts. “It seems doubtful,” Giedion notes in the beginning of his book, “whether the limited concept of ‘architecture’ will indeed endure. We can hardly answer the question: What belongs to architecture? Where does it begin, where does it end? Fields overlap: walls no longer rigidly define streets. The street has been transformed into a stream of movement. Rail lines and trains, together with the railroad station, form a single whole.”17

Van Nelle factory, 1925-1931, Rotterdam. Architect Leendert van der Vlugt from the Brinkman & Van der Vlugt office in cooperation with civil engineer J.G. Wiebenga.

The idea of a stream, flow, or flux (Strom) might here seem merely metaphorical, but it shows the profound link not only to the tradition of empathy, but also to philosophical ideas of the time, above all Husserl and Bergson, both of which seemed equally oblivious to their recent past. Rather than a container or a Cartesian substance undergoing modifications, for Husserl phenomenological consciousness is a “stream of experiences” (Erlebnisstrom) held together by its inherent temporal structure of retentions and protentions, just as Bergson’s vitalism speaks of an élan vital held together by the power of memory. Giedion’s stream belongs to the same philosophical conjuncture, the difference however being that it does not take place in the immanence of a consciousness, but in a movement pertaining to an exterior of which consciousness is itself part; but rather than a mere objectivity, this exterior now assumes itself some of the characteristics of subjectivity, or more precisely becomes a kind of subject-object, an intensive field out of which entities emerge.18 Whether this is closer to Husserl or to Bergson remains an open question; it is a possibility inherent in both of them.19

At the same time, this stream of motion into which architecture is as it were submerged, is also what is produced by architecture, no longer taken in the “limited sense,” but as generalized constructive activity; it is not simply dissolved, but retains a capacity to give shape to a stream that otherwise would risk being simply formless. And what its techniques for spatial interpenetration produce is a particular kind of transparency that allows subject and object to remain on the same plane, open to each other, but also an instance of control and regimentation; the openness of interpenetrative space is a function of a constructive power that produces transparence.

Giedion’s proposals might be understood as utopian, and his interpretations of the past were never mere records of facts, but always were oriented toward the opening up of possible futures—they are indeed operative, as Manfredo Tafuri suggested,20 but self-consciously so—which is one of the reasons why his idea of a constructive subconscious had such a massive influence on Benjamin’s work on the Parisian arcades, most directly in the case of the sections on architecture, but also as a general theoretical model for the way in which technology impacts on structures of consciousness and perception, in tearing open a gap in the fabric of time that heralds a coming transformation.21

Benjamin’s suggestions that modern architecture heralds a culture characterized by a positive “poverty,”22 where the use of transparent materials like glass would reduce the space of bourgeois interiority and its psychological depth, are largely derived from Giedion. In this world of poverty, the organic synthesis promised by late nineteenth-century culture would be displaced by the rationalism of the engineer that releases us from a false culture, and makes possible a life that can be lead without “leaving traces.”23 The traces that bourgeois life secretes and accumulates in its shielded interiors sever us from the collective in becoming reified markers of an equally reified individuality, whereas for Benjamin the true task is to forge a mode of life that opens us up to the communal, for which the transparency of new materials, and eventually the new sense of space, is a precondition. “Things made of glass have no ‘aura,’” Benjamin suggests, and “generally speaking, glass is the enemy of the secret. It is also the enemy of possessions.”24

Like Giedion, Benjamin imagines that the new technology will fundamentally change our capacity for perception, even remodel the very categories of space and time, as when in the essay on the work of art in the age of mechanical reproducibility, he argues that cinema functions as a kind of psychoanalysis of the “optical unconscious” that will allow us to see and take possession of space in a different way. Similarly, Giedion and Benjamin both understand the Pont Transbordeur as a condensation of the same kind of technological sensibility that we encounter in the microscope, the telescope, the X-ray image, and the aerial photograph, which eventually would usher in a transformed concept of nature. Benjamin tends however more to stress the role of photographs in allowing us to decipher the city and the relations of labor in a changed perspective, and that technology as such is insufficient, even though he too is ambivalent on this point, as comes across particularly pointedly in the Reproduction essay. For both of them what is ultimately at stake is the possibility of a fusion of nature and technology, or, as Benjamin suggests in a note in the Passagen-Werk: “One could formulate the problem of the new art in the following way: when and how will the worlds of mechanical forms, in cinema, in the construction of machines, in the new physics, etc., appear without our help and overwhelm us, make us conscious of what is natural in them?”25

This opening up, or de-auratization, of the architectural object was intended as a way to create a new social mobility and an openness between groups and classes, and Giedion’s and Benjamin’s proposals can in this respect be taken as paradigmatic for a whole generation of avant-garde thinkers and artists. In hindsight, it is clear that this among many of them (though by no means all) was based on a fantasy of control and exertion of power: transparency and interpenetration erase the division between inside and outside, private and public, and in this they produce a new subjectivity that is attuned to new social demands and programs, for which the architect or artist becomes the organizer.

These ideas form an integral part of early modernist architecture, although the underlying motifs are multiple and entangled. The glassy surface may be read as an instrument for an openness and candor imposed from the outside rather than emerging from the inner spontaneity of the subject, but can also be interpreted as a means of producing opacity or a variable light in order to enhance a sense of pleasure and enjoyment;26 it may fuse interior and exterior in a sweeping movement, or render the passage impossibly difficult by multiplying reflections and doubles.27 Interpenetration may similarly be understood as resulting from a violent application of technological devices to things, which deprive them of their identity, or as the shedding of preconceived essences that restores a sense of openness and laterality, of movement and agency beyond inherited notions of stable substances. Power is both power over... and power to..., with the phantasy of control as a middle term hovering between them. There is a whole history of modern architecture to be written, which would investigate how this phantasm has been negotiated, the contradictions that it harbors, and the way in which it continues to inform the architectural imaginary far beyond the projects of the early modern masters.

This essay was first drafted as an introduction to the special issue of Site in 2014 on “Power, Space Ideology.”

1 Sigfried Giedion, Bauen in Frankreich, Bauen in Eisen, Bauen in Eiesenbeton (Leipzig: Klinkhardt & Biermann Verlag, 1928); Building in France, Building in Iron, Building in Ferroconcrete, trans. J. Duncan Berry (Santa Monica: Getty Center, 1995).

2 Karl Bötticher proposes this distinction in his “Das Prinzip der hellenischen und germanischen Bauweise hinsichtlich der Übertragung in die Bauweise unserer Tage” (1846); translated in Wolfgang Herrman (ed.), In What Style Should We Build? The German Debate on Architectural Style (Santa Monica: Getty Center, 1992). The Kernform (technology) and the Kunstform (tradition) have, in Böttichers reading, after the demise of the classical tradition, entered into a conflict, and a new synthesis is required, for which iron constructions will provide the structural basis, even though the aesthetic moment still has to remain Greek. In Bötticher’s main work, Die Tektonik der Hellenen (1844-52), he investigates the statics of Greek temples, and understands form basically as a language that is able to express the laws of mechanics: the forms signify that which in itself is only a function (the column signifies the bearing of a load), and thus makes it into a self-reflexive structure (an interpretation that can already be found in Hegel’s Lectures on Aesthetics, which is the hidden source for many of these debates). For a discussion of Bötticher, see Manfred Klinkott,”Die Tektonik det Hellenen als Sprachlehre und Fessel der klassizistischen Baukunst,” in Hans Kollhoff (ed.), Über Tektonik in der Baukunst (Braunschweig: Vieweg & Sohn 1993). For a survey of the nineteenth century debate of art-form and core-form, which passes through several stages and constitutes one of the essential foundations of architectural modernism, se Werner Oechslin, Stilhülse und Kern: Otto Wagner, Adolf Loos und der evolutionäre Weg zur modernen Architektur (Berlin: Ernst & Sohn, 1994).

3 Building in France, 87.

4 The bridge was one of the technological icons of the time and the subject of photographs by Germaine Krull as well as a film by Moholo-Nagy, Marseille, Vieux Port, from 1929.

5 Giedion, Building in France, 169.

6 For a discussion of Giedion’s various uses of “interpenetration,” see Hilde Heynen, Architecture and Modernity: A Critique (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT, 1999), 30ff.

7 For a collection of source documents, with a detailed historical introduction, see Harry Francis Mallgrave and Eleftherios Ikonomou (eds.), Empathy, Form, and Space: Problems in German Aesthetics, 1873–1893 (Santa Monica: Getty Center, 1994).

8 See Foucault, Les mots et les choses (Paris: Minuit, 1966), 329–333.

9 See the introduction in Gustav Theodor Fechner, Vorschule der Ästhetik (Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1876), 1–7. The book, which contains the most cited formulas, is Fechner’s last, but the ideas of an “experimental aesthetics” had appeared in many of his earlier writings, and he can be said to have initiated the new turn.

10 Über das optische Formgefühl: Ein Beitrag zur Ästhetik (Leipzig: H. Credner, 1873), 40.

11 In Husserl and other early phenomenologists, notably Edith Stein (Zum Problem der Einfühlung, 1917), the problem of empathy is mostly seen as an epistemological issue, and aesthetics plays no role; conversely, as phenomenological aesthetics begun to develop in the circle around Husserl, empathy received little attention, and when Werner Ziegenfuss summarized the early discussions in his dissertation Die phänomenologische Ästhetik (Berlin: Arthur Collignon, 1928), the concept does nor appear. Later scholars have attempted to retrace these connections, although they are still relatively obscure; see Gabriele Scaramuzza’s pioneering Le origini dell’estetica fenomenologica (Padua: Antenore, 1976), 132

12 For the idea of art as the highest metaphysical activity, see the final sentence in “Preface to Wagner” in Der Geburt der Tragödie, Kritische Studienausgabe, eds. Colli-Montinari (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1999), 1:24. The later remark on aesthetics as “applied physiology” is made in the context of an attack on Wagner, and we should not immediately see this as exhausting the possible meanings of aesthetics for Nietzsche: “My objections to Wagner’s music are physiological objections: and why still dress them up in aesthetic formulas? Aesthetics is, to be sure, nothing but applied physiology.” (“Meine Einwände gegen die Musik Wagners sind physiologische Einwände: wozu dieselben erst noch unter ästhetische Formeln verkleiden? Ästhetik ist ja nichts als eine angewandte Physiologie.”) Nietzsche contra Wagner, Kritische Studienausgabe, 6:418. On perspectivism and the overthrowing of Platonism as a “new interpretation of sensibility,” see Martin Heidegger, Nietzsche I (Pfullingen: Neske, 1961), 231–254.

13 In order to correctly use the “weapons of the senses,” Baumgarten suggests, we need to immerse ourselves in “aesthetic empirics” (ästhetische Empirik), which involves all aspects of the situation, from the purely physiological responses of the body to technical instruments like microscopes and telescopes, barometers and thermometers, all of which have in common that they prolong and expand our senses. See the second of his “Letters to Aletheiophilus,” in Baumgarten, Texte zur Grundlegung der Ästhetik, ed. Hans Rudolf Schweizer (Hamburg: Felix Meiner, 1983). 134

14 For the connection between Leibniz’s conception of vis plastica and Wölfflin’s analysis of Baroque art, see Gilles Deleuze, Le Pli: Leibniz et la baroque (Paris: Minuit, 1988), 6.

15 As Husserl deepens the analysis of intentionality and its embodiment, he eventually hits upon the earth as the unmovable background of all theoretical acts, an “originary ark” that constitutes a background for all of our spatial intuitions. Husserl’s fragment, “The Earth as Originary Ark Does not Move,” was written in 1934, the year before Heidegger’s “The Origin of the Work of Art,” with which it shares many motifs. For an attempt to cross-read some of these issues, see my “Husserl and the Earth,” in Tora Lane and Marcia Sá Cavalcante Schuback (eds.), Disorientations: Philosophy, Literature and the Lost Grounds of Modernity (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014).

16 Other important texts from the period include Theo van Doesburg, Grundbegriffe der neuen gestaltenden Kunst (1925), and Moholy-Nagy, von material zu architektur (1929). The latter concludes with a celebration of Gropius’s Bauhaus building in Dessau and Brinkmann and van der Flugt’s Van Nelle factory in Rotterdam, both of which evince an “illusion of spatial interpenetration of a kind that only the subsequent generation will be able to experience in real life—in the form of glass architecture.” Moholy-Nagy, von material zu architektur (Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 2001), 236.

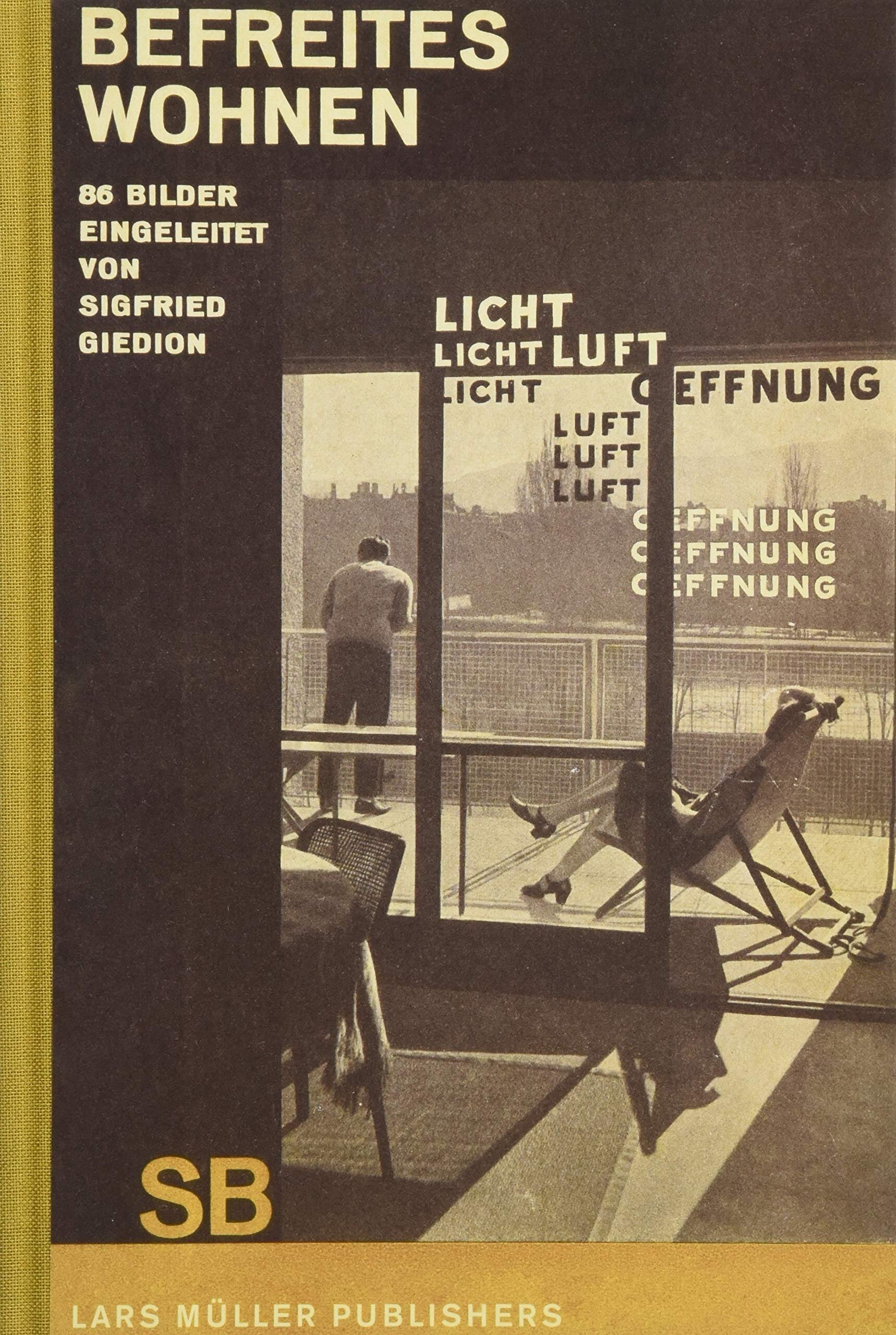

17 Building in France, 90. Here Giedion’s radical proposals make a halt in front of the domicile, and he emphasizes that we should not attempt to “carry over into housing this absolute experience that no previous age has known” (91). In the following book, Befreites Wohnen (1929), Giedion takes this further step by which interpenetration explicitly erases the limit between private and public, and he rejects the idea that the sheltering aspect of domestic space could have a transhistorical value. “Today we need a house that corresponds in its entire structure to our bodily feeling as it is influenced and liberated through sports, gymnastics, and a sensuous way of life: light, transparent, movable. Consequently, this open house also signifies a reflection of the contemporary mental condition: there are no longer separate affairs. Things interpenetrate (Die Dinge durchdringen sich).” Giedion, Befreites Wohnen (Zurich: Orell Füssli, 1929), 8.

18 Elsewhere I have tried to show that the same idea can be found in Malevich’s “non-objective world” (gegenstandslose Welt, literally “without objects,” bespredmetnost). It is not a world that would be simply lacking objects, but a field that art must attain through a process akin to the phenomenological reduction, and out of which objects emerge. See my Essays, Lectures (Stockholm: Axl Books, 2007), 186ff.

19 This element of exteriority is probably closer to Bergson, at least if we follow Deleuze’s interpretation; see Deleuze, Le bergsonisme (Paris: PUF, 1964). Husserl’s famous dictum “we are the true Bergsonians” instead takes this exteriority back into consciousness; for Husserl’s statement, assumed to have been made in a discussion with Alexandre Koyré, see Bernard Waldenfels, Phänomenologie in Frankreich (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1987), 21.

20 “Operative criticism” for Tafuri refers to an analysis that scans history in search of aesthetic norms, and which constructs its genealogies of the present in search of future action. This criticism, he writes “has as its objective the ‘planning’ (‘progettazione’) of a precise poetical tendency, anticipated in its structures and derived from historical analyses programmatically distorted and finalized,” it is a “meeting point of history and planning” and “plans (progetta) past history by projecting it (proiettandola) towards the future.” Tafuri, Teorie e storia dell’architettura (Bari: Laterza, 4. ed. 1988), 161; Theories and History of Architecture, trans. Giorgio Verrecchia (London: Granada, 1980). 141. Operative criticism is closely linked to the idea of architecture as a project, which is a highly polysemic term in Tafuri, as is indicated by the English translation of the quote above; see my discussion of this term in Architecture, Critique, Ideology: Writings on Architecture and Theory (Stockholm: Axl Books, 2016), 11ff.

21 Upon receiving the book, Benjamin writes to Giedion: “When I received your book, the few passages that I read electrified me in such a way that I decided not to continue with my reading until I could get more in touch with my own related investigations.” (Benjamin, letter to Giedion February 15, 1929, cited in Sokratis Georgiadis’s preface in Giedion, Building in France, 53). For the relation between Benjamin and Giedion, see Detlef Mertins, “Walter Benjamin’s Tectonic Unconscious,” Any 14 (1996), and “The Enticing and Threatening Face of Prehistory: Walter Benjamin and the Utopia of Glass,” Assemblage 29 (1996). Tafuri, notwithstanding his constant references to Benjamin, seems to have overlooked this connection, which places both Benjamin and Giedion on the operative side.

22 See Benjamin, “Erfahrung und Armut” (1933), Gesammelte Schriften (GS) (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1997), GS 2/1:213–19. Cf. Das Passagen-Werk: “It belongs to the technical forms of Gestaltung that their progress and success are proportional to the transparency of their social content (glass architecture comes from this)” (GS V:581).

23 “This was something to which Scheerbart with glass and Bauhaus with steel had opened a path: they have created rooms where it is difficult to leave traces.” (“Erfahrung und Armut,” 217) To “erase the traces” is the theme for Benjamin’s commentary to a poem by Brecht from Lesebuch für Stadtbewohner; see Benjamin, Versuche über Brecht (GS II/2), where it assumes a rather different meaning and points to the condition of the urban revolutionary, for whom the city has lost all aesthetic qualities and has become a battleground. Erasing the traces here becomes a strategy for escaping surveillance and control, rather than a positiv program for a new life.

24 “Erfahrung und Armut,” 217. The idea of a world without possessions, or rather one that would make possible a different relation to the object than the one organized along the lines of use and exchange value (with their inherent tendency to fetishism), was a crucial theme among some constructivist theoreticians, notably Boris Arvatov. See Christina Kiaer, Imagine no Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT, 2005).

25 23. Das Passagen-Werk, GS V:500 (my italics).

26 Benjamin’s direct reference when it comes to the use of glass is the poet Paul Scheerbart, whose visions in Glasarchitektur (1914) of a world based on transparency acted as a catalyst for many in the early avant-garde. Scheerbart’s book was aiming at a moral change of man, but it was also a poetic sketch that resists any unambiguous and programmatic readings. Scheerbart imagines how glass architecture would evolve from a singular building until it covered the whole face of the earth, providing a complete enlightenment, an infinite luminosity. While there is a austerity and poverty in Benjamin’s fascination with transparency, Scheerbart stresses the sensuous and voluptuous aspects of glass—what attracts him is not so much transparency, and definitely not any kind of austerity (and on this point he seems to have been misread by many avant-gardists), as the possibility of modulating light and shade, heat and cold, and the achievement of a state of maximum comfort and luxury, where interior and exterior blend together in a delightful continuity and our homes become “cathedrals” for the fulfillment of desires. We have to get rid of our nostalgia for the heavenly paradise, Scheerbart suggests, so that we may realize it here and now in terms of a hedonist culture based on luminosity.

27 A crucial reference would here be Colin Rowe and Robert Slutzky’s 1964 essay “Transparency: Literal and Phenomenal,” which attempt to spiritualize technology by defending the autonomy of architecture as art from the attacks mounted by the historical avant-garde. Rowe and Slutzky fuse together the themes of transparency, interpenetration, and space-time in a formalist conception that makes it possible to read the trajectory of modern architecture as pointing towards an autonomy, self-reference, and aloofness from the world that preserve the depth and values of a humanist culture, and for which the analogy with painting will be essential. For a discussion of this, see my The Silences of Mies (Stockholm: Axl Books, 2008), 59-63.