Spoon Carving: A Philosophical Investigation

Johan Sandås

I’ve been making wood sculpture for a number of years now, constantly trying to simplify and refine my work until I finally reached a point where I could only make wooden spoons. And why should I do anything else, really? As I’m sure the reader will agree, the wooden spoon contains all possible shapes. And the tools that shape the wood represent, in a way, all possible tools.

Wood is not the only possible material, but as I will demonstrate in this article, wood is the first material, the material from which the very idea of materiality is derived. Once upon a time, there was a need to distinguish between form and material, and the material that was chosen was wood. The form, on the other hand, is related to the idea, to the thought, and to the invisible things that happen in the brain. Invisible, that is, until one finds a way to take a look.

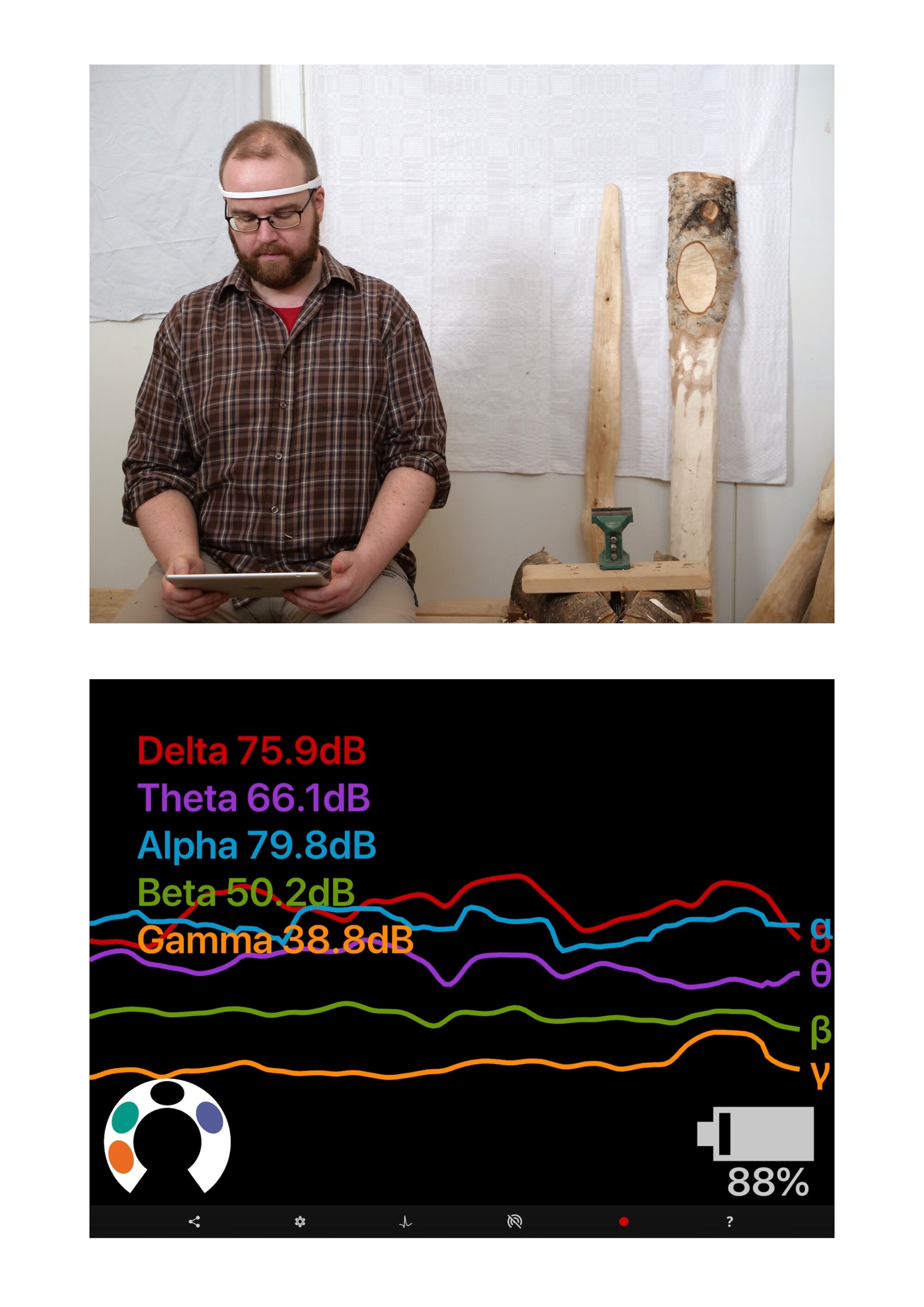

In the course of my research I came across a simple device that lets me detect my brain waves, and then show them on a screen. The device I’m using is called the Interaxon Muse, and the app that displays the brainwaves on a screen is called Mind Monitor. There may be others.

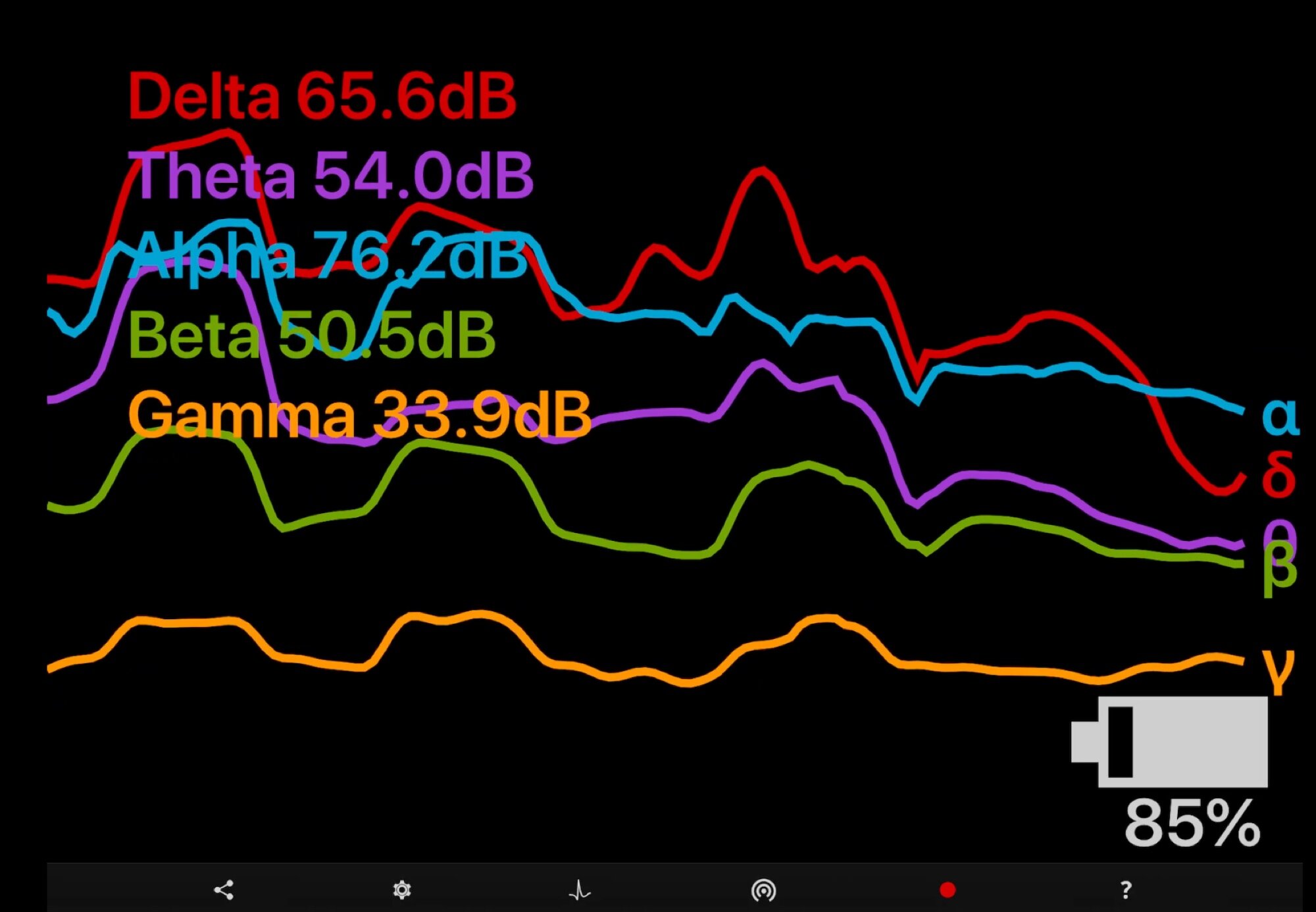

This is what my brain waves look like when I’m not doing anything in particular. We’re seeing the pure world of ideas here, and at a first glance there’s nothing much to see. The brainwaves are more or less in synch and fairly close together.

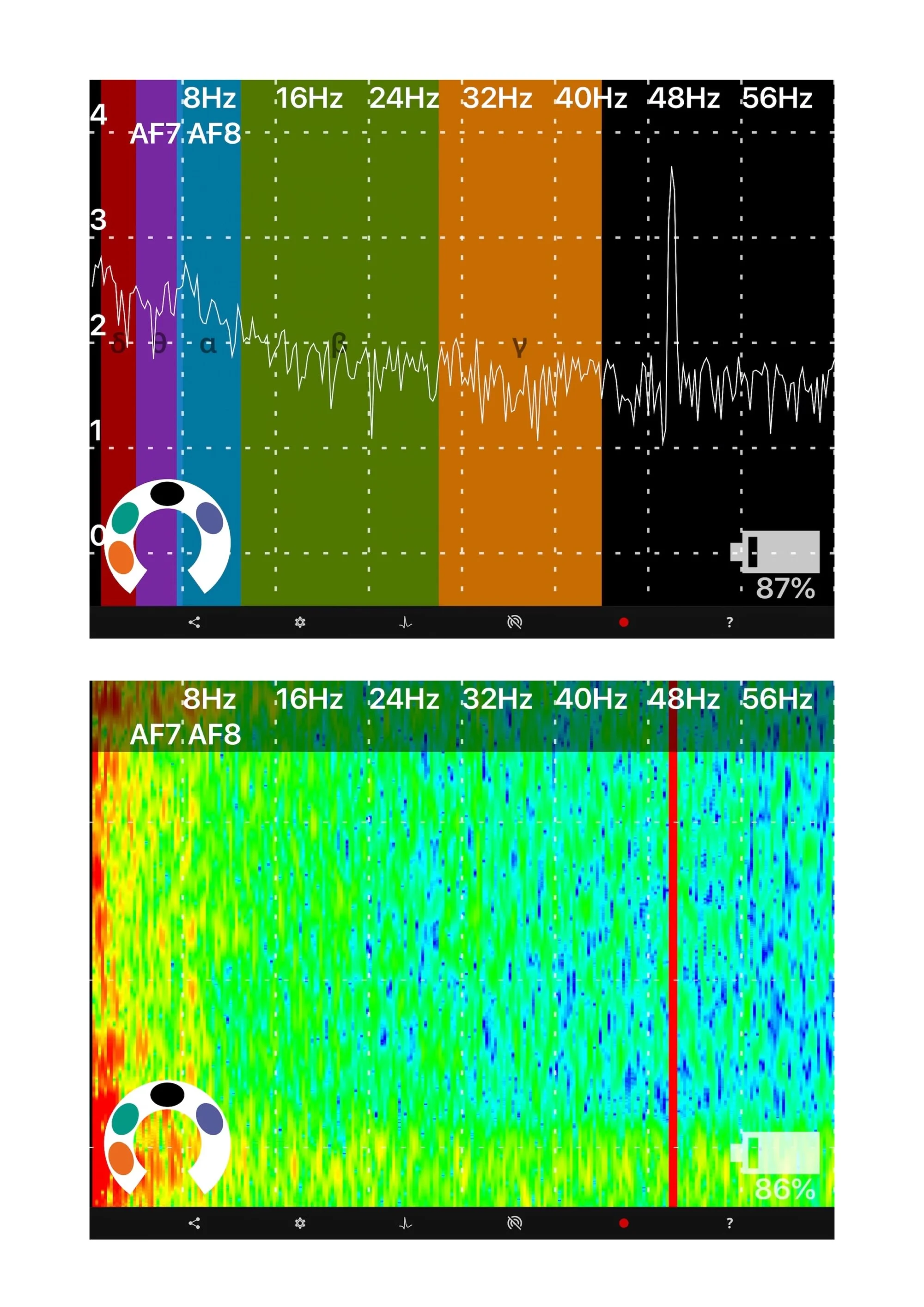

The device I’m using lets me display brainwaves in many different ways. At this point I don’t know what any of them mean, but here are two other views of the same moment:

As you can see, the device measures brain waves in decibel (dB) in the first view, and in Herz (Hz) in the other two. What does this mean? If these waves were sound waves, the first view would be how loud the sound is, and the second to how hight the frequency is. What does it mean when it comes to brain waves? What does anything mean?

There’s a sudden spike at 50Hz, shown as a protrusion in the jagged line of the second graph, and as an angry red line in the third. I interpret this to mean that there’s an increase in activity at this point of the brainwave spectrum, but when I take off my headband the red and green graph turns entirely red, so maybe it means the opposite. Whether it means one thing or another, I choose to believe that this is a sign of a wandering mind. When your mind wanders, this place on the brainwave graph is where it goes (it’s also possible that the 50Hz spike is just some noise in the system, signifying nothing). I did the research that’s presented in this article over the course of three non-consecutive days. If anyone starts wondering why the battery percentages in the bottom right corner keep going up and down, this is why.

Anyway, back to the topic at hand: I’m interested in craft, and in simple materials and the shape of functional objects. But if this was all I was interested in, I wouldn’t need to go digging around in my brain or pretend that I understand philosophy, it would be enough to just do the things. The reason I’m going about my work this is that I’m trying to find the point where the material meets the immaterial, which I hope will lead to some useful and interesting results. I’m interested in materiality itself, and why there is something instead of nothing.

When we talk about the materiality of things, there’s also always the question of the materiality of the body, which Judith Butler has written about in Bodies that Matter. The book says things better than I ever could, and I won’t try to summarise it here. It’s a good read, you should pick it up once you’re finished with this. As for the ongoing debate about material versus immaterial art, there’s a discussion of this topic in Dorothea von Hantelmann’s book How to Do Things with Art, especially in the chapter about Tino Seghal. I don’t have either of those books at hand right now, but I nevertheless think that reading a book might be an interesting second baseline for my brainwave measurements, before I get into the real matter of this investigation. I will take a look at my brainwaves while reading the book Spacing Philosophy: Lyotard and the Idea of the Exhibition by Daniel Birnbaum and Sven-Olov Wallenstein. In the rest of my research I will use this graph to represent a moderate amount of concentration.

As you can see, the red line around 50Hz is completely gone now and the graph is almost fully green. I can’t imagine that it’s the book-in-itself that’s doing this, my devices aren’t nearly sensitive enough to see that I’m reading. What we’re seeing here, I imagine, is concentration.

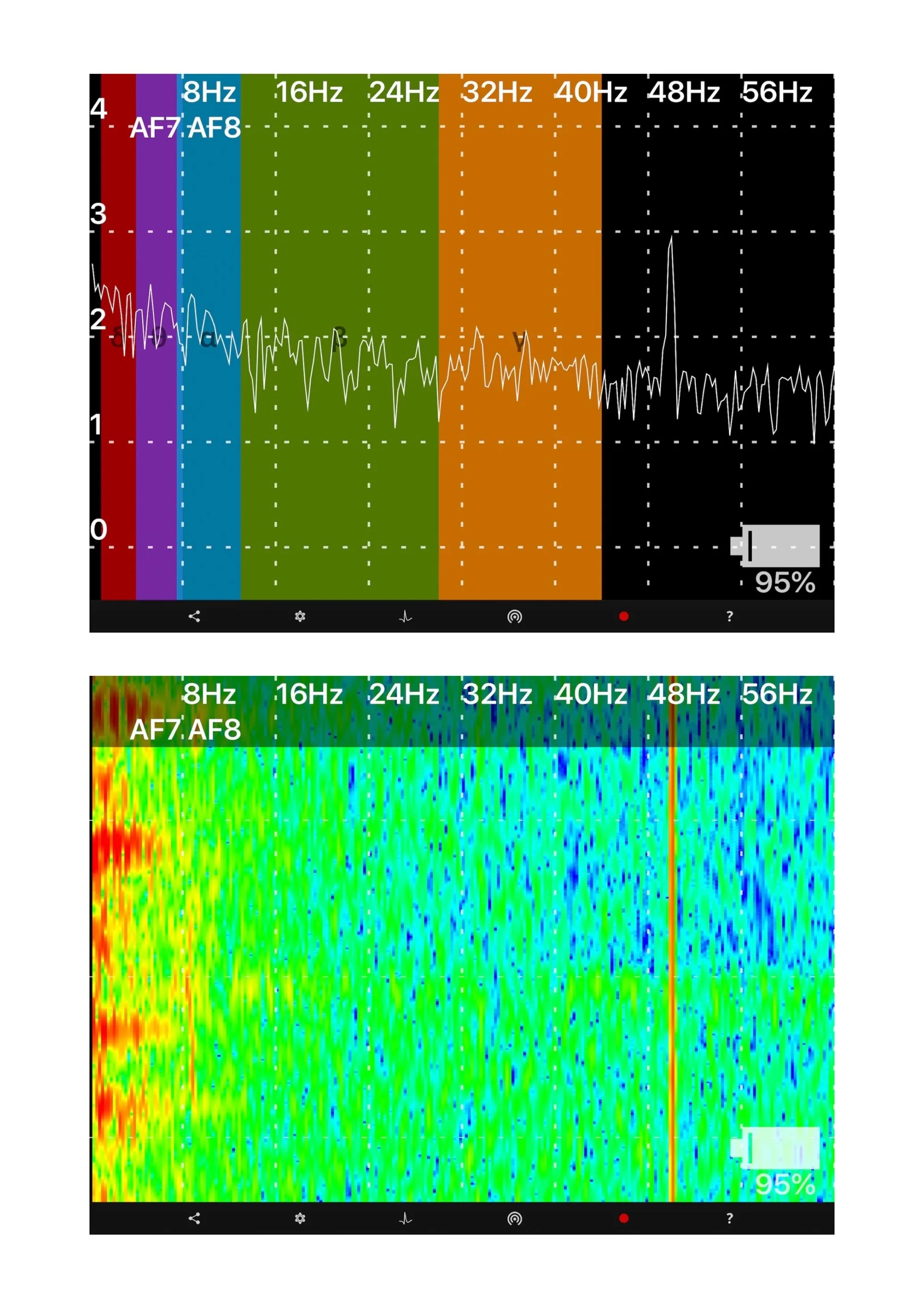

I realise that the connection between the topic of this book on the one hand — Jean-François Lyotard’s 1985 exhibition “Les Immatérieux” at Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris — and my own interest spoon carving on the other may not be apparent at the moment. So maybe it’s time to get to the real material of my research project. This is what’s going on in my brain while I carve a spoon:

As you can see, this looks remarkably close to nothing, and not at all like reading a book. As the work progresses, my concentration increases until the brainwave display starts to look more and more like the focused state of reading a book. As we will see later, simply holding a finished spoon in my hand also looks almost completely like the baseline wandering mind, while using the spoon for its intended purpose creates a brainwave image closer to that of concentration.

This might be the place to mention that the brain sensing headband also picks up movement, especially of the eyes but also of the hand and the jaw. This would make my findings nearly useless for any kind of scientific research, but for my own artistic purposes I see no particular problems. Movement is simply thinking that happens in the hands.

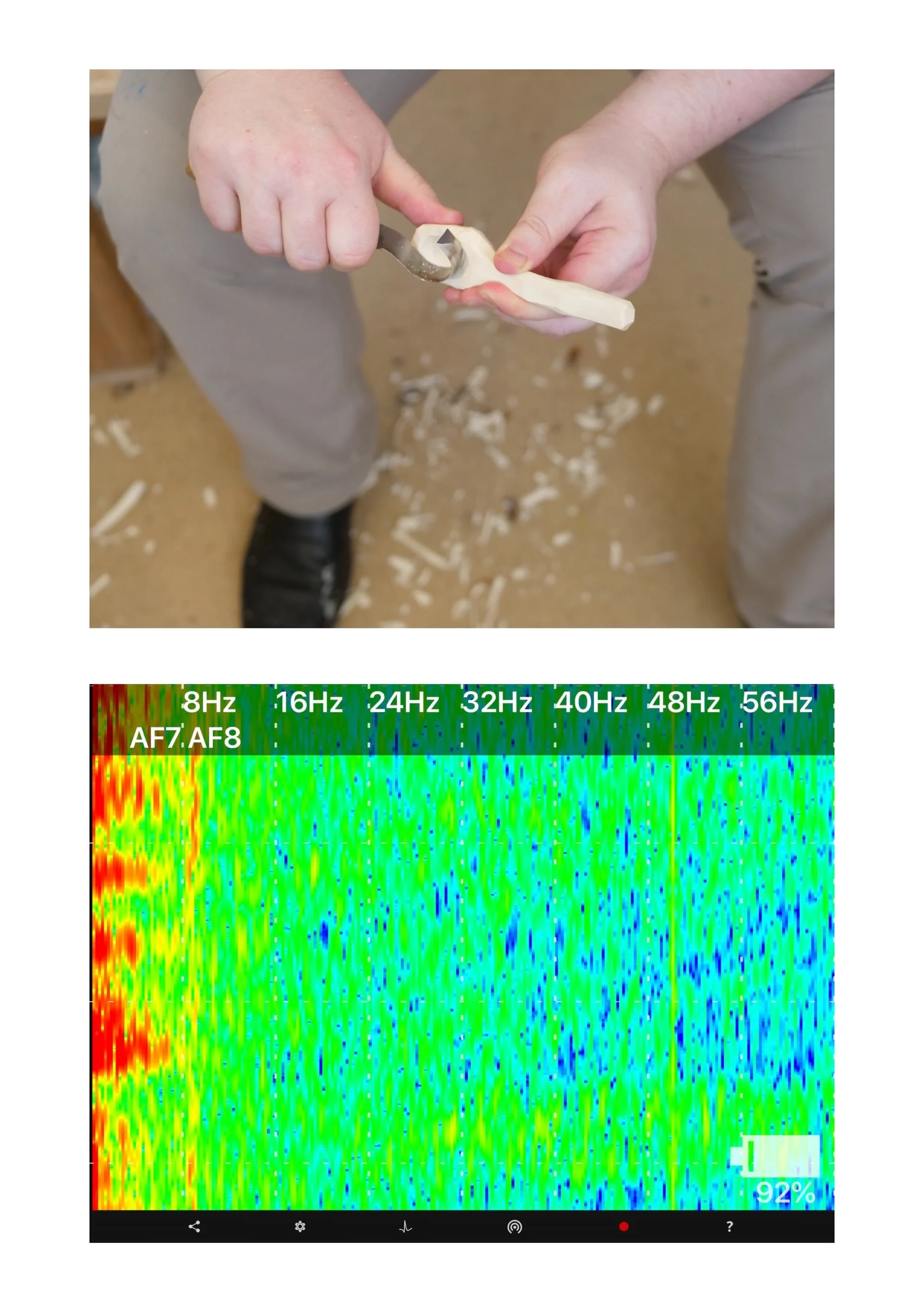

Here are some closeups of the process of spoon carving: the moment, as it were, when nothing becomes something.

The brainwave graph suddenly resolves into an image of concentration, with no traces of a wandering mind. And this is not caused by the specific tool at hand, because using another tool instead yields a very similar image:

At this point I will also take the opportunity to try to explain why I’m so interested in wood as a material. It’s well known that the original Greek word for materia, used by Plato and no doubt other ancient Greeks, was hyle, which literally means wood. There are plenty of sources that confirm this; I have chosen a passage from Vilém Flusser’s essay “Form and Material”, first published in English in 1999 but no doubt written earlier while he was still alive. Like many people, he approaches the material from the starting point of the immaterial:

“A lot of nonsense has been talked about the word immaterial. But when people start to speak of ‘immaterial culture’, such nonsense can no longer be tolerated. This essay aspires to clear away the distorted concepts of the ‘immaterial’.

The word materia is the result of the Romans’ attempt to translate the Greek term hyle into Latin. Hyle originally meant ‘wood’, and the fact that the word materia must have meant something similar is still suggested by the Spanish word ‘madera’. When, however, the Greek philosophers took up the word hyle, they were thinking not of wood in general but of the particular wood stored in carpenters’ workshops.” (Flusser, Vilém. “Form and Material”, published in the collection The Shape of Things, page 22)

It’s quite possible that it’s Lyotard that he’s talking about when he says that people have started to speak of immaterial culture. Flusser was terrible at citing his sources. The Greek philosopher he refers to, the one who took up the word hyle, is almost certainly Plato. I would not presume to know whose wood Plato was thinking about at the time. I wasn’t there with my brain sensing device. And besides, it might have been Aristotle.

I see no reason to doubt that Flusser is correct about the meanings of the words themselves. I myself know little Latin and even less Greek, but these things can easily be looked up. However, Flusser follows that up with a couple of sentences that make me doubt that he ever tried making anything from wood himself:

“In fact, what they were concerned with was finding a word that could express the opposite of the term form (Greek morphe). Thus hyle means something amorphous.” (Flusser, “Shape and Material”)

My own experience has shown that wood is far from amorphous, and definitely not something that you can find in a pure conceptual state without any limitations as to what form it can be turned into. In fact, the closer we get to taking the wood straight from the tree, the more strongly the material suggests and encourages certain forms. And even wood that has been stored in a workshop for years sometimes has such a strong inherent form that it can really only be made into one thing: a spoon.

An interesting thing about the exhibition “Les Immatérieux”, apart from nobody really remembering what it was like, is that I’ve read suggestions from several sources that before Lyotard put the word ‘immaterial’ on display, there hadn’t been much interest in the concept of ‘material’ either. The art historian Monika Wagner, for example, claims that discussing material at all in an aesthetic context is something fairly new, which has only come about because the lowly everyday word ‘material’ has become connected with the established philosophical term ‘materia’. Materia, in turn, became fashionable after its opposite, the immaterial, was brought into focus by Lyotard’s exhibition in 1985.

“The exhibition, with the programmatic title that translates material into its opposite […] displayed not only objects but also image and text programmes generated by computer technology. It asked questions about how the technical development of information systems changed perceptions about the materiality of things.” (Wagner, Monika. “Material”. Published in Documents of Contemporary Art: Materiality, page 26)

In their book Spacing Philosophy, Birnbaum and Wallenstein trace the history of this exhibition back through Lyotard’s writings, and present the hypothesis that the exhibition was in fact an extension of Lyotard’s philosophy. “Les Immatérieux” should not be seen as an attempt to illustrate his written philosophy, but as an attempt to do philosophy in some other form than language, the spatial form of an exhibition.

For me as an artist, it’s very tempting to say that I, too, want to do philosophy in the form of an exhibition. I suspect that this desire comes from a feeling that only doing art, only making things, isn’t good enough, and I need to connect what I do to the thoughts and ideas of others. Sometimes I feel that I as an artist am somehow kept down by the oppressive ideas of — someone. Certainly not philosophers. Even though Plato presumably claimed that artists were bad and only wanted to trick people, making the public believe I’ve made a table when I’ve only made a picture.

In reality, of course, I’m not oppressed at all. In fact I’m quite privileged, in that I get to do what I want most of the time and can afford to eat, even if it’s mostly oatmeal. And it turns out I was wrong about Plato, too. He does not say that artists trick people into believing that they’ve made a real table.

“Now let me ask you another question: Which is the art of painting designed to be — an imitation of things as they are, or as they appear — of appearance or reality?

Of appearance.

Then the imitator, I said, is a long way off the truth, and can do all things because he lightly touches on a small part of them, and that part an image. For example: A painter will paint a cobbler, carpenter, or any other artist, though he knows nothing of their arts; and if he is a good artist, he may deceive simple persons, when he shows them his picture of a carpenter from a distance, and they will fancy that they are looking at a real carpenter.” (Plato. The Republic, page 255)

Not a fake table, then, but a fake carpenter.

Such nonsense can no longer be tolerated.

Just for fun, we can try to trace the roots of material culture deep into prehistory. In a 2016 article, the archaeologist Fiona Coward claims that object-making has in fact been an important part of the development of the human brain:

“Many other species besides Homo Sapiens are tool-users and even tool-makers, but one aspect of material culture still sets modern humans apart: our emotional and social engagement with objects. […] Material culture plays a vital role in conveying social information about relationships between people, places and things that extend geographically and temporally beyond the here and now — a role which allowed our ancestors to off-load some of the cognitive demands of maintaining such extensive social networks, and thereby surpass the limits to sociality imposed by neurology alone.” (Coward, Fiona. “Scaling Up: Material Culture as Scaffold for the Social Brain” (published in Quaternary International, issue 405, 2016)

I think it’s interesting to put this in close proximity to a classic quote by Marx, which can be found in Birnbaum and Wallenstein’s book:

“It is absolutely clear that, by his activity, man changes the forms of the materials of nature in such a way as to make them useful to him. The form of wood, for instance, is altered if a table is made out of it. Nevertheless the table continues to be wood, an ordinary, sensuous thing. But as soon as it emerges as a commodity, it changes into a thing which transcends sensuousness. It not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relation to all other commodities, it stands on its head, and evolves out of its wooden brain grotesque ideas, far more wonderful than if it were to begin dancing of its own free will.” (Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Quoted in Birnbaum and Wallenstein, Spacing Philosophy, page 31)

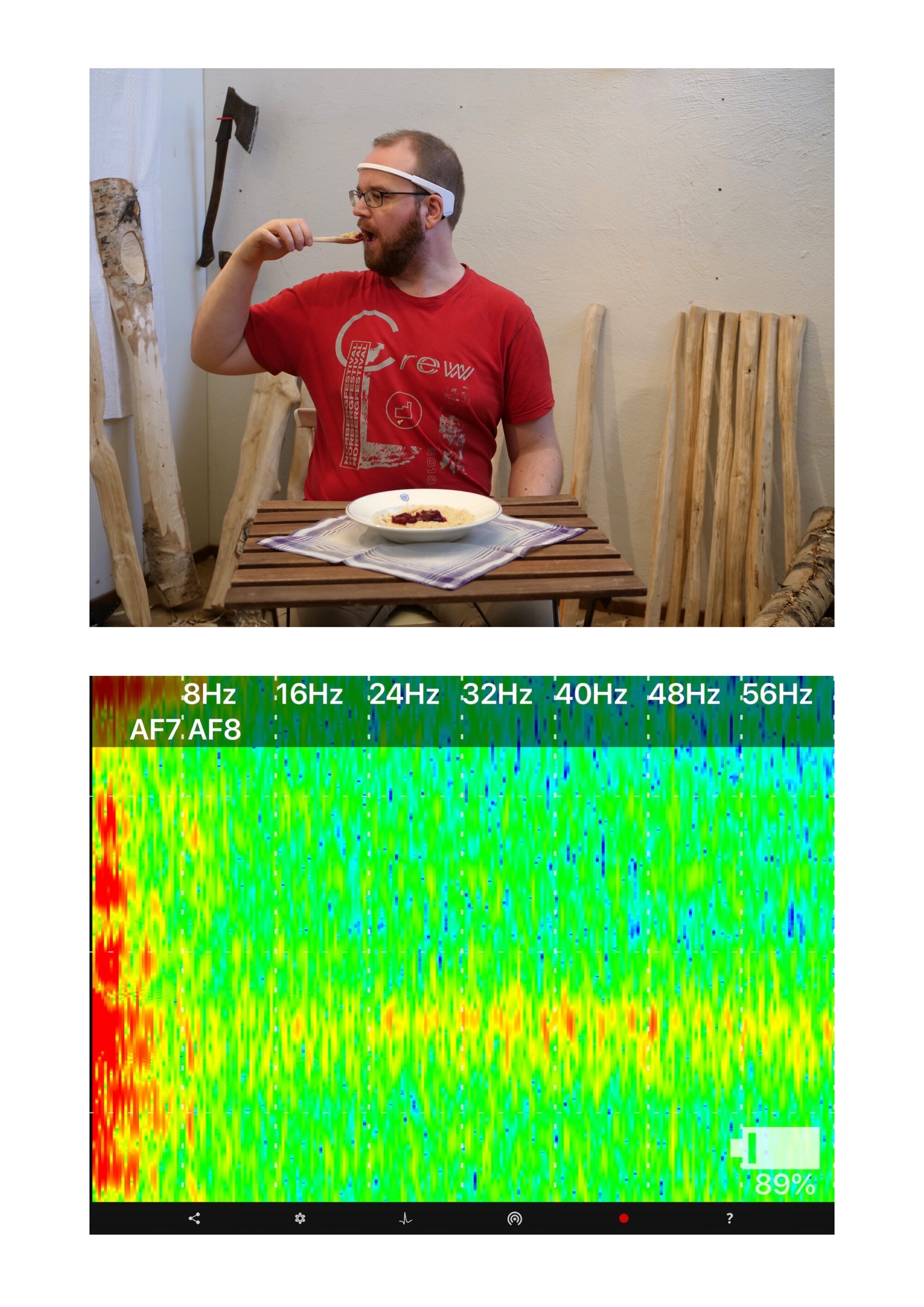

I will leave it to the reader to figure out the connections between the material culture of our earliest ancestors, that of early industrialisation, and the material and immaterial cultures we live under now. As for me, I will make some oatmeal porridge and trace my brainwaves while eating it.

The material cost of this symbolic meal was as follows: three cartons of oatmeal for 45 cents each, and two plastic jars of lingonberry jam for approximately 2.50€. Why did I buy so much porridge and jam, you may ask. Am I really going to use all of it for artistic research, or was I planning to eat some of it for breakfast? The whole project is highly suspect from the start.

Johan Sandås has been an artist for ten years, and has made wood sculpture for five. He's interested in the sustainable use of natural resources, free and equal access to knowledge, and food. He has a masters degree in art and culture from Novia University of Applied Sciences, Finland.

This project is still in its early stages of development, and has been made possible partly thanks to a grant from Svenska Kulturfonden/Svenska Österbottens Kulturfond.