New Forms of Knowledge

Jonas (J) Magnusson

“Such are the stakes: to know, but also to think non-knowledge when it unravels the nets of knowledge. To proceed dialectically, beyond knowledge itself, to commit ourselves to the paradoxical ordeal not to know (which amounts precisely to denying it), but to think the element of non-knowledge that dazzles us whenever we pose our gaze to an art image.”

(Georges Didi-Huberman, Devant l’image, 1990)

“What is the use of art history?” asks Georges Didi-Huberman in Devant le temps (2000). His answer: Not much, if it contents itself with a prudent classification of objects that are already known, already identified; quite a lot, if it succeeds in placing non-knowledge at the centre of its complex of problems, and if it succeeds in making this complex of problems an anticipation, the opening of a new knowledge, a new form of knowledge.

Exploring a critical archaeology of art history, in books like Devant l’image and Devant le temps Didi-Huberman sets out to disentangle multiple lines, to emphasize the counter-times and anachronisms that syncopate the exuberance of images, upstream of the canons of symbolic form and the temporal models applied by the historian’s discipline. In this quest Didi-Huberman has been preceded by an “anachronistic constellation” of thinkers: Walter Benjamin, Aby Warburg, and Carl Einstein. The rereading of these historical figures in Devant le temps responds to a triple desire, a triple stake: archaeological, anachronistic, and prospective. Warburg: the creator of the library (in Hamburg, then in London) that bears his name, the shadow-founder of the discipline known as “iconology,” an adventurous thinker aiming for a symptomatological interpretation of a culture through its images, its beliefs, its dark continents, its residues, its shifting of origins, its returns of the repressed — but nevertheless strangely ignored by historians and philosophers. Benjamin: more than famous among philosophers, but also the founder of a certain history of images by his “epistemo-critical” practice of montage, inducing a new form and content of knowledge in the context of an original and revolutionary conception of historical time. Einstein: almost forgotten today (except by a couple of anthropologists interested in African art and some avant-garde historians interested in cubism, Georges Bataille and the journal Documents), in spite of the fact that he invented new objects, new problems, new historical and theoretical areas — paths opened up by taking an extremely anachronistic risk, the heuristic movement of which Didi-Huberman tries to restitute as much as possible.

“My way of speaking is not systematic,” Carl Einstein writes in 1923; a confession of fragility, but also a vengeance against all systematic tendencies, all axiomatic approaches. Refusing to simplify art, Einstein prefers the risk of the uncompleted, multifocal and exploded. In its “cubistic” form, what Einstein’s project demands of art history is a heuristic approach: to let the image play or “work” in view of unforeseen concepts, unexpected logics. “I only believe in people who begin by destroying the means of their own virtuosity. The rest is only petty scandal,” he writes in Documents in 1930, refusing to capitalize on his competences, his intellectual work, his knowledge. For Einstein, in the reading of Didi-Huberman, the act of practicing a knowledge thus always responds to an act of questioning it, with the risk of momentarily destabilizing or delegitimizing it, but in order to be better able to open it up. This would be one of the reasons why Einstein — rejecting the institutions but not wanting to “save” himself either — never spoke “in a systematic way.” This is also one of the reasons why he is so forgotten today, and one of the reasons behind the difficulty that still remains when “using” his work in the field of art history.

Anita Ree, Portrait of Carl Einstein, before 1921

A re-examination of the notion of “history” in art history — this is one of the challenges of Devant le temps: a critical archaeology of the models of time, of the use values of time in the historical discipline that wanted to make images its object of study. The starting-point is that which for many historians seems to be most evident: the rejection of the anachronism. Never “project” your own realities — concepts, preferences, values — on the realities of the past, on the objects of the historical investigation! Lucien Febvre’s damnation of the anachronism is well known: “the sin of the sins — the most unforgivable of sins: the anachronism.” At the same time, Didi-Huberman reminds us, the anachronism keeps intersecting and flashing through every form of contemporaneity. There is (as Marc Bloch already pointed out in Apologie pour l’histoire ou Métier d’historien, 1942–1943) a structural anachronism that no historian is able to escape: it is impossible to understand the present without knowledge of the past, but it is also necessary to know the present in order to understand the past and to be able to question it. In reality, there would be no history that is not anachronistic, anachronism being the only way in historical knowledge to account for the anachronies and polychronies of history, the temporal way to express the exuberance, complexity, and over-determination of images (anachronism seeming to emerge in the exact fold of the relation between history and image).

The anachronism, then, would be a necessary risk in the activity of the historian, the condition of possibility of the discovery and the constitution of the objects of his knowledge. The problem is the unthought anachronism. This is why the Didi-Hubermanian art historian has to commit another one of the mortal sins according to Lucien Febvre: to “philosophize.” Didi-Huberman, for example, hints to a possible relation between the concept of anachronism and Gilles Deleuze’s “time-image,” with its double reference to montage and to “divergent movement.” It is possible, he writes, that there is no interesting history except in montage, in the rhythmical play, the contradance of chronologies and anachronisms. Images are always complex time-objects: montages of heterogeneous times that form anachronisms. And in the dynamics and complexities of these montages, fundamental historical concepts like “style” or “epoch” are suddenly found to be extremely plastic. To raise the question of the anachronism would thus be to explore this radical plasticity and, together with it, the mixture of time-differences at work in every image. Fra Angelico, for example, is an artist who also manipulates times that are not his own, creating a strangeness in which the fecundity of the anachronism is affirmed. The drippings of Pollock, of course, cannot serve as an adequate interpretant for the violently material rain of colored spots on the lower panels (never commented in the principal monographs and catalogues on Fra Angelico) of Fra Angelico’s Madonna of the Shadows (c. 1440–1450) discovered by a surprised Didi-Huberman in a corridor of the monastery of San Marco. But that does not mean that the art historian, in front of this chock of a “displaced resemblance” or a “relative defiguration,” gets away so easily. For the paradox remains, the anxiety in the method: that the suddenly emerging historical object as such would not have been the result of a historical standard method, but of an almost irregular anachronistic moment, something like a symptom in the historical knowledge (this strange conjunction of difference and repetition denoting a double paradox: interrupting representation, but also carrying with it an unconscious of history). In reality it would be this very violence and incongruity, this very difference and non-verifiability, which would have produced a kind of heaving of censorship, the emergence of a new problem for the history of art. This is the heuristics of the anachronism according to Didi-Huberman. It is an approach that seems contrary to the axiomatic historical method, constituting a rhythmical interruption in it, a syncopated, paradoxical, often dangerous moment, but one that may lead to the discovery of new historical objects. Endowed with the capacity of complexifying models of time, traversing multiple memories, re-establishing the fibers of heterogeneous times, rearranging rhythms of different tempi, the anachronism thus obtains a renewed, dialectical status; as the cursed part of the historical knowledge it discov- ers a heuristic possibility in its very negativity, in its capacity to strangeness.

Crucial for this approach to anachronism as an epistemological question is Didi-Huberman’s rereading of Walter Benjamin. If Benjamin tries to confront the historical discipline with the question of “origin,” this origin is not something that happened once and will never happen again, but a dynamics that potentially is present in every historical object: the unpredictable whirl or vortex that can appear at any moment in the river, an origin that does not denote the becoming of what is born, but the becoming of what is breeding in the becoming and in the decay. A history of art that raises the question of origin, in this sense, is a history of art attentive to the vortexes in the currents of styles, to the fissures and rifts in the foundations of the aesthetic doctrines, to the tears in the web of representation. This origin dialectically crystallizes the newness and the repetition, the survival and the rupture. It is above all, according to Didi-Huberman, an anachronism, surviving in the historical narrative as a crack, an accident, an anxiety, a formation of a symptom. An art history capable of inventing new “original objects” would thus be an art history capable of producing vortexes and fractures in the very knowledge that it assigns itself the task of engendering. This is what Didi-Huberman calls a capacity to create new “theoretical thresholds” in the discipline.

Rubbing history “against the grain” is Benjamin’s expression of the necessary dialectical movement in re-addressing the fundamental problem of historicity as such. For Benjamin, the challenge is to bring forth new models of temporality, models at the same time less idealistic and less trivial than the models in use in the historicism inherited from the 19th century. These new models would be based on the specific historic historicity in the artworks themselves, expressed in the intensive mode that multiplies connections between them. The image, according to Benjamin, produces a double-sided temporality. This is the famous and fugitive “dialectical image,” resisting any reduction to a simple historical document as well as, symmetrically, preventing the idealization of the artwork in a pure monument of the absolute.

It is well known that Benjamin, the philosophical junk dealer and the archaeologist of memory, early on made Aby Warburg’s motto his own: “der liebe Gott steckt im Detail,” “the good God hides in the details.” But this paradox of litter and detritus, of the unnoticed and very small, obtains a new dimension when one, with Didi-Huberman, notices its inherent over-determination, its opening force and complexity, practiced in the montage-character of the historical knowledge that Benjamin (as well as Warburg) produced. By means of montage, the “reified continuity of history” is blown up, scattered, as is the homogeneity of the epoch, in multidirectional series, rhizomes of ramifications where, for every object of the past, there occurs a collision between what Benjamin calls its “earlier history” and its “coming history.” The unconscious of the epoch arrives through its material traces and works: vestiges, counter-motives or counter-rhythms, falls or interruptions, symptoms or anxieties, syncopes or anachronisms in the continuity of the “facts of the past.” Confronted with this, the historian must abandon the old hierarchy of “important” and “unimportant” facts, and adopt the scrupulous gaze of the anthropologist paying attention to details, and above all to the smallest and most “impure” among these, exhibiting a “prehistory” of a culture. The humbleness of a material archaeology, the historian as a junk dealer of the memory in things, of the archive of singularities equals practical responses to the aporias of theory. This is the “Copernican turn” in Benjamin: it is no longer in the name of the eternal presence of the Idea, but rather in the presence of fragile survivals, mental or material, that the past is present. It is no longer the universal that is implemented in the particular, but the particular that, without any definitive synthesis, is distributed everywhere.

Knowledge by montage? Didi-Huberman theorizes montage and re-montage as a “paradigm” and a mode of knowledge consisting in remounting the path of the continuous heading for its accidences, ramifications, discontinuities. The image, he writes, dismantles history in the same way as one dismantles a watch, which is to say the same way as one scrupulously disjoints the pieces in a mechanism. In that moment culturally operative.

When he engraves the Greek word for memory over the entry to his library, Warburg indicates to the visitor that he enters the territory of another time. This other time bears the name Nachleben, the mysterious watchword for Warburg’s project: Nachleben der Antike. This is the “fundamental problem” whose materials his archive and library research projects try to assemble, in order to make it possible to understand the sedimentations and movements of the terrain. The theoretical and heuristic function of anthropology is here its capacity to deterritorialize knowledge by reintroducing difference in objects and anachronism in history. Warburg, who borrows — and displaces — the concept of “survival” from Edward B. Taylor, opens up the field of art history to anthropology not only in order to discover new objects of study for it, but also to open its time: the phantomal time of survivals (in 1928 Warburg defines the history of images that he practices as a “ghost story for truly adult people”). The present is woven by multiple pasts, and this is why, according to Taylor, the ethnologist must become the historian of each of his observations — Taylor, who, before Warburg and Freud, in the “trivial details” admires a capacity to make sense of their own insignificance.

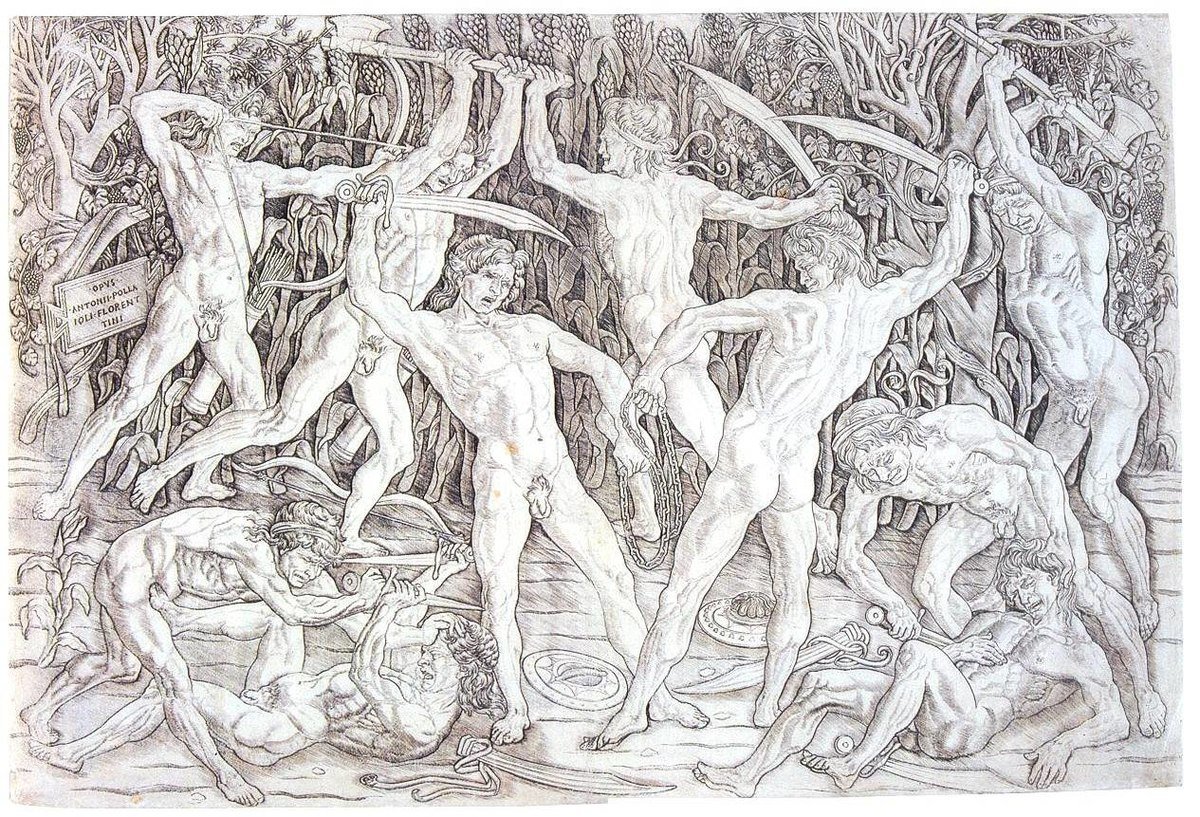

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, The Battle of the Nude Warriors, 1470-1480

The surviving form in Warburg, Didi- Huberman accentuates, is not triumphantly surviving the deaths of its rivals. On the contrary, as a symptom and a phantom, it survives its own death — having disappeared at one point in history; having reappeared a long time later at a moment when, maybe, one did not expect it any more; and having, consequently, survived in the ill-defined borderlands of a “collective memory.” Bricolaging his theory on the memory of forms, a theory constituted of jumps and latencies, survivals and anachronisms, desires and the unconscious, Warburg thus operates a decisive break with the very notions of historical “progress” and “development.” And like Burckhardt, he always refuses the synthesis, puts off the moment of conclusion, the Hegelian moment of absolute knowledge. This would be Warburg’s epistemological modesty: to take the consequences of the fact that an isolated researcher, a pioneer, cannot, must not, work on anything else than singularities. Modesty, but also courage: daring to travel as far as possible in this uncompleted analysis of singularities, discovering the extreme plasticity, the vertiginous capacity of transformation, in the time-image; a plasticity that imposes a new relation between the universal and the singular, a relation where the universal constantly would be able to transform under the pressure of, or impulse from, the local object. This is what Didi-Huberman calls Warburg’s “superior empiricism”: the close, analytic and philological attention to artworks as an occasion for inventing concepts, that is to say, for actively occupying the terrain of philosophy. This “superior empiricism” would also permit us to break with the negative judgments that the knowledge produced by Warburg is often submitted to: not a single coherent book, articles on microscopic questions, ideas that are too “big” and too movable, historical results that are as specialized as they are disseminated. This “bizarre” behavior is perhaps, in part, related to the mental struggles of “an (incurable) schizoid,” as Warburg himself described it in 1923. But, Didi-Huberman argues, it also originates from an epistemological choice that is remarkably well founded: the choice to transform, to remodel, the historical intelligibility of images under the pressure of each fecund singularity. This is why Warburgian knowledge is a plastic (and critical) knowledge par excellence, acting by interwoven memories and metamorphoses, intertwinings of knowledge and non-knowledge. His library and his incredible quantity of manuscripts, files, and documents constituted a plastic material capable of absorbing every accident, every unthinkable or unthought object of art history, and of transforming itself without ever fixating itself in an obtained result, a final knowledge. This is Warburg’s “theoretical non-limitation.”

Thus the “survival,” according to Warburg, offers no possibility to simplify history: being a transversal notion in relation to every chronological division, it imposes a terrific disorientation on every will to periodize. It imposes the paradox that the most ancient things sometimes come after the less ancient ones. Woven by long durations and critical moments, by ancient latencies and brutal resurgences, the survival anachronizes history. This is why we again need to confront the question of the symptom — this exception or intrusion, this disorientation of body and thought, this rupture of the “principle of individuation.” What is a symptom from the point of view of historical time? In this context it is, Didi-Huberman argues, the very particular rhythmicity of an event of survival: the mixture of an interruption (the sudden emergence of the Now) and a return (the sudden emergence of a Past), the unexpected compound of a contretemps and a repetition.

To speak like this is to recall the lesson of Nietzsche: genealogy as a symptomatology, implicating the necessity of thinking the symptom as something more than a strict discontinuity. Events of survival, critical points in the cycles of contretemps, these would be the movements and the temporalities of the symptom-image. During all his life Warburg tried to find a descriptive and theoretical concept for these movements. He called it Dynamogramm: the graph of the symptom-image, the impulsion of events of survival that are directly perceptible and transmissible thanks to the “seismographic” sensibility of the historian (the Warburg “seismograph” would be situated somewhere between Burckhardt and Nietzsche). Which, then, are the corporeal forms of the surviving time? The concept of Pathosformeln — the “pathos formulas,” the visible, physical, gestural, figural symptoms of a psychic time that is impossible to reduce to a simple web of rhetorical, sentimental or individual peripeteia — responds to this question. Pathosformeln and Dynamogramm seem to indicate that Warburg thought the image in a double regime, or according to the dialectical energy in a montage of things that in general are treated as contradictory: the pathos and the formula, the power and the graphic, the force and the form, the temporality of a subject and the spatiality of an object. It would be wrong, Didi-Huberman stresses, to say that the “great configurating energies” are “behind the works.” Warburg is an historian of singularities and not someone looking for abstract universalities. According to Warburg the “fundamental problems,” the forces, are directly in the forms, even if these are determined by or limited to miniscule singular objects.

In searching for traces of the Nachleben of classical postures and gestures in Renaissance art, traces that would shed light on the lasting power of certain Pathosformeln, Warburg attempts to create a kind of inventory of the psychic and corporeal states embodied in the works of figurative culture: a historical archive of intensities. Is there a typology for pathos formulas? In 1905, Warburg opens a large folio entitled “Schemata Pathosformeln,” presumably hoping to record in this register the typology in question. But most of the boxes are left blank: the project is a failure on the level of diagrams. Twenty years later, the atlas Mnemosyne, the constantly reworked, never finished montage of a considerable corpus of images, an unending body of work, will replace the Schemata Pathosformeln. Iconography can be organized by motifs, by types, but the pathos formulas encompass a field considered by Warburg to be rigorously trans-iconographic. In contrast to Charcot’s reductive charts, mastering the differences of the symptom in an iconography aiming for continuities, resemblances, and temporal uniformity, the montage in Mnemosyne respects the discontinuities and differences, never effaces the temporal hiatus between an archaeological drawing and a contemporary photograph, for example. Whereas Charcot always desires to bring the symptom back to its determination (see Didi-Huberman’s Invention de l’hystérie, 1982), the symptom in Warburg is an incessant and open work of the over-deter- mination. The symptom moves, displaces. The symptom only gives us access — immediately, intensely — to the organization of its own structural inaccessibility. The organization is a matter of removals and transfers, the “migrations” that Warburg made the destiny of the pathos formulas, and the moving geographies and historical survivals of which Mnemosyne, this cartographical application of a symptomatological observa- tion of culture, exactly tries to reconstitute.

Jean-Martin Charcot, Hysteria chronophotography, 1878

During the war Warburg spends all his energies collecting, collating and collaging disparate information on the causes of the conflict. In this process, he comes to believe that he himself is the cause of the war, having aroused the wrath of the pagan deities through his art historical scholarship. This, in combination with paranoia about his position as a high profile, wealthy Jew during a time of massively increasing anti-Semitism, provokes his collapse into psychosis in 1918. After a couple of years in various psychiatric institutions he ends up in the Bellevue sanatorium in Kreuzlingen (where he stays between 1921 and 1924), directed by Ludwig Binswanger, the nephew of Otto Ludwig Binswanger, to whom the mad Nietzsche was entrusted. Nietzsche is Warburg’s starting point when he elaborates his “epistemological break” in the field of aesthetics in order to move away from Kant, Lessing, and Winckelmann. But Nietzsche is not enough for Warburg, whose vocabulary, Didi-Huberman points out, is closer to psychopathology as practiced by Freud or Binswanger (and, when he speaks of culture in terms of schizophrenia, to the thinking of Deleuze).

Foucault shows how a history of madness can produce an archaeology of knowledge. In the destructive forces of his own psychic trial Warburg arrives to find the conditions of a renewal and intensifying of his entire research. The psychotherapy of Binswanger describes this anamnesis and this dialectical reversal: it is necessary to make Warburg understand his trial as an experience that is not a pure privation or dysfunctionality. This displacement is crucial: the symptom is no longer to be considered as a simple sign of disorder or ill health, but as a structure of a fundamental experience, not as a lack to correct, but as the expression of a total function. This is knowledge by involvement, an implicated, entangled knowledge, managing at the same time knowledge and non-knowledge, meaning and non-meaning, construction and destruction — a knowledge that constitutes a radical break with the positivism of the medical semiologies, in which the notion of the symptom always had been brought back to the “sign” of the illness or disorder.

How to expose an extreme entanglement of connections? How to find a form that is rigorous (that is, theoretically founded) and non-schematic (that is, non-reducing, capable of respecting every singularity)? Mnemosyne, the atlas of images that Warburg tirelessly works on after his return from Kreuzlingen and until his death, is, according to Didi-Huberman, such a form of exposition. There are no reducing operations or reductive functions in Warburg’s work. Ernst Cassirer’s big mistake is probably, Didi-Huberman argues, to think the symbolical forms according to the implicit model of an exact knowledge. The “non-knowledge,” the unconscious knowledge, does only have a negative place in it, absent or revoked. Cassirer, even if he admires Warburg, hypostasizes the direction of history by establishing an order that shows all the signs of Hegelian teleology. Philosophie der symbolischen Formen plays an analogous role in relation to Warburg’s manuscripts or Mnemosyne as Hegel’s Enzyklopädie der philosophischen Wissenschaften in relation to Novalis’s Das Allgemeine Brouillon, where it is not the unity of every domain, but the circulation of connections between them that matters.

Mnemosyne is, above all, a photographic dispositif (even if, as Didi-Huberman stresses, the visual part of the project was supposed to be accompanied by at least two volumes of writings). The photographs from Warburg’s huge collection were attached to big black panels (150 cm x 200 cm) by means of clips that made them easy to regroup, rearrange in a perpetual combinatory displacement from one panel to another, with all sorts of serial effects or effects of contrast. Mnemosyne, thus, presents itself as a dispositif destined to maintain the entanglements, to manifest the over-determinations at work in the history of images, making it possible to compare at a glance, on one single panel, ten, twenty, or thirty images; making it possible to expose the entire archive. Not only in order to recapitulate Warburg’s work, but in order to unfold it in every possible direction or to discover still unnoticed possibilities.

The knowledge that resulted from this experimental record was radically new in the field of human sciences. It was necessary for Warburg to invent a new form of collecting and showing, a form that was neither bringing things together under the authority of a principle of totalizing reason, nor bringing together the most different things possible under the non-authority of the arbitrary. It was necessary to show that the fluxes only consist of tensions, that the assembled packages of images were to explode, but also that the differences sketch out configurations and that the divergences together create unnoticed orders of coherence: what Didi-Huberman calls montage. Warburg would be creating a new epistemic configuration — a knowledge by montage related to Benjamin’s in the Passagen-Werk, but also, in some aspects, to Bataille’s montage of repulsions or Eisenstein’s montage of attractions — starting from an observation on Nachleben itself: the images that are carrying survivals are no other than montages of heterogeneous meanings and temporalities.

Didi-Huberman is not the first to stress an affinity between Mnemosyne and some of its more or less contemporary avant-garde experiences, such as collage, photomontage, and film montage (cf. William Heckscher, Martin Warnke, Werner Hofmann, Kurt Forster, Giorgio Agamben, Philippe-Alain Michaud…). But such associations have also found their critics. In “Gerhard Richter’s Atlas: The Anomic Archive” (October #88, 1999), Benjamin Buchloh states that Mnemosyne, as based on “a model of historical memory and continuity of experience,” would be opposed to the models of modernity “as providing instantaneous presence, shock, and perceptual rupture.” In reality, though, Didi- Huberman, points out, Buchloh here seems to content himself with extending the common confusion of survival and continuity of tradition, and of memory and memory of things passed; he is unable to imagine that the action of memory presupposes the involvement (this would be the theoretical lesson of the symptom) with everything between which he wants to establish an opposition: “shock” and “historical memory,” “rupture” and “historical transmission.” The fact that Warburg’s atlas is about the memory function of images in the Western culture does not imply that it would not invent something as radical, “shocking” and inopportune as a surrealist montage in Documents. Mnemosyne, then, according to Didi-Huberman, is an avant-garde object in its own way. Not by breaking with the past, which it does not stop to become involved in, but by breaking with a certain mode of thinking the past. Warburg’s rupture consists exactly in the thought of time itself as a montage of heterogeneous elements.

Thoughts are exempted from customs duty, Warburg writes. And only montage, as a form of thinking, makes it possible to spatialize the deterritorializations of the objects of knowledge. Mnemosyne would be an avant-garde object by daring to deconstruct the historical souvenir album of the influences from classical antiquity and replacing it with an erratic memory atlas, deregulated in relation to the unconscious, saturated with heterogeneous images, submerged by anachronistic or archaic elements, haunted by empty places, missing links, gaps in one’s memory.

What does a montage consist of, what are its elements? Warburg often speaks in terms of “details.” Details: small, unrecognized things, like the discrete motifs that are lost in the grisaille of the fresco, the backside of an unknown medal or the modest pedestal of a statue. Here we find Warburg’s most famous motto again: “the good God hides in the details.” According to Dieter Wuttke, its direct reference would be a philological dictum by Hermann Usener: “it is in the smallest things that the greatest forces reside.” In reality it would be possible to construct an entire tradition haunted by the image of mundus in gutta and by the problem of a truth hidden in everything, even in the most humble. In Leibniz, for example, the details become a theoretical motif as the “small perceptions.” But, as Didi-Huberman further reminds us, the detail has no intrinsic epistemological value: everything depends upon what you expect from it and the manipulation that you subject it to (Gaston Bachelard, in his Essai sur la connaissance approchée, 1927, described the epistemological status of the detail as that of a division, a disjunction of the subject of science, of an “intimate conflict that it can never wholly pacify”). In order to understand Warburg’s motto, it would thus be necessary to investigate the use values of the detail in Mnemosyne.

In Warburg, the detail, according to Didi-Huberman, is neither a simple index of identity, nor a semeion, nor an iconological “key” that would permit the revelation of a hidden signification of the images. In Warburg, the detail is always also a symptom. Identity is not the goal of his interpretation; the detail is understood on the basis of its effects of intrusion or exception: its historical singularity. This singularity, this rift in the present time, is in its own turn understood as the index of a structure of survival, which presupposes that one regulates oneself on the powers of the unconscious. As in Freud, the detail in Warburg reveals itself in the discards of the observation: it is a detail by displacement, not a detail by enlargement or magnification. Warburg’s model is “pathic” or “psychopathic” — a way of saying that the detail does indeed concern the movements or the displacements of a desire that does not reveal its name: less a “meticulous consciousness,” then, than a sly unconsciousness that always arrives to locate itself where you did not look for it. Warburg’s detail brings us neither the omnivoyance nor the omniscience that positivists hoped for. The details are only significant if they are bearers of uncertainty, non-knowledge, disorientation. (In Devant l’image, Didi-Huberman differentiates the detail — considered as a semiotic object tending towards stability and closure, as presupposing a logic of identity — from the pan — considered as something semiotically labile and open, only revealing figurability itself: a process, a power, a not-yet, a “quasi”-existence of the figure.)

Didi-Huberman calls attention to the fact that Warburg’s motto “the good God hides in the details” is written next to another one that concerns the question of non-knowledge: “We are trying to find our own ignorance, and where we find it, we fight it.” Why, incessantly, try to find this element of non-knowledge that we are fighting? Why not restrict ourselves to knowing, like every scientist is supposed to? Warburg obtained his response from his own psychoanalytical experience in Kreuzlingen: the non-knowledge bears the trace of that which is the most essential, but also the most combated, the most repressed, or foreclosed, in ourselves, or in our culture. The detail, in that sense, is that which can produce this paradoxical knowledge: a knowledge woven by non-knowledge, incapable of constituting its object without being involved or entangled in it.

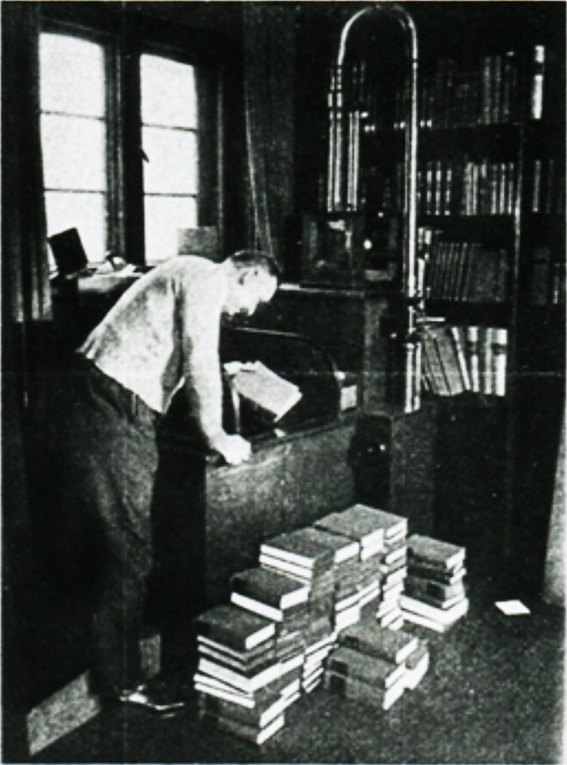

Fritz Saxl in the Biblioteca Warburg in London.

This symptomatological acceptation of the detail does, at all events, offer a way to better understand the strangely non-iconographic structure of Mnemosyne, this rhizomatic comparativism that is less interested in the identification of motifs and their historical laws of evolution, than in their contamination and temporal laws of survival. Mnemosyne shows how Warburg, by shattering the iconographic guardrail, from the very beginning displaces every ambition of the iconology whose paternity one nevertheless attributes to him. “Iconology” is indeed not the name of the “nameless science” that Warburg hoped for. His own disciples, and above all Saxl and Panofsky, reduces it to the job of deciphering figurative allegories. Panofsky’s magisterial iconology in fact discharges itself from all the great challenges that Warburg’s work contains. Panofsky wants to define the “meaning” of the images where Warburg tried to catch their very “life,” their paradoxical “survival.” Panofsky wants to interpret the contents and the figurative “themes” beyond their expression, where Warburg tried to understand the “expressive value” of the images even beyond their meaning. Panofsky wants to reduce the particular symptoms to symbols that would encompass them structurally, whereas Warburg had engaged in an inverse path, trying to reveal, in the apparent unity of symbols, the structural schize of the symptoms. Panofsky wants to start from Kant and engage in a knowledge-conquest with a quantity of acquired results. Warburg, on the contrary, started from Nietzsche in order to let his work bear witness to the excessive pain in his thinking, to the place that the non-knowledge and the empathy occupies in it, to the impressive quantity of questions without answers that it raises.

In Mnemosyne iconographies are indeterminate. This is why Warburg characterizes the particularity of his iconology as an “iconology of intervals” (Ikonologie des Zwischenraumes). The intervals are the epistemological instruments of disciplinary deterritorialization par excellence in Warburg, and first of all they manifest themselves in the borders that separate the photographs from each other in Mnemosyne: vacant zones of black cloth. These zones offer a “background,” a “medium,” but also a “passage” between the photographs. They offer to the montage its space of work: every “detail” is separated from the other by a black “interval,” sketching out, in a negative way, the visual structure of the montage as such. But every “detail” is itself reframed so as to include the whole system of “intervals” that organize the dispositif of the representation. Every “detail” of Mnemosyne could without any doubt, Didi-Huberman asserts, be analyzed in relation to the network of “intervals” produced by its own framing. It would then be possible to say that for Warburg “the good God hides in the interval.” In fact, Warburg would seem to anticipate an idea that is essential for Benjamin, according to whom “it is precisely in the very small details of the intermediary that the eternally identical manifests itself.” At the same time Warburg would anticipate the project of a structural analysis of singularities: the detail has only an importance as a singularity, that is, as a hinge, a pivot — namely the interval that makes it possible to effectuate a passage — between orders of heterogeneous realities which one nevertheless has to mount together.

Jonas (J) Magnusson is is an author, translator, and editor-in-chief of OEI