Confronting Fra Angelico

Daniel Pedersen

In the beginning of Georges Didi-Huberman’s Confronting Images (Devant l’image), published the same year as Fra Angelico: Dissemblance and Figuration (Fra Angelico. Dissemblance et figuration), the following question is posed: how has art history traditionally dealt with a certain “image of art”? From this starting point, an attempt is made to radically change our common preconceptions and expectations of art history as a specific knowledge and academic discipline.

The aim of this text is not to assess Didi- Huberman’s critique of art history as a discipline as such, but to see how he uses an alternative epistemological framework in dealing with the 15th century Italian painter Fra Angelico, and specifically his frescoes in the San Marco convent. The following text contains three main themes. Firstly the epistemological problem will be situated and defined, secondly the scriptural background will be approached in order to penetrate into Fra Angelico’s lived universe, and thirdly some specific problems, such as the annunciation and incarnation, will be addressed as well as the key concepts that Didi-Huberman brings out of the scholastic tradition. These will serve as reference points for an alternative way of encountering the frescoes. The underlining problem, however, is how to encounter the frescoes. Which methodological tools did Didi- Huberman deploy when engaging with Christian art in general, and Fra Angelico’s frescoes in particular? Didi-Huberman’s own fear of the stakes involved is worth quoting:

Paintings are often disconcerting. They present our gaze with colors and obvious or simple forms — but often color and forms we were not expecting. No less often, unfortunately, we choose to close our eyes to the obvious, when this obviousness is there to disconcert us. We close our eyes to the surprises offered the gaze: we arm ourselves in advance with categories that decide for us what to see and what not to see, where to see and where to avoid looking.1

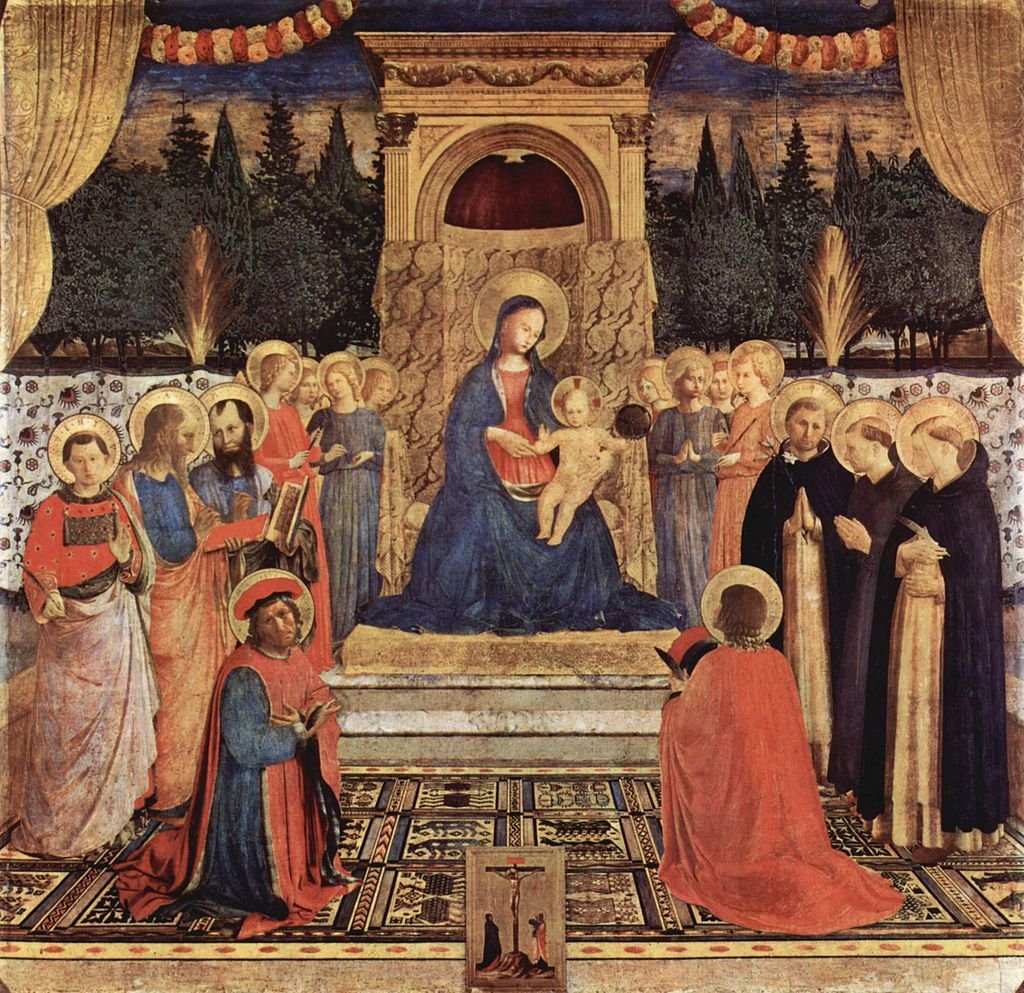

Fra Angelico, San Marco Altarpiece, 1438-1443

One traditional way to read Christian art is to identify the passage in the Bible being “illustrated.” This presupposes causality in art history: the figures in the painting are identified and the gestures are codified. By identifying the motif being transformed, which takes us from Panofsky’s first meaning, the pre-iconographical, to a figure (figura), i.e., to the secondary meaning, or the iconographical, we end up with the biblical story. Thus, by grasping the story we likewise believe that we have grasped the subject of the work of art. Such a reading commits to what we could call the naturalistic fallacy, in that it does not account for the fact that religious art is always already a part of a living liturgical practice, and hence it risks misunderstanding religious art as mere illustrations of biblical stories. The act of freeing oneself from this fallacy of the traditional — or rather Panofskian — art historian, nevertheless risks leaving the spectator in a void, bereft of all traditional categories. Rather than entertaining a notion of the encumbered self, it is important to see how the possibility of relating to the artwork in a different way is possible only on account of constructing an alternative grounding. What is then Didi-Huberman’s suggestion? Does he in fact claim that we do not need any form of grounding at all? It is obvious that Didi-Huberman is not proposing that any other system would serve us just as well. The confrontation with a traditional epistemology of art is intended to bring forth all the aspects to which the spectator has previously been blind. In doing so Didi-Huberman proposes that the spectator should enter into the painting’s living history in an almost philological way and break with the view that the “image of art” is some- thing dead on the wall, ready to be dissected by the master surgeon himself: the art historian, or rather the Art historian.

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematism No. 38, 1916

But how should we begin? The challenge is to connect to the pictorial enigma — the enigma of pictorial matter — only to refer it back to the mystery from which it drew its most profound and peculiar necessity. We should not fixate on an image of art and seal it by identifying its subject. This is a critique that, in a secular vein, can be found in Malevich: the modernist who wants to bring back the subject matter into painting performs a (pseudo-) resacralizing of color. In one of his essays on art Malevich writes: “Color and texture in painting are ends in themselves. They are the essence of painting, but this essence has always been destroyed by the subject.”2 Even if it is not possible to attribute these thoughts in toto to Didi-Huberman’s essay, Malevich’s critique of the priority given to subject over color and texture finds a resonance in Didi-Huberman’s claim that the very essence of religious paintings, supposed to be reincarnated and transmitted to the spectator, ultimately will be lost if one does not try to go beyond an understanding of them as mere representations. For Didi-Huberman, it is only by dwelling on the dissemblance that the gaze can gain access to the incarnated world beyond the fresco on the wall.3

The book Fra Angelico has, as the title suggests, two main parts: dissemblance and figuration. In medieval theology dissimilitudo was the non-resemblance between the phenomenal and the divine. How then does Didi-Huberman go about examining dissemblance? In order to flesh out this aspect he probes deep into the scholastic world of the Late Middle Ages. The process of reaching deeper in the Scripture and the dimension of the mystical can only be fulfilled by delving into its sources, the very world in which Fra Angelico lived and worked. So when Didi-Huberman walks through the convent in San Marco he is both walking through the very same corridors as the 15th century painter, and trying to recreate the spiritual world in which Fra Angelico existed. In order to succeed in this he has to revive the scholastic tradition. The admirable depths [mira profunditas] can be reached by the act of dividing. “The letter killeth but the spirit giveth life,” writes Saint Paul.4 But, as Didi-Huberman writes: “In medieval exegesis, the technical name for the front side — the letter, the surface — is historia” (Fra Angelico 38). Historia is just a surface, and in order to reach the biblical depths behind this surface we must gain intimacy with the biblical world in which the paintings were meant to act. The question being posed relates not only to what is visible in the painting, but also to what is not visible, or what is present and not visible and only implied in the painting. In the scholastic world in which Fra Angelico lived dissemblance was a living relationship, a dialectical process of which the spectator was conscious at all times.

Didi-Huberman writes that “the figure demands and presupposes the totality of Christian time” (Fra Angelico 38). In an analogy to the idea that the figure embodies its own time and mystery, something that cannot be perceived from outside, it also embodies a truth (veritas) that goes beyond it. This “outside” is the allegory, a rhetorical figure common during the Middle Ages and a foundation for understanding not only the Scriptures but also the classical Greek and Latin heritage. By understanding the marble allegorically we could sum up the life of Christ from the uterus Mariae to the crucifixion, from the virginal birth to his resurrection, in its red “incarnated” color and material.5 Christ is a rock, the foundation of the church, and Gabriel’s red clothing during the Annunciation. The figure opens up a path that connects different parts of the theological and scholastic universes.

Fra Angelico, Annunciation, San Marco, Cell 3, 1440-42

We should not forget that. according to the Scripture, the first act that involved God and the human was the creative act with which God gave life to dust and created man. This is both a sculptural act and an act in which the very material (dust) is assigned a double meaning: when given life it is no longer what it was, but something else. There is an analogous way of thinking in relation to the Medieval paintings, in which the image was to incarnate the very mystery it was supposed to depict, as with Annunciation. The different parts of the portrait were not to be seen as mere points of reference for scholars of the Scripture, but as a passage into the biblical mystery. The image itself was to reincarnate not merely the biblical stories, but also the scriptural truth and its mystery. At least this ambition can be found in the scholastic writings. In his interpretation of the “figurative,” Dionysius the Areopagite proposed that the figure served “as a mean of constituting the image between body and mystery: the paradoxical path of dissemblant similitudes — we could say the path of the uncanniness of form — figures that are not valued for what they represent visibly, but for what they show visually, beyond their aspect, as indexes of the mystery” (Fra Angelico 6f ). A problem in the Christian tradition is how to understand the complexity of God as superessential, and the consequences this yields for the image. In every aspect, God’s qualities go beyond what the painter can fix on the wall or the canvas. Didi-Huberman writes: “the image as such did not define an aspect, and still less a story; it was concentrated at the highest level of the soul, exactly where it could demonstrate its ‘aptitude for knowing and loving God.’ Everywhere else, the image was broken, its fragments disseminated or diffused in a ‘nonspecific’ resemblance” (Fra Angelico 6f ). Contemplating the frescoes requires going back to what is considered the first act of art in the Christian tradition: the very creation of the world. This has to do with the fact that Creation itself is the first and only example of something not already in the world being created.

Today one can understand art as the creation of something new or as copying something already existing, which is to be compared to the Socratic critique of art as the mere copying of a copy. However, when it comes to Annunciation there is not only the problem of copying a copy, but also of rendering an event that was analogous to a creation for which there were no natural analogy. One is trying to depict something that is not possible to depict: a divine intervention. This the paradox. Thomas Aquinas writes:

Even though there is some degree of resemblance to God [aliqualis Dei similitudo] in all creatures, it is only within the creature endowed with reason that the resemblance to God is in the form of an image [imago]; in all other creatures, it is in the form of the vestige [similitudo vestigii]… The reason for this can be clearly understood if we observe the respective means through which the image and the vestige constitute a representation [modus quo repraesentat vestigium, et quo repraesentat imago]. For the image, as we have said, represents according to a specific resemblance, whereas the vestige represents in the way an effect represents its cause without attaining a specific resemblance, just as we call the prints [impressiones] left by animals’ movements vestiges, or as ash are called vestiges of the fire, or the desolation of a country is called the vestiges of the enemy army (Summa Theologica, Ia, 93, 6, quoted in Fra Angelico 38).

To God, man is like an image. When Christ was born as a man he was born as an image of his father, but not so different from other men that he could be perceived as radically different.

The power of the image lies not so much in its power of representing as in disrupting “the order of representation” (Fra Angelico 41). The resemblance of images is supposed to function as the dissimilarity [defiguratio] that the mystery imposes. The basic difference is the one between the naive and the theological spectator. The first might see the picture as equivalent to a window through which one can see the world, while the latter can distinguish between two forms of imitation: the one that lies and the one that tells the truth. Didi-Huberman calls the latter “the figural imitation.” His own example is a painting of a young bearded man, which from a naive point of view can be seen as “the representation of Christ” due to the simple fact that this young man looks like the Son of the Virgin. But in the Christian (theological) tradition, the shapeless rock that, according to the Old Testament, gave water to the thirsting Israelites, is a “living figura Christi,” although it has no visible resemblance to Christ. In this sense it is also useful to reconnect this to the earlier discussion on man as created in the image of God, and to the fact that Adam’s original sin has distorted man’s resemblance with God. Man himself is forced, even condemned, to live in a state of dissimilarity. When painting Christ one must paint Christ as a “Word became flesh,” but at the same time, one must be aware that picturing God as a man is picturing God as the wounded resemblance to God, i.e. man. The paradox is to paint Christ as similar to man and yet so different that he is differentiated from man; this difference (one should really see this as a différance par excellence) is simple a way to point towards the mystery, incarnate the mystery, since God himself is superessential and impossible to depict. To put it in Spinoza’s terms: it is the problem of grasping a mode of the attribute, but in doing this still retaining a mystical remainder that transgresses the attribute, whereupon this mystical instantiation is there to point towards substance.

Before we go deeper into the question of the human image and incarnation, let us first pursue the path of the mystery of the image. This mystery is only possible to understand if we first enter into the specific scriptural meaning of the different passages that serve as material for the frescoes. One of the most powerful examples of the failure of the traditional representational approach that Didi-Huberman provides, is the painting of the Holy Conversation [Madonna of the Shadows], in the east corridor of the San Marco onvent, where art historians often have ignored half of the painting. The lower part of the painting, the painted marble, has not been treated as a part of the painting, and in many reproductions of Fra Angelico’s work it has simply been omitted. This is not only exemplary of how art history makes choices about what to include, but also of a flagrant lack of knowledge of the lived world in a Dominican convent. Hence a part of the painting has often been excluded simply because it does not fit into already existing categories. This, however, has perversely enough been seen as a problem for the painting and not for the epistemology of art history. There is, according to Didi-Huberman, a dialectical relationship between memory and imagination, and marble can be seen as memory’s material par excellence. The painting is one figurative gesture consisting of both marble and canvas. By closely examining the marble both as a material and as a means of transcendence, Didi-Huberman shows how the essence of the biblical story is incarnated in the painting.

Here we have an example where the word incarnation itself deserves close attention — incarnatio as the very place and act when something is being “embodied in flesh.” Didi-Huberman wants to restore the world of experience in the convent, which is what gives life to the painting. Here there is a double bind: the mystery itself and the memory of the mystery. The scholastic thinking was indeed meant to bring preciseness and accuracy to the human understanding of the Scriptures. The marble aims to exhibit another visuality. Against this background it is possible to see how Fra Angelico deals with an aesthetic of limitation, which prescribes that it is only possible to paint certain human aspects of God’s being. God is superessential, He is beyond qualities, and therefore his divinity can only be hinted at, never fully captured. Could the marble be such an attempt to grasp and transmit this experience? Didi- Huberman discusses this by closely examining one specific painting, whose richness the traditional art historian’s approach fails to grasp: the Annunciation painted in the third cell in the San Marco convent.

Because of the work’s horizontal line the viewer of the Annunciation is forced to kneel in order to assume the right position. This is the Scripture at work, not only as an illustration, but a re-embodiment (incarnation) of the Word. The eye that meets Annunciation will have to meet the eyes of the Virgin. Exegesis accounts for a web of references that makes the spectator not only gaze at Mary with the angel’s eyes, but also look at the divine (the angel) with Mary’s eyes. To think the Virgin with one’s eyes is also to have Mary lend her gaze and contemplation to whoever is kneeling and believing in front of her. This lending is what the theologians would call mediation. It is the Maria mediatrix that goes back to Albert Magnus and the Dominican scholastic tradition. In Magnus’s writings mediation means reconciliation. Mary reconciles with her calling, to be chosen as the mother of God, but before that we have the mediation of Christ himself, who will have to sacrifice himself to reconcile man with God.Mary is situated where the “extremes of time” and “extremes of places” intersect (Fra Angelico 225). She is in a closed (virginal) garden (hortus conclusus) that brings the Garden of Creation together with Paradise. The time present in the garden is “at the same time” actual lived time, and the descent into the garden is a descent into life, where the monks have Mary present in their own garden. Maria templum will watch over you, to the extent that the material of the garden will encapsulate even the cell; the convent will be part of a great Marian body. It is not only the figure or the ground (the Ādām, in Hebrew dust/soil) in the Garden that carries memory. Man was created from dust and the Word gave life. They — dust and Word — are the common ground of Christ and man, a ground in which the Word was rooted, just as in the story by Jacobus de Voragine, as cited by Didi- Huberman:

A rich and noble soldier, abandoning the ways of the world, entered the Cistercian order; and because he did not know his letters, the monks, not daring to send back to the lay people such a noble individual, gave him a master to see if by chance he could learn something and, in this way, stay among them. But having received quite a long time lessons from his master, he could learn absolutely nothing, except these two words: Ave Maria. He held them with such love that everywhere he went, and in everything he did, at every moment he would ruminate on these words. Finally, he died and was buried with the other monks in the cemetery: and it came to pass that on his grave grew up a magnificent lily and on each leaf these words were written in letters of gold: Ave Maria. Everyone hastened to contemplate such a great miracle. They removed the earth from the grave and found that the root of the lily began in the mouth of the deceased (Fra Angelico 226f ).

The only words the idiot knew were Ave Maria, but that was enough to save him: such is the power of the Virgin to the kneeling monk. In order to understand the image we must consider such stories and believe that the monks found them to be literally true. The mystery was such that the Word could give life and the Name was likewise miraculous. When uttering “Ave Maria” you were not alone. In retelling Jacobus de Voragines’ story, we must also consider the corporeal dimension of the Word and its possibility to become materialized. There is a dialectic of the corporeal dimension, the room for contemplation, the Scripture, and the scholastic universe, and in facing the image we must try to move freely between them. A further analogy between the painted matter and the biblical flesh is that the divine nature of the Son joined, but did not mix, with human nature. Christ is at the same time divine and human. This relationship is present in the images where they are said to capture one aspect of the divine mystery, but in no way do they contain a part of the mystery itself. It exists as a relation. This means that the frescoes have the pedagogical function of recreating the Incarnation they depict. One could argue that the coexistence of man and divinity has its counterpart in the depiction of the Incarnation and the revealing of the mystery.

The aim of Christian art is the resemblance with a beyond — the desire (desiderium) for something that does not exist in this world, a Jenseitssehnsucht. But in the picture a transformation occurs when the figure reaches beyond natural resemblance toward the supernatural (perhaps glimpsing the superessential).6 This act of willing, which is also a form of love, is desire. The color in Fra Angelico’s fresco (the pictorial marble) is in one way the pure formulation of a “mystical desiderium.”7 And Didi-Huberman adds: “no figure will ever let itself be recognized by its true face” (The Power of the Figure 39). The real truth (virtus) of the figure is not and cannot be expressed, it acts virtually within it. This virtuality of painting is expressed in the power of color. Color is not only in one place, and here we might compare this with the red dots on the flowers and of Christ’s stigma in Fra Angelico’s The Crucifixion, the wound as transposed into nature, because it should have the capacity to pass from one place to another. Once again, we could go back to the red marble and its virtuality, and the power to find a specific point through which both the scriptural mystery and story can be exposed, as described above with the summary of Christ’s life. Didi-Huberman also takes Christ’s blood as an example of something that can become a network of “fluencies”. He concludes: “The entire figure has virtualized the event it celebrates, and in the use of color it has transformed the virtual into a real visual power” (The Power of the Figure 40).

Fra Angelico, The Crucifixion, 1420-1423

There is always an act of displacement (translatio) in Christian paintings. The first commandment of the figure could, according to Didi-Huberman, be called translatio (The Power of the Figure 33). In every crucifixion there is a displacement of time that prevents us from fully fixing our attention on the event being portrayed. The wood of the cross can also tell us of the life lost in Paradise, and the skull, often painted in the foreground,8 reminds us not only of death as “invented” by Adam, when driven out of Paradise, but also of Christ murdered by the crowd and himself killing the “sinner” in man, as the new Adam. There is always translatio, multiple layers of displacement. The translatio is therefore another way of seeing art and a different practice of reading art works not reducible to (simple) narrative sequences. It changes the historical causality that is otherwise being forced upon the spectator. The image must not only, through dissemblance, reveal its own as well as the scriptural mysteries to the spectator, but also reveal a divine presence. Christ’s figure in the communion is its presence (praesentatio): it is the body and blood of Christ being consumed. The Christian image demands the spectator to believe, trust and imagine the existence of impossible spaces, as when Word becomes flesh. The space produced by the figure operates by “putting two heterogeneous objects in one place” (The Power of the Figure 46). This contradiction can be seen as the mystery of the incarnation which by necessity also must be spatially situated, but wherein the mystery always lies beyond the mere visuality of the image. In order to construct another space one must have the natural space in mind, as if the mystical and divine space could only be recognized in relation to the room in which the paintings are viewed. What is happening with the Virgin is only possible to know through the scriptures and whatever she discloses with her solemn facial expression. The figure is the place of “the power of the place,” the place where the divine and human is gathered in one single body. The Virgin Mary is not present in the image only as a figure put in a place, but as the “mutual inclusion of place” (ibid). Didi-Huberman elaborates: “As if interior and exterior covered each other, as if the entire space of the mystery could nestle in the womb of Mary herself ” (ibid). The figure in Annunciation should therefore not be seen as being in a place, but rather as the place itself. The Virgin Mary is the result of the impossible space where the divine and the human coexist. The power of the place (collocatio) and the power of the name (nominatio) are closely linked. In the beginning God said “Let there be light: and there was light.” God’s word is a creation by means of a first division: the heavens and the earth created separately, a division between light and darkness. In Annunciation the Word marries the divine and the human. The divine name fits into the divine word. The Word became flesh and uttered the divine name Mary — brings forth her presence. They are never far away. The exegetical practice uses many different techniques to work the figural meaning around the name. The name has the power (nominatio) to generate the place where faith can unravel at least one aspect of the divine mystery.

Let’s return to the milieu in which the paintings were present, in order to excavate not only its material and historical aspects, but also the imaginary universe in which the monks acted. To understand this, if it is at all hermeneutically possible, we must understand the way in which the medieval monks interacted bodily with the space. One telling example of how perspective is everything, and how it alters the viewer’s visual experience, is Andrea Pozzo’s trompe-l’œil in the Sant-Ignazio dome in Rome (1685), which demands that the spectator should assume one fixed place if he is to fully see the perfect perspectives of the paintings. This is an example of how paintings affect the bodily presence in the church by demanding fixation in one particular place. Everything, both the perspectives and what they depict, is twisted and changed when we leave the “place of pure seeing.”9 It would be possible to argue something similar in relation to Fra Angelico’s frescoes, although this is in no way makes then comparable to Pozzo. In Annunciation the horizontal line is raised as if it would force the viewers to their knees to see the fresco as it is supposed to be perceived.10 This, however, results in some very interesting consequences. First, it reproduces the liturgical posture of Ave Maria (and her own humbleness in her task), and second, the posture puts the monks in a position that makes them look up towards the picture, hence assuming their place in the theological hierarchy. The act of piety when kneeling in front of the image is forced upon us, since we can only see the work properly if we have assumed this position; and since it is the position of the believer, it follows that we can only see the miracle — the incarnation, Word becoming flesh — if we believe and enter into the theological universe. To this we could add that the latter method also characterizes Didi-Huberman’s method — which can be taken both as a critique and an appreciation.

Andrea Pozzo's painted ceiling in the Church of St. Ignazio, 1685–1694

The convent itself is a place of spiritual work, a place of commemoration of the Creator, and the frescoes cannot go against this purpose. It is a sanctified place, and the liturgical function that brings the spectator to her knees is also supposed to make her remember. It is the place for the soul to remember.11 The place of remembrance becomes especially important if we recall the Thomasian doctrine that the art of memory, i.e. to remember not only the biblical time or the Incarnation, was founded upon the principle that we do not remember through time, but rather through place. Didi-Huberman quotes Albertus Magnus:

Since it is self-evident that the time for everything we must remember is past time, it is therefore not time that can distinguish between the things to be remembered: for time does not lead us to one thing rather than another. The place, on the contrary, especially if it is solemn [or sanctified, solemnis] distinguishes between these things, since there is not only one place to remember all of them, and its power increases [movet] to the degree that the place is solemn and rare. In fact, the soul adheres [inhaeret] more firmly to solemn and rare things; and that is why they are more firmly imprinted [imprimuntur] and move us [movent] more deeply.12

Albertus Magnus identifies three criteria for a place of memory, all of which can be connected to the complex functions of collectio and identified in Fra Angelico’s convent frescoes. The first has to do with the image itself, i.e. that the place does not emerge from a simple position. Didi-Huberman exemplifies this with the Virgin’s house, which was not built in a garden, but from “the arrangement of places and images” (De bono 477, Fra Angelico 175) [dispositio locorum et imaginum] that recalls the “as if ”construction in the garden of Paradise. Once again we are faced with the biblical story that Christ resurrected humanity and retrieved the possibility for man to enter into Paradise. Secondly, the place of memory is not a natural place, but is constructed within the soul by the soul to “conserve the image” [sibi facit anima ad reservationem imaginis] (Fra Angelico 175). The goal is not to accurately describe the situation pictorially but to make the transition in temporality through a play of associations. Thirdly, this is the proof according to Albert Magnus, namely that the place of memory cannot be attributed to one particular event (but to the place). Rather, images perturbate and distort each other through their dissemination in the human soul “as waves in water interfere with one another when they are great in number” (De bono 477, 479; Fra Angelico 175).

Daniel Pedersen is an author and has translated Didi-Huberman’s Écorces to Swedish

Notes

1. Georges Didi-Huberman, Fra Angelico: Dissemblance and Figuration. Trans. Jane Marie Todd (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995), 1. Henceforth cited as Fra Angelico with page number.

2. Kazimir Malevich, “From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism,” in K. S. Malevich, Essays on Art, 1915–1928, Vol. I, trans. and ed. Troels Andersen (Copenhagen, 1968), 25.

3. The question of opening up images has been a central part of Didi-Huberman’s project and his critique of the traditional epistemology of art history. One of his later books, L’image ouverte (Paris: Gallimard, 2007), is devoted to incarnation in the visual arts. Another work on “opening,” which deals with the theme in a very physical way, is Ouvrir Vénus: Nudité, rêve, cruauté (Paris: Gallimard, 1999).

4. 2 Cor. 3:6.

5. It should be noted that Didi-Huberman explicitly makes the argument with reference to Giotto’s allegorical paintings in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, but I would argue that the allegorical reading is applicable to Fra Angelico’s frescoes in the San Marco Convent as well.

6. Cf. the statement by Thomas Aquinas: “Est quaedam operatio animae in homine quae dividendo et componendo format diversas rerum imagines, etiam quae non sunt a sensibus acceptae.” (Summa Theologica, I, 84, 6 ad. 2.) “There is an activity in the soul of man which by separating and joining, forms different images of things, even things not received from the senses.” Quoted in Umberto Eco, The Aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas, trans. Hugh Bredin (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1988), 172. There is a different operation at play here, which adds an imaginary component nowhere to be found in nature. With respect to Fra Angelico we could call this something almost analogous to a Kantian category, but a voluntary one (belief ). Through this the mystery of the image can be understood, the similarity being that both are prerequisites for seeing. Aquinas’s quote draws closer to the discussion of natural objects as a possibility, if not a necessity, for the construction of something that is not already given in nature.

7. Georges Didi-Huberman, The Power of the Figure: Exegesis and Visuality in Christian Art (Umeå: Department of History and Theory of Art, Umeå University, 2003). Henceforth cited as The Power of the Figure with page number. The following presentation is a summary of Didi-Huberman’s main points.

8. Golgotha is literally “the place of the skull,” which here also invokes the last hours in the life of Christ. In this respect we could also link life and death together, from the incarnation to the crucifixion, in a slot of time containing Christ’s whole life. This is also pointed out by Didi-Huberman in his Ouvrir Vénus, 57.

9. This could also be understood allegorically, as the choice of pure seeing.

10. Fra Angelico painted two Annunciations in the San Marco convent. One is located in the north corridor and the other in cell three. Unfortunately this is not the place to undertake a more detailed study of the two versions, and here I have focused on the general features of The Annunciation.

11. The theological discussion whether the human soul bears with itself a vestige of God’s touch in the Creation, is too far-reaching and complex to be summarized here, although it should be noted that this question was highly relevant to Fra Angelico.

12. Albertus Magnus, De bono (4.2.479), in H. Kühle et al (eds.) Opera omni, vol. 28 (Münster, 1951). Henceforth cited as De bono with page number. Here quoted from Fra Angelico 174f.