The Case [study] of the Missing 18-½ Minutes

Susan Schuppli

Press Play to Begin: At some point during the evening of June 20th 1972 a conversation between two men was secretly taped on a SONY TC-800B reel-to-reel voice recorder: an innocuous machine that uses 0.5mm tape, and was set to run at the irregular speed of 15/16 IPS—or half the rate of a standard tape recorder. In keeping with this low-fidelity recording mode, the tiny lavalier microphones that picked up this particular conversation were cheap and poorly distributed throughout the space. The result was a tape of degraded sound quality produced under deficient recording conditions.

Fast-Forward: It’s 1973 and an entire nation is now magnetized by the pull of forces unspooled by this single reel of 0.5mm tape. Tape 342, as it is officially referred to, is but one of a sprawling archive of approximately 3,700 hours of audio recordings taped surreptitiously by the late American Republican President Richard Nixon over a period of several years. Known as the Nixon White House Tapes, these recordings detail conversations between the President, his staff, and visitors to the White House and Camp David. Of the many thousands of audiotapes confiscated from the Oval Office, Tape 342 remains by far the most infamous. Not because of the damaging or volatile nature of the information it contains but precisely because of its absence: a gap in the tape of 18-1/2 minutes. A residual silence which is haunted by the spectre of a man who refused to speak, who refused to fill in the gap and suture the wound that opened up the corruption of the American political system for all to see.

This gap takes place during a conversation between Nixon and J.R. Haldeman (White House Chief of Staff) three days after the break-in at Democratic National Committee Headquarters in the Watergate Hotel. The timing of the conversation on June 20th and subsequent tape-gap so close to the temporal unfolding of the Watergate scandal have lead many to speculate that the tape must have contained highly incriminating evidence. Evidence which perhaps implicated Nixon himself in the crime. American constitutional law, under the aegis of the Fifth Amendment, gives one the right not to speak on the grounds that such speech may be self-incriminating. It does not however allow one to take back or erase something already spoken.

Existence of the White House taping system was made public during testimony before the Senate Watergate Committee in July 1973, but the equipment was not removed until after the disgraced President left office a year later. Although the muteness of both the tape and the man defied efforts to conjure forth ‘truth’ in 1973, the tape was still understood to be an important historical artifact that needed to be treated accordingly. Fear of disturbing the few remaining magnetic particles that clung to the 18-1/2 minute gap was immediately recognized and after a mere half-dozen playbacks the tape was permanently removed from circulation and placed into the storage vaults of the US National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in College Park, Maryland. There the tape has lain undisturbed in cryogenic sleep for over 30 years at precisely 65 degrees Fahrenheit and 40 percent relative humidity, waiting like a somnambulant bride for that moment when the kiss of technological progress will reawaken it. Moreover, the tape waits for an explicitly digital caress that will not only revivify but also restore its capacity to speak. Friedrich Nietzsche in describing the disconnect between certain inert forms of historiography and the vitality of everyday life writes,

‘Here is snow, here life has grown silent; the last crows whose cries are audible here are called where to fore, in vain, nada!’ (Nietzsche, 1969: 157)

Entombed within the hushed vaults of the archive, the rhetorical program of technology as deterministic and progressive, pledges to return the tape to the dynamism of the living. The archive leverages the crisis of the past, the partial erasure of Tape 342, against the projected technologies of the future. A wager that further developments in forensic technology will stave off the entropic incursions of time and revitalize the physical condition of the tape. In 2001 NARA initiated a process to test the 18-1/2 minute gap in an attempt to recover erased audio material. Several tests were conducted over a period of two years using highly specialized forensic technologies. To date all such tests have failed. In reading through the NARA press releases as they relate to Tape 342, it’s clear that the history of the tape is still waiting to be written and is therefore intimately conjoined with teleological accounts of technological development. As a national archive and steward of its nation’s heritage, NARA is mandated to implement the rational ordering and classification systems that Michel Foucault analyzed with such prescience in The Order of Things. Foucault also discussed the autopsy of the body in similar terms in The Birth of the Clinic.

‘Not merely the scalpel cuts open the medical body; rhetorical formulations, silent and otherwise, made it possible for the opened body to “speak”. If the body were to speak out of its silence, it had to be composed, patterned. It had to be ordered.’ (Doyle, 2002: 64)

In spite of its duty to police the objects entrusted to its care, one senses that Tape 342 has only ever been placed under temporary house arrest and that NARA itself is inflicted with a kind of archive fever, a malady that longs for originary truth: the fantasy that one day technology will be capable of restoring meaning to Tape 342. In his short text of the same name, Jacques Derrida describes suffering from archive fever:

It is to burn with a passion. It is never to rest… It is to have a compulsive, repetitive, and nostalgic desire for the archive, an irrexpressible desire to return to the origin, a homesickness, a nostalgia for the return to the most archaic place of absolute commencement. (Derrida, 1995: 91)

In an earlier passage, Derrida stresses that the question of the archive is not a question of the past. It is a question of the future, the question of the future itself, the question of a response, of a promise and of a responsibility for tomorrow. The archive: if we want to know what that will have meant, we will only know in times to come, later on or perhaps never. A spectral messianicity is at work in the concept of the archive and ties it, like religion, like history, like science itself, to a very singular experience of the promise. (Derrida, 1995: 36)

If the rhetorical pledge of NARA is to rescue Tape 342 from its imprisoned state of silence, Derrida reminds us that the question of the future must remain open, that the full significance of the tape will not be understood even at the moment that its gag order is lifted—the moment of its revelation. The task of this paper is to conceptually extract Tape 342 from its archival mooring, to remove it from the contagion of le mal d’archive in order to consider it as other than a mute artifact lying-in-wait for its eventual resuscitation. This strategic gesture acknowledges that Tape 342 already speaks in many complex ways. For in fact the tape is not silent, it is resonant with the sounds of clicks and magnetic detritus. The tape noise speaks a language but not one that is intelligible in terms of cognitive human speech patterns. Nixon’s act of ‘erasure’, rather than destroying the sonic transmissions of the tape, radically reinvents the tape, renewing its orality so that it now speaks a kind of machinic glossolalia.

However, the recognition of Tape 342’s enunciatory capacity is not simply a conceptual problem that requires a critical intervention, but as Isabelle Stengers makes explicit, demands that we consider

‘The possibility that it is not man but the material that “asks” the questions, that has a story to tell, which one has to learn to unravel.’ (Stengers, 1997: 126)

As an ontologically driven detective story, Stengers argues that it is not man’s grey matter that needs to be harnessed (à la Hercule Poirot) in order to solve the mystery of the missing 18-1/2 minutes, but that matter itself both contains the clues and poses the questions.

STOP: What stories does Tape 342 want to tell and how might we listen intently to our materials without determining in advance the means by which they will be made to speak? As Stengers warns us: no methodology can deny that the nature of its interrogation also actively produces that which is interrogated. How might we listen to Tape 342 without actually going to College Park, Maryland and entering the archive?

Changing definitions of silence were central to shaping both the public perception of Watergate and the ways in which the prosecution developed their arguments. Silence shifted from the aphasiatic body of Nixon to the absence of the subpoenaed tapes and upon their recovery to the 18-1/2 minute gap in Tape 342. Through this process of displacement silence was reconfigured as the very means by which material artifacts could begin to speak for themselves. In John Cage’s extensive writings on silence, particularly after his legendary visit to the anechoic chamber at Harvard University, he insists upon the impossibility of complete silence. As the story goes, Cage was perplexed to hear two sounds in the anechoic chamber, which by definition as a vacuum should have been soundless. When he queried this residual sound, he learned that he was in fact hearing the interior sounds of his own body,

‘the low throbbing of his blood circulating, and the high-pitched sound of his nervous system’. (Kahn, 1999: 158)

Cage thus conceptualized silence as always-sound, a state of sonic contingency that is no longer attached to specific enunciatory acts, such as his famous silent piano performance 4’33” but is a continuous unfolding that ‘resonates from each and every atom’. (ibid: 159). The act of erasure, like the concept of silence, is a technical misnomer that is immediately refused through an empirical investigation of the tape recorder itself, which alas reveals only six buttons: PLAY, STOP, PAUSE, REWIND, FAST-FORWARD and RECORD. The most important button is missing. But not only is it missing, the ERASE button has in fact never existed.

The technical organization of an analogue tape recorder does consist of something called an erase-head over which the tape passes each time the record button is activated. Erasing is only ever achieved as an abstraction, a by-product that the act of recording sets into motion only to turn around and negate. Immediately upon passing over the erase-head, the tape glides over the record-head, which reassembles its electro-magnetic particles and re-inscribes it with a kind of soundless sound.

The alternating positive and negative fields emitted by the erase-head reformat the tape so that minimal electronic bleed is archived by the substrate. An effective erase-head in reducing the signal by at least 60 dB achieves minimal noise-telegraphy. Only a bulk-eraser, where the reel of tape is immersed in and withdrawn from the field of a large AC magnet, operated at the frequency level of a high-voltage power line, can actually eliminate almost all extent tape noise. In short, it is virtually impossible to erase an analogue tape, only the digital allows for the deletion of a track, but even then deep-data recovery is still possible.

Although Tape 342 was recorded on a SONY TC-800B, it was determined by the Advisory Panel to Judge John Sirica (1974), that a UHER 5000 was the machine that actually erased or re-recorded the 18-1/2 minute portion of Tape 342. This machinic deterritorialization increases the likelihood of conserving latent vocalizations.

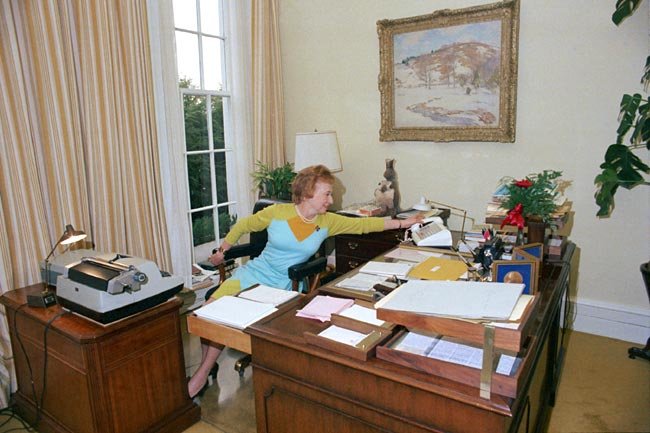

‘A crack in the erase head, a dust mote on the tape or heads, slack in the tape at start-up, a misaligned head’ would have severely compromised the erase-head’s effectiveness. (Mc-Nichol, 2002: 3) When news of the tape glitch was made public, Nixon’s secretary, Rosemary Woods claimed that she might have inadvertently caused the erasure while transcribing the tape by pushing the wrong foot-pedal on the UHER 5000. However when audio experts examined the tape in 1974 they concluded that the RECORD/STOP/RECORD button had actually been pressed 5 to 9 times, thus refuting the secretary’s attempted admission of guilt.

Reporters were called to the White House to watch her perform a reenactment, and the photos of her performing a tremendous stretch, were deemed to be implausible.

Qualified researchers who have had access to copies of Tape 342 describe the 18-1/2 minutes of silence as follows:

‘At the point of the first erasure, the muffled conversation is suddenly replaced by a buzzing noise, presumably the sound of a 60-cycle hum leaking from the power grid as interpreted by a high-grain microphone input circuit. Throughout the gap, the buzz occasionally drops in volume, but never is there any discernible speech.’ (McNichol, 2002: 2)

Archivist of the United States John W. Carlin announced (May 8, 2003) that he has accepted the recommendations in the final report of the National Archives Technical Evaluation Panel… Based on the results of two tests that were conducted by participants in an open-invitation proof-of-concept exercise, Mr. Carlin decided not to proceed with further testing…

“I am fully satisfied that we have explored all of the avenues to attempt to recover the sound on this tape. The candidates were highly qualified and used the latest technology in their pursuit. We will continue to preserve the tape in the hopes that later generations can try again to recover this vital piece of our history. (http://www.archives.gov)

The narrative motif of loss and salvage remains central to NARA’s commitment to Tape 342.

This archival desire constitutes the baseline for an argument that contends that the rhetorical framework of recovery that has been overlaid onto Tape 342 disavows its present status as already fully enunciatory. Moreover, this paper argues that NARA, in focusing upon the singular goal of the ‘recovery of intelligible speech’ thwarts the possibility of activating other potentially generative narratives. Emphasizing the promissory note of technology accentuates its messianic impulse to resurrect the artifact for us at some future date.

Asserting the tape’s conceptual purchase with the past, as well as with the future yet to come, disavows its immanent potential to say something right now. And yet despite NARA’s archival vigilance the passage of time will inevitably change the ways in which we perceive the object’s meaning, even in its protracted state of suspended animation. This temporal inflection has already marked the tape and is doing so right now within the very pages of this text.

Aden Evens in his article ‘Sound Ideas’ provides a detailed analysis of analogue and digital music recording techniques in order to account for perceived differences in the psychoacoustic dimensions of sound. Audiophiles often assert that analogue phonographic equipment creates a smoother, fuller, and richer sound in spite of the capacity of digital technology to produce much cleaner recordings. Evens makes two points that are important to the discussion of Tape 342. First, that it is not so much noise—the scratches and surface debris that interferes with grooved sound—which creates musical affect and expression, but rather the high frequency rates of analogue recording that the body perceives only physiologically at the level of cellular vibration. Digital sampling, by contrast, limits the recordable range to that of human intelligibility. In short, it cuts off those frequencies that register beyond the accepted threshold of human hearing. Evens’ second point concerns the method of digital sampling itself, which takes sound measurements at precise and regular intervals and then fills in the space between measurements through a process of interpolation thus creating the illusion of continuity and flow. In actuality, the digital track is infinitely divisible and can always be reduced to a series of singular states along a syntagmatic axis.

The high level of digital encoding that Tape 342 underwent throughout the years of NARA’s technical feasibility studies and subsequent admission of failed recovery is not entirely an open and shut case. The interval of the digital sample regardless of its hyperbolic frequency rate could theoretically contain information that the process of interpolation simply overwrites.

The space between the digital intervals could, in principle, contain the entirety of Nixon’s syncopated lost speech, that is, if interpolation were eliminated from the process. As Evens makes explicit any variations that occur in the time between two digital samples will be missed entirely. Only the digital with its comprehensive program of acoustic archaeology could retrieve sufficient data to open up the remote possibility of a series of speech-acts occurring within the intervals. Stengers dares us to call an innovative hypothesis: the remote possibility of a series of speech-acts occurring within the intervals - a propositional fiction rather than a hypothetical thesis that we set out to test and/or prove.

At this point in the text, let us press the PAUSE button for a moment and reflect upon Stengers ontological provocation to listen to the questions that the material itself wishes to ask. While the concept of the interval in digital sampling currently offers the greatest likelihood of recovering traces of human speech, the machinic utterances that unwind as the tape recorder itself reels off towards an unknown future have the ability to activate even more radical imaginary registers. In comparison with the network of speculative ideas and possibilities that the gap in the tape invites, the recovery of intelligible speech seems a rather pedantic objective.

Sound is the chatter of atoms that reverberates within all bodies and objects whether carbon or silicon. It is the expressive potential of a cluster of pure sine waves as they ripple across smooth surfaces, entering and exiting conduits to trigger responses deep within the subcutaneous layers of matter - a journey chronicled by the vibrations of an infinite frequency range. To a detective/researcher, Tape 342 offers a complex array of possible investigative leads. Only a few have been followed in this short text. There are many more sources to track down. We have already witnessed the dead-end that comes with jumping to conclusions and making assumptions. Only the team of archivists and scientists at NARA has the rhetorical authority to proclaim the ‘case closed’ but that should not deter further inquiry on our part.

Whether the volt-producing machine of the digital or the mechanistic apparatus of the analogue, a media object is never simply silent or inert; it is always already animated through its connective tissues to the machinic assemblage of the social. To quote Gilles Deleuze, ‘machines are social before being technical. Or rather there is a human technology which exists before a material technology.’ (Deleuze, 1988: 39) Although the ontological status of Tape 342 is anchored in its materiality as a technical artifact, it is also a contingent archive containing an 18-1/2 minute record of an incident or an accident. As an event it calls for a narrative account of the past and future yet to come, and as an object it immediately turns around and annuls its discursive status as merely a rhetorical overture delineating a set of temporal fictions.

‘The present and future diverge from the past: the past is not the causal element of which the present and the future are given effects but an index of the resources that the future has to develop itself differently.’ (Grosz, 2005: 38)

REWIND: Tape 342 is ultimately a placeholder for the multiplicity of different recording options that the machine has to mix new tracks and playback alternate histories.

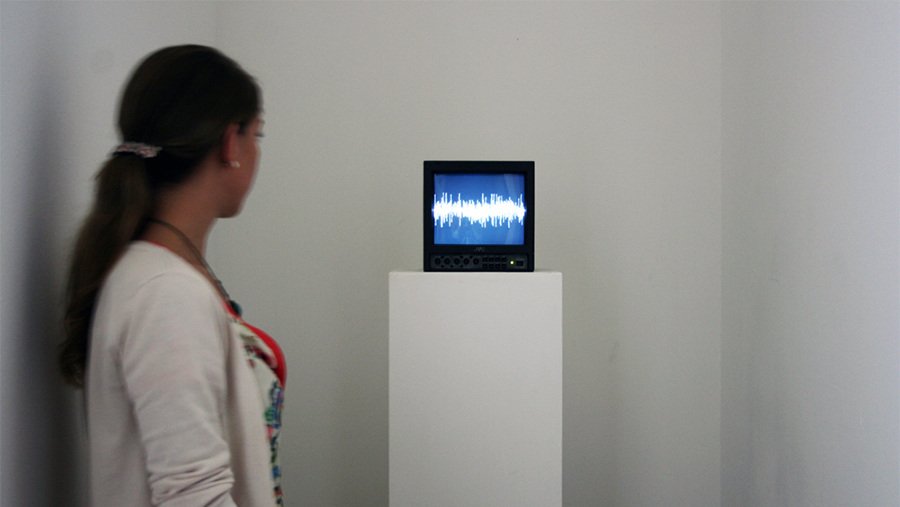

Susan Schuppli, Tape 342. The 18-½ minute audio copied from Watergate Tape 342 (courtesy of NARA) and converted into a video file to emphasise the highly energetic nature of the “silent” tape-gap. Presented on a 10″ JVC monitor with a digital media player. Listen to the an excerpt of the 18-1/2 minute erasure below.

Susan Schuppli is Reader and Director of the Centre for Research Architecture, Goldsmiths University of London, where she is also an affiliate artist-researcher and Board Chair of Forensic Architecture. Her work examines material evidence from war and conflict to environmental disasters and climate change. She has published widely within the context of media and politics and is the author of the book Material Witness published by MIT Press in 2020.

References

Carlin, J.W. ‘Archivist Accepts Watergate Tape Panel Recommendations’ (2003) The U.S. National Archives & Records Administration

[http://www.archives.gov/press/pressreleases/2003nr03-43.html] accessed on 28/11/05

Derrida, J. (1995) Archive Fever. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Deleuze, G. (1988) Foucault. London: The Althone Press.

Doyle, R. (2002) Wetwares: Experiments in Postvital Living. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Evens, A. (2002) ‘Sound Ideas,’ in B. Massumi (ed.) A Shock to Thought, pp. 171-187. London: Routledge.

Grosz, E. (2005) Time Travels. London: Duke University Press.

Kahn, D. (1999) ‘John Cage: Silence and Silencing,’ in Noise Water Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. Cambridge: MIT Press.

McNichol, T. ‘Richard Nixon’s Last Secret’ (2002) Wired 10.07 [http://wired.com/wired/archive/10.07/nixon_pr.html], pp. 1-5 accessed on 25/11/05

Nietzsche, F. (1969) The Genealogy of Morals, trans. W. Kaufman. New York: Vintage.

Stengers, I. (1997) Power and Invention: Situating Science. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.