Reinventing Unpredictability

An Interview with Yona Friedman

By Hans-Ulrich Obrist

Introduction by Meike Schalk

Yona Friedman was born in Budapest in 1923, and passed away in Paris, February 21, 2020. He studied at the Technical University in Budapest (Budapesti Műszaki és Gazdaságtudományi Egyetem) and in Haifa. His work has spanned areas ranging from architecture, art, and animated film to education and writing. He has participated in numerous art biennials including Shanghai, Venice and Documenta 11. His highly visionary ideas have nurtured various generations of architects and urbanists, influencing groups such as Archigram and Kenzo Tange.

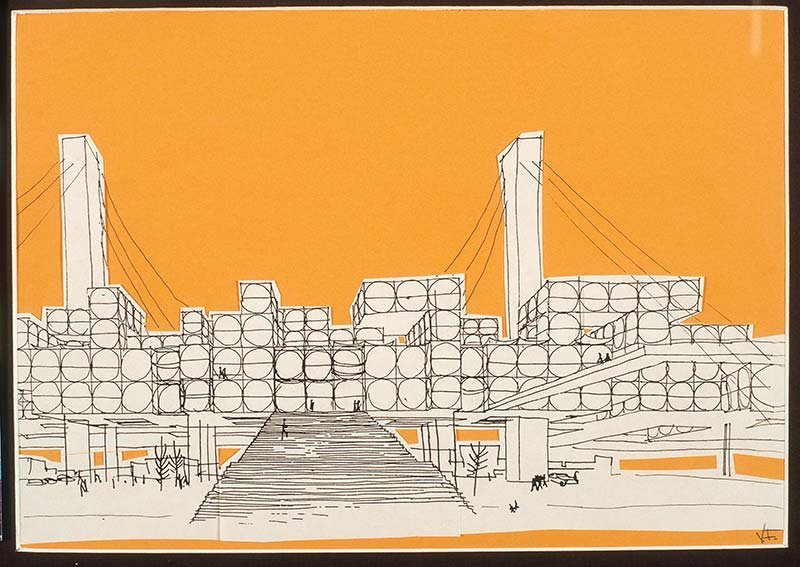

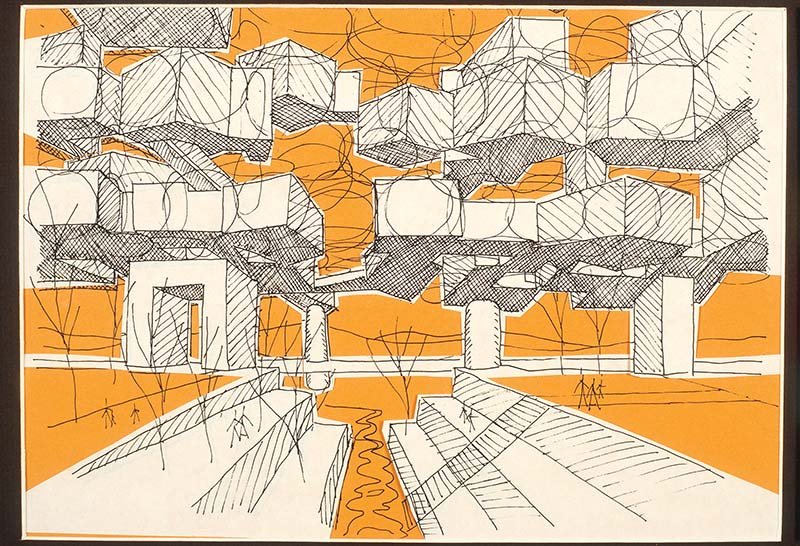

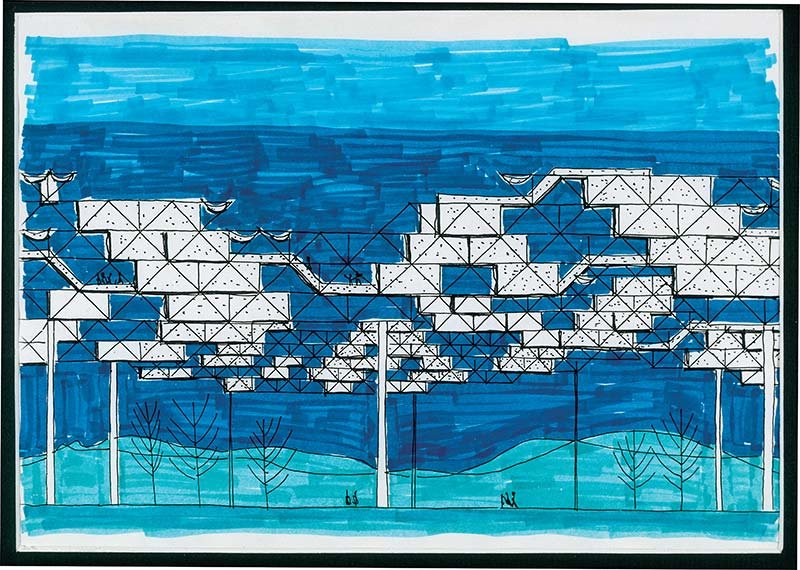

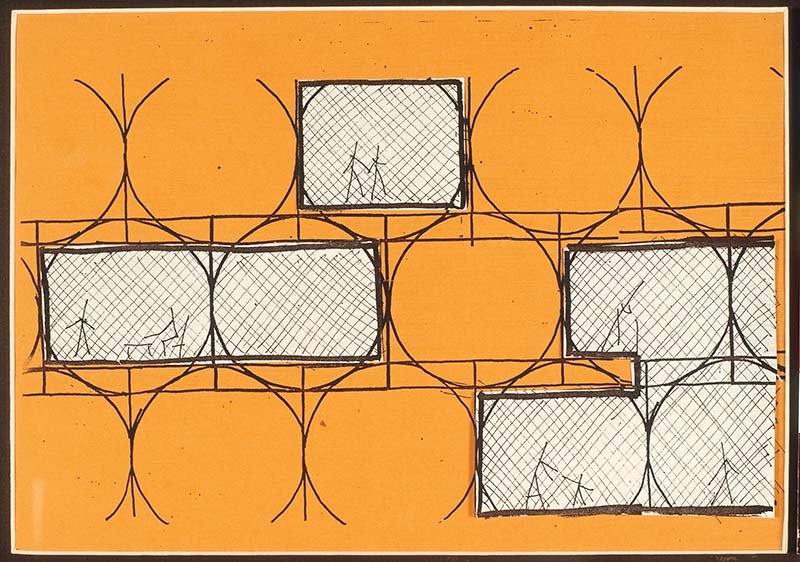

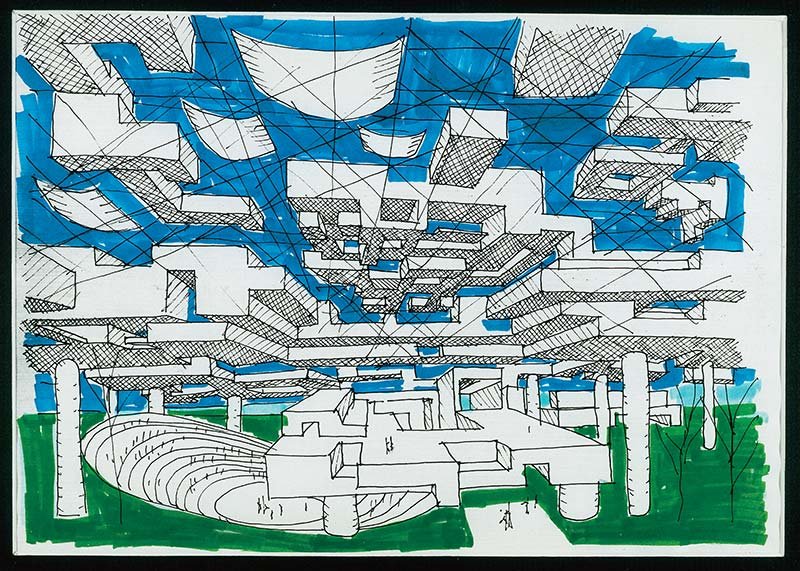

In 1957 Friedman proposed that all institutions founded on eternal norms become subject to periodic renewal – marriage, property rights, etc. He called this new form of a societal organization a theory of mobility. As the greatest obstacle to its implementation, he pointed towards the rigidity of the built environment. “Mobile architecture” described less a moving structure than an architecture of flexibility, a system that offered built-in adaptability to individual use. In his “Program of Mobile Urbanism,” written in 1957, Friedman envisioned a lightweight structure on pilotis that would touch a minimum of surface, was easily demountable so that it could be transported and ready to re-use. Those infinite systems formed clusters of carrying and containing structures. It is obvious that the differentiation between architecture and urbanism is abandoned. This new spatial city may hover above an old one, bridge rivers, oceans, and formerly inaccessible areas. Friedman worked in concert with several other professionals and in movements at the time, advocating similar ideas, among them the artist Constant Nieuwenhuis and his utopian urban project New Babylon, and the engineer Konrad Wachsman and his prefab techniques and space frames.

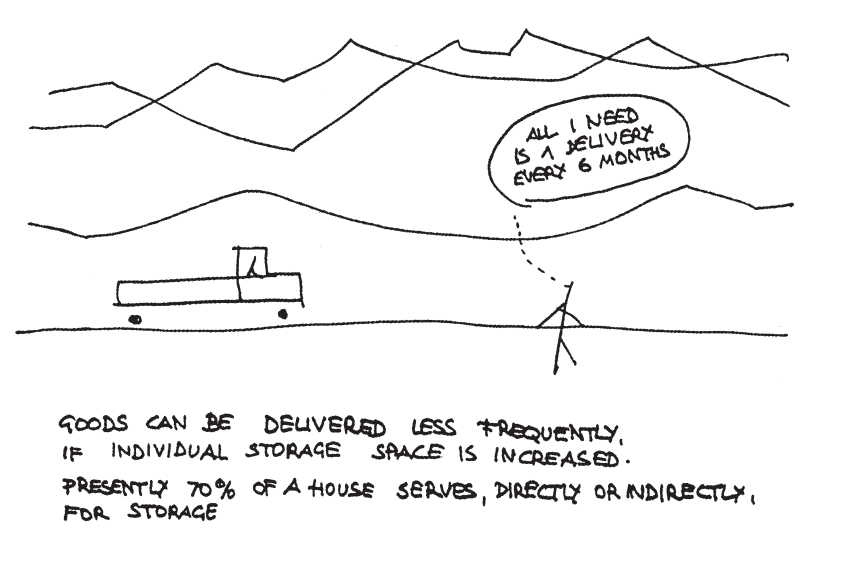

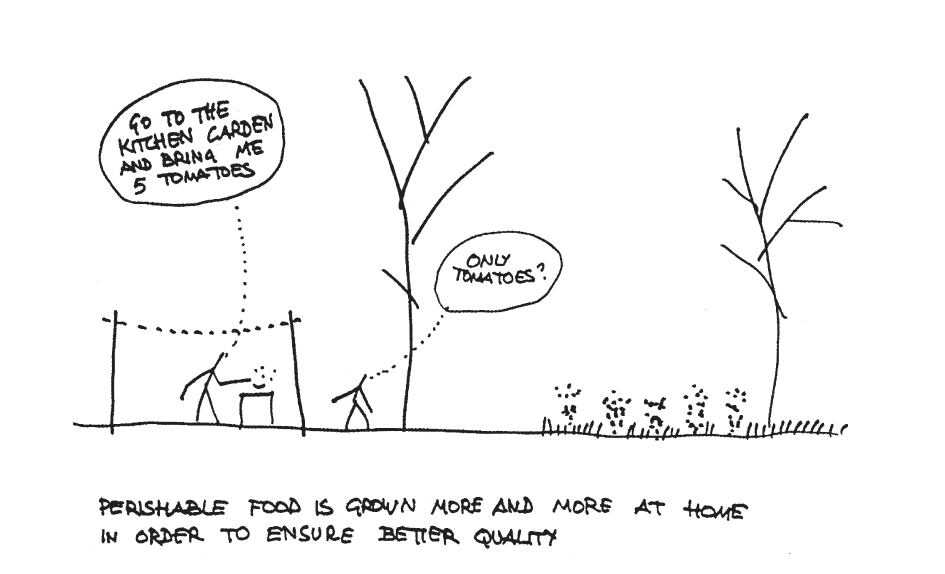

What was significantly new about Yona Friedman’s (infra)structures was the way they were presented – bringing together and communicating the possibility of public choice at the level of an open democracy – by organizing axiomatic spatial structures that could change from any type of inhabitation to another with a minimum of friction and loss of energy. As such, Friedman’s work goes far beyond architecture, engineering, and urbanism, it encompasses many other fields, such as sociology, art, animation film, etc. Beside his techno-utopian concepts, Friedman’s work for UNESCO on studies for Third World housing since 1976 was of significance, as well as his Museum of Simple Technology in Madras, India, completed in 1987. Throughout his work, there has been a fundamental interest in finding not only ways to communicate about urbanism and planning, but also to transmit knowledge about food, housing, health-care, etc., by employing media, such as cartoon and animated film in order to reach a larger unschooled audience. Examples are: Urban Mechanisms, 1963, Simple Encyclopaedia, 1968, and Popular Encyclopaedia for Survival, 1980.

Yona Friedman in his home in Paris. © Jean Leonard

Hans-Ulrich Obrist: My first question: you were speaking of the inexact, using the example of this sheet of paper. Would it be possible, in relation to science, which is normally considered “exact,” to speak of an “inexact science”?

Yona Friedman: Scientific theories are only supported by what we perceive, by that part of our perceptions that we interpret as the external world. First we make an image of the world, then we try to adapt it to reality (an imaginary one, it should be noted). At a conference in Minneapolis a couple of years ago, held by The World Academy of Arts and Sciences, I made a remark on mythologies – all sorts of mythologies: they all correspond to the experience of a human observer, just as with all types of scientific theories. All mythologies provide “predictions”: they explain and predict events. The difference between mythologies and scientific theories is that the attention (of the observer) is directed toward different domains. I consider the current theories at our disposal as a particular mythology. We direct our attention to certain things and not to others: “we invent a world” (of science), and then we try to adapt to this invention, to prove that it stands up. But our proofs, all our proofs, are solely based on “statistics” (and statistics doesn’t prove anything, it only analyzes the “frequency” of events, and not the events themselves). I try to see the world not simply as an entity uniquely describable with statistical methods, but as a world composed of individual entities that I (in my theory) call “granules of space,” entities whose behavior is entirely unpredictable. Of course we may describe their behavior statistically, but we can not predict them from one moment to the next. These “granules of space” (and their behavior) are unpredictable, erratic.

HUO: Is there a connection here to uncertainty? I did an interview last week with Ilya Prigogine in Brussels, and he used that term.

YF: I know Prigogine, I met him back in 1977. I also knew Heisenberg, whose seminar I followed in 1941.

HUO: Was Heisenberg your professor?

YF: In 1941, he was invited to a seminar in Budapest. I was still in high school, but the seminar was public. And I was of course very impressed.

HUO: In what way has science influenced your way of working? You went on to study architecture, but did you also pursue interdisciplinary studies?

YF: My work (which stems from my attitude towards science, i.e., the acceptance of the fundamental importance of individual acts) starts from an unpredictable individuality, related to the domain of sociology. The actions of individuals are completely unpredictable, even for the individuals themselves. But often these unpredictable actions are decisive (they determine complex processes). And in architecture, planning is nothing but a statistical fiction (a fiction that does not exist in “reality”). The important decision is the one made by the individual, and it is wholly unpredictable. No “individual,” be it in particle physics or in sociology, behaves in conformity with abstract laws. This is what I in my latest book call “the principle of individuality,” and it postulates that an individual cannot be substituted for another, and that two actions, considered as identical, are not in fact identical at all. From this follows something I find amusing: I accept that the world takes on form – as all great physicists (tacitly) postulate – in accordance with a unique and fundamental law; but this law does not explain that which results. There is an example of this that I like a lot, and which refers to arithmetic: the totality of natural numbers is formed by the simplest imaginable construction (one, plus one, plus one, etc). But if I write down a number containing a million digits, there is no mathematician who at first sight could enumerate all the properties of that number (even if he knew the properties of the adjacent numbers).

HUO: And complexity would be a consequence of this?

YF: This observation goes beyond the concept of “complexity.” I prefer to talk about “complication.” The maximum complexity of a totality is limited by the number of possible relations between the elements in the totality. A “maximum complication” on the other hand could be infinite, even in a finite totality. The “complication” can be produced by applying an indeterminate number of wholly arbitrary rules. In order to visualize this, take the case of a line. Its complexity is negligible, but I can twist it as much as I want, augment its “complication” without increasing its “complexity.” An arbitrary rule – and the case where there is no rule at all, which is a special case – corresponds to “invention.” Science and invention are closely linked; all theory is invention, “artistic” invention. Science and art are two aspects of the same thing.

HUO: So you don’t see any big divides among the practices of an artist, an architect, and a scientist?

YF: Every artist is a little bit of a scientist, and every scientist is a little bit of an artist. This separation between art and science is very recent in history.

HUO: A couple of weeks ago I had a discussion with Iannis Xenakis, and similar questions were brought up. Should we once more reunite these disciplines – and this without falling into interdisciplinarity, which would be another discipline, and thus less interesting. I would like to ask you how you situate your own practice: looking around in your apartment, one could say that there are traces of the work of a city planner, of an architect, and of an artist, given what we see on the walls. This is really a practice located “in between.”

YF: Perhaps I’m not very “disciplined,” but I don’t think a discipline could exist other than as an (unjustified) monopoly. I am quite simply a normal human being who projects, for himself, an “image of the world” without setting up any barriers among the elements of this vision. But I have the courage to “externalize,” to express my image of the world. I dare speak about science without being trained in it, I dare speak about architecture as a sociologist, and of sociology as a form of communication. I have tried to construct theories based on the same line of reasoning in science and in sociology: the principle of individuality,” mobile architecture, “urban mechanisms,” the “critical groups,” can all be seen as expressions of the same line of thought.

HUO: When you talk about urban mechanisms, what type of law are you referring to?

YF: The law of the “critical group” (the determination of the reach of the “grapevine,” as it were), a law that I discovered in 1973, is now accepted by sociologists (more accepted than my observations on architecture, since they disturb the monopoly of a profession). By “critical group” I mean the limit in size of a group within which communication can be propagated without being completely deformed. The current experience of the Internet I think really validates my theory.

HUO: Do you spend a lot of time on the Internet?

YF: I don’t use it, but I observe those who do. I am fully aware (following my theory) that communication is not uniquely dependent on the tools that are used. If two people cannot understand each other face to face, then they will not understand each other over the phone.

HUO: This is interesting, for when it comes to issues of society and the environment, your work has exerted a tremendous influence on artists, architects, and city planners. And indeed on sociology as well.

YF: When it comes to science, I try to bring with me the same “background”: our society and our sciences make use of the same mental models. And Prigogine, too, made a connection between science and sociology.

HUO: He really created a bridge between science and society, and he is developing these questions even further now.

YF: This is inevitable. I find it embarrassing that architects know nothing apart from architecture, since this is not enough. The same goes for artists, scientists… One of the scientists I like is Denis Gabre, who really gets involved in everything. I got to know him in Italy.

HUO: Speaking of interdisciplinarity, there is a text by Julia Kristeva on the anxiety of interdisciplinarity. On the one hand, there is the idea that interdisciplinary activities like yours are highly influential, much more than those that remain confined to the ghetto of a unique discipline; but on the other hand, there is in society a great resistance toward this, a profound anxiety. I would like to hear your comments on this anxiety, and how we could move beyond it. I’ve often noted the presence of this anxiety, for instance in universities or in museums, and it is an real obstacle.

YF: I will answer by way of a detour. Some twenty years ago, I wrote an article called “The Right to Understand.” The right to understand – this means that all human experience can be expressed in a language understood by all. I then showed that the different disciplines are trying to muddle that language. This they do for various reasons, in some cases to maintain monopoly, to maintain a class system. One might say that we live in a class system of formed concepts. We have an implicit image of the world that is… I don’t want to say “interdisciplinary”; I prefer “global” – since talking about interdisciplinarity is tantamount to accepting disciplinarity – global in the sense of a member of an African tribe, or this Indian tribe in the Brazilian rain forest, whose name slips my mind right now. They are architects, scientists, hunters, cooks, all at once.

HUO: They are generalists.

YF: Yes, and I would like to be a cook too, since I like it, and I decorate my apartment since it pleases me; I don’t sing because my voice does not please me, but I would not be the least ashamed to do it.

HUO: You don’t use the term interdisciplinary, or pluridisciplinary, or transdisciplinary, since they all imply disciplines. But what about the term global?

YF: I accept the globe, I cannot go beyond it for the moment.

HUO: Your activity is in the world, and in a certain sense the world is your activity.

YF: It is a closed system, but the largest possible one. And I must add that I learn a lot from my dog, and I say this seriously. In his behavior, I can sense that he has a global view, with-out any disciplinarity. He knows how to be-have when faced with isolated, and thus irrational, phenomena. There is no way to express this rationality, which I call “surrationality,” just as there is realism and surrealism, there is “rationality” and “surrationality.” This is a global rationalism, completely closed, that cannot be communicated to me.

HUO: Throughout our conversation I have been thinking about the dog, since you’re in a certain manner communicating with the dog too, which reminds me of Bruno Zevi who once did a famous interview where he referred all the questions to his dog.

YF: We’re talking about human intelligence. My dog understands me, but I don’t understand him. So who’s the smartest of us?

HUO: There is this book by the British scientist Rupert Sheldrake, Seven Experiments That Could Change the World, where he talks about experiments with dogs. The dogs knows at least ten minutes in advance when his master is going to leave.

YF: I wrote a paper on precisely that topic. If I want to do something, my dog knows this before I do. I attempted to extrapolate, and I claimed that he lives in another temporal system that I do.

HUO: Sheldrake in fact has a whole archive with letters sent to him by dog owners, and they all explain how the dogs really understand them. The Austrian television even made a film based on this: the dog is at home, and its owner comes out from his office 20 km from home, and immediately the dog sits down in front of the door. It’s pure telepathy.

YF:Yes, I think it’s a another space-time which is slightly different from ours.

Yona Friedman with his dog Balkis in his home 1998. Photo: Marianne Homiridis.

HUO: This leads to the question of the city, of city-planning. The fundamental question that I always pose myself, and that I would like to pose to you, bears on the fact that most often cities are organized in a way that ignores this other form of dialogue, of communication. How do you see the city today, or how can we within them see what you call “complication”?

YF: Ten days ago, at Columbia, I gave a talk on these questions. We may imagine the “hard-ware” of a city, but the “software” we don’t know. We speak of urban mechanism, which might explain some things, but a city is not used in the same way. It’s enough that people will gather in a different way, that they walk in different directions and in different ways, for the city to change. If people for some reason decide not to take a certain street, then the city is a different one. For me, the city at night and in the day, in the summer and in the winter, on Sundays and on weekdays, are all different cities. They have the same “hardware,” but the city is completely unpredictable. In this way, we once more come to the idea that all predictions about the city are merely statistical and false.

Yona Friedman, 1974. Photograph by Paul Almásy. Courtesy of Marianne Friedman-Polonsky

HUO: If one looks at your plans for cities from the 1950s and 1960s, there is an anticipation of how the Internet works. There is the idea that one can visit a city, a website, and it is planned and structured in such a way that it is never the same, and each visitor will activate different fragments. Duchamp said that it is the spectator that makes the work of art; would it be possible to say that it is the user that makes the city?

YF: An old phenomenon that we have become aware of is what I call mass individualism: each individual behaves differently, and yet there are masses. But they are just as unpredictable as a group of individuals. City politicians think they can predict how people will act. But, for instance, when people step into a cinema theatre, or a conference space, there is no telling how they will get seated. How they occupy space and time cannot beforeseen. This is why we are in a society whose interest lies in its continual displacement of the center. I’ve formulated a hypothesis on what I call “the society of weak communication.” The world is connected through avast network, but everyone is at the center of another group, like one’s neighbors. In the context of cities, I call this the private city. The persons with whom I communicate on the net are my private city. And no two such private cities coincide. This means that we all are mini-centers in an immense network, and mini-individuals within a vast system of behavior that can be described statistically, but which for me is not at all statistical. I think this disturbs the idea of the 19th century, this very 19th century that comes to an end this year. In fact, I think we are still completely in the 19th century, and not at all in the 20th. The last century only consisted of provocations. Inventions are perhaps beginning to occur in competitions. But even those who try to invent still do not know how to formulate it. Inventions will take place when this is no longer just tacit.

HUO: So you’re saying that the end of the 20thcentury is really the end of the 19th.

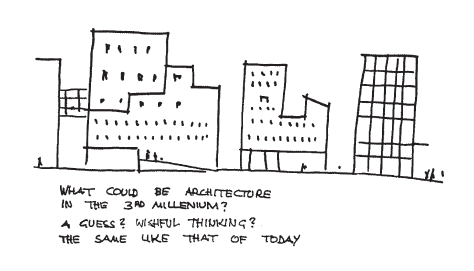

YF: Yes, if you look at architecture, for example, you see that the 20th century has invented nothing. We’re parasites on the 19th. There are very few ruptures in the history of architecture, perhaps four. The Romans broke with their predecessors; and the Gothic was surely a rupture. And then we had the 19th century, which we’re still living in. No doubt we have better knowledge of materials, and are able to calculate better, but our concepts all derive from the 19th century.

HUO: But if this is the case, then the question arises concerning your own non-realized urban projects: do your ideas belong to the 20thcentury, but are aimed at the 21st, since the20th is an as yet unrealized project?

YF: No, I still belong to this shift between the 19th and the 20th, but I commence the discontent. This is not enough for me. The nextstep is slowly beginning, and it will take hundred or two hundred years before it is formulated.

HUO: You have been talking a lot about urban models the last decades. Do you see the direction in which we are going, or is that unpredictable too?

YF: I think it is unpredictable. If there are no laws, something has to replace them. Throughout this century, one believed in order. We are starting to discover disorder. But disorder and order are the same thing, seen from different perspectives. There is only one person in whom I have found this idea, and strangely enough, this is Goethe – Goethe who was a specialist in talking about things he know nothing about and still getting it right. Goethe, for me this is always sublime banality. I admire him because has the same instinct as my dog, and I mean that as a compliment.

HUO:This idea of order and disorder has beendeveloped by Aligiero and Boetti, who did this beautiful book, The Thousand Longest Rivers in the World. Obviously, there is no way to measure rivers, and they took all the different sources that were trying to establish their length and ordered them according to reliability. And in fact, on every page you can also see all the other sources, and at the end, absolute order is absurd, and one can see that order is within disorder, and that every ordering system implies its own disorder.

YF: Yes, and this corresponds to complication. For instance the alphabetic order, which is complicated but not complex in lexicography. It is an invented order that structurally could be replaced by another order. But let me give another example: since the beginning of the 20th century, writers – i.e., narrators – have been wrestling with linear narration. Proust’s whole effort was to escape linear narration, but it can’t be done, since narration is necessarily linear, it’s a structure you can’t change. But you can always make a complicated narrative structure, as you wish. At the same time that I try to invent a new theory, I try to see if it can get hold of a reality.

HUO: How does this non-linearity enter into your urban projects, and especially into the idea of the ephemeral? You have talked about mobile cities or mobile urban structures. This is reminiscent of Constant and his New Babylon, but also of Cedric Price, Alison and Peter Smithson, and Peter Cook.

YF: I knew Peter Cook when he was still a student. Many of these people used certain things. I will try to explain on the basis of the idea of complication. If you observe the behavior of someone in the city, you can only observe his itineraries. An itinerary is by necessity linear. We could not image a non-linear itinerary. These itineraries can be very complicated if one looks closely and tries to grasp the mall. But nobody knows all the motives behind the complication. Sometimes I watch old news and suddenly there is this guy who crosses the street and just doesn’t fit in with the rest. I see what he’s doing, but I don’t know why. There is no theory that could provide an answer. And even the fellow in question doesn’t himself know why. This means that there are individual events that cannot be explained theoretically, contrary to what was believed in the 19th century, but also in the20th. For me, there is no conceivable element that could know everything. This means that there can be no rule for how a city should be, no rule for how its inhabitants should use it. There are some quite general rules, but they could change minute by minute.

HUO: This is really a statement against the“Master Plan.”

YF: Yes. This leads to the idea that I should make the hardware as soft as possible. This was my theory of mobile architecture. The hardware must be adaptable. In the 1960s, I made a sketch where I claimed that architecture would no longer be necessary in the 21st century. Imagine you’re living in a region where the climate is completely pleasant. Thus there is no need for shelter. There is no need for roads. I circulate in a helicopter or a delta plane. Suddenly all the hardware of the city is no longer necessary. It’s evident that we’re living in bygone days. The new is not the spectacular. And suddenly one realizes that the new has been around for a long time. This also explains why there are no disciplines; it is impossible to talk of one thing without refer-ring to another. This, however, is not interdisciplinarity, but rather the image of a global world.

HUO: You have developed a museum in India, and in your texts you remark that we can learn about urbanism from India, from how Indian cities function. Could you say something about your relation to India and its cities?

YF: What is interesting in the shanty towns or villages in the Third World, is the system of land ownership. In the cities of India, they have the same system we do. In a village, the system becomes more elastic. In the Turkish empire, you planted a tree and the ground up-on which the shadow fell became your property. This means that land can be appropriated. The same thing exists in the shantytowns of Istanbul: people plant trees. You can determine when a town was established by watch-ing the tree tops. Here the rules of property are different from the ones we’re used to. Unlike our system, it’s not planned in advance, it is not abstract like it is among us: we have a piece of paper with a drawing. It’s the piece of paper that explains everything. In the Third World, property is much more tangible and material.

HUO: You have been talking about the term “illegal city.” What comes to mind is the Kowloon/Walled City in Hong Kong.

YF: Hong Kong is highly planned. The illegality is expressed in the skyscrapers, in their savage facades, and when it comes to the city, in the Chinese junkers on the ocean. Rules of passage are respected and the rules of property are different, but not abstract. Fundamentally, I’m trying to give abstraction its proper place: the importance of the individual over statistics, of reality over that abstraction which is statistics. Abstraction is necessary, but it shouldn’t be overdoses. Let go of abstraction – we have a need for equilibrium.

HUO: When it comes to non-realized projects, there is a question that I always put to the architects and cityplanners that I’ve met, and that I like to put to you too: of all your “realizable” projects, which is the one you would most of all want to realize in the future?

YF: I have realized very few projects, I have only sought to demonstrate that “it’s possible.” What I would most of all like to realize, that’s quite simply a house of my own, my own small world (unfortunately, I don’t have the means to do it). It would have a maximum of fluidity, utilize different techniques for playing around.

HUO: This house would be a complex and dynamic, self-organized system. And the idea is that it should never stop.

YF: Individualism is something unknown to the individual him- or herself. I couldn’t care less about the Greek principle “Know Thyself.” One doesn’t know oneself!

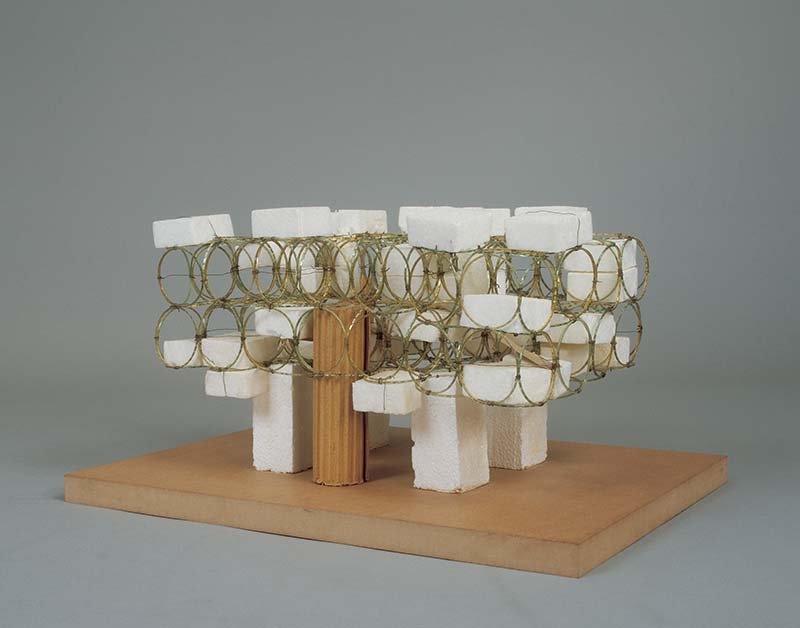

HUO: Could you explain these structures where circles are transformed into other forms?

YF: This circle is both one side of a tetrahedron and of a cube, I move from one system to another. The structures grow really fast.

HUO: The density of your apartment recalls Schwitters’ Merzbau.

YF: And above all, Schwitters had no written theory for the Merzbau. My decor is without theory too. Yes, there are wrappings on the wall, and all types of materials can go into it. And there are films, animated cartoons…

HUO: In the context of your work, the wrapping paper, that you use as readymade, turns into urban structures.

YF: Yes, it’s urban waste.

HUO: Could you say something about your museum projects?

YF: The Museum of Simple Technology I called a museum, but it was more like a “communication vehicle,” a kind of soft museum... I used a system of communication just consisting of cartoons. I made cartoons on quite concrete topics (food, health), for people without education. And in India, above all, I had an audience (approximately ten million). These cartoons, or manuals, as I called them, were distributed by the press and various organizations. And in the Museum of Simple Technology, the idea is that what was explained in the cartoons should now be demonstrated by the “things” on display. The museum presents the manuals as wall newspapers. It was a didactic museum, and not a museum for conservation. The construction was made for the demonstration of very simple and cheap technologies.

Yona Friedman, Museum of Simple Technology, Dhaka 2018.

HUO: These are “Do It Yourself” manuals.

YF: Yes, completely.

HUO: How many did you make?

YF: About a hundred. Even the Islamic Republic of Iran used them. UN wanted to set up this institution, but then there were changes, and they had a budget problem. I had to stop.

HUO: You have worked at the UN University?

YF: Yes, I taught there. The UN University was the patron for the institute I directed, but eventually they cut the budget. But I showed that it was possible to do.

HUO: This “Do It Yourself” idea is very interesting, a museum which doesn’t necessarily give you something to see, but works as a startingpoint, a self-service. When you did your project for the Centre Georges Pompi-dou, which is an interdisciplinary museum, how did you approach the architecture?

YF: To me, a museum is above all defined by its audience. With my manuals I tried to show the global nature of problems for a non-professional audience, by emphasizing all the things that are necessary for the survival of the poorest (health, water, social organization): how to set up a business with one person, how to relate to children, i.e., that which is important for the public. The Centre Pompidou is a mixture of conservation, the Museum of Modern Art, the library, etc. What I proposed for them (which I also proposed to MOMA) was a skeleton structure, a physical and, why not, also spiritual frame.

HUO: This would be an alternative to the idea of a project.

YF: The disposition of the volumes inside the skeleton was variable; with each generation a museum changes, it doesn’t find its form in a few years, it takes at least fifty years.

HUO: Would it be possible to talk about buildings in mutation?

YF: Maybe, but I prefer “buildings in constant change,” just as the city is constantly changing. There are no rules in nature, and the museum is also an image of the world.

HUO: In this logic of the museum, the school is like the city, and the city comes into the museum and the museum enters into the city.

YF: Absolutely. In a predetermined differentiation, in a provisional differentiation…