Re-Visioning Mies

Sven-Olov Wallenstein

What would be the legacy of the work of Mies van de Rohe? Is the true interest to be found in his avant-garde projects from the 1920s, or in the later work from the US, which might be viewed, symptomatically, as the final acceptance of the commodification of the avant-garde in postwar corporate US? Or does the glass box in fact indicate a moment—to be sure tenuous and short—of resistance, the posterity of which however harbors a multiplicity of possible continuations? In what sense, if any, could we, in the present, pick up where his work left off and shoot the arrow into the future?

This essay looks back on an earlier book of mine, The Silences of Mies,1 where the plural form was essential. My proposal engaged a range of topics more or less pertinent to Mies, but also outside of him as well as of architecture in the limited sense: the status of language in classical architectural theory from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the role of glass and transparency in modernism, but also the use of silence in the plays of Samuel Beckett and in the music of John Cage, as well as the theory of aesthetic autonomy and negation in Adorno and the libidinal aesthetic in the early work of Jean-François Lyotard. The underlying question was, however, whether the idea of negation and withdrawal that for many seemed to be the sense of the silence that has been ascribed to Mies would be able to account for the complex imbrication of art and technology that has characterized modernism throughout its history, for which the architecture of Mies served as one possible example, but indeed an exemplary example.

At the horizon, there was another and more general question, that of the avant-garde as a transformative event, in which art does not simply negate its past forms in a quest for the new that would render its inheritance obsolete, but itself undergoes a metamorphosis by entering into contact with emerging technologies and social changes, and redraws the boundaries of subjects and objects, space and time, which was the explicit claim in early theorists such as Sigfried Giedion.2 This does not imply that the ideas of negation, withdrawal, and resistance, as they has been handed down to us by a long tradition of critical theory, should be simply discarded, as some have claimed, but rather, that they need to be reworked in order to be able to account for the complexities of the present. In this sense, the plural form silences should be taken to indicate a transformational event inside architectural discourse, so that what from one perspective appears as emptying out, from another emerges as the possibility of other ways of speaking.

The present text also briefly presents as few reflections occasioned by the recent re-opening of the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, as well as by a series of artistic projects intervening in multiple ways in the legacy of Mies, on display in galleries all over Berlin, most of then around the time of the opening of the Neue Nationalgalerie. Given the wide variety of approaches and the sheer number of participants (around 70 artists in 30 galleries), any exhaustive discussion would be impossible, and what follows is only a series of snapshots and brief comments on various ways of bringing the past into the present.

Tectonics and nature

From its very inception, the work of Mies dealt with the implications of technology for art in a historical situation that the architect himself seems to have understood in terms of the progress of spirit toward a higher unity that revives a classical tradition by bringing it into the present.3 Already in the early work with Peter Behrens, whose architecture for the AEG in Berlin stands as one of the essential landmarks of the dialectic between technological construction and classical form on the eve of modern architecture, Mies came to perceive his task as the creation of “die große Form,” a grand form that raises technological structure to the level of a new monumentality. Fritz Neumeyer’s reading of this idea situates it as a sequel to a long debate stretching back to German Idealism, and proposes that we finally should understand it as the quest for a certain harmony, or a “bound duality,” that would allow the technical in its disruptive force to co-exist with a new freedom: “Mies enacted the destruction of architecture, using the liberating forces of modern construction to free the wall from its obligation of carrying load and proudly presenting the skeleton as the constituent element of the new architectural project.”4 In Neumeyer’s reading, the Barcelona Pavilion of 1929 is the first decisive work that sets itself the task of creating the conditions for these new spiritual values, and does this by making room for, or more precisely constructing the space for, subjective experience: the building is a “viewing machine,” whose significance can only be discerned in an active strolling around that brings subject and object together, and where the frame no longer signals merely a technological objectivity, but itself becomes an “instrument for perception.”5

First image: Peter Behrens, AEG Turbine Factory, 1909, Berlin.

Second image: Mies van der Rohe, Barcelona Pavillion [destroyed], Barcelona, 1929. Reconstructed 1983-1986.

In this perspective technology neither erases nor supersedes nature, but is supposed to fuse mind and nature. The spatial constructions of Mies provide a “concentration that allows the subject to step aside from the world while remaining within it, not retreating from it”6—a subtle and complex figure of resistance and affirmation, withdrawal and immersion, whose tectonic expression Neumeyer locates in the frame, as “the instrument of perception that creates isolation and connection at the same time.”7 In Neumeyer’s reading these steel skeletons, while having an obvious technological and material dimension, also make possible subjective experience in that they function as “viewing frames” that provide a different perspective on the cityscape; they are at once places for “stepping aside” and gaining a certain distance, as well as optical machines that provide a kind of visual immersion, especially as they appear at night in the luminosity of the Metropolis, when the building is both a translucent structure and itself a source of light.

In this sense, Mies’s last buildings can be understood as a termination point of a cycle of frame and light, the prime case being the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin, which allows the spectator to look at the artworks while still being connected to the city from a certain distance— the distance of a redeemed subjectivity, as it were, for which distance no longer signals alienation, but rather a reflexive autonomy, and in which, in Neumeyer’s formulation, the “opposite worlds of transparence and gravity, of technology and architecture finally were united.”8 And in an interview with Christian Norberg-Schulz from 1950, Mies appears to subscribe to precisely such a reading, and he speaks of a the need to attain “a respectful attitude toward things,” and says that we “should attempt to bring nature, houses, and human beings together into a higher unity. If you view nature through the glass walls of the Farnsworth House, it gains a more profound significance than if viewed from outside. This way more is said about nature—it becomes part of a larger whole.”9

Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, Plano, Illinois, 1951

Negative Thought

In the light of above interpretations—Mies as the proponent of pure building tectonics that, to the extent that it partakes in discourse, can only be an “artless” word, the honesty of Bauen as opposed to the rhetoric of Architektur, as well as of a fusion of mind and world, technology and nature—it might seem surprising that the architecture of Mies has become equally paradigmatic for a certain tradition of critical theory that emphasizes difference, division, and an irrevocable fracturing of experience. This tradition draws on the legacy of the Frankfurt School as well as Heidegger, sometimes combining them in such a way that the analysis of technology is paired with reflections on the fate of art and aesthetic autonomy in the commodified world of late capitalism. Here too, a recurrent theme, although inflected differently than in the claims for reconciliation, is that Mies’s work can be understood as somehow silent, and that it acts in terms of a withdrawal. By situating itself at the limit of the modern tradition, at the point of exhaustion of the formal vocabularies of architecture, or even of artistic expression as such, it is assumed to withdraw from the world into the sublime negativity expressed in the architect’s own canonic formula, “beinahe nichts,” “almost nothing,”—a nothing or a silence that may be read in many different ways, as we will see.

The analysis of Mies’s work that established the paradigm of silence, negation, and withdrawal is carried out in Manfredo Tafuri and Francesco Dal Co’s two-volume work Modern Architecture,10 where it occupies a crucial position in the chapter “The Activity of the Masters After World War II.” Tafuri and Dal Co here propose a reading of the fate of the European avant-garde, as it was gradually absorbed into the postwar corporate US culture and mutated into an international, placeless, and technological style. We are presented with several different endings of the heroic phase of Modernism, but the case of Mies seems to be most fateful and tragic in the sense that tragedy here becomes a conscious act, a supreme artistic achievement, and not just a waning of creative power.

Mies van der Rohe, Crown Hall, 1950-1956, IIT, Chicago.

Tracing the development of Mies in his American period, from the design of the campus at Illinois Institute of Technology, The Farnsworth House, and other projects, Tafuri and Dal Co claim to discern a gradual reduction to facts that entails a division from the surrounding context. There is, they say, a “renunciation that makes it possible to dominate the destiny imposed by the Zeitgeist by interjecting it as a ‘duty,’” and it is carried out in buildings that “assume in themselves the ineluctability of absence that the contemporary world imposes on the language of form.”11 The pièce de résistance of this analysis is the section on the Seagram Building (1954–58), where all of the themes that structure the interpretation of architecture as an essential intersection between technology, modernity, and capitalism come together in a few dense pages. Through a formal reading of the building and the way in which it sets itself apart from the surrounding city, Tafuri and Dal Co point to the what they call the “absoluteness of the object” and its “maximum absence of images” as a “language of absence” or a “void,” which is then projected onto the city (or more precisely, the division that sets the edifice apart from the city) so as to form “two voids answering each other and speaking the language of the nil, of the silence which—by a paradox worthy of Kafka—assaults the noise of the metropolis” in a “renunciation” that here becomes “definitive.”12 The building interiorizes the abstraction of social life in late capitalism as its formal autonomy (or “absoluteness”), but in this it also casts a negative light on the metropolitan landscape. The bound duality of Niemeyer, the stepping back that lets the subject appear in a higher unity, has here given way to a chasm that allows for no reconciliation.

Mies van der Rohe, the Seagram building, New York, completed 1958.

This self-consciously tragic move—a language that silences itself and withdraws from the world —then acquires its “parodic” counterpart (parodic according to the famous claim by Marx about history repeating itself, first as tragedy and then as farce) in the proliferation of corporate high-rises that would follow in the wake of the Seagram Building, where tragic silence is filled with empty verbosity and repetition.

The above interpretation welds together a series of motifs, from Marx, Kafka, Karl Kraus, Adorno, Heidegger, and probably a host of other thinkers as well. There can be no question here of attempting to do justice to Tafuri and Dal Co’s multi-faceted account of the trajectory of modern architecture,13 which still stands as the major landmark in the historiography of modernism, or to the intellectual environment out of which their work grew. Instead I will just pick up a few motifs, drawing on the later comments to these passages made by Massimo Cacciari, who highlights them as the core of the book.

It is Cacciari who supplies the connection to Heidegger’s analysis of technology, which at first may seem somewhat tenuous; Heidegger is mentioned in other parts of the book, but not here. Cacciari discusses this in his review essay “Eupalinos, or Architecture,”14 and he takes the reference to Heidegger as decisive for the project of writing a critical history of modern architecture, which he has subsequently developed in other writings.

Cacciari’s interpretation begins from the idea of an uprooting of dwelling, a withdrawal of language, and the eradication of place, all of which corresponds to the negative moment in Heidegger’s analysis. For other phenomenologically inspired authors like Christian Norberg-Schulz and Kenneth Frampton, this state must be countered by a remedy, either the rediscovery of a genius loci or a rediscovery of the mediated forms of tectonics (where the reconciliation of technology and nature suggested in the first line of interpretation delineated above is never far away). For Cacciari however, the inverse is true: there is no return to an authentic dwelling, and what Heidegger asks of us is instead that we should learn to endure its absence as an irrevocable fate. Heidegger shows us the truth of modern architecture, Cacciari suggests, the impossibility of the “Values and Purposes on which this architecture nourishes itself,”15 neither a nostalgia for some remote past, nor a desire for a future harmony, but a ruthless display of the insurmountable distance from the actual condition that marks all such discourses—including that of Heidegger’s semi-mythological Fourfold and his imagery of old wooden bridge over the Rhine, which for Cacciari appear as proofs a contrario of our inescapable modernity. This is also testified to by Heidegger’s turn to poetry, which in Cacciari’s reading preserves, although in the “non-being of its word,” the lost tectonic element to which buildings can only “allude tragicomically.”16 It is true, he notes, that Heidegger oscillates between the tragic and the nostalgic mode, although in the end, following Hölderlin, tragedy must prevail, as in Mies’s “great glass windows,” which point to the “the nullity, the silence of dwelling.”17 If Heidegger shows us the truth of architecture, Mies as it were does the same in architecture.

In other works, for instance the postface to the English-language collection Architecture and Nihilism, Cacciari has developed these ideas, where he now instead cites Adolf Loos as the main example. Here he also develops an idea of “resistance,” which seems to have little or no place in the commentary on Heidegger and Mies. In Loos, the architectural project accepts its finite character, but in this, Cacciari suggests, it also opens up a “multiplicity of times that must be recognized, analyzed, and composed,” so that “no absolute may resound in this space-time,”18 not even the absolute of some utmost gathering of being’s possibilities, as in Heidegger’s analysis of technology. This, he claims, is a positive and productive nihilism that must be accounted for in acts that are continually new, which is how he sees the paradoxically positive dimension of a pure negative thought.

There is no doubt a tension here: on the one hand Cacciari wants to show nihilism as the unavoidable outcome of modernity, on the other hand he wants to see it as a plurality of languages, as in the case of Loos, which contradicts the logic of gathering and consummation derived from Heidegger. The readings of Mies’s silence developed along this line first point to the necessity of remaining within the void, within nothingness, but then to a “multiplicity of times” without an “absolute,” which seems to transform this Nothing into a set of possibilities.

Negative Dialectics

Other readings, closer to the Frankfurt School, would rather suggest that the resistance of negative thought must itself be understood as resulting from a determined social reality, as a moment of abstraction that is forced upon a subject, which must yet preserve the possibility of another relation to the world. Now, between these readings there is something like an antinomy of critical reason: on the one hand, it seems impossible to critique the present without presupposing some form of redemption or reconciliation, no matter how indeterminate; on the other hand, it seems just as impossible to presuppose any substantial redemption without giving in to an uncritically accepted metaphysical heritage. The dialectic, with its reference to a state of redemption, even if it is understood as “negative dialectics” in the sense intended by Adorno, for Cacciari would appear as a nostalgic idea, whereas the proposal of Adorno’s critical theory would be that an idea of non-dialectical resistance is simply the effect of the abstraction of late capitalism itself and ends up mimicking what it wants to resist.

This second interpretation, which draws on the Frankfurt School and the legacy of Adorno and Benjamin, will here be represented by texts by K. Michael Hays. The two essays that I will draw on here, “Critical Architecture: Between Culture and Norm” (1984), and “Odysseus and the Oarsmen, or, Mies’ Abstraction once again” (1994),19 both address the possibility of a critical architecture that would propose a resistance to the world by way of an abstraction, where it both refuses to partake in social life and, in this very refusal, shows that it is necessarily conditioned by it: architecture interiorizes the social contradictions as contradictions inside its own form, as Adorno would say. Neither simply an instrument of culture, nor a pure autonomous form, architecture has a “worldliness” that mediates the exchange between the abstraction of metropolitan life and artistic form. Discussing Mies’s skyscraper projects from the early 1920s, Hays traces this dialectic between an architectural object that is open to reflecting the world while at the same time remaining formally opaque, and that seeks to become a temporal event while still producing a distance from reality—which is even intensified in those later projects that seem to sternly refuse any participation in the fabric of urban life, and instead “open up a clearing of implacable silence in the chaos of the nervous Metropolis.”20 Similarly, in the Barcelona Pavilion, Hays perceives a space of stark juxtapositions and contradictory perceptions, endowed with a temporal extension that calls upon the bodily trajectory of the viewer while still opening a “cleft in the continuous surface of reality.”21

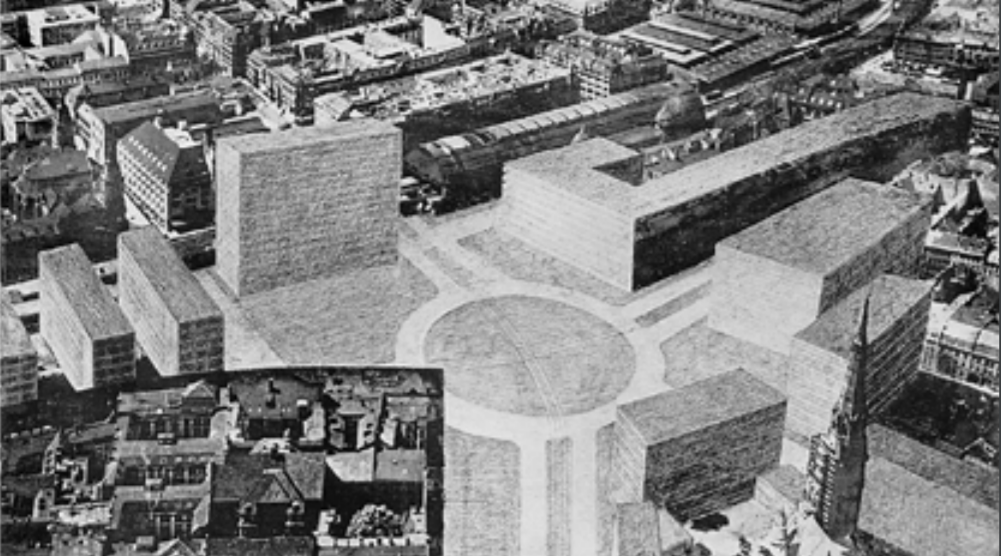

Mies van der Rohe, urban design proposal for Alexanderplatz, Berlin-Mitte, 1929. Aerial perspective view. With Photomontage (lost) originally published in Das Neue Berlin, February 1929.

The second essay focuses on Mies’s later American work and analyzes the tension between the optical dimension (glass surfaces and façade texture) and tectonic structure (steel frame), and here too Hays locates a moment of resistance, where the work both claims a presence as an intrusive object, as well as undermines the authority of aesthetic experience through the iteration of assembly line–like features. Drawing on Adorno’s distinction between construction and mimesis, Hays sees in this an impulse to “desubjectify” aesthetic experience (construction), as well as, on the other hand, a necessity to make us feel and experience this loss (mimesis), which once more leads us, in Hays’s words “to the silence, the abstraction that almost every analysis of Mies ends up declaring,”22 although not simply as a loss, but as that highest possibility of artistic language, where it allows the maximum tension between mimetic and constructive elements to be “set into a work,” to use a Heideggerian phrase.

For Hays these tensions are however not so much the final revelation of the underlying ontological condition of modernity, as in Cacciari, as a social one, which he describes in the wake of Adorno and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment and its famous analysis of Homer’s siren song, where the dialectic between the artwork’s sensuous density and plenitude, and its abstraction and dispersion, is mapped onto the structurally analogous process of abstraction in society itself. The experience of abstraction (where we have to hear the tension between these two concepts) in late modernity is materialized in the Seagram Building, it is what it says, by withdrawing into a silence that is the only way to keep the promise of another language alive. Its word, we might say (which Hays does not say), must remain “artless” in the hope of another art to which aesthetics at present can only point in a negative and oblique fashion.

Whereas Cacciari wants the negative thought that underlies his cross-reading of Mies and Heidegger to remain infinite, irrevocable, and thus in the end to be something that no longer can be understood along the lines of the Hegelian negativity that is a basic resource of critical theory, Hays insists on the idea of a determinate negation, where the autonomy of the work is always bound up with the abstraction of the commodity as a social process. The resistance of the work must be exerted with respect both to the commodity and to the idea of the work itself as purveyor of pleasure, enjoyment, etc.—all of which eventually threatens to make critical mimesis and simple surrender virtually indistinguishable, so that what Adorno called the “mimesis of the petrified,” in facts ends up itself becoming something equally petrified and petrifying. The critical operation means to make this silence speak, or to speak in place of it; it means to invent a language that would be adequate to the withdrawal of language, with all the pitfalls that this entails.

Crossing the Line

The topos of silence can be taken as a sign of a larger complex of ideas, with which the fate of what has become known as “critical theory” is entangled. As we have seen, it can be interpreted either in terms of a negative dialectic that seeks to save the particular from being subsumed under the violence of the concept (Adorno), or as a withdrawal of language that belongs to being itself in the age of technology—a figure of thought from Heidegger, which is put to use at least implicitly in Tafur and Dal Co, if we follow Cacciari’s reading. Both are figures that for a long time seemed wholly opposed, but at present appear to share many essential assumptions, above all the role of negativity, finite or infinite. To this one may oppose a third option, which understands silence, withdrawal, and negation as merely local effects, and aspires to move beyond the logic of critical negation. This is obviously a simplification: these three versions intersect in many ways, and what I here present as polemical oppositions no doubt consist of a series of small displacements; we can come back to this in the discussion.

In the two first versions, silence and negation were located in terms of an ending, which may be interpreted in different ways: as the end of metaphysics, or as the tragic final gesture of autonomous and critical art in a world of commodification—Mies’s beinahe nichts as the withdrawal of nature in the age of planetary technology, or as the final word of dialectics. But would there not be a way to pluralize such endings, to read them as points of passage and transitions, where future and past are both transformed—which also would mean to catch sight of our own present not as a belated echo, a vacuous repetition or parody, but as itself demanding an active act of interpretation?

This will entail an understanding of the relation of nihilism, art, and technology as a field of constant modulation where none of these parameters is fixed, but each moves along with history. This claim does not entail any rejection of the critical as such, but argues for its continued relevance beyond any specific models of subjectivity and experience. These concepts must in turn be subjected to a historical analysis that acknowledges and accounts for them as ongoing processes of construction.

If we look back at the reading of the Seagram building suggested by Tafuri and Dal Co, we may note that the ending that they proclaimed was in fact nothing but a beginning, as in the Chase Manhattan Building, the Union Carbide Building, and a proliferating series of further corporate high-rises. As we have seen, for Tafuri and Dal Co, this repetition follows the logic of tragic and farce proposed by Marx in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte: “What is tragic in the Seagram building is repeated as a norm in these in the form of farce.”23 The ubiquity of the curtain wall, the profusion of small plazas adorned with fountains, became defining features of corporate architecture—which, Tafuri and Dal Co somewhat hesitantly remark, it would be “wrong to consider contrary to the intentions of Mies,” just as it would be “wrong to reduce his intentions to just that.”24 If Mies draws a kind of critical line, it still proved impossible not to overstep it, and in fact, the farcical betrayal can be understood as already inscribed in the tragedy; with time, the distinction between them becomes increasingly unstable, as if the repetition would gradually insinuate itself into the tragic division itself, multiplying it in a series of echoes, producing precisely the kind of flowing modulation and image profusion that was already part of the initial modularity. Just as the iconoclastic gesture is already teeming with images, the silence proclaimed by the return of the purity of structure comes to reflect the noises of the Metropolis, as if to raise the sensory overload into an object of thought that however remains supremely undecidable.

With respect to the interpretation of Mies in particular, and the transformed technological landscape in which his later work is situated, Reinhold Martin has proposed such a reading in terms of what he calls the “organizational complex.”25 Martin takes his cues from the passages on the Seagram Building in Tafuri and Dal Co’s Modern Architecture cited above, and asks whether we should not try to understand the repetition of the Miesian forms as making possible a different type of experience, rather than as an ending. The repetition that we find in, for instance, Saarinen’s IBM project is part of a process of modulation, rather than a tragedy becoming farce.

Eero Saarinen, IBM manufacturing and training facility, 1958 Rochester, Minnesota.

From now on, architecture inhabits an essentially informatic space, and Martin proposes that we should think of it as one of several media. In this perspective it is not incidental that the kind of suspended surface that we encounter in the curtain wall emerges at the same time as network television—“the curtain wall is a medium to be watched in passing rather than looked at like an artwork.”26 These forms are not the end of something (the heroic ambitions of modernist utopias, critical architecture, reflection, etc.), but rather, Martin writes, “ciphers in which past and future are scrambled into a continuous modulated hum: an endless feedback loop.”27

In this, architecture indeed still plays an important role, although not in the sense of a resistance or an autonomous art that would take it upon itself to signify an impossible redemption. Architecture, Martin suggests, should be understood as a conduit for organizational patterns, not just an image or an ideological screen, but more fundamentally as an active force that shapes and moulds subjects. On the level of architectural history, this displaces the question of whether modernism has an end, where the initial utopian projects were eventually abandoned, betrayed, or compromised, and instead focuses on the way in which older theories and visions were reworked, taken apart, and reconfigured in order to become operative in a new complex of knowledge and power. The relation between the two historical moments, the historical avant-garde and its post-war repetition, would then not be something like a break, a betrayal or a cut, but rather a transformation, and the task of a critical theory would be to account for the multiple possibilities for action and reaction that this process contains, and not to assemble them into one unified trajectory.

Such a genealogy would show that the silence of Mies’s glass boxes, in all their stubborn negativity and renunciation of a certain architectural eloquence, in fact harbored a whole plethora of words to come, the promise or threat of new and pliant discourses that in many aspects form the very element of the world of today. The shift from the singularity of negation and withdrawal to the plurality of silences then opens up the possibility for a different communication between past and present, which prolongs some of the intuitions of earlier critical theory, but also breaks with it in certain respects.

This is inherent in the transformative reading of the avant-garde that I suggested initially: technological and social transformations are taken up in aesthetic practices that transform our self-relations. This first appears as a destruction of aesthetics in a negative sense, a mere collapse of inherited values, but then begins to take on a different sense as we look to the idea of transformation. Aesthetics neither dies nor lives on as a perpetually safeguarded zone, but is always reconstituted in relation to the other spheres of experience, which themselves are just as fluid. In this sense, “great art” (Heidegger) or “genuine aesthetic experiences” (Adorno) occurs in those events in which the concepts of aesthetics and art are transformed and opened up, so as to become spaces of possibility, or rather, spaces of virtuality, where there is also a qualitative change in our perception of the past. Such events are moments when the inherited sense of art first may have appeared to disintegrate, but in fact were undergoing a transformation that made new and unexpected artistic practices possible.

Martin stresses that the transformation of architecture in the immediate postwar period was connected to development of the discourse of cybernetics, which, we should note, also formed the backdrop for Heidegger’s perhaps slightly paranoid description of technology as ab-solute, i.e. as a systemic loop of steering and securing that absorbs all exteriorities and outsides. But instead of an absolute that gathers together all the moments of history into a final phase that absorbs subject and objects, and eventually engulfs philosophy itself, it is equally possible to understand this as the formation of other subjectivities and possibilities of experience, including aesthetic ones that take these experiential modes as their point of departure. For Heidegger, the “end of philosophy” that places us before “task of thinking”28 occurs as at this moment, just as the possibility of a genuine aesthetic experience for Adorno was transformed into a negative utopia that can only be kept alive in the utmost negation of current experience. A different reading of this moment may allow us to come back to these slightly apocalyptic gestures, to disentangle them from the perception of their own moment as the final one, and make them productive once more in our present, by stressing the moment of indeterminacy that they contain, an indeterminacy that is of the order of virtual—which is perhaps how we should understanding Cacciari’s reading of nihilism in Loos as an opening toward “multiplicity of times that must be recognize, analyzed, and composed,” as he writes in the postface to Architecture and Nihilism.

In this shift critical theory itself seems to be on the line; but what is such a line? Can we simply move beyond it, or should we assume that this line does not delimit a space that would simply extend before us and that we could simply enter into, but that it runs through ourselves?

The conclusion would be the following: we cannot simply leave critical theory behind, but neither can we simply continue to use the concepts that it has bequeathed to us. Adorno famously notes in the draft for an introduction to Aesthetic Theory that the very expression “philosophical aesthetics” gives the impression of something outdated.29 Rather than a confession of failure, this is a precise indication of the fact that all critical-theoretical reflections themselves belong to time, and must move with it, which Adorno was the first to admit, and which is one of the founding premises of his aesthetic theory. Similarly, if many of the proposals in Heidegger’s analysis of technology appear in need of a confrontation with contemporary developments, and the assumed independence of technology’s “essence” from actual technology must be questioned, such a questioning in fact belongs to the movement of thought itself, and is a sign of fidelity rather than rejection. The highly insecure status of almost infinitely saturated, dense, and overdetermined concepts like Nature and the Subject, which have functioned like the regulative ideas of critical theory, should then not lead us to despair, nor to any simplistic rejection of critique as such. If we instead assume that nature and subjectivity as the horizon against which all such concepts are understood, necessarily move together, in parallax, so to speak, then the loss or waning of certain categories should not be confused with any end of critique. The task of theory remains as important as ever, and what we earlier formulated as the antinomy of critical reason should then not be seen as heralding its end, but as the sign of a necessary transformation.

Interventions, intersections, excavations

The carrying on of a legacy can occur in many ways: through the inflection, deflection, diffraction, etc., of an interpretative canon, as was sketched out in the foregoing, but also in the way in which current works pick up themes, images, perhaps even fantasies from the past. In this sense, where and how we place Mies, as one of the decisive paradigms of a certain modernism, says a lot about where we place ourselves.

In Fritz Neumeyer’s interpretation, the Neue Nationalgalerie provides is own perspective on the cityscape; the viewing frames produce a visual immersion, especially as they appear at night in the luminosity of the Metropolis, when the building is both a translucent structure and itself a source of light. While the new extension by Herzog & de Meuron, which will undoubtedly change the perception of this interplay, will have to wait until 2026, and the thoroughgoing renovation undertaken by David Chipperfield Architects largely preserves, or, due to structural and regulatory necessities, carefully modifies outward appearances,30 in a more encompassing historical perspective the drastic changes wrought on the larger scenery of Potsdamer Platz and its surroundings are evident. Architecture’s deep involvement with time can be felt as one attempts to sense the shifts in the cityscape: once a hotspot of Berlin’s social life (of which is it difficult to imagine that it didn’t provide the architect with a texture of memories, even haunting reminiscences of a culture receding into the past as his own life was drawing to a close), then passing through a long period of postwar ruinous dilapidation intensified by the construction of the Berlin wall, and finally ushering in the current corporate and administrative cityscape that testifies to global economic power structures rather than anything connected to the history of Berlin. The viewing frames that Neumeyer highlighted are today enclosed within multiple other frames, perhaps in a sense that echoes the repetitions that were inscribed from the outset in the Seagram Building, undermining its tragic authority and opening its self-enclosed aloofness to the proliferating series of glass boxes.

Excavating the time, the temporal becoming of the building, can be taken as the focus of the two smaller projects, presented at the opening alongside the huge retrospective “Alexander Calder: Minimal/Maximal” and “The Art of Society, 1900-1945,” by Veronika Kellndorfer and Michael Wesely, both of which in their respective ways pick up the idea of the frame as a condition of viewing. Kellndorfer, present both in the Nationalgalerie and in the Mies van der Rohe-Haus with the exhibition “Screens and Sieves,” brings together works that create an overlay of inside and outside, reflections and multiple views that originate in the photographs of the emptied space as it appeared at the outset of the renovation in 2015. Collecting the traces of the process, Kellndorfer transfers them onto glass, in a “continuation of the dialectic of transparency and reflection” in Mies.31

Veronika Kellendorfer, installation view Neue Nationalgalerie, 2021

Similarly, Michael Wesely’s take on this transformation involves a marked sense of time and process. Over a period of five years, four cameras took photographs with an exposure time of two minutes, creating an atmospheric superimposition contained within the architectural frames, a dialectic of temporal fluidity and structural stability. Moving objects appear as haunting semi-presences, on the verge of disappearing in a spatiotemporal “palimpsest,” or a “presence through absence.”32

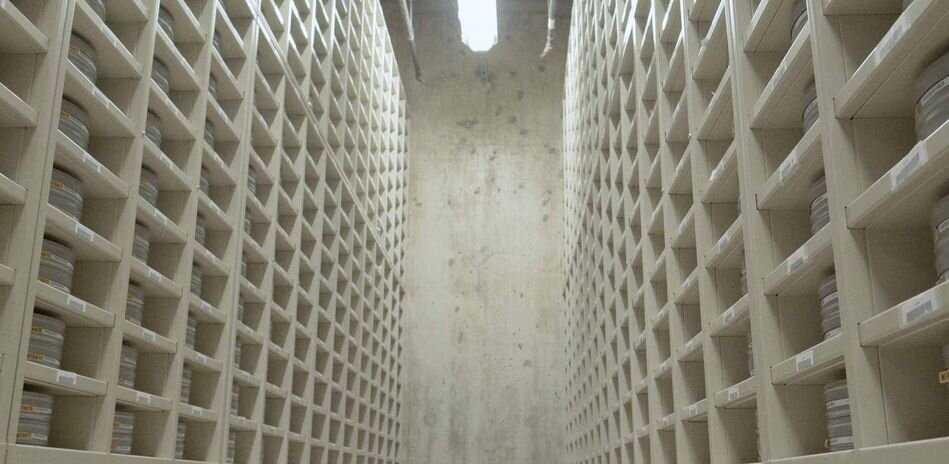

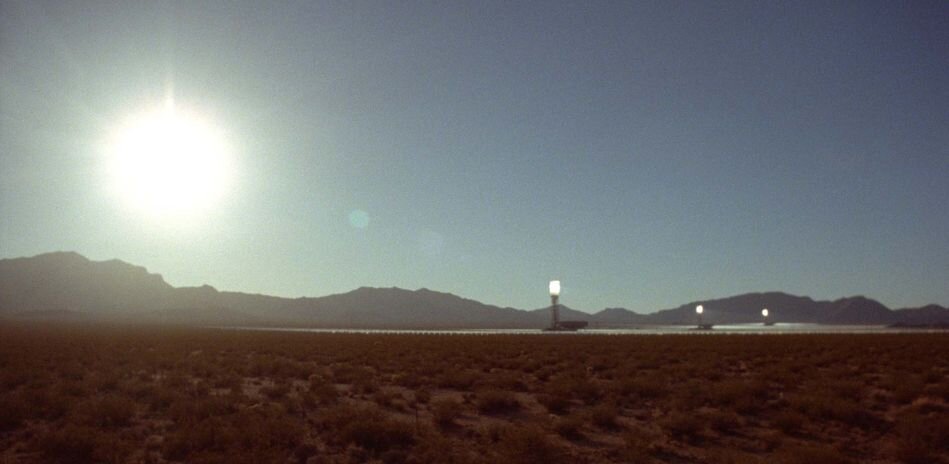

On a larger scale, Barba Rosa’s retrospective film installation “In A Perpetual Now”, too, draws on the dialectic of image. time, and frame. Referencing Mies’s early Brick Country House (1923/24)—an unrealized project now only surviving as a few charcoal drawings and a floor plan, but which was widely circulated in exhibitions and books, and played an important role in promoting the architect’s career—Rosa’s installation echoes Mies’s free-standing walls in her Blind Volume (2021) that sets up an archive of her earlier work, in the form of free-standing frames.

Installation views: Rosa Barba. In a Perpetual Now, Exhibition view, Neue Nationalgalerie, 2021 © Rosa Barba / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2021, Photo: Andrea Rossetti.

Stills: Rosa Barba, From Source to Poem, 2016, Film still, 35mm film, color, optical sound, 12 min. © Rosa Barba

Mies van der Rohe's sketch of the Brick Country House, aka Brick Country Villa. Image via "5 Projects: Interview 5 - Alex Maymind" on Archinect.

Drawing on all the technical dimensions of film (and in this appearing to carry on and extend the legacy of “structural film” from the ’60s): the camera, the lighting, the movement, the projector, the reel, the very materiality of film laid out before us as loops on the floor as the projectors operate by themselves, as in Color Studies (2013) and Boundaries of Consumption (2012), the exhibition crates a sense of circularity—a perpetual now that turns back on itself—metaphorically as well as literally. In Enigmatic Whisper (2017) we step into Alexander Calder’s old studio, thus setting up a relation to the exhibition one floor above, and the objects preserved in the artist’s workspace begin to acquire a life of their own, overlaying past and present into a deepened now. Finally, in a new work, Plastic Limits (2021), Rosa shows us the glass hall of the Neue Nationalgalerie, foggy and suffused with images of other Berlin vistas, as if amalgamating inside and outside, rendering the limit between the transparency meant to open a perspective on the cityscape, and the building’s claim to itself act as source of light, plastic, diffuse, or osmotic.

Outside of the venue of the Nationalgalerie, many other approaches appeared in the thirty exhibitions under the general rubric “Mies in Mind” scattered around Berlin at the time of the opening. In her solo show at Ester Schipper, Barba Rosa adds new afterthoughts to the exhibition at the museum, once more engaging the materiality and sculptural resources of film on a smaller scale—the main piece however being a singularly beautiful film, Inside the Outset: Evoking a Space of Passage, which, while not having any direct relation to Mies, delves even further down into the layers of the past, now deposed in the form of an ancient shipwreck, generating s similar temporal dislocation as the works in the Nationalgalerie. Jorge Pardo, whose installation Untitled in the museum café creates an atmospheric setting with light sculptures and wall panels, has a series of works on display at neugerriemschneider, which references Lilly Rich, Mies’s close collaborator in key works like the Barcelona Pavilion and the Villa Tugendhat. Pardo combines a vast array of digital visual sources that are transferred onto wooden panels, creating a dense entanglement of forms and colors.

Jorge Pardo, Untitled, 2021. © Jorge Pardo. Courtesy the artist and neugerriemschneider, Berlin

At Galerie Nordenhake too, the visual and historical legacy of the Barcelona Pavilion is at stake, in the works of Spencher Finch, Christian Andersson and Laercio Redondo. Finch pursues his long-term project to explore the underpinnings of perceptions and memory, this time with works from a 2018 site-specific installation for the pavilion, Curtain Study and Invisible Breeze, which explore the limits of what we can recall and grasp—Mies’s beinahe nichts invested with a particular tactile and palpable presence. Christian Andersson’s Angel of Hearth has a more physical attack, twisting and dismantling the Barcelona Chair into a contorted form.

Installation views from Galerie Nordenhake, Berlin with works by Christian Andersson, Spencer Finch, Laercio Redondo, and Richard Serra

Lilly Reich once more surfaces in Redondo’s sculpture, extracted from an earlier and larger project from 2020 dealing with the Barcelona Pavilion, The Simplest Thing is the Hardest to Do. Untitled (Mourning for Georg Kolbe), a replica of the plinth designed for Kolbe’s sculpture Dawn in the pavilion, with superimposed photographic images that recall the charged political aftermath of both Reich and Kolbe in the Nazi Germany, poses in its own subtle fashion how memories can be imprinted in objects of a seemingly innocuous character.

The Barcelona pavilion was also the point of departure for Maria Taniguchi, whose work at carlier gabauer, Mies 421 (2010), explores the surfaces of the building: marble and travertine, the cycle of light and visitors as they traverse the pavilion, in a loop of photographic images rhythmicized by a metronome-like beat that gives the series an increasing pace. If Finch’s curtains invite us to linger and recollect, and Pardo’s synthetic rendering of Reich’s work produce something like a virtual portrait outside of time, Taniguchi instead plunges us into time, pushing us onward with a flickering pulse that displays the inconsistent and fragmented quality of memory, and disjointing the temporal flow into so many parcels of spatial fragments of an evanescent now.

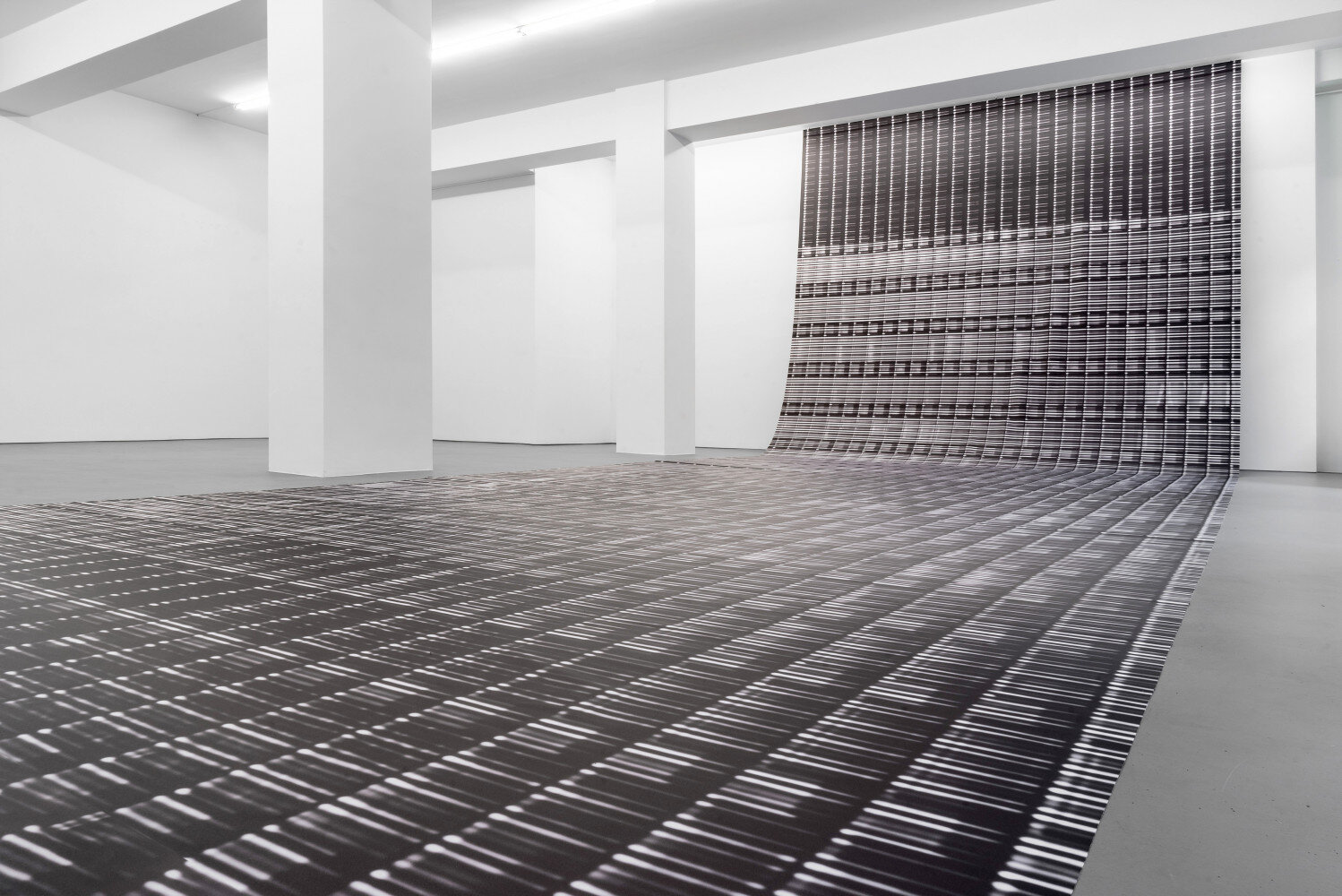

Bettina Pousttch Suspended Seagram, 2017. Installation view at Buchmann Galerie.

One of the most powerful takes on Mies was Bettina Pousttch’s Suspended Seagram, at Buchmann Galerie, first shown as part of a site-specific installation the Chicago Arts Club in 2017. A photograph of the building printed on textile that flows out on the floor (in the Buchmann Galerie not so much suspended, as in the wall mounting in Chicago, as unfolding, stretching out, and taking hold of both wall and floor), the work displaces the game of renunciation-reification-repetition played in the successive readings of Tafuri and Dal Co, Hays, and Martin. It proposes a soft and pliant structure that neither stands aloof from its surroundings nor prefigures a mediatic space of screens, but unhinges the language of slabs, girders, and frames, allowing surfaces to extend laterally, all of which most likely was not part of Mies’s intention, but then again, as time goes by, might appear as not wholly contrary to it.

Also see SITESPEAK on Mies van der Rohe below:

Image on first page: Neue NationalgalerieAußenansicht / Exterior view, 2021© BBR / Marcus Ebener / Ludwig Mies van der Rohe / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2021

1 The Silences of Mies (Stockholm: Axl Books, 2008). Available in Site Zones library.

2 For a discussion of Giedion in this perspective, see my ”Space, Power, Control,” Site Zones.

3 For a reading of Mies along these lines, see Fritz Neumeyer, “A World in Itself: Architecture and Technology,” in Detlef Mertins (ed.), The Presence of Mies (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994). See also Neumeyer’s lengthy introduction to his edition of the writings of Mies, Das kunstlose Wort: Gedanken zur Baukunst (Berlin: Siedler, 1986); trans. by Mark Jarzombek as The Artless Word: Mies van der Rohe on the Building Art (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT, 1991)

4 Neumeyer, “A World in Itself,” 72.

5 Ibid, 78.

6 Ibid, 81.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid, 83.

9 Das kunstlose Wort, 405; The Artless Word, 399. Similar claims can be found in the prewar period, for instance in the lecture “The Preconditions of Architectural Work” (1928), where Mies states: “We do not need less but more technology. We see in technology the possibility of freeing ourselves, the opportunity to help the masses. We do not need less science, but a science that is more spiritual; not less, but a more mature economic energy. All of that will only become possible when man asserts himself in objective nature and relates it to himself.” (Das kunstlose Wort, 365; The Artless Word, 301) Eric Bolle suggests that is not until the postwar period that a decisive shift occurs, as in the Farnsworth House (1950), where is technology has become entirely spiritualized; see Bolle,“Der Architekt und der Wille zur Macht: Das Problem der Technik in den Schriften von Ernst Jünger und Mies van der Rohe,” Weimarer Beiträge 38 (1992): 390-406.

10 Manfredo Tafuri and Francesco Dal Co, Modern Architecture, trans. Erich Robert Wolf (New York: Rizzoli, 1980), 2 vol.

11 Ibid, 312.

12 Ibid.

13 For a more sustained discussion, specifically of the different versions of ”ending,” see my Architecture, Critique, Ideology: Writings on Architecture and Theory (Stockholm: Axl Books, 2016), 39-55. Available in Site Zones library.

14 “Eupalinos, or Architecture,” trans. Stephen Sartarelli, in K. Michael Hays (ed.), Architecture Theory since 1968 (Cambridge, Mass: MIT, 1998).

15 Ibid, 394.

16 Ibid, 398.

17 Ibid, 404. Referencing the project for a federal court building in Chicago, Tafuri and Dal Co read the homogenous glassed expanse as a mirror, in which the “almost nothing” is transformed into a “large glass,” although not with the intricate visual and linguistic puns of Duchamp’s glass. The “reflecting images of the urban chaos that surrounds the timeless Miesian purity” accept all possible phenomena, it “absorbs them, restores them to themselves in a perverse multi-duplication, like a Pop Art sculpture that obliges the American metropolis to look at itself reflected.” (Modern Architecture, 314)

18 Cacciari, Architecture and Nihilism: On the Philosophy of Modern Architecture, trans. Stephen Sartarelli (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 203.

19 “Critical Architecture: Between Culture and Norm,” Perspecta, vol. 21 (1984); “Odysseus and the Oarsmen, or, Mies’ Abstraction once again,” in Detlef Mertins (ed.), The Presence of Mies (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994).

20 Hays, “Critical Architecture,” 22.

21 Ibid, 25.

22 Hays, “Odysseus and the Oarsmen,” 237.

23 Modern Architecture, 312.

24 Ibid.

25 Reinhold Martin, The Organizational Complex: Architecture, Media, and Corporate Space (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT, 2004).

26 Martin, The Organizational Complex, 6.

27 Ibid, 7.

28 See “Das Ende der Philosophie und die Aufgabe des Denkens,” in Heidegger, Zur Sache des Denkens (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1969).

29 Adorno, Ästhetische Theorie (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1973), 493.

30 For Chipperfield’s account of the process, including a series of acerbic remarks on the shortcomings, structural as well as functional, of the original building, see https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/aug/30/curse-mies-van-der-rohe-puddle-strewn-gallery-david-chipperfield-berlin-national

31 See Joachim Jäger’s interview with the artist: https://blog.smb.museum/durchblicke-aufsichten-reflexionen-veronika-kellndorfer-und-die-neue-nationalgalerie/

32 See Jonathan Tucker’s interview with the artist: https://www.buildingonthebuilt.org/archive-michael-wesely. This project is also published in Michael Wesely, Neue Nationalgalerie 160401–201209, with essays by Joachim Jäger, Alexander Schwarz, and Thomas Weski (Stuttgart: Hatje Cantz, 2021).