Merleau-Ponty and Sartre, Readers of Proust

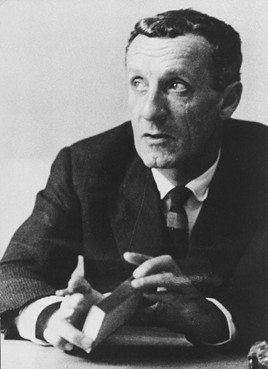

Franck Robert

Writers produce their readers.[1] Readers reciprocally produce the writers they read.

Proust wrote in In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower:

The reason for which a work of genius is not easily admired from the start is that the man who has created it is extraordinary, that few other men resemble him. It is his work itself which, by fertilizing the rare minds capable of understanding it, will make them grow and multiply. [...] What artists call posterity is the posterity of the work of art. It is essential that the work [...] shall create its own posterity.[2]

Merleau-Ponty wrote in Phenomenology of Perception:

In fact, every language conveys its own teaching and carries its meaning into the listener’s mind. A school of music or painting which is at first not understood, eventually, by its own action, creates its own public, if it really says something; that is, it does so by secreting its own meaning.[3]

Proust has built his posterity, but his posterity has also built Proust. Were Sartre and Merleau-Ponty begotten by Proust? While such an existential posterity might seem surprising, a phenomenological posterity is easier to understand. On top of this question, we can also ask which Proust have Sartre and Merleau-Ponty built?

Merleau-Ponty reads Proust differently to Sartre. Sartre often read Proust against Proust. In particular, he proposed a theory of literature against Proust’s idea of literature. Merleau-Ponty, on the contrary, read Proust with Proust. He discovered in Remembrance of Things Past a philosophy for which he had himself sought.

Furthermore, Merleau-Ponty used Proust against Sartre. Sartre’s philosophy was a constant point for discussion in Merleau-Ponty’s writings, even if this discussion was not always direct, frontal. Merleau-Ponty found in Proust’s work ideas that challenged Sartre’s ontology in Being and Nothingness.

I would like to confront these two readings of Proust.

First, it should be noted that the first reading of Proust by Merleau-Ponty, in the Phenomenology of Perception, was mediated by Sartre. Although Merleau-Ponty already criticized Sartre, he seems to share some of the Sartrean criticisms of Proust. But by the early 1950s, Merleau-Ponty read Proust more carefully, and developed his own critique of Sartre’s ontology. These two projects did not just happen at the same time, they were two parts folded into the same philosophical development of Merleau-Ponty’s thought.

Merleau-Ponty’s critique of Sartre would involve a meditation on:

1) the relationship between the subject and the world.

2) relationships with others, particularly in the case of love.

3) the meaning of literature and the commitment of the writer.

All these points are linked.

The subject and the world

In the early 1950s, Merleau-Ponty dedicated two courses to literature, Les recherches sur l'usage littéraire du langage and part of the course on Le problème de la parole. This course is partly dedicated to a precise reading of Proust’s published work.

With Proust, Merleau-Ponty criticized Sartre’s ontology of the “en soi” and the “pour soi,” of the “in-itself” and the “for-itself.” For Sartre, the real is pure “in itself,” being with no negativity, pure positivity. The for-itself is consciousness, which is nothingness. The pure “in-itself” implies a pure “for-itself,” a sheer correlation between “in itself” and “for-itself.”

According to Merleau-Ponty, Sartre did not see the intimate link between subject and world. Indeed, perception obliges us to refuse an absolute distinction between the “in itself” and “for itself.” Reading Proust, however, allows us to see in perception the intimate link between subject and world. This is a corporeal link. Merleau-Ponty wrote in Le problème de la parole: “For Proust, the pure correlation between the ‘in itself’ and the “for itself” is replaced by a lateral relation of complicity by the body.”[4] Merleau-Ponty based this thesis on the analysis of a fundamental episode: the perception of the steeples of Martinville and Vieuxvicq. Two things to note in this connection:

1) In the lecture course he delivered on speech, Merleau-Ponty comments on the episode of the steeples: after a ride in a carriage, the narrator feels the need to describe what he has just experienced, the perceptive experience of the appearance of the steeples. The body is essential to the encounter between the subject and the world: the body, as a lived body, as the center of perception and movement, founds the unity and the reality of the perceived thing. The steeples give themselves to one and the same body in their multiple profiles: the perceiving body in motion establishes the unity, in the flux of its experience, of the thing perceived. The thing perceived is always already there as a promise: it is perceived only by being there and elsewhere, only by remaining partial and inexhaustible, only a sketch of itself; the thing is only there by opening onto what it is not, by stepping over, by anticipating what it not yet.

In this sense, for Merleau-Ponty, the thing perceived appears in a way that is not foreign to fantasy: whereas Sartre opposed perception and imagination, Merleau-Ponty, along with Proust, brought them together. There is a dreamlike dimension to perception.

Another aspect of perception is emphasized by Proust and Merleau-Ponty: the perceived thing gives itself to be perceived only to a body whose movement is essential to perception itself.

Proust thus describes the primordial game of movement and sight, the game of body, thing, and world. When the narrator approaches the steeples, it is both they and he who are moving.

With Proust, and against the Sartrean ontology of the in-itself and for-itself, Merleau-Ponty underlined the sensible dimension of our relationship to the world. The world extends our body, and our body opens onto the world.

For Merleau-Ponty, Proust’s style expresses this. While Sartre rarely commented on Proust’s style, Merleau-Ponty paid particular attention to it. Images, comparisons, and above all metaphors, are not only a question of style, they have an ontological meaning, as the episode of the steeples shows. The appearance of things and the world is poetic. This is another reason why Merleau-Ponty, unlike Sartre, did not separate perception from imagination, the real from the imaginary: the appearance of things is already metaphorical. The steeples thus appear as “three golden pivots,” “painted flowers.”

2) One can find in painting a pre-conceptual expression of this metaphorical relationship to the world. The world appears poetically. In the Port of Carquethuit, painted by Elstir, the city is marine, the sea is urban. The painting expresses the encounter of the subject, in particular his body, and the world: it shows the appearance of ideas, “essences,” which emerge from the sensible. These essences are alogical. This is what the painter, Elstir, expresses and conveys. These alogical essences are also expressed in music, as Swann’s listening to Vinteuil’s little musical phrase shows. The sonata reveals to Swann the truth of his love for Odette.

Merleau-Ponty commented on this in detail. With Proust, Merleau-Ponty was able to think creative language on the basis of painting and music, not painting and music on the basis of language, since alogical essences can also be expressed by language when language translates our experience of world into words. This experience is beyond every thought of experience. It is precisely the meeting of the body and the world, a lateral relationship that constitutes their entanglement, the interlacing of things with our life.

For Merleau-Ponty, this is the meaning of autobiographical experiences for the narrator. Such experiences seem devoid of any philosophical meaning, but they are necessary to discover the essential meaning of our experience of the world. Literature must convey this experience, and the story of this expression and the expression itself can thus show the emergence of this sensible meaning, irreducible to any intellectual idea.

This critique of Sartre’s ontology implies a critique of his conception of the relationship to the other. This is the second point I would now like to examine.

Relationships with others

We may be surprised to see Merleau-Ponty criticize Sartre’s conception of the other by way of Proust’s approach on this matter. It is customary to see in Remembrance of Things Past the story of a man, the narrator, incapable of transcending himself toward others. The hero lives within himself, with himself: immanence is his world. His life seems to confirm the impossibility of love.

First, Sartre seems to be right in his interpretation of the relationship of the narrator and Albertine: Proust’s conception of love could be understood based on Sartre’s ideas of freedom. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre analyzed the failure of all love. Love is not a desire for possession. If this were the case, the hero would be satisfied when Albertine is a prisoner. But Albertine is a consciousness, and he does not possess her. He is only calm when she is sleeping. The lover wants to possess a freedom, but he cannot bear this freedom. The transcendence of the beloved makes him jealous. Sartre’s conception of consciousness implies the failure of love, itself an illusion.

Proust here serves as an example in Sartre’s examination of the limits of any relationship with the other. But he also criticizes Proust for his psychological atomism. In the Phenomenology of Perception, Merleau-Ponty agrees with Sartre. He criticizes the how psychological atomism makes us think about time and the subject in a particular way. His example is the Proustian description of love. But his reading is reductive, since it functions more as a reading of Sartre than it does of Proust. At this point, Merleau-Ponty admonishes Proust for not thinking of the subject as a global project of existence, which is temporalized in the process of life. On the contrary, analytical psychology or the novelist end up thinking of consciousness “as a multiplicity of psychic facts among which he tries to establish causal relations.”[5]

Merleau-Ponty quotes Sartre’s example: “Proust shows how Swann’s love for Odette causes the jealousy which, in turn, modifies his love, since Swann, always anxious to win her from any possible rival, really has no time to look at Odette.”[6] According to Merleau-Ponty and Sartre, this must be corrected: love and jealousy are one and the same structure of existence, one and the same way of being in the world. Time is neither a succession of temporal atoms, nor is the subject a succession of psychic facts.

But is such a critique of Proust valid? One should note that Sartre himself suggested that his reading of Proust was reductive. He conceded that Proust went beyond his own presuppositions: despite his intellectualist and analytical tendencies, he showed that love is not the desire to possess a woman. Love is a way of being in the world, a fundamental relationship of the “for itself” with the world and a relationship with itself through a particular woman.[7] Therefore, even Sartre acknowledged that Proust had done something else than what he claimed. He went beyond his own intellectualism and analytical mind.

This is precisely the meaning of Merleau-Ponty’s reading. But Merleau-Ponty offered a new analysis of love that also challenged Sartre’s philosophy of constitution. In a lecture course about institution, delivered at the Collège de France in 1953-1954, Merleau-Ponty studied the institution of love, carefully reading Proust. Love can neither be analyzed as a succession of facts linked by a causal mechanism, nor is it a decision and an illusion, as Sartre thought.

Merleau-Ponty thought of love as an institution. The narrator’s love for Albertine springs from his love for Gilberte and the Duchess of Guermantes, and it is inaugurated by his love for his mother; all loves are instituted, and a love, like Swann’s love for Odette, is the story of an institution. Love is not an illusion because it is impossible: its impossibility is rather its reality.

But what does institution mean for Merleau-Ponty? This means that the present inaugurates the future, but the future confirms and fulfils the present. For example, the love of Albertine, which is a story of anguishes, is inaugurated by the narrator’s anguish as a child. But the meaning of this inaugural moment is fulfilled by his love for Albertine. It is not, as Sartre thought, a mechanical causality. It is more complex. If the meaning of love is crystallized in the future of this love, this future is anticipated, as Albertine Gone shows. The end of love is played out during the history of love, it is anticipated. Urstiftung calls for Nachstiftung and Endsiftung, but where the end, the last event, for example Albertine’s death, fulfils the meaning of the whole love story.

Moreover, it leads to the correction of all the illusions of love. It is true, as both the narrator and Sartre thought, there is an element of illusion in love: love is subjective, love is a generality, love is imaginary. But the institution of love shows something else. Further, while also it is true that love is egocentric, love is also the idea of a life together. And, indeed, while it is true that love is imaginary, the imagination makes love real. True, love is a generality, but ultimately it is Albertine who is loved. All this shows that love is neither a decision, nor an illusion. With this analysis, Merleau-Ponty was both reading Proust and challenging Sartre’s reading of Proust and his philosophy of the constitution.

Much more, this analysis allowed Merleau-Ponty to show that Proust’s literature is not analytical, it is not a literature based in knowledge, as Sartre thought. Proust’s philosophy is neither analytical nor intellectualist. It is the “creation of speaking images”[8] – precisely what Merleau-Ponty called sensible ideas, sensible and alogical essences. The sensible ideas that literature expresses are ways of experiencing the world, of experiencing love. These manners are folds of the sensible, folds of the flesh. Swann’s love for Odette, the narrator’s love for Albertine, draw on structures of the lived world. Swann discovers the truth of love in Vinteuil’s sonata. The writer must also reveal such structures through his style.

Once again, for Merleau-Ponty, reading Proust was a way to discuss Sartre. At the same time, we can also think the opposite: it is because of his closeness to Proust that Merleau-Ponty disagrees with Sartre. In fact, Proust did not think of love as a mechanical phenomenon, a causal phenomenon. He described our experience of the world, our experience of others. He expressed it through sensible ideas, which are our ways of being in the world. Through his style the writer creates these sensible ideas, which convey the ways of being in the world, of living the phenomena.

Describing this is the main issue of literature. The writer’s task is to be committed. This is the third point I would like to examine.

What is literature?

Merleau-Ponty’s course on the problem of speech was in effect his “what is literature?”[9] It is thus a response to Sartre, though Merleau-Ponty’s ambition was quite different. While Sartre tried to think about contemporary literature, about the literature that should be the literature of his time, Merleau-Ponty questioned its ontological meaning. Modern literature, from Montaigne to Proust, has an ontological meaning. As creative speech, writing reveals the ontological power of language. Proust is the writer who made this ontological meaning the subject of his work.

a) But why is it committed writing? We can be surprised to see in this course an approach to committed literature. Sartre criticized Proust’s work because it is incapable of conveying contemporary problems: it is incapable of being the voice of the workers. More besides, Proust was Sartre’s first literary enemy in 1945 when he wrote the presentation of the review Les Temps Modernes. We have already noted the criticism of intellectualist psychology. But we must quote all of Sartre’s contention to show the grounds for the condemnation of Proust’s conception of literature.

Sartre wrote:

Such is the origin of intellectualist psychology of which the works of Proust offer us the most complete example. As a pederast, Proust thought he could draw on his homosexual experience when he wanted to depict Swann’s love for Odette; as a bourgeois, he presents this feeling of a rich and idle bourgeois for a kept woman as the prototype of love: it is therefore that he believes in the existence of universal passions whose mechanism does not vary significatly when one modifies the sexual characteristics, the social condition, the nation, or the time of the individuals who feel them. Having thus “isolated” these immutable affections, he can undertake to reduce them, in turn, to elementary particles. Faithful to the postulates of the analytical mind, he does not even imagine that there could be a dialectic of feelings, but only a mechanism. Thus, social atomism [...] leads to psychological atomism.[10]

For Sartre, writers are in a situation: their responsibility is to take a position on problems of their time. When literature is bourgeois literature, its point of view is analytical and intellectualist. It presupposes a universal human nature. But this idea of a universal human being is the negation of what men are: in particular, it is the negation of what a proletarian is. Sartre thus condemned this analytical and intellectualist literature. Proust is the writer who for Sartre symbolizes this literature, unable to see the singularity of men, and specifically of workers. For Sartre, Proust represents the bourgeois writer par excellence.

On the contrary, Merleau-Ponty saw in La Recherche a committed writing. There are two major reasons for this.

1) First, for an artist like Proust, to be committed is not to be explicitly committed politically or socially engaged. Literature does not have to describe workers to speak to workers. The theme does not make the commitment. Nor does the intended audience.[11] The writer does not have to write about workers to appeal to workers. As we have seen, he must write about man in order to reveal the structures of the lived world, which may interest any man who can also experience these structures. Proust is opposed to a theoretical literature that would serve ideas, a theory. Indeed, engagement is not a matter of decision, but of life: writers are engaged by their life. They are engaged when, living, they can access the truth of life. This life is the life of a man who speaks.

2) Second, Remembrance of Things Past is a committed work, because Proust’s fundamental commitment is a commitment to speech: it is the work of a man who is totally committed to language. A human being is a being of speech: describing how a man is engaged in speech, as Proust does in his work, reveals what it means to be human. This reveals the ontological dimension of human beings. It is thus unsurprising to see committed writing present in La Recherche. La Recherche is the story of a writer: the story of a man who writes. As a “conquering language,”[12] writing reveals the meaning of language for human beings. La Recherche is thus the story of a man committed to speech. The narrator responds to a call to speak: the experience of the world must be expressed and be expressed in its truth.

b) This is why it becomes essential to confront life and work: how is life involved in work and work in life? This may be surprising, but Merleau-Ponty studied this by considering Proust’s existentialism. When, at the beginning of the fifties, Merleau-Ponty’s research became ontological, his thought remained a discussion of existentialism. More precisely, existentialism, which questions the way for human beings to exist, leads to ontology. But we may be surprised by the fact that he would seek to analyze the ontological meaning of existentialism by studying Proust’s understanding of ideas. Certainly, Merleau-Ponty reacted to the debates of his time, but there is a deeper reason for the discussion of the ontological meaning of existentialism: truth lies in the lived world, in our sensible life.

Here it is important to note that Merleau-Ponty addressed Proust’s Platonism and his existentialism, two philosophies that constitute the front and back of the same approach to truth. As Merleau-Ponty writes:

By restoring this lived, pre-notional world, we make the transition to the idea: that is, we construct a “spiritual equivalent” of existence. Proust’s Platonism, which is the natural continuation of his “existentialism” = because Platonism does not consist in celebrating the ideas of the intelligence, but in making appear the true essences which are only found through the chiaroscuro of the lived experience, which we construct with our own life.[13]

Indeed, the hero is in search of truth, in search of the essence of things. However these essences are not separated from life and sensible experience. This research is the research into his life, and he discovered that essences are something else than what he had thought: they are not intelligible ideas, but sensible ideas, what Merleau-Ponty called “invisible.”

An example of this is Proust’s view on love. As we have seen, Sartre criticized this, specifically targeting how Proust transposed homosexual love onto heterosexual love. Merleau-Ponty on the contrary understood this decision. For Sartre, writers must be sincere,[14] but this sincerity presupposes the transparency of our life. Merleau-Ponty thought writers could be seemingly insincere. However, this is only an appearance, because when writers conceal their life, they in fact talk about themselves and us. They show ways of being that are their own and universal, but this universality is oblique. For example, when Proust wrote about the narrator’s love for Albertine, it was not a lie. Love for Albertine is without possession. It is a way of experiencing love.

Writers can then translate their own life into situations that are very different from their real life, because this translation shows the meaning of their experience. But this meaning is not only the meaning of their experience, it is a meaning that is relevant for many other situations. This outlines what Merleau-Ponty called “the syntax of the lived world.” This syntax is the structure of a life that anyone can live. This is the meaning of a lateral, oblique universality.

This syntax of the lived world is invisible, and in literature it is expressed by style, which reveals our way of living and perceiving the world. We already live and perceive according to a certain style, and literature expresses this.

It is in this sense that Merleau-Ponty really stems from Proust. This is not the case with Sartre, at least not with respect to his philosophy. Sartre’s reading of Proust was reductive and partial.[15] There is a difference between the narrator’s speech and Proust’s own actions. Sartre interpreted Proust starting from the first theses of the main protagonist, but did not see that he went further than what he had said. He forgot that writing modifies the meaning of the work. He forgot that Remembrance of Things Past is precisely research. Proust, in his work, thought more than he said. Just as there is, for Merleau-Ponty, an unthought of Husserl, there is an unthought of Proust. A thought that was not explicitly thought by Proust. This unthought is precisely the meaning of the work: how the hero and/or narrator discovers that he must abandon his initial idea of philosophy, literature, and truth. Sartre failed to see that this first idea of literature is not where Remembrance of Things Past leads the narrator, the writer, and the reader. There is obviously a Proustian psychology, Merleau-Ponty conceded: subjectivity of love, disappointment of the world and love. But this psychology does not reveal the truth of love and the world.

Merleau-Ponty writes:

The theme of Past and Lost Time is generalized [...]. The themes of Proustian “psychology” (subjectivity of love, disappointment of the world and love) also appear as a very partial aspect of his work. One says (Sartre) analytical psychology, intellectualist, inner mechanisms. This is the surface: these are the psychological “laws” that Proust was talking about. This is the “knowledge literature” element. But the knowledge of subjectivity and mechanisms is only a preface to Proust’s own theme, which is the passage to the idea through the act of creative expression.[16]

There is no intelligible essence of love, and Proust did not establish a law of love, he described people as “a crystallization of an essence.”[17] That is, the essence embodies itself in the person. There is also no essence of subjectivity, there is more a subjectivity who lives truth, and a truth which emerges from all experiences of love.

Merleau-Ponty continues:

Subjectivity is not Proust’s last word: it also means that in the subject, there is everything, it is the aspect under which the essence of the narrator is announced, of which we can make universal truth. – Literature for Proust is essentially this passage to the universal by deciphering lived experience.[18]

One can see in Proust’s work something similar to the passage from the natural attitude to the transcendental attitude in phenomenology, a transcendental attitude that never forgets its own impurity, its natural origin. Time regained discovers the truth of experience when experience seems incapable of revealing the truth. The truth of experience is set in life when life is expressed through art. Proust’s authentic commitment is located there: through his work, which recounts the passage from experience to expression and to truth, he assumes that man is a speaking being.

c) But is that a decision? At the end of his course, Merleau-Ponty asks if we can explain the theory and practice of literature by an existential choice.[19] Merleau-Ponty discusses Sartre’s conception of freedom and his voluntarism. He confronted this conception with the condition of the writer, and Proust in particular.

Unfortunately, Merleau-Ponty did not distinguish between Proust, on the one hand, and the narrator and his story, on the other. He talked about Proust, but his reference was most often the story of the hero. Even if the writer and the hero are only partially the same, they share the same sensibility. This sensibility precedes his choice. This sensibility is a certain way of receiving the world: he discovers that things both contain and hide something. The experience of the steeples of Martinville shows it.

Thus, there is a choice, Merleau-Ponty said, only if one considers an absolute freedom at the origin of this sensibility itself, as Sartre thought. The Proustian sensibility would then be a choice. We know that Merleau-Ponty elsewhere tried to grasp a passivity of activity, and that he refused the idea of an absolute choice. But he also refused to speak of a fatum. He preferred to speak of a slope. He preferred to speak of a way of life, of a modality of existence, to explain Proust’s decision to write. It is not an absolute decision, a pure choice, but instead is the expression of this modality of existence.

But there are no psychological structures that would belong specifically to Proust: the predominance of the past, the feeling of unreality, pansubjectivism, and relativism, are not structures of Proust’s psyche, they are, according to Merleau-Ponty, universal structures. This is why Merleau-Ponty refused to explain the work by an existential choice in the way Sartre did. The choice is not what explains the work. The choice is taken from an experience that is not only Proust’s experience, but an experience that everyone – every writer and human being – could live. Reciprocally, Merleau-Ponty wrote, the work to be undertaken implies such a choice. There is thus a dialectical relationship between life and the work.

From the case of Proust, Merleau-Ponty then went on to discuss Sartre’s idea of existential psychoanalysis.[20] Sartre had not yet written L’Idiot de la famille (1971-1972) on Flaubert, but he had written Baudelaire (1946) and St Genet, écrivain et martyr (1952). Merleau-Ponty had discussed the thesis of Being and Nothingness on existential psychoanalysis: for Sartre, we can understand the totality of a human being from his original project, for which an existential choice could explain the work. Choice is primitive. But for Merleau-Ponty, the absolute freedom that Sartre attributed to the human being is already freedom in front of others, and therefore is not absolute. Proust’s choice is Proust’s choice for Sartre, even when Sartre understood it as an absolute choice.

Merleau-Ponty did not oppose Sartre and Proust: both are right, both have their reasons. It is true that a writer can only express what he lives, but this has a universal value. This universal value is however not already given at the beginning: there is no universal nature that the writer could express. Universality is at the end: it is the result of an exchange, it is brought about by reading and emerges from the relationship with others. This is what Remembrance of Things Past shows. Existence is not simply closed on itself. It is not only solitude, for it calls for expression. Existence speaks. As existence, it is solitude; as speaking existence, it is open to others and to a universal meaning. This is the discrepancy of the writer, a discrepancy present in every human being. Remembrance of Things Past is the story of this discrepancy. From his solitude, the writer writes for others. He opens himself to others.

Merleau-Ponty concludes:

The expression germinates of itself in the disorder of life and returns to life through all those with whom the writer communicates. The writer is not simply a man who writes, he is off-center, but in that very sense, he is a human being.[21]

Conclusion

We are now reading Proust together. By reading Proust, we read Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, and others who have also read Proust. Proust, like the narrator, his hero, is also a reader. We compose a speaking community, and we find in literature, in Remembrance of Things Past par excellence, a syntax of the lived world that we also experience. Proust wrote that the reader is not a reader of his book, he is a reader of himself: in his reading, he discovers himself, his own life, the truth of his life and of life.

For Merleau-Ponty, this is Proust’s real commitment: his commitment is a commitment to speech, and speech is what every man is engaged in. Remembrance of Things Past is the story of this commitment. This commitment is then a commitment to the truth. Such a commitment thus has a philosophical meaning. But this meaning does not precede life and work. Sartre criticized the bourgeois literature of Proust, which would consider a human nature. However, what Sartre did not see was that, through his work, Proust had discovered something else: rather than unveiling intellectual essences, Proust expressed, through his style, the emergence of truth within the sensible experience; he expressed sensible ideas, the invisible.

While phenomenology tries to break away from the natural attitude and settles in the transcendental attitude, Proust shows how truth and essences emerge from our lived experiences, from our own errors, in particular our philosophical beliefs and errors. Sartre did not see this journey, which never forgets its own failure, its own impurity, and which calls for an incessant renewal. Just as the writer at the end of Time regained understands that he must write his book, we understand that we have to read Remembrance of Things Past and all other literary work again and again; we have to start again and again to philosophize, read, and speak. This is due to our belonging to a universal community of language that, in no small art, is constructed through literature.

I would like to thank Lovisa Andén and Sven-Olov Wallenstein for inviting me to present this lecture at the symposium “Proust och filosofin” at Södertörn University, December 9, 2023. I also thank Chloé Beccaria for her help in preparing this text in English.

Franck Robert teaches philosophy at Lycée André Honnorat, Barcelonnette. Among his recent publications: Phénoménologie et ontologie (2005); Merleau-Ponty, Whitehead, le procès sensible (2011), and Merleau-Ponty, Sur le problème de la parole (2020; co-ed. with Emmanuel de Saint Aubert and Lovisa Andén).

[1] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phénoménologie de la perception (Paris: Gallimard, 1945/1976), 209. À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs (Paris: Gallimard/Pléiade, 1988), I:522.

[2] À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs, ibid: “Ce qui est cause qu’une œuvre de génie est difficilement admirée tout de suite, c’est que celui qui l’a écrite est extraordinaire, que peu de gens lui ressemblent. C’est son œuvre elle-même qui en fécondant les rares esprits capables de la comprendre, les fera croître et multiplier. [...] Ce qu’on appelle la postérité, c’est la postérité de l’œuvre. Il faut que l’œuvre [...] crée elle-même sa postérité.”

[3] Phénoménologie de la perception, 209: “Tout langage en somme s’enseigne lui-même et importe son sens dans l’esprit de l’auditeur. Une musique ou une peinture qui n’est d’abord pas comprise finit par se créer elle-même son public, si vraiment elle dit quelque chose, c’est-à-dire par sécréter elle-même sa signification.”

[4] Le problème de la parole: Cours au Collège de France: Notes, 1953-1954, édition établie et annotée par Lovisa Andén, Franck Robert, Emmanuel de Saint Aubert (Geneva: MētisPresses, 2020), 163: “Pour Proust, la corrélation pure en soi-pour soi est remplacée par un rapport latéral de complicité par le corps.”

[5] Phénoménologie de la perception, 486: “comme une multiplicité de faits psychiques entre lesquels il essaie d’établir des rapports de causalité.”

[6] Ibid, “Proust montre comment l’amour de Swann pou Odette entraîne la jalousie qui, à son tour, modifie l’amour, puisque Swann, toujours soucieux de l’enlever de tout autre, perd le loisir de contempler Odette.”

[7] Jean-Paul Sartre, L’Être et le Néant (Paris: Gallimard, 1943/1976), 622.

[8] Le poblème de la parole, 172: “création d’images parlantes.”

[9] Ibid, 173, 178.

[10] Sartre, “Présentation des Temps Modernes,” Les Temps Modernes, no. 1, October 1, 1945, reprinted in Situations II (Paris: Gallimard, 1948), 19: “Telle est l’origine de la psychologie intellectualiste dont les œuvres de Proust nous offrent l’exemple le plus achevé. Pédéraste, Proust a cru pouvoir s’aider de son expérience homosexuelle lorsqu’il a voulu dépeindre l’amour de Swann pour Odette; bourgeois, il présente ce sentiment d’un bourgeois riche et oisif pour une femme entretenue comme le prototype de l’amour: c’est donc qu’il croit à l’existence de passions universelles dont le mécanisme ne varie pas sensiblement quand on modifie les caractères sexuels, la condition sociale, la nation ou l’époque des individus qui les ressentent. Après avoir ainsi ‘isolé’ ces affections immuables, il pourra entreprendre de les réduire, à leur tour, à des particules élémentaires. Fidèle aux postulats de l’esprit d’analyse, il n’imagine même pas qu’il puisse y avoir une dialectique des sentiments, mais seulement un mécanisme. Ainsi l’atomisme social […] entraîne l’atomisme psychologique.”

[11] Le problème de la parole, 176.

[12] Ibid, 210: “parole conquérante.”

[13] Ibid, 178-179: “En restituant ce monde vécu, pré-notionnel, on effectue le passage à l’id: i. e. on construit un ‘équivalent spirituel’ de l’existence. Platonisme de Proust qui est la suite naturelle de son ‘existentialisme’ = parce que le platonisme ne consiste pas à célébrer les idées de l’intelligence, mais à faire apparaître les vraies essences qui ne se trouvent qu’à travers le clair-obscur du vécu, que nous construisons avec notre propre vie.”

[14] Ibid,177, 185.

[15] Ibid, 179.

[16] Ibid, 179: “Le thème du Passé et du Temps Perdu se généralise: ‘Rien qu’un moment du passé ? Beaucoup plus peut-être ; quelque chose qui, commun au passé et au présent, est beaucoup plus essentiel qu’eux deux’ (TR2 14). Les thèmes de la « psychologie » proustienne (subjectivité de l’amour, déception du monde et de l’amour) apparaissent aussi comme aspect très partiel de son œuvre. On dit (Sartre) psychologie analytique, intellectualiste, des mécanismes intérieurs. C’est la surface : ce sont les « lois » psychologiques dont parlait Proust. C’est l’élément « littérature de connaissance ». Mais la connaissance de la subjectivité et des mécanismes n’est qu’une préface au thème propre de Proust qui est le passage à l’idée par l’acte d’expression créatrice.”

[17] Ibid, 179: “la cristallisation d’une essence.”

[18] Ibid, 180: “La subjectivité, ce n’est pas le dernier mot de Proust: elle veut dire aussi que dans le sujet, il y a tout, elle est l’aspect sous lequel s’annonce l’essence du narrateur, dont on peut faire vérité universelle. - La littérature pour Proust est essentiellement ce passage à l’universel par déchiffrement du vécu.”

[19] Ibid, 195-196

[20] Ibid, 97.

[21] Ibid, 198: “l’expression germe d’elle-même dans le désordre de la vie et retourne à la vie à travers tous ceux avec qui l’écrivain communique. L’écrivain n’est pas simplement un homme qui écrit, il est décentré, mais en cela même il est homme.”